| Date: | 12/18/2020 |

|---|---|

| Organization: | Office of the Inspector General |

| Referenced Sources: | OIG Finds Self-Dealing and Pay Discrepancies by Former Director of Hingham Housing Authority and Poor Oversight by HHA Board |

- This page, OIG Letter to Hingham Housing Authority Regarding Its Former Executive Director, Sharon Napier, is offered by

- Office of the Inspector General

Letter OIG Letter to Hingham Housing Authority Regarding Its Former Executive Director, Sharon Napier

Contact for OIG Letter to Hingham Housing Authority Regarding Its Former Executive Director, Sharon Napier

Fraud Hotline - Office of the Inspector General

Phone

Online

Table of Contents

Re: Hingham Housing Authority and its Former Executive Director, Sharon Napier

December 4, 2020

By Email

Ms. Janine Suchecki, Chair

Hingham Housing Authority

30 Thaxter Street

Hingham, MA 02043

Dear Ms. Suchecki:

The Office of the Inspector General (“OIG”) reviewed actions by Sharon Napier, the former Executive Director of the Hingham Housing Authority (“HHA”), and the HHA Board. The OIG found that Ms. Napier promoted her interests over HHA’s by continuing to hire a vendor with whom she had a personal and financial relationship. The OIG also found inconsistencies in the documentation she submitted for $3,551.20 in “special pay,” which resulted in her paycheck being $2,496.94 higher than normal for the same week that she paid a $2,500 fine to the State Ethics Commission.

In addition, the OIG found that the HHA Board improperly paid for Ms. Napier’s personal attorney fees in connection with an investigation by the State Ethics Commission. Finally, the OIG found that the former HHA Board’s inattention to its obligations during Ms. Napier’s tenure resulted in poor governance and insufficient oversight. The OIG’s findings and recommendations are discussed in more detail below.

The OIG commends the HHA Board for its recent efforts to improve the management at HHA and increase its oversight of the housing authority’s operations. The OIG makes several recommendations to assist the HHA Board as it moves forward.

Background

HHA is a public entity that administers 92 units of state public housing, 14 units of Chapter 689 housing1 and 25 units of federal Section 8 housing. Prior to December 2019, HHA had four employees: an executive director, two maintenance employees and an administrative employee. The executive director reports to the Board, which is composed of five members.

The membership of the Board has changed in the past two years, with two new Board members joining in the spring of 2019. HHA is funded by the state Department of Housing and Community Development (“DHCD”) and the federal Department of Housing and Urban Development (“HUD”). As such, HHA is subject to various regulations, guidelines and requirements from DHCD and HUD.

Sharon Napier became the executive director of the Hingham Housing Authority in December 2011. From 2007 through 2011, Ms. Napier worked for DHCD. Prior to that, she worked for the Falmouth Housing Authority. At its November 12, 2019 meeting, the HHA Board removed Ms. Napier from her position and entered into a management agreement with the Quincy Housing Authority to oversee HHA’s day-to-day operations.

As you are aware, the State Ethics Commission also investigated allegations of wrongdoing by Ms. Napier and in May 2019, Ms. Napier agreed to pay a $2,500 fine pursuant to a disposition agreement with the Commission.2

Finding 1

Ms. Napier promoted her interests over HHA’s by hiring a vendor with whom she had a personal and financial relationship. Further, Ms. Napier did not conduct a procurement for the vendor’s services.

In March 2006, Ms. Napier incorporated Housing Inspectional Services (“HIS”) with Patrick Rossetti, with whom she lives. That same month, they opened a business checking account for HIS with two signatories: Ms. Napier and Mr. Rossetti. Ms. Napier told the OIG that she divested herself from HIS when she began working at DHCD in 2007. However, Ms. Napier remained a signatory on the bank account until February 2018, after the State Ethics Commission began investigating her connections to HIS.

Also in 2006, HHA hired HIS to conduct inspections for its apartment units, as required by state and federal law. The contract consisted of a one-page document, signed by the then-executive director on November 9, 2006. According to Ms. Napier, the HHA Board approved the contract when it was signed.

When Ms. Napier joined HHA in 2011, she continued to use HIS to perform inspections. During Ms. Napier’s time at HHA, the housing authority paid HIS nearly $43,000, ranging between $5,000 and $6,800 per year. This accounted for about 10% of HIS’s business.3 During the same period, Mr. Rossetti wrote a total of $94,950 in monthly checks from HIS to “cash,” which Ms. Napier deposited in her personal checking account just prior to paying the mortgage for the home they shared. These checks varied between $900 and $1,000 per month when they lived in a condominium – about 60% of the mortgage payment – and increased to $2,300 per month in December 2016 when they moved into a newly constructed house – slightly more than 100% of the mortgage payment.

As HHA’s executive director, Ms. Napier never conducted a procurement for inspection services. Instead, she continued using the one-page contract with HIS from 2006. On September 21, 2018, Ms. Napier provided the OIG with a purported “procurement file” for inspection services that contained:

- An email dated July 24, 2017 from an Ohio-based inspection company stating that it could not serve Hingham

- A letter dated February 7, 2016 from a Hingham-based inspection company listing the services they provide, but not containing price quotes

- Three recommendations dated in August and September 2018 from other HIS customers

- A printout of statewide contracts dated “September – October 2018” that did not include anything relevant to inspection services

Based on these records, it is clear that Ms. Napier did not conduct a procurement.

The failure to conduct a procurement violated HHA’s procurement obligations. HHA is required to follow the state procurement law, M.G.L. c. 30B (“Chapter 30B”). Under Chapter 30B, if HHA procured inspectional services annually, Ms. Napier would have been required to use “sound business practices” for procurements costing less than $10,000, specifically “ensuring the receipt of a favorable price by periodically soliciting price lists or quotes.”4 If HHA procured inspectional services under a multi-year contract, they would have been required to solicit written price quotes or get sealed bids, depending on the length and cost of the multi-year contract. However, Ms. Napier followed neither of these processes.

Ms. Napier’s decision to retain HIS is problematic in two ways. First, Ms. Napier’s failure to conduct a procurement ensured that HHA continued to hire HIS, the business that paid most or all of the mortgage on her home. Although Ms. Napier was no longer an officer of HIS or involved in its operations, she financially relied on the business’s continued success. As such, Ms. Napier’s actions as executive director protected her own financial interests over HHA’s. For the same reason, her oversight of HIS’s work was problematic. Because Ms. Napier had a financial interest in ensuring that HIS got paid, she should not have had any role in overseeing HIS’s work, including approving payments to HIS. This conduct reflected poor management practices at HHA; it also was inconsistent with the state’s conflict of interest law,5 as well as the DHCD’s code of conduct for local housing authorities.6

Second, as discussed above, Ms. Napier did not follow state procurement law or DHCD guidelines for securing inspection services. This both violated state law and failed to ensure that HHA was getting best value for these services. Unless the HHA Board specifically voted to allow HIS’s contract to last longer than three years, Chapter 30B required Ms. Napier to conduct a procurement, at a minimum, when she arrived at HHA in 2011 and at least twice more during her tenure.

Finding 2

The HHA Board should not have paid the legal bills Ms. Napier incurred as a direct result of her breach of duties to HHA.

In December 2016, the Massachusetts State Ethics Commission initiated an investigation of Ms. Napier for potential violations of the state’s conflict of interest laws. On December 21, 2017, the Commission concluded its inquiry and found reasonable cause to believe that Ms. Napier violated Sections 20 and 23(b)(3) of Chapter 268A of the General Laws.7

On January 16, 2018, prior to that evening’s HHA Board meeting, Ms. Napier contacted the Chair of the HHA Board and requested that the Board vote to indemnify her in connection with the investigation. Ms. Napier represented to the Chair that she had spoken to the Massachusetts chapter of the National Association of Housing and Redevelopment Organizations (“MassNAHRO”), which gave her guidance that it was appropriate for HHA to indemnify her.

Although it was not on the agenda for the January 16 Board meeting, the minutes show that the Board voted 4-0 to indemnify Ms. Napier for expenses arising from the investigation. Specifically, they state:

Chair Cooper discussed MGL Chapter 258 Claims and Indemnity Procedure for the Commonwealth and its Municipalities, Counties and Districts and the Officers and Employees Thereof, Section 9: Indemnity of public employees. Keyes made motion to indemnify Director Napier as outlined in the statute, Watson seconded Resolution 2018-2A.

Vote 4-0

The Board cited the Massachusetts Tort Claims Act (“MTCA”), M.G.L. c. 258, § 9, as the basis for indemnification. Section 9 of the MTCA provides:

Public employers may indemnify public employees . . . from personal financial loss, all damages and expenses, including legal fees and costs, if any, in an amount not to exceed $1,000,000 arising out of any claim, action, award, compromise, settlement or judgment by reason of an intentional tort, or by reason of any act or omission which constitutes a violation of the civil rights of any person under any federal or state law, if such employee or official or holder of office under the constitution at the time of such intentional tort or such act or omission was acting within the scope of his official duties or employment.

Ms. Napier retained Mintz, Levin, Cohn, Ferris, Glovsky and Popeo, P.C. (“Mintz”), a large, international law firm in Boston, to represent her in the Ethics Commission’s investigation. HHA had no prior relationship with Mintz. HHA sent a $5,000 retainer payment to Mintz on February 5, 2018, and ultimately paid Mintz $10,704.75 on Ms. Napier’s behalf. The Board did not question whom Ms. Napier hired or inquire why she needed a firm that charged an hourly rate of $750 to represent her.

The Board should not have indemnified Ms. Napier. First, it is not clear that Section 9 of the MTCA authorized the Board to indemnify Ms. Napier for legal fees arising from her violations of the state’s conflict of interest law. Ms. Napier entered into a “disposition agreement” with the State Ethics Commission after the Commission completed an “inquiry.”8 That agreement constitutes a “consented-to final order” enforceable in the Superior Court.9 The words “inquiry,” “ethics violation,” “disposition agreement” and “consented-to final order” do not appear anywhere in the MTCA.10

When faced with the question of whether a town was required to indemnify a public employee under Section 13 of the MTCA, the Supreme Judicial Court (“SJC”) found that Section 13 did not authorize the town to reimburse its public employee for costs incurred in defending against ethics charges.11 The SJC so found because under the MTCA, an ethics “charge” is not a “claim” in any ordinary sense of the word and the MTCA uses the word “judgment” to refer to a final judgment in a civil lawsuit, and not to a criminal or ethics proceeding.12 There is no reason to believe that the SJC would find that the words “action, award, compromise, [and] settlement” as used in Section 9 include State Ethics Commission proceedings and orders.13

The SJC’s findings are based on a case where a public employee asked a town to pay legal fees for ethics charges that were dismissed, but did not ask for reimbursement for ethics charges that the employee admitted to. By contrast, Ms. Napier sought for HHA to pay legal fees for ethics charges for which she ultimately signed a disposition agreement stating that she agreed that she violated the conflict of interest law. The SJC stated in its opinion that, “it would be repugnant to require municipalities to pay for the legal fees of those found guilty of . . . ethics violations in connection with their official duties.”14

Second, courts will not adopt a construction of a statute “if the consequences of doing so are ‘absurd or unreasonable,’ such that it could not be what the Legislature intended.”15 The conflict of interest law generally seeks to prevent conflicts between the private interests of public employees and their public duties.16 A public employee who violates the conflict of interest law has breached their duty to the public and their employer.17

Finally, the conflict of interest law establishes various penalties for violations, including fines and, in some instances, sentences to state prison. The Legislature established these penalties to deter public employees from violating the law. When a public employer indemnifies a public employee from the consequences of violating the conflict of interest law, the Legislature’s intent is frustrated. As a result, interpreting Section 9 to permit public employers to indemnify public employees for costs associated with violating the conflict of interest law is likely “absurd” and “unreasonable” because it could not be what the Legislature intended.18 The Board should have declined to pay for Ms. Napier’s legal fees arising from her violations of the conflict of interest law.

Finding 3

Ms. Napier’s received almost $2,500 in “special pay” the same week that she paid the State Ethics Commission a $2,500 fine.

As you know, the State Ethics Commission fined Ms. Napier $2,500 because it found that she did not properly disclose her relationship with HIS. Ms. Napier paid that fine by a cashier’s check she purchased on May 14, 2018.

Although the HHA Board voted to indemnify Ms. Napier, both she and Board members told the OIG that HHA only paid her legal fees, not the $2,500 fine. However, Ms. Napier’s May 18, 2018 paycheck included $3,551.20 in “special pay,” resulting in her net pay being $2,496.94 higher than normal. The timing of and paperwork concerning this payment raise questions about its legitimacy.

According to HHA records, the $3,551.20 in “special pay” was an “admin payout” for 96.5 hours that Ms. Napier worked on a DHCD-funded project between May 8, 2016 and April 7, 2018.

In May 2016, DHCD approved a $143,721 budget for a boiler replacement project, including line items for an engineer to design the specifications for the project, a contractor to perform the work, permits from the town of Hingham and $10,100 for “other administrative expenses.” HHA hired and paid vendors to complete this project and then submitted to DHCD to get reimbursed.

Because Ms. Napier worked for HHA part-time, she was eligible to work additional hours to oversee the boiler replacement project and submit that time to DHCD for reimbursement. Any such time would be reimbursed out of the $10,100 line item for “other administrative costs.”

DHCD guidelines for capital projects required HHA to “keep timesheets for additional hours worked on the modernization project.” The guidelines further required HHA to “bill monthly for those hours, including timesheets as back up.”19

According to DHCD records, construction was completed in October 2017. On March 26, 2018, Ms. Napier submitted a request for payment to DHCD for final costs, including the entire $10,100 “other administrative costs” line item.20 Then, at its May 8, 2018 meeting, the HHA Board approved a resolution to use the $10,100 from DHCD to pay its employees the “admin payout” for additional hours they purportedly worked to administer the boiler project: $3,551.20 to Ms. Napier for 96.5 hours and either $500 or $250 to each of HHA’s three other employees. The minutes contain no explanation for how the other employees’ payout amounts were calculated.

The timing and process for this “special pay” raises questions about its legitimacy; it appears to have been a mechanism to reimburse Ms. Napier for the $2,500 fine she paid to the State Ethics Commission the same week.21 First, as noted above, HHA was supposed to bill DHCD monthly for additional hours it paid to its employees to administer the project. The monthly submissions would have reimbursed HHA for the hours it paid its employees through their regular paychecks over the past month. Instead, six months after the project ended, Ms. Napier requested $10,100 be paid to HHA for administrative costs.

Six weeks later – the same week she paid her fine – she asked the HHA Board to pay her $3,551.20 for two years’ worth of additional hours (specifically, 96.5 hours), which she purportedly had been uncompensated for up to that point. It is unclear why these payments were made in a lump sum at the end of a two-year project, rather than paid contemporaneously through the usual payroll process and then submitted to DHCD on a monthly basis for reimbursement to HHA, as DHCD’s guidelines require.

Moreover, the documentation supporting Ms. Napier’s 96.5 additional hours is not detailed enough to verify Ms. Napier’s time and contains several concerning discrepancies. Specifically, Ms. Napier provided the OIG with a series of timesheets on which she recorded hours she allegedly worked on the boiler project. These timesheets were separate from her regular timesheets.

While these timesheets record how many hours she allegedly worked each day on the boiler project, they do not specify when Ms. Napier worked those hours. In addition, on several days, Ms. Napier reported working on the boiler project on her regular timesheet, raising questions about whether she claimed the same work hours on both her regular timesheet and her boiler-project timesheets, resulting in a double payment for those hours. Had the Board regularly tracked her time on this project, it could have verified compliance with DHCD rules and ensured that Ms. Napier was accurately tracking her regular work hours and administrative time for the project.

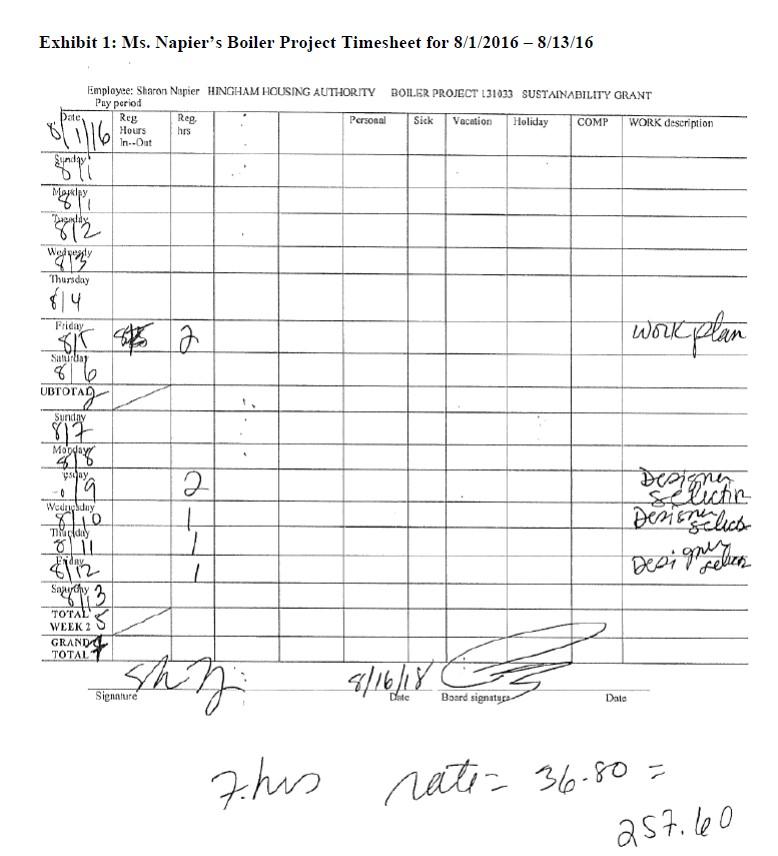

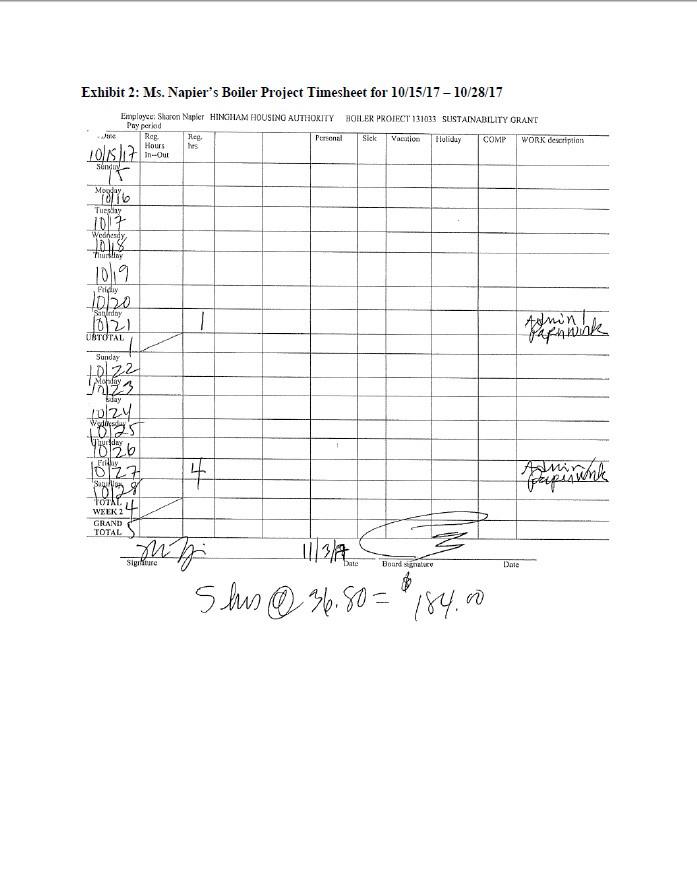

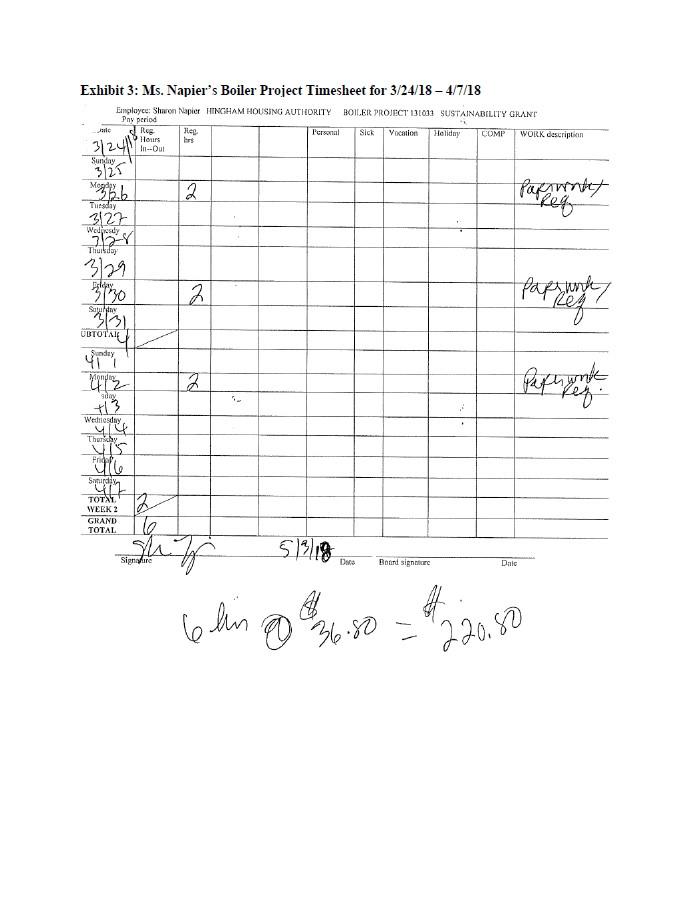

Further discrepancies on these forms raise additional questions. For example, the boiler-project timesheet for August 1, 2016 through August 13, 2016 is signed and dated “8/16/18” (see Exhibit 1). Additionally, the timesheet for October 15, 2017 through October 28, 2017 is dated “11/3/17” with the “7” in the year clearly written over an “8” (see Exhibit 2). The timesheet for March 24, 2018 through April 7, 2018 is dated on “5/3/18” with the “8” written thickly over what appears to be a “7” (see Exhibit 3).

The fact that three different boiler-plate timesheets have the year incorrectly recorded casts doubts about the timing of the creation of the documents. The now-former Board member who signed these timesheets also failed to date them. It is therefore impossible to tell whether these documents were created when Ms. Napier purportedly worked the time, or in 2018 when Ms. Napier requested the payout from the HHA Board.

In summary, the back-up documentation for Ms. Napier’s “special pay” does not contain enough detail to verify that she did or did not work those hours. Even if Ms. Napier worked all of those 96.5 additional hours, the process HHA used to pay her was improper. She should have been paid contemporaneously, and HHA should have sought DHCD reimbursement monthly. This would have allowed the Board to more effectively oversee her time and ensure it was properly documented.

Finding 4

The HHA Board did not oversee Ms. Napier’s time and attendance, raising questions about the amount of her retirement payout.

As the executive director, Ms. Napier was responsible for approving timesheets for all employees, including herself. Ms. Napier was the only person to sign off on her timesheets, and she was solely responsible for submitting time and attendance information – such as hours worked and leave taken – to HHA’s payroll vendor. In other words, the HHA Board did not take an active role in overseeing Ms. Napier’s time and attendance, including her use of leave time.

When Ms. Napier retired in January 2020, her final paycheck included $13,758.41 in “accrual pay” for unused vacation, sick and personal leave time. Ms. Napier conducted the calculations to determine how much this payout would be and submitted it to the payroll company without getting approval from the HHA Board.

Because the HHA Board did not oversee Ms. Napier’s time during her employment, it was dependent on the records that she kept of her use of sick, vacation and other leave time. The Board had no ability to verify the amount of time that Ms. Napier had accrued because it did not monitor her use of leave time. Moreover, the HHA Board’s lack of oversight of the payroll process allowed Ms. Napier to give herself this payout without the Board approving it. This made HHA vulnerable to fraud and unable to effectively serve as stewards of public funds.

Finding 5

The former HHA Board neglected its oversight duties during Ms. Napier’s tenure.

Throughout Ms. Napier’s tenure, the Board failed to fulfill its duty to oversee the operations of HHA and its employees, including Ms. Napier. The OIG’s investigation found that Board members were unaware of their essential obligations and fiduciary duties. These shortcomings created a serious vulnerability for fraud, waste and misuse of public funds and resources.

During Ms. Napier’s tenure, there was much turnover on the HHA Board, with the exception of two long-time Board members. Current and former HHA Board members told the OIG that Board meetings were disorganized, failed to stay on schedule and included very little scrutiny of the reports Ms. Napier provided to them.

When the OIG spoke with Board members, they often did not know basic information about the operations of HHA or their obligations as Board members. For example, the former treasurer of the Board told the OIG that HHA did not pay for Ms. Napier’s cell phone when in fact it did. Another Board member told the OIG that she saw no potential conflict with Ms. Napier hiring HIS even though she acknowledged the money that HHA paid HIS constituted part of Ms. Napier’s household income. Board members also described conversations at Board meetings that were not reflected in the minutes, in possible violation of the state’s open meeting laws.

In addition, the Board improperly ceded its authority to pre-approve significant spending decisions. It permitted the treasurer to sign checks without prior authorization of the Board. Instead, the Board reviewed and approved expenses after the money was expended. As noted above, the HHA Board also did not exercise any oversight of Ms. Napier’s time and attendance, including her timesheets. Relatedly, in May 2018 the Board approved a questionable payment for “additional hours” Ms. Napier purportedly had worked in 2016 and 2017. This lack of oversight increased HHA’s risk for fraud, waste and misuse of public funds.

Over the past two years, the HHA Board has seen several new members join, shifting the culture of the Board to be more proactive and better organized than it was in the past. The HHA Board began questioning Ms. Napier towards the end of her tenure, and has shown itself to be more active and engaged in its oversight responsibilities and fiduciary duties.

Conclusion and Recommendations

As HHA transitions to a management agreement with the Quincy Housing Authority and a new, more involved Board, the HHA Board has an opportunity to redesign and refocus its governance structures and operations in a way that will promote ethical leadership, good governance and accountability.

As HHA works to move forward, the OIG recommends that the HHA Board members attend the OIG’s Boards and Commissions training. The class covers topics essential to good governance, including fiduciary responsibilities and effective oversight. The OIG also recommends that the HHA Board take this opportunity to review its policies and procedures and consider the following changes:

- Review the warrant process for approving payments to ensure that the Board is overseeing and approving payments before they are made.

- Review the payroll process to ensure that the HHA Board is overseeing the executive director’s time and attendance, including overtime and leave time.

- Review policies regarding capital projects to ensure sufficient controls over administrative costs, including overtime by the executive director.

- Ensure that documentation for DHCD capital projects is sufficiently detailed to confirm that time that will be reimbursed through DHCD is documented on the regular timesheet, paid contemporaneously and reimbursed from DHCD to HHA on a monthly basis.

- Ensure that all board members complete DHCD’s mandatory training for all housing authority board members.

- Review the OIG’s educational materials for public board members, including the OIG’s free training for members of public boards and commissions.

- Ensure that HHA staff are trained in procurement and contracting laws, guidelines and best practices.

- Ensure that all staff and Board members take annual State Ethics Commission training on the conflict of interest laws and that they comply with their obligations to disclose potential conflicts of interest.

The OIG thanks the current HHA Board for its cooperation during this investigation.

Sincerely,

Glenn A. Cunha

Inspector General

Attachments (3)

cc: Tom Mayo, Hingham Town Administrator (with attachments, by email)

Jennifer Maddox, Undersecretary, Department of Housing and Community Development (with attachments, by email)