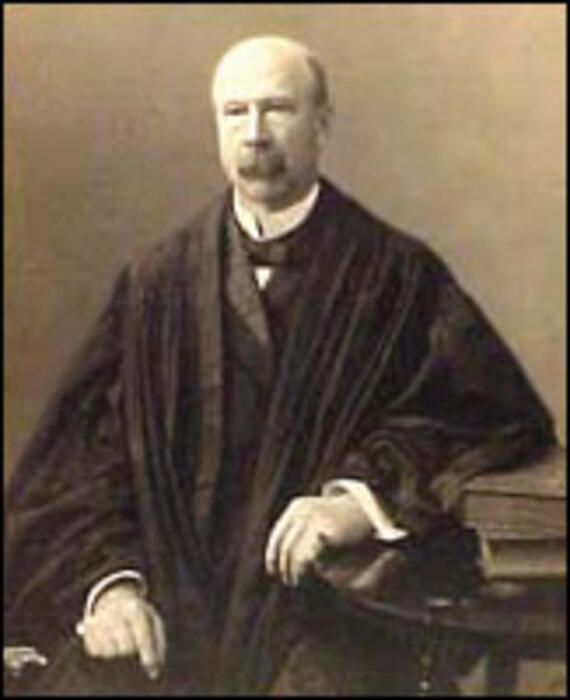

Henry King Braley

Associate Justice memorial

275 Mass. 586 (1931)

The Honorable Henry King Braley, an Associate Justice of this court from December 24, 1902, died, while still a member of the court, on January 17, 1929. On May 23, 1931, a special sitting of the full court was held at Boston, where there were the following proceedings. The Attorney General addressed the court as follows:

May it please your Honors: In behalf of the bar associations of Boston and of Fall River, I have the honor to present their tribute memorializing the life, character and service of Henry K. Braley, late Associate Justice of this Honorable Court.

Henry King Braley: A MEMORIAL.

Henry King Braley was born March 17, 1850, in Rochester, Massachusetts.

His ancestors were among the early settlers of New England, men and women of sterling character and resolute purpose.

Owing to the death of his father, Samuel Tripp Braley, he was obliged to assume responsibilities unusual to youth, in the care of his mother and younger brother. In doing this he was taught early in the school of experience to meet and courageously face problems that, successfully conquered, brought to him the self reliance and independence which were the foundation of his future success.

In 1875 he married Caroline W. Leach of Bridgewater, who was a direct descendant of Robert Cushman, one of those known so well as the Pilgrim Fathers.

Of a studious disposition, ambitious to acquire knowledge, after leaving the common school he became a student in the Rochester Academy, and later was a graduate of Pierce Academy at Middleboro. He was, for a time, a school teacher in Bridgewater. But having chosen the practice of law as his profession, to equip himself for it he became a student in the law office of Latham & Kingman, and afterward of Hosea Kingman, in Bridgewater.

He was admitted to the bar at Plymouth on the seventh of October, 1873, as a member of the firm of Hathaway Braley. Mr. Hathaway was a well known lawyer and a considerable practice was already established. This firm was later dissolved, Mr. Braley becoming the associate of Marcus G. B. Swift in the firm known as Braley & Swift. The reputation of the firm grew apace until Mr. Braley's indomitable energy and ability had won for him a high reputation. His quick perception of the interest of clients, his wisdom in advice and promptness in action secured their confidence and through them the confidence of the community. A man of such mould was needed. The City Council made him their legal adviser as City Solicitor. The people made him their Chief Executive. Business interests, corporate and private, called him into their service in positions of trust. Governor Russell in 1891 selected him as a fitting member of the Superior Court. His ready mastery and clear statement of facts made him an unerring guide to jurors in passing upon the questions which they were to decide.

That same mastery of facts was of equal service to him, in the prompt application of rules of law. His diligent study of legal precedents had enabled him to make quick decisions. In maintaining the decorum of the court room he kept in the minds of everyone the dignity befitting his own high ideal of the administration of justice. To him the law was not so much a jealous mistress as a revered sovereign. He brought to the performance of his duties in this trial court a diversified experience with men and affairs, in both private and public life.

His record there won for him promotion to the Supreme Judicial Court by appointment of Governor Crane in 1902, the highest honor in the gift of a Governor of Massachusetts.

Though Justice Braley believed that the stability of the law was best assured by an allegiance to precedent, he recognized also the value of using its elasticity to broaden its application to meet the growing requirements of justice. For this reason his contribution to judicial opinion carried the greater weight.

He was singularly able to keep an open, not a wavering, mind, but one that was free to substitute the better for the worse reasoning. No former statement of opinion -- his own or others' -- held him as its slave.

A sincere tribute to Justice Braley cannot be adequate without reference to his noble character. Nor do the Governors of this Commonwealth fail to appreciate the importance of the part that character plays in the maintenance of the splendid history of our Supreme Judicial Court.

However formal, possibly austere in demeanor Justice Braley may have seemed to be on first acquaintance, it was no cloak put on for any given time or purpose. He was born with it. Every member of the bar who came to know him realized that behind this demeanor there was a warm-hearted, sympathetic, generous man with an interest in others and desire to be helpful to them. His one fixed rule for living was to make the best use of every moment.

In his death there was lost to the people of this State a servant who had long occupied a seat in this, its highest tribunal -- the record of whose doings has been their greatest pride. He was one whose simple life, high ideals, unflinching courage, unwavering devotion to the cause of justice contributed a full share to the maintenance of law and order and of the highest standards of human conduct.

I move that this memorial may be embodied in the permanent records of this Honorable Court.

James F. Jackson, Esquire, then addressed the court as follows:

May it please your Honors: In seconding the motion that the Memorial just read be placed upon the record of this court, my mind turns from the judge to the intimate friend of a lifetime.

It so happened that Mr. Braley and I as young men both chose Fall River as the place where we would open offices for the practice of the law. He preceded me by about two years. When I arrived I found him already established at the further end of the corridor in a building known as the Pocasset Block.

Soon after my name had appeared on the door of my one room of modest dimensions and scant furniture, I met Mr. Braley. I was impressed at once with the feeling that he was going to prove an excellent example in what strict attention to business would require. And it was not long before I had occasion to know that this first impression was correct.

My somewhat irregular habit in reaching the office in the morning and my more regular habit of leaving it in the early afternoon had evidently been observed by that watchful but friendly eye. However that may be we met casually one day and, speaking of the profession, Mr. Braley said as we walked along together "A young man to succeed in the law must devote himself to it, particularly in the matter of always being found in his office during business hours." It was good advice. I knew it was, and eventually followed it.

It was quite the custom in the smaller cities and towns in those days for a community to show its respect for a lawyer by giving him the title of Squire. In due season I heard people speaking of Squire Braley. I knew it meant that he had now become known as a safe and sound adviser, and was on his way to success. It was not long before he had won a reputation upon which he was appointed a Judge of the Superior Court.

A separation in our pathways prevented us from meeting one another for several years, but we again became neighbors in Brookline.

That formality in the demeanor of Justice Braley was accompanied by what was far more important in describing the man, an imperturbable composure. In the court room it gave power to his intent glance, brief words, quick decision. It was with him in his home, in the common experiences of ordinary life. An incident illustrates it.

For many years it was my delight in summer vacation to cruise along the coast in a small yawl with Simeon Borden so well known as Clerk of Courts for Bristol County. One afternoon while sailing from Newport to Nantucket we put into Edgartown. The next morning we called upon Justice Braley at his summer home and found that an associate Justice was his guest. The day was bright and inviting, and I suggested that they go out in the afternoon for a sail. The invitation was accepted. In the harbor the wind was light and the water disturbed only by a ripple. When we got into the sound the tide and wind were stronger and the sea rougher, so that the boat in beating careened somewhat upon one and the other tack. Suddenly Justice Braley, who was sitting on the windward side with his guest, stood up and with steady step crossed to the lee rail where he sat for two or three minutes facing seaward. He then arose and returned to his former seat. Thereupon his guest said: "Well, Judge, now that you have established the precedent, I think I will follow it," and so speaking he crossed to the lee rail. No word was spoken, but I observed at their reunion a twinkle in the eyes of each as they exchanged glances. I nodded to the skipper and we put back into the harbor.

Judge Braley always seemed to have one fixed rule of living, that every waking hour had its best possible use. It was a rule that he never suspended. He appreciated the value of recreation, the value of relaxation, but he never let either of them pass the boundary and become self indulgence. He loved friendship, enjoyed to the uttermost his hours of social comradeship, his walks with friends, his evenings with them at the whist table, at the club, in every place of social companionship. He enjoyed to the uttermost all the opportunities which life opened.

While many of his friends travelled into far lands and returned with memories and pictures of scenes, in knowledge of peoples that were invaluable to them, Judge Braley sitting in his library journeyed into far countries among other peoples, into the lives of great men and returned from them with a rich store of knowledge of history, philosophy, science, of judicial sayings, judicial pronouncements that gave him the fund of incident and quotation always at his command.

Hospitable, generous to a fault, sympathetic with every call for need whether at his door or elsewhere, he gave without stint and without ostentation. We need men of that kind. Men whose success has a background of self control, self education, consistent devotion to high ideals, men who make practices out of their beliefs, self denial out of desire. We have many such men. We need more, particularly in these days, when precept is so lenient, example so all important.

My last talk with him was about ten days before he died. I found him very weak, his voice low but distinct. As I was going he said: "I have made all my business arrangements, and yesterday sent for Doctor Hale and adjusted matters of spiritual interest. I am ready to go." The same man -- the same exactness of speech we know so well; and back of it, thought and feeling that was not expressed because of his sensitive reserve. May I try to express them?

Though I can feel life's ebbing tide,

Moving out to the unknown sea,

Calm at the mooring I may ride,

Waiting the word that sets me free.

To sail alone? With God on high

With faith to chart the course so clear,

What need to question or to fear?

Herbert Parker, Esquire, then addressed the court as follows:

May it please your Honors: Our review of a life of near four score years, even to its end, radiant with the light of an ever ripening wisdom, charity, benevolence, and exalted ideals of public service, is one of gladsome and inspiring reflection, scarcely shadowed by the imperceptible transition from our associations of sight and speech, to living memories, real, as they are also imperishable.

Again, in this place, we sit in his very presence; listen again to his words of high authority; note the grave, yet gracious, bearing of a revered magistrate; in this scene of the crowning achievements of his ceaseless devotion to judicial duties committed to his charge, by the mandate of the Commonwealth.

His was the demeanor of a dignity becoming to the austerity with which the law stills, by its decrees, the complaints or controversies between clamorous adversaries. Before him, and by his very presence, an inquiry into the truth of conflicting claims, urged by contradictory, and often irreconcilable testimony, was tried in the penetrating light of a vision that suffered no falsehood to escape detection.

A long succession of opinions of the Full Court, written by Mr. Justice Braley, will for all time bear evidence, in trial test in Court, and under the laboratory analysis of the modern schools of law, of his wide learning, of his piercing discernment and of his elucidation, of the elemental and lasting, rather than the instant or ephemeral issues of any case at bar before him.

Highly and justly honored, he will always be, for his contributions to the jurisprudence of this Commonwealth and of the common law. Yet, to many of us, of the older generation, his most eminent place is with the greatest of his predecessors, as presiding magistrate in the nisi prius Court, that great clearing house of facts, where living issues have their first presentment, and whence, only living issues should survive.

The training of his youth and of his professional years, gave him a distinctive genius, always evident, for his quest for the truth, the first requirement of a trial judge. His was the schooling of early responsibility, rather than that of books, or of exposition of pedagogues.

Not for his own advantage, did he strive through those laborious days of his boyhood, but for the welfare of his own kindred, as later he wrought in high places of authority for the honor of his city, and the welfare of the State. None can better know, through any other life experience than his, the true motives, ambitions, gratifications, or disappointments, through which men come to high fortune, or stumble, or fall, in the life struggle; as competitive and destructive among those who dwell within the modest homes of a rural community, as in the wider affairs of the greater world.

His scholastic training was only that, excellent as it was, of the academies of rural Rochester, and of the Pierce Academy of Middleboro. These studies, brief as they were, stimulated his inherent love of learning, naturally leading him to the study of the law, for which his instinctive exactitude of inquiry, precision of conclusion, and of expression, furnished an admirable equipment which never failed him. He learned the elemental principles of the common law, the application, and controlling modification of statutory enactments, and he followed the lines of interpretation of both through the recorded adjudications of the courts. He learned, in the offices of honorable and famous practitioners, what no law school can teach, the trial value of the testimony of interested witnesses or parties. He learned the tests of veracity, through actual intimate observations of human conduct, at its best, and often at its worst. He learned upon what courses of proof the truth of a cause must be established. So trained, he came to the Bar, at once attaining a success which his attainments and his character assured. The impact of his perfectly prepared cases in the conflicts of the court room, shattered every defence save that which was founded in impregnable truth, and on sure principles of law. Earnestness, obvious sincerity, discreet and honorable strategy, rather than brilliancy or spectacular display, won him victories in verdicts, and in rescripts, still treasured and animate part of the history, and traditions, of the Bristol and Plymouth Bars.

He knew the needs, forecast, and framed, sound policies of administration, essential to the development of the maritime and industrial city of Fall River. By his direction, as legal advisor, and later as its chief magistrate, he gave that city its famous place in the annals of New England shipping, and of New England manufacture.

Familiar, as he was, from his youth upward, with conditions of town affairs, with the genius of the town meeting, and also with the circumstance of more complex municipal life, in industry, and finance, and knowing citizens of town and city with equal intimacy and sympathy, he knew the temperament, the sentiment, the prejudices, the frailties, and, above all, the underlying virtues of jurymen, called to the service of justice. He taught them to realize their high responsibilities. He dignified their service, and elevated their thought to a high sense of their duty, through his own manifest respect for their participation in the functions of the law. We can remember no one of our great trial judges, whose charges to jurors were more enlightened, more inspiring, than his, in large part, because of his evident confidence in their conscientious effort to find, and declare the truth in the case before them. He found few occasions, we remember none, to rebuke, or discharge a jury, for any conscious betrayal of their trust. They implicitly trusted the court, and honored his trust in them. He traced, for their guidance, the tangled threads of the truth, without color of prejudice in their pattern. He directed, with scrupulous regard for the limited boundaries of his judicial functions, the course of trial procedure, to the end that the vital issues between the litigants should be actually transmitted upon the record to the court of review. The facts under his exposition, were, with rarest exception, found by juries in accordance with the truth. From his hand, the real case, as submitted by counsel, and tried before him, passed, on appeal or exception, to the full court.

It may be said that the attributes of Mr. Justice Braley, which we have recounted, are only those which any great judge should possess. We who have known him need only to tell others who have not had that happiness that, apart from, yet part of, the judicial life we here review, were those qualities, both of mind and of heart, that endeared him to his associates in every field of his professional and public service, endeared him to the people who entrusted their causes to his guidance, to the litigants, who invoked and obeyed the decrees which he pronounced.

After his elevation to the bench, he retained a vivid, constant and observant interest in public affairs, and discharged, with punctilious fidelity, his every civic and political duty.

He was warm hearted, loving his fellows always more than himself. He was kindly, courteous, friendly and of good cheer, in all his intercourse with his friends by his fireside, and even with strangers passing along the way-sides of life. He loved good books and animated their pages by his own diffusion of their learning and their humanities.

He loved the sea, and the bland sea breezes that drift in summer time over the moors of that fair island where he found the home of his recreation. The recurrent seasons, the waves of the ocean, the inexorable sweep of the tides, the revolving stars, spoke to him always of the immutable order of the universe, and of the all wise guidance of a Divine Will. The perfect order of his own thought, his reverent obedience to every dictate of that order which he read in the skies themselves, his love of justice, his love of his fellows, made him teacher and friend, rather than by his lawful authority, ruler of the men of his times.

James M. Morton, Esquire, then addressed the court as follows:

May it please your Honors: Justice Braley was appointed to the bench three years before I was admitted to the bar, so I only knew him as a judge and as a family friend. The Braleys were originally a Quaker family. The Justice's ancestor moved from the island of Rhode Island to Freetown when he bought a share in the Pocasset purchase towards the end of the seventeenth century. They had left the Meeting long before the Justice was born and were a very typical family of southern New England farmers and mariners. The Justice's father, studied for the ministry but was lured away by the sea with its ageless call to adventure and romance. He became a whaling captain and died on voyage at Mahé one of the Seychelles Islands in the Indian Ocean.

Seamen could not spend much time at home; and the work of bringing up the family fell largely on the captain's wife. The Justice -- who was not a disinterested critic -- thought her a very remarkable woman. She not only looked after the children, but also ran the farm on which they depended for most of their living. The future judge was born while his father was at sea; and when the news reached the captain the event was duly entered in the log-book. In due time the boy was sent to school in his home town. It is an interesting fact that his teacher there, Mrs. Cornelia Rounsville Church, is still living, and in good health at the age of ninety-seven; she was present at the exercises two weeks ago at the unveiling of a tablet in the Town Hall in Rochester to the memory of her distinguished pupil. From Rochester schools young Braley went to the Pierce Academy in Middleboro, expecting to go to college. He was there when word came of his father's death. The captain left but a small estate; and his passing threw on Henry who was then twenty years old the burden of looking after the family. He kept on with his schooling until he finished the course at the Academy. It may be doubted whether anybody anywhere ever worked harder than he did at that time. He did his farm work in the morning, then walked about five miles to the railroad, and took the train to Middleboro. After school he took the train back, walked home, and finished the day's work on the farm.

After leaving the Academy, he taught school for a time, studying law while so doing. He was admitted to the Bar at Plymouth in 1873 and began practice at Fall River in the fall of that year. By 1875 he found himself in a position to marry which speaks well for the financial rewards of the profession in Fall River in those days. His wife was Miss Caroline W. Leach and their marriage was an ideally happy union. No small part of Mr. Braley's personal and professional success was due to his wife's character, aid, and affection. The young folks lived happily on $1,200 a year at first out of which they helped take care of his mother and sent his younger brother through school and the Institute of Technology. It tells a good deal about Mr. Braley that when he was about thirty he was selected by a non-partisan, good-government group in Fall River as their candidate for mayor and was twice elected to that office which he filled with much ability.

In his professional work he went rapidly ahead. His first partnership with Mr. Nicholas Hathaway was succeeded by one with Mr. M. B. B. Swift, and the firm Braley & Swift was a leading one in Fall River. As a lawyer, Mr. Braley was shrewd, resourceful, and capable, with a keen sense of the business aspects of the matter in hand. His qualities appealed strongly to business men of the active and aggressive type and he developed a large practice among them. If ever a man was headed for distinguished success at the bar Mr. Braley was. At forty-one he turned his back on it and accepted a place on the Superior Court. Why did he do it? It was a real renunciation. Perhaps there was some touch of Quaker mysticism that prompted him. We do not know.

As a trial judge he made a very great success. He was clear, capable and firm. He knew law, dealt shrewdly and strongly with questions of fact, and he understood his fellow-men better than most of us. His excellent work as a trial judge led to his promotion to this court in 1902. Other speakers are more competent to discuss his work here. It seems to me that his great quality was practical sense, an ability to keep close to the facts. While he was capable of abstract and learned discussion of pure law he seldom allowed himself to be drawn into it. His weather eye, as his father would have said, was always on the case before him. He was not a fluent writer -- such men seldom are. They are the wheel-horses of the car of Justice by whose effort, often unrecognized, it moves on from one generation to the next.

I remember one thing he did which ought to be referred to. Along with Justice Sheldon and Justice Fessenden they revamped the equity practice of the Superior Court and they did such an extremely good job that when, a few years ago, the Supreme Court of the United States was authorized to revamp the equity practice of the Federal Courts of the United States it followed very closely, so closely in fact, the equity practice which those three men set up here, that Massachusetts lawyers notice no difference.

Personally he had the precise, rather formal manners of the generation which had preceded him. Beneath that external shell there was, as has been said, a kindly, sympathetic, generous man. In the court room, Justice Braley was a martinet; nobody took liberties with him. He was constantly helping people some of whom had but slight claim upon him. In spite of his superficial precision and formalism he was a pleasant companion; his talk was serious, but not heavy, often lightened by a touch of humor. He had a keen sense of absurdities -- rather a Yankee trait.

The quality which most of his friends think of first was his untiring industry. He could say with Nietzsche: "Do I then strive after happiness? I strive after my work." His philosophy was, I think, the old and simple belief that life is a trust which we are bound to use in the best way within our knowledge; and he lived up to it far better than most of us.

Emerson once said that an institution is but the lengthened shadow of a man. It is a saying which applies to our great public institutions like this historic court. Behind the justices of the day are the shadows of those who have preceded them, of Shaw with his marvelous practical wisdom and his deep knowledge of the people whose magistrate he was; of Gray with his great book knowledge of the law; of Field with his quick and brilliant mind, and of many, many others. Their work remains, their personalities endure, we live in their lengthened shadows.

Frederick W. Mansfield, Esquire, then addressed the court as follows:

May it please your Honors: An ancient philosopher has said: Four things belong to a judge -- to hear courteously, to answer wisely, to consider soberly and to decide impartially.

Judge Braley possessed each of these qualities. His mind was so active and his legal intelligence so keen and comprehensive that if at times his manner was quick and possibly curt, yet he was always courteous, and he answered wisely when it was his duty to answer.

And in cases of more than superficial difficulty which did not admit of instant decisions he considered soberly all of the clashing elements developed by the conflict of rights and interests.

And it is unnecessary to say that his decisions were impartial, for he possessed to a remarkable degree what Burke has called "the cold neutrality of the impartial judge." But this does not mean that he was cold to litigants or lawyers. He was a kindly man.

A judge is an important man in any community, whether he be a judge in a district court where, it has been said, greater opportunities are given to judges to come in contact with the people, or whether he be a judge in the Superior Court which has often been described as the great trial court of the Commonwealth, or whether he be a judge in the Supreme Judicial Court where the people have their last resort.

Judge Braley was distinguished upon the bench in our Superior Court and those of us who remember the remarkable celerity and despatch with which he and the late Judge Sheldon disposed of business in the First Equity Division of that court have a very keen and lively realization of his remarkable nimbleness of mind and a certain legal mental dexterity which was not a mere superficial veneer but was the visible mark of a very profound legal knowledge.

It is always difficult to find apt words adequate to describe the distinguished qualities of learned and important men who have held high place in the community and who have passed to their reward. A fulsome eulogy is not convincing or satisfying and is repugnant to good sense. To choose only one of the many fine qualities possessed by Judge Braley, I think perhaps the most prominent as his love of personal liberty and his alertness to see that no citizen of the commonwealth however humble his position should be deprived of his liberty without the sanction of the law. He was ever zealous to safeguard the rights of individuals and when sitting as a single justice in the Supreme Judicial Court his work upon habeas corpus petitions stands out and will always mark him as a champion of the liberties of the ordinary man. And yet he was always bound by the law. He always acted within the law. A chief justice of this Honorable Court more than a century ago remarked in one of his opinions, "It is dangerous to attempt being wiser than the law." 1 This is something that Judge Braley never attempted. He never attempted to be wiser than the law.

"Merit and good works is the end of man's motion," said Bacon, "and conscience of the same is the accomplishment of man's rest; for if a man can be partaker of God's theatre, he shall likewise be partaker of God's rest."

Judge Braley has been a partaker of God's theatre and has played well his part. He is now a partaker of God's rest.

Felix Rackemann, Esquire, then addressed the court as follows:

May it please your Honors: The present is an impressive occasion. The Court has paused in its judicial labor, the Bar has laid aside its active work, its pleas and briefs, and many other workers in our driving and restless world have laid down their tools, all in the middle of a busy working day and all attending this sitting of the Court with a common impulse and a common feeling. What does such action signify?

The man in whose memory we come is departed. His ears no longer hear, his eyes are closed in their last eternal sleep. Nothing which we can here do or say can reach him now. All this we know, and yet we meet and speak and from this memorial service we should go with deeper impressions made upon our own lives and characters by reflections from the life we have lost.

This sitting of the Court -- this spontaneous gathering of the Bar and others -- as a small tribute to the memory, is not merely because of Mr. Justice Braley's long service upon the Bench of the Commonwealth, nor because of his legal ability, his intellectual attainment or his indefatigable industry. Something beside those items is the mainspring.

I submit to the Court that occasions of this kind are inspired only by our recognition of and compelling admiration for character. Mere intellectual power and industry, even though molded into great works, do not make to us the same challenge. And it is a good omen that we do respond to the example and challenge of "character" as such.

It was that in the deceased which brings us here, and I believe it would have brought us just the same had Justice Braley served a shorter term and with less distinguished ability.

His innate modesty would have forbidden the claim of any great pre-eminence as a jurist, or any profundity as a philosopher of law. But he could not conceal those marked characteristics as a human being which stamped his life, influenced and guided all his actions and made him the trusted upright judge that he was.

It has been wisely and truly said, as to every matter and every action in life, that between what a man knows and what a man does, there intervenes his character. It was manifestly so with Judge Braley. His inborn and controlling sense of justice never failed him, but, on the other hand, tempered and influenced his every order and decision.

He would have agreed with the late Justice James D. Colt, who once said he would like written on his tombstone: "Here lies a lawyer who never did a 'smart thing.'"

None quicker than he to sense any move or attempt savoring of trickery, sharp practice or fraud; none readier than he to give patient and attentive ear to all presentments and arguments properly advanced and germane to the subject considered; none more thoroughly conscientious in endeavor to do right; none actuated by higher motives; none moved by a higher sense of duty as a Judge and as a citizen.

Throughout his career as a public servant, Mayor and Judge, he gave, without let or, stint, of the best that was his to give.

Lincoln once said: "Biographies, as generally written, are not only misleading but false. The author makes a wonderful hero of his subject. He magnifies his perfections, if he has any, and suppresses his imperfections. History is not history unless it is the truth."

Judge Braley's obituary is written in our memories. No need to over praise. In his case, the simple truth is enough. It is enough to say of him: A devoted husband; a good father; a fine citizen; an upright, listening and learned Judge; a Christian gentleman, has passed on.

Scripture says that "With what judgments ye judge, ye shall be judged." Justice Braley may well be judged by his own judgments.

Charles Thornton Davis, Esquire, then addressed the court as follows:

May it please your Honors: Mr. Justice Braley was essentially a humanitarian. The passions, prejudices, weaknesses and virtues, all of the emotions that sway the conduct of men, were to him of intense interest. He was widely read in history, biography and moral philosophy. In poetry he turned from the school of nature to that of human passions. Above all, the needs of humanity appealed to him. Service to his fellowmen was his simple creed, and to that he gave all he had of brain, heart and strength. His interest in the law lay, not in its processes, its intellectual reasoning or its machinery, but in its effect in governing and developing human relations.

He had a shrewd knowledge of men and great common sense; he was intolerant of cowardice and chicanery; he was impatient of inefficiency; but he had a keen sense of humor and an understanding discernment of the weaknesses and limitations of human nature, and at the same time a firm and idealistic belief in its inherent roundness and capacity for development and progress. His code of ethics and of conduct was the stern code of the Puritan, but he differentiated, with rare sympathy, between sin and the sinner.

I first encountered Judge Braley shortly after his appointment to the Superior Court, when I tried a case before him that resulted in a very objectionable bill of exceptions. My learned opponent was a man, as Judge Braley told me afterwards, who had been admitted to the bar in middle life after a business experience, but without college or law school training or any material length of study in a law office. He lacked professional background and experience in the trial of cases.

Judge Braley assigned the case for a hearing on the bill of exceptions at his house in Fall River on a Saturday at half past twelve. When we arrived he stated that owing to the unusual hour he was asking us to lunch with him. During luncheon he told many reminiscences about the bar, especially about the Bristol Bar, of which my opponent was a member, and then adjourning to his library we lighted cigars, and laying his head back and closing his eyes in a characteristic attitude he talked about the law as a profession, about its traditions, the relation's between bench and bar and the place of both in the development of society. When he finished and laid down his cigar my opponent arose and said to him: "Judge Braley, I can never tell you what you have done for me. This bill of exceptions is waived."

From that time, and for many years, it was my good fortune to know Judge Braley better and better, and to be greatly indebted to his strong friendship. I always think of him, not so much with regard to his great brain as to his great heart, and not so much with regard to his eminent services to his profession, both as an outstanding figure as a trial judge in the Superior Court and as a member of this great tribunal, as with regard to the human relationship that, in spite of his austere dignity, he nevertheless maintained in the court room toward the bar, the parties, the witnesses and all men. For him the Bar had to an unusual degree both respect and great affection.

Edgar W. Davis, Esquire, then addressed the court as follows:

May it please your Honors: The late Justice Braley came of that hardy seafaring race whose fame was the pioneering glory of New England. By grim determination, willingness to bear hardship, sterling honesty and integrity combined with great industry they made early America in the days of sail commercially great in the whaling and merchant services upon the seven seas. A people to whom as was said by Burke "a love of freedom, is the predominating feature."

Not only were they sailors but they also possessed sound common sense and judgment, understood the proper functions of government and had a high sense of civic duty. Many a New England town owes its moral and sound material progress to the fact that such men often assumed official responsibility in the community during their retired years.

When economic conditions brought about an abandonment of the sea their sons established great industries which were the pride and dependence of our Country and their business acumen, thrift, industry and sterling qualities built the Great West and expanded the course of empire to the Pacific Ocean.

From such people came Judge Braley. Taking up the study of law he applied to this work the same qualities which marked his entire career as a member of the bar, and as a Justice of the Superior and Supreme Judicial Courts. Those who knew him or were associated with him appreciated his great industry and capacity for hard work, his untiring study of precedent, his analytical mind and keen sense of justice combined with an admirable devotion to duty which followed him to the very end.

In Southeastern Massachusetts he was during the course of his practice one of the leading counsellors in the locality. The Bristol County Bar was considered at the time one of the strongest in the Commonwealth. Those were the days of Hosea M. Knowlton, Benjamin B. Barney, Thomas Stetson and James Brown, and often these giants of the past tried in the Old Dukes County Court House at Edgartown.

Would it not be interesting if we could visualize even after this lapse of time, the gatherings of eminent counsel at Captain George Smith's boarding house on North Water Street just before the terms of Superior Court where visiting counsel generally lodged during the terms of Court. Perhaps as a result of his visits to Edgartown and the lasting friendships he had acquired in town, Judge Braley purchased a tract of land and built for himself and family a summer home in Edgartown. However, he was more than a summer visitor, he had an interest in town affairs and welfare and with others founded the Edgartown National Bank.

His friends and neighbors always looked forward to his coming in the spring with much anticipation and pleasure. Particularly his comment on contemporary events, his reminiscences, and sound philosophy delighted those who came in contact with him.

Many opinions were prepared by Judge Braley at the Library in the Old Court House at Edgartown.

Irrespective of his attainment in his chosen vocation, when death takes from the community one beloved by it, how often can the life of such a one be summarized as, in this instance, by the man on the street who when the news comes turns to his neighbor and says "he is gone; he will be missed in this town."

Richard P. Borden, Esquire, then addressed the court as follows:

May it please your Honors; -- In this North American continent a new nation was born three hundred years ago, under auspices and conditions which have developed a racial character so distinctive as to inspire an eminent musician to write a symphony of the New World.

The Supreme Court of Massachusetts has been of great influence in moulding and building the characteristics of this world of a newer type of civilization. From the comparatively small area over which it has jurisdiction men have carried the fruits of its learning to all sections of this vast country, and reports of its decisions have guided territories in their growth to statehood.

What part has personality in thus contributing to the firm establishment of a nation? The career of Judge Braley affords an interesting basis for such consideration. In physique, in thought, in environment, he typified the founders of our national life. He was born in a rural community where his ancestors had lived since the early days of settlement. It was a community peculiar to New England, partly agricultural, partly maritime. As in many similar communities within our State, its life was broadened and enlightened by the return of its seafaring men from their journeys in the world. By some biological principle villages epitomize the national life. In the smallest may be found the farmer, the artisan, the merchant, and the exponent of law and leader in social and political life. Of the latter class was Henry K. Braley. The urge of his destiny carried him through educational institutions. It caused him to seek larger fields for the power that he realized dwelt within him; and finally the influences and opportunities which had moulded his ancestors and himself through the years brought the termination of his career in the high office of a Justice of our Court of Last Appeal.

Thus the people rule through laws expounded and interpreted by men who, through intimate contact, have absorbed their culture, genius and aspirations.

Judge Braley became domiciled in cities, but the residence of his mind and heart was the village. When his tasks were done he returned to it. His contact was with citizens slow to abandon ancient principles and willing to rely on the wisdom of experience while adapting rules of conduct to new conditions. The common law was exemplified in them. Judge Braley had a peculiar faculty to assist him in applying precedent to practice. People remember pictures and poems and persons that appeal to their imagination and made impressions on their minds. Reports of analyses of facts and judicial conclusions embodied in decisions of the Court were interesting to his mentality, and so made lasting impressions. He could cite them by name, book and page with a facility that interested bench and bar.

With such contacts and habits of thought he was eminently competent to adjust ancient learning to changing social needs. The people may well depend on men thus qualified to guard their rights and declare their responsibilities.

Chief Justice Rugg responded as follows:

Mr. Attorney General and Brethren of the Bar: This admirable memorial and these feeling tributes attest the warm esteem in which our deceased associate was held. Regret for a promising judicial career cut short before the fruitage of high opportunity is no factor in the proceedings of this occasion. Judge Braley filled the full measure of a long and active life industriously devoted to lofty ideals. Rarely has so extended a period of service or so ripe an age been allotted to one bearing the onerous burden of labor on this court. Born in the midyear of the last century, he died on January 17, 1929, when two months less than seventy-nine years old. He was appointed a justice of this court on December 24, 1902, at the age of fifty-two. For twenty-six years and twenty-four days he was a member of this tribunal. That length of time has been exceeded by only four in its history: Samuel S. Wilde, Lemuel Shaw, Samuel Putnam and Charles A. Dewey. If there be added the eleven years of his work on the Superior Court, the total of thirty-seven years surpasses, I believe, the duration of activity of any other individual upon the higher courts of the Commonwealth before or since the adoption of the Constitution. His visible contributions to the body of our jurisprudence are imposing. Opinions written by him expressing the judgments of the court were fourteen hundred and thirty-six, to be found in eighty-two volumes of the Massachusetts Reports. The first was Garant v. Cashman, 183 Mass. 13, and the last, Commonwealth v. Morris, 264 Mass. 314. He wrote no dissents and joined in only six written by others. Two alone of the sixty-three whose records of service upon this court since the adoption of the Constitution are closed have exceeded that number of written opinions. Those two are Lemuel Shaw and Marcus P. Knowlton, both chief justices. No associate justice has written so many. It would be vain to undertake to appraise their merits in detail. They are where every one may read and observe and profit. One man differeth from every other in distinctive characteristics. Judge Braley's opinions are not over-freighted with statements of facts and they are uncommonly brief. While their style bears trace of the writer's admiration of the literary excellencies of Samuel Johnson they never display mere verbal opulence. He was prompt in the performance of every duty. No matter how heavy the task, it never lagged. It was most unusual for him to carry over the summer, unwritten, a case assigned to him. Strong in body as in mind, he took a just pride in being able to say, up to a few months before the end, that he had never been absent from judicial work because of illness. He had a genius for the exacting requirements of a trial judge of the first order. His presence was impressive. In his court room no one could escape the consciousness that the law was being administered by a strong personality toward the accomplishment of right ends. Under his guidance justice never halted nor went limping by, but steadily advanced with firm step to a definite goal. Dilatory tactics on the part of counsel were repressed. Time was never wasted. The trial marched forward as swiftly as was consistent with fairness. The motions of his mind were extraordinarily quick. All his faculties were continuously alert. His rulings, based upon sound common sense, retentive memory of decided cases, and thorough knowledge of men and affairs, were instant and were steadfastly adhered to. He was a close approach to the ideal, whether sitting with or without a jury. His respect for the office of judge amounted to veneration. It increased with his experience in the administration of justice. One of his most striking and useful opinions sets forth the true functions and essential qualities of a judge conducting a jury trial. It is Whitney v. Wellesley & Boston Street Railway, 197 Mass. 495, 502, where unconsciously he described himself. He was the embodiment of the judicial figure there portrayed. He was never a mere moderator, but the dominant intellect of every trial over which he presided. He was deeply concerned in the development of equity, both in its theoretical aspects and as an instrumentality for the accomplishment of justice. Jurisdiction over that branch of the law was conferred upon the Superior Court only a few years before his appointment to that bench. The members of the bar did not at once avail themselves of the new forum in full measure. The enthusiasm, vigor, persistence, efficiency with which Judge Braley undertook the work of chancellor were potent factors in establishing confidence in the Superior Court for the administration of equity. His promotion to this bench doubtless was due in some measure to that significant achievement. The great past of this court was very dear to him. He cherished its reputation. His courage was unflinching. He was always "arm'd so strong in honesty" that alike in sunshine and in storm he bore himself with unruffled calmness.

Before his appointment to the bench he was earnest in politics and active in its partisan contests. He was honored with important public offices, to which by distinguished services he gave added lustre. He retained firm political convictions throughout life but it hardly need be said that, of course, expression of his party beliefs was held in complete restraint by the judicial proprieties of our Commonwealth. It is a fine illustration of the beneficent provisions of the Massachusetts Constitution as to the selection of judges that, although appointed to the Superior Court by a Governor of his own political faith, he was promoted to this court by one of the opposite party. He was indefatigable in study of the lives of the great judges of both England and America. His memory was tenacious of their every characteristic. Their attributes, idiosyncrasies, learning, habits were the frequent subject of his conversation. He gathered from his elders all available traditions and elements of strength of the leaders of our profession, and especially of those eminent upon the bench. He garnered through many years choice stores of information concerning those who have gone before; and he was generous in regaling his friends and associates with feasts of anecdote and reminiscence.

The son of a master mariner who had been in command on voyages to far countries and distant isles, he manifested always acute interest in maritime affairs. There was much of the tang of the sea about him. No joy in life outside his family equalled his deep satisfaction in the home in Edgartown with its broad views of harbor, and sound, and ocean. Each year he looked forward with keen zest to an early removal thither from the city, and he remained in the autumn as late as the season and duty permitted.

He loved the society of his fellows. His social tastes were wide and generous. They found one avenue of expression in warm attachment to the Thursday Club of Brookline. He was its president for several years. His papers for presentation to its members were prepared with genuine relish and with the utmost assiduity. Upon them he spent much time and study. Several of them were published. He presided over memorial services with rare felicity of discriminating speech. He felt sorely the want of a college education, and strove incessantly to repair this omission in his early training. To this end it was his aim to let no day pass without spending a substantial time in the reading of masters of literature. Like most eminent judges, he had a reverent spirit. He was a constant attendant upon public worship and a firm believer in all thereby represented. He was imbued with the history of the Pilgrim and the Puritan and of the Colony and Province out of which grew our Commonwealth. He was large hearted. It was his regret to be required by the law to decide against the poor and the unfortunate. But he always held his sympathies in complete subjection and never suffered them to sway his judgment or to warp the performance of his duty. Helpfulness to his associates was manifested on every appropriate occasion. His influence was for harmony. He possessed the universal respect and confidence of the members of the bar. His character and accomplishments were widely recognized throughout the Commonwealth and added to the strength of the court. He was crowned with the glory of many years of faithful service. Academic cognizance of conspicuous judicial attainments was expressed by Tufts College in conferring upon him the degree of Doctor of Laws honoris causa.

Severance of the close ties and the warm intimacies of this court, which bind all to each and each to all, cannot fail to cause sorrow to those who remain. There is to me a peculiar pang in this memorial. Mr. Justice Braley was the last of my seniors in service to leave the bench. He welcomed me as a neophyte to the great traditions and exalted aspirations of the fellowship of this bench. In countless ways he manifested to me his friendship and support, as he did to all his associates but especially to his juniors. He was most loyal to the titular head of the court. In a word, he was

. . . stout of heart, and strong of limb His bodily frame had been from youth to age Of unusual strength; his mind was keen, Intense, and frugal, apt for all affairs.

The memorial and a record of these proceedings may be spread upon records of the court.

The court will now adjourn.

Footnotes

1 5 Mass. 547, 557 (1809)