Are You Paying for Supplies or Services with Federal Funds?

November 2020 OIG Bulletin Article

Recently, our Chapter 30B hotline has received a number of calls asking whether Chapter 30B applies when a local jurisdiction pays for supplies or services with federal funds. The short answer is: it depends.

Generally, Chapter 30B applies even when a local jurisdiction uses federal funds to pay for supplies or services. Federal regulations require a local jurisdiction to apply state and local procurement laws for federally funded procurements, provided that the procurements also conform to federal law and regulations. See 2 C.F.R. § 200.317-318. However, Chapter 30B does not apply to federally funded procurements if following Chapter 30B would conflict with federal laws or regulations. See M.G.L. c. 30B, §1(d).

Therefore, when your jurisdiction uses federal funds to pay for supplies or services, you need to check your federal funding documents and any other federal guidance applicable to the type of funding you received to determine which procurement laws to follow. (For instance, the Department of Justice (DOJ) publishes a guide to procurements using DOJ grant funds.)

If you are still unclear about the requirements for your particular source of funding, we recommend that you contact the grantor or federal funding entity for clarification. Also, remember the following:

- Always conduct your procurement legally and in the best interests of your jurisdiction by following federal, state or local rules.

- If you seek federal reimbursement for your supplies or services procurement ‒ meaning that you make the purchase first ‒ then you generally must abide by the requirements of Chapter 30B.

- If you do not follow Chapter 30B because of federal requirements, make sure you document this in writing in your procurement file.

- Federal procurement laws and regulations typically require that you use a fair, open and competitive process, even though price thresholds, advertising requirements and contract award language may differ from the requirements of Chapter 30B. See, e.g., 2 C.F.R. § 200.319-320 (describing the competitive processes required for procurements made with federal funds).

- Purchases made directly from the federal government are exempt from Chapter 30B. See M.G.L. c. 30B, § (1)(b)(9).

- Purchases made from a vendor pursuant to a General Services Administration federal supply schedule, available for use by governmental bodies, comply with the requirements of Chapter 30B. See M.G.L. c. 30B, § 1(f).

Why is Invoice Review Important?

February 2020 OIG Bulletin Article

Public contracts account for a significant portion of every jurisdiction’s annual budget. To ensure that jurisdictions get the supplies and services they need and to combat fraud, waste and abuse, it is essential that jurisdictions carefully review all vendor payment requests. Government entities should only pay invoices after confirming that the vendor has satisfactorily delivered all goods, has performed all required services according to the contract and has submitted an accurate invoice.

Who should review invoices?

Every jurisdiction needs to review vendor payment requests to make sure they are accurate. Further, the individuals who review and approve invoices must know the contract terms, conditions and specifications. Jurisdictions therefore must dedicate staff to evaluate documents and completed work reports from contractors to make sure that they have followed the contract before issuing payment. For supply contracts, for example, jurisdictions should verify that the vendor delivered the correct items in good condition and in the correct quantities.

The right person to review an invoice depends on the type of contract, including its size and complexity. For example, someone from the public works department who supervises roadway paving should know whether the contractor completed the work and used the correct materials. As a result, that staff member should be able to determine if the invoice accurately reflects the contractor’s work. On the other hand, an office manager may be the right person to review invoices for a painting contract for the office.

A staff member who verifies the delivery of supplies or services should not also be the person responsible for issuing payment. A different person should have the authority to approve payment, and that person must also know the terms of the contract to effectively review invoices. Jurisdictions should segregate these duties in order to create an additional layer of invoice review and further protect public funds.

Contracted work, as well as the delivery of goods and services, accounts for a large portion of the Commonwealth’s spending. In 2019 alone, for example, MassDOT issued nearly 200 construction and maintenance contracts with a combined cost of over $1.2 billion.

How should you review invoices?

Check to make sure that the supplies and services that the vendor provided met the contract terms and followed the defined scope of work. For example, a roadway repair and maintenance contract should not include unrelated supplies or services, such as classroom IT equipment or roadway paving in a location not specified in the contract. Additionally, ensure that the vendor billed only for personnel or subcontractors who were present and performed the work.

Below are some general tips to keep in mind when reviewing invoices and payment requests:

- Review the contract and be familiar with its terms. Know the agreed-upon scope of work, including dates and locations where the vendor is required to deliver the supplies or services.

- Ensure that the vendor has provided identifying information on the invoice, including:

- Contract or purchase order number

- Vendor name, address, phone number and email

- Invoice date or dates of service

- Invoice number

- Description, quantity, unit of measure and unit price of supplies delivered or services performed

- Location of services performed, if applicable

- Confirm that someone from the jurisdiction has inspected the work or supplies and determined that they meet the terms of the contract.

- Confirm that the vendor billed at the rates stated in the contract or purchase order. Consider whether prevailing wage rates apply.

- Confirm that an invoice for labor accurately reflects the time that the vendor or its employees worked. Request vendor timekeeping records if needed.

- Determine whether the contract allows the vendor to bill for the items listed on the invoice. For example, verify the following:

- The items on the invoice are allowed by contract specifications and the defined scope of work.

- The vendor provided supporting documentation for the items or services on the invoice. This includes receipts or invoices from vendors or subcontractors that provided supplies or labor.

- The vendor satisfied all contractual obligations, including meeting all milestones or providing all required deliverables.

- The contract calls for reimbursement on a time-and-materials basis or scheduled fixed payments.

What if you have questions about an invoice?

When evaluating vendor invoices, jurisdictions may determine that some expenses require further review. Jurisdictions should always require the vendor to provide sufficient supporting documentation before making payment. This helps maintain the integrity of the payment process. As an example, during a roadway paving project, the invoice reviewer should confirm that the quantity and type of asphalt listed on the invoice meets the contract requirements. The reviewer should also request receipts or consult with appropriate staff to confirm that the dollar amounts on the invoice are valid before recommending invoice payment. Jurisdictions should only make payments after reviewing all invoices and supporting documentation for accuracy and completeness.

The Office of the Inspector General often reviews vendor invoices and other documents as part of its duty to prevent and detect fraud, waste and abuse. Many of our past reports highlight fraudulent or inaccurate vendor billing. Jurisdictions must remain vigilant in reviewing vendor documents to ensure that they get what they need and that public funds are properly expended. Payment reviews are a key part of contract administration, and insufficient reviews leave your jurisdiction vulnerable to improper or questionable payments to vendors.

These guidelines are not a comprehensive list, but a reminder that organizations should remain cautious when disbursing funds. The best way to safeguard public funds is to dedicate personnel and time to review invoices as an important component of contract administration.

Ensuring Proper Use of ARPA Funds by Grant Recipients

February 2022 OIG Bulletin article

The American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA), enacted in March 2021, provides state, county, local and tribal entities across the country with billions in federal aid to respond to the public health and economic effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. Massachusetts jurisdictions received over $25 billion through ARPA.

The prevention and detection of fraud, waste and abuse of public funds – always an important issue for government entities – is even more critical now that jurisdictions are receiving billions of additional dollars in ARPA funding. To promote accountability, ARPA includes requirements for the administration, monitoring and reporting of funds. Additionally, ARPA funds are subject to oversight by certain state and federal agencies, including the Massachusetts OIG.

Government entities that have received ARPA funding may be able to award grants to third parties. For example, the city of Boston used ARPA fiscal recovery funds to award more than $3.4 million in grants to 192 local arts and cultural organizations. ARPA rules may impose additional reporting requirements for grants made to third-party employers, including public disclosure of grants provided.

“Jurisdictions should build on these federal requirements to ensure that grant recipients spend grant money appropriately by implementing their own comprehensive monitoring and reporting policies.”

Insufficient reporting requirements or processes, or lack of attention to grant administration, can lead to a wide range of negative results, including project mismanagement, inappropriate use of funds and failure to comply with legal requirements. However, jurisdictions can take actions to ensure that grantees use ARPA funds in accordance with grant agreements. To promote appropriate and effective use of ARPA funds, jurisdictions should:

- Identify and understand the intended uses of the funds in the grant award agreement. Incorporate by reference any federal rules that apply to the grant award.

- Maintain open and direct communication with grantees.

- Require regular and thorough reporting from grantees relating to expenditures.

- Tie grant disbursements to deliverables, milestones or other reportable actions when possible.

- Track and maintain records of all grant-related documents, including communications, receipts and invoices.

- Include a right-to-audit clause in grant agreements. A right-to-audit clause allows a jurisdiction to request documents and engage in an active review process.

- Establish attainable program goals and targets, and understand which expenditures are allowable under federal law.

- Implement internal controls to prevent fraud, waste and abuse.

“To facilitate grant management, jurisdictions should develop clear expectations for grant programs and include this language in grant awards.”

Jurisdictions should also develop evidence-based methods of measuring performance and project goals to make sure that grantees meet those expectations. By regularly monitoring key performance indicators and tying grant payments to measurable standards, jurisdictions can determine which projects are working well and which require additional attention. Additionally, establishing and maintaining open communication with grantees regarding grant requirements and expectations will help lead to successful project completion.

Failure to implement sound grant monitoring policies that ensure proper use of ARPA funds can result in recoupment of funds by the federal government. However, developing comprehensive monitoring policies, measuring project performance and conducting grantee audits can help jurisdictions reduce fraud, waste and abuse. These practices will also ensure that ARPA funding is used for its intended purpose: helping communities recover from the devastating health and economic impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Use Data Analytics to Help Detect and Prevent Fraud, Waste and Abuse

February 2020 OIG Bulletin Article

We use data every day without realizing it. For example, perhaps one morning as you left your house, you looked outside, saw that it was raining and reached for a raincoat. Without thinking much about it, you gathered data and made a decision based on that data. Or maybe you used a more sophisticated tool to make that decision – for example, the weather “app” on your phone – but in both cases you used data to decide to wear a raincoat.

Still, working with data at all levels of government can be challenging. To assist you with overcoming this challenge, the Office of the Inspector General will publish a series of articles to help demystify data analytics and its uses. People have varying levels of comfort and expertise in using data, and these articles are designed to assist beginners and experts alike.

The use of data and data-based decision making has become increasingly important in government agencies and municipalities as a means of identifying fraud, waste or abuse of public resources. It is easy to become overwhelmed when determining how best to use this untapped resource. The words “data” and “data-driven decision-making” sound daunting; however, neither is something new.

When people think of data, often electronic spreadsheets, number-crunching and data warehouses come to mind. While data includes these things, data also includes things such as time sheets, bank statements, survey responses and water meter readings. Broadly speaking, data is any fact about an object or concept. Data is everywhere, and every function a government performs can generate valuable data.

People often make business decisions based on intuition, anecdotes or institutional lore. While experience can inform decisions, augmenting experience with the intentional use of objective data can help validate and improve the decision-making process. For instance, data analysis can reveal patterns in payroll expenditures or purchasing, track whether employees are following policies and procedures, or measure staff or vendor performance. This information is invaluable to managers. After reviewing and analyzing data, managers can follow up and review more information, identify issues and resolve them.

Data also can help identify vulnerabilities or concerns about fraud, waste or abuse. For example, when reviewing payroll records, you notice that one employee reports working more hours than personnel have access to the building. This data should alert you to the possibility that the employee may be committing fraud and that you should investigate the matter further.

The idea of using data can be intimidating, and you might think you need to be a data expert to analyze or use data. Within the Office, we have learned through experience that a wide range of staff with varied backgrounds can use data effectively. We use small samples of data, as well as “big data,” to help with everything from researching whistleblower claims to investigating individual cases of potential fraud to analyzing statewide systemic issues. We have also learned that state agencies and municipalities can start from scratch and build the capacity to rely on data as a problem-solving tool.

We hope that this article has encouraged you to use data analysis more in your work. A good way to start is by identifying data that would help you do your job. Then make sure that you have access to that data. Once you have access, you can use the data to inform your decisions and manage risks.

Collecting and Creating Data

August 2020 OIG Bulletin Article

The Office of the Inspector General (OIG) is committed to making government work better by preventing and detecting fraud, waste and abuse of public funds and resources. This goal may be accomplished, in part, by using high quality data for informed decision making and risk assessment. In the February 2020 issue of the OIG Bulletin, we published the first in a series of articles to help demystify data analytics. This second article of the series discusses how to collect data and provides examples of how procurement officials can use the data.

To use data in decision making, the data must exist in a format that can be analyzed. Some of the data within your organization may already be in an analyzable format. Some information may be in spreadsheets or in existing databases or electronic systems. If the data is not in one of these formats, do not despair! You can transform information from historical and external sources into usable data, and you can create new data.

A helpful starting point is to pull data from current and historical sources and compile it into a more data-friendly format, such as an Excel spreadsheet file. In your role as a procurement official, you may already track bids and price quotations in Excel. If not, many of the bid documents your jurisdiction retains can be used as data sources. For example, information from purchase descriptions, vendor quotations, proposal evaluation forms and invoices contain many data points. These data points include dates, prices, quantities and names that are easy to transfer into an Excel spreadsheet for future analysis.

External sources are another area from which data can be gathered and used in an analysis. For example, you can gather information about product specifications, usage and performance from relevant personnel in your jurisdiction. Then you can compile this information into a data-friendly format, like a spreadsheet.

Historical and external data sources might not provide the complete picture for your analysis. If you determine a need for data that does not al ready exist, you can also create data. Surveys are a helpful way to do this. For example, the OIG asks participants in our classes to complete surveys at the end of each class. We then use this data to improve the Massachusetts Certified Public Purchasing Official Program. Conducting a survey can be as simple as sending out an email or using a free online survey tool. The results of the survey can be transferred to a spreadsheet. Some online survey tools even analyze data for you.

Once the data has been transformed into a user-friendly format, it can be used in a variety of ways to assist with future procurements and other business decisions. For example, you can analyze vendor performance using vendor quotations, proposal evaluations and past invoices. The data from these documents can be combined to help make decisions about the award of future contracts. Historical data regarding the use of a supply or service can help procurement teams project future procurement needs and build a more effective and accurate budget. Procurement data can also help detect fraud, such as bid splitting and potential bid rigging.

Remember to consider whether your data gives you enough information to help you make decisions. Are you missing any data that would help you monitor utilization? Are there existing sources for that data? Is it something you can collect in the future? Taking incremental steps and continually finding areas for improvement will create a robust data program and help you make informed, data-driven decisions.

The OIG is developing classes to introduce local officials to specific data analysis techniques. We also plan to give an overview of some of these techniques in the next article on data in an upcoming edition of the OIG Bulletin. In the meantime, please feel free to contact us if you have any questions or ideas about data. You can reach us at (617) 722-8838 or 30BHotline@mass.gov.

Data Visualization Techniques to Detect Fraud, Waste and Abuse

February 2021 OIG Bulletin Article

The August 2020 installment of our data series discussed how to collect data and provided examples of how municipal employees can use that data to identify waste and possible fraud. In this article, we delve into two specific techniques for creating and using data visualizations, which can further aid a jurisdiction in detecting waste or fraud.

Outlier Analysis

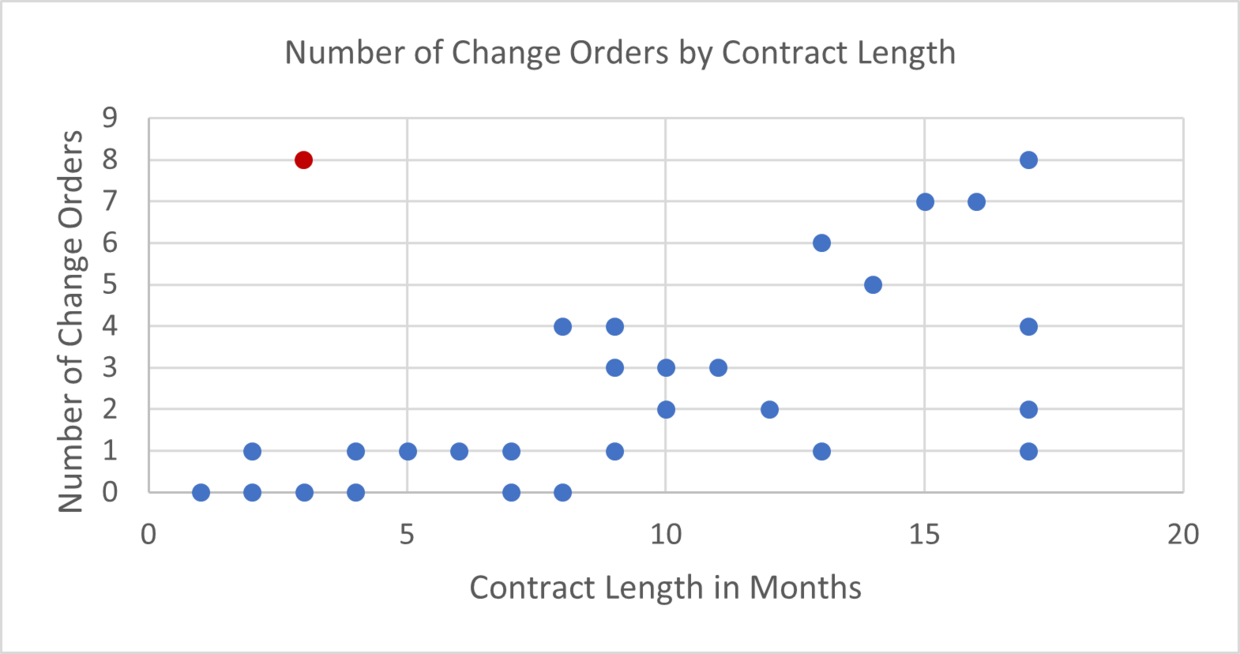

Outlier analysis, in its simplest form, compares different data points in order to identify data that stands out from the rest. For example, in the scatter plot below, each of the points represents one contract. The metrics plotted show the number of change orders (orders that modify contract terms) and the contract length in months. There is a visible correlation between the number of change orders and the contract length, which makes intuitive sense: generally, longer contracts have more change orders.

However, there is one contract, indicated by the red circle, which has a large number of change orders when compared to the length of the contract. This outlier may warrant further investigation. There may be an acceptable explanation for the high number of change orders for that particular contract, but only further review can determine whether the change orders are reasonable.

Benford’s Law

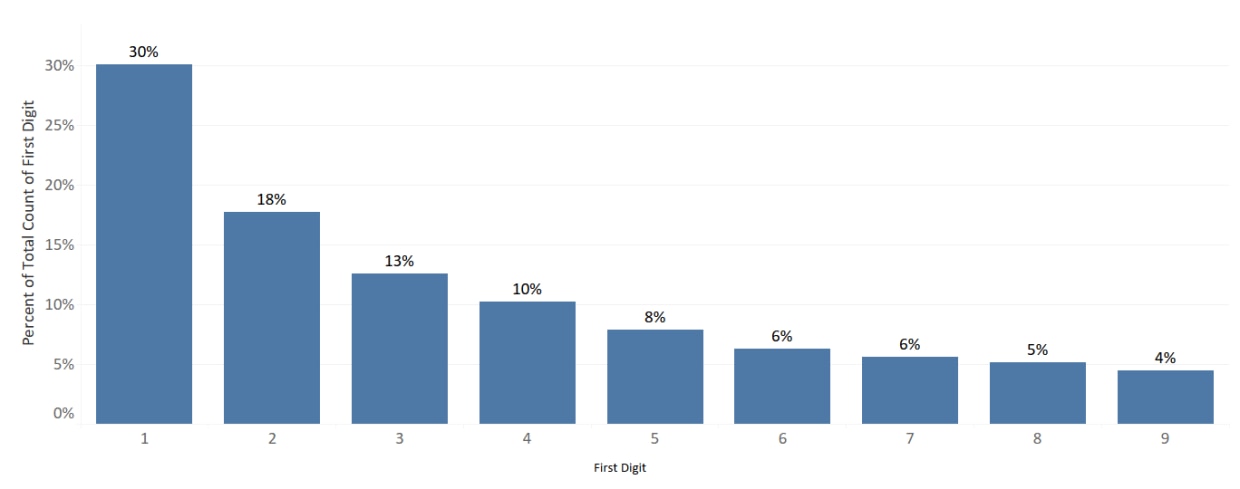

Benford’s Law is a mathematical observation about the frequency distribution of the first digits within a set of naturally occurring numbers. Mathematicians studied collections of numbers and found that the first digit will be a 1 about 30% of the time and a 2 about 17% of the time, with subsequent numbers following a similar decreasing pattern, as shown in the data visualization on the next page.

Applying Benford’s Law is another way to find outliers in your data that should be flagged for further review.

Benford’s Law is best applied to large data sets (at least several hundred records) of naturally occurring numbers with some connection, such as population data, income tax data or scientific data. Benford’s Law should not be applied to data sets that have stated minimum and maximum values or are assigned numbers, such as interest rates, telephone numbers or social security numbers.

As an example, we applied Benford’s Law to a dataset that contains the price of all items purchased by a city between 2009-2020. The following bar chart, which can be made using Excel, shows the distribution of the first digit of the purchase price for each item in the dataset, with all vendors grouped together. The bar chart shows that the purchase prices, when grouped together, closely follow the expected distribution of numbers according to Benford’s Law.

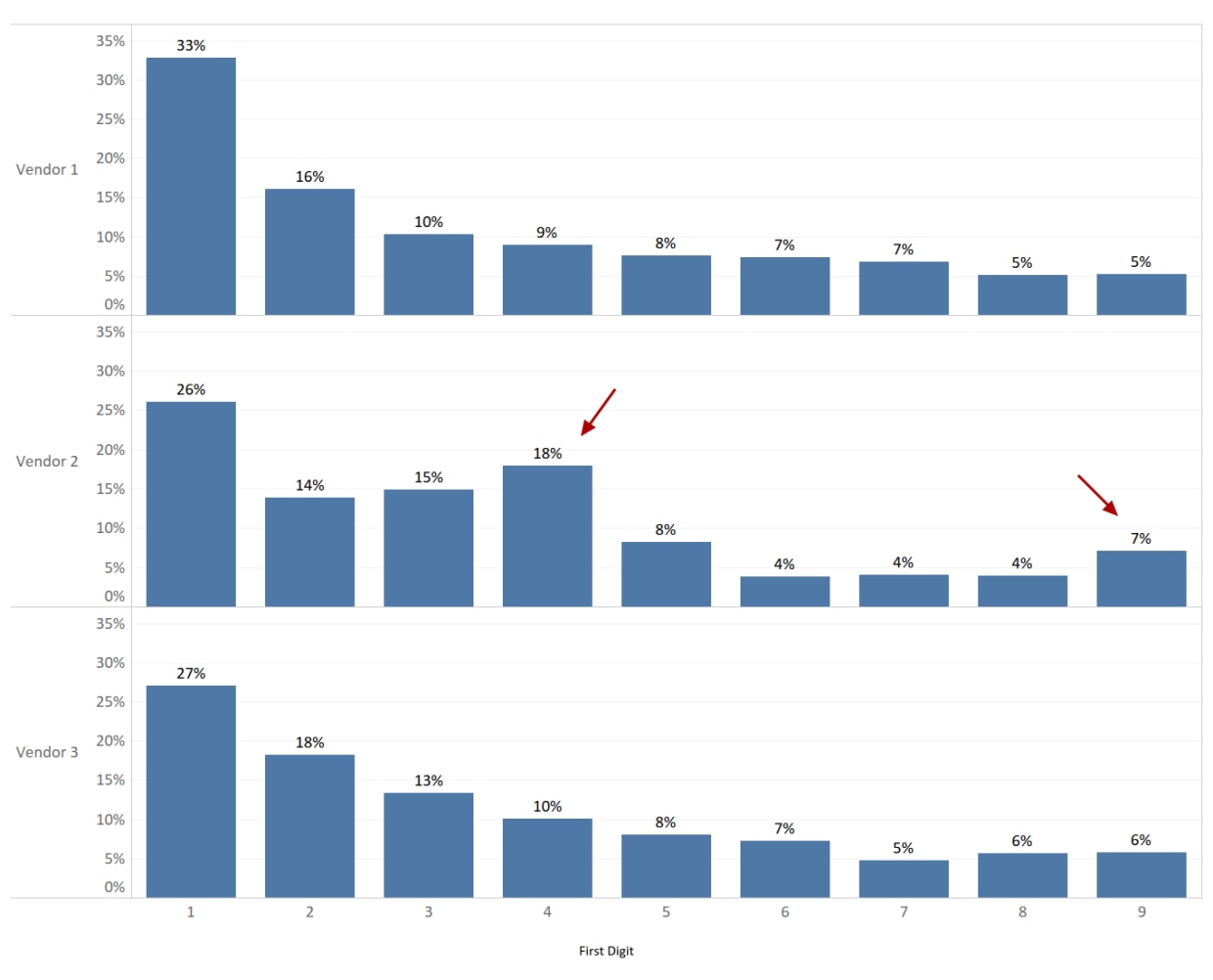

When grouping the pricing data by individual vendor, as shown in the charts below, and running the same analysis, you can see that Vendor 1 and Vendor 3 follow the expected distribution pattern. Vendor 2, however, deviates visibly at numbers 4 and 9, which could suggest falsified purchasing prices, and should be flagged for further investigation.

We hope that this article, along with the other articles in our series on data analytics, helps you feel more confident in your ability to collect and analyze data. Remember that “data” is a broad concept, and that analyzing the many different kinds of data your jurisdiction collects every day can enhance your decision-making processes.

Now that you understand some specific techniques for visualizing and analyzing data, we encourage you to apply these techniques to procurements or other business decisions facing your jurisdiction. Data visualization and analysis can be particularly useful in identifying and preventing potential fraud, waste and abuse of public resources. If data analysis leads you to believe that fraud has occurred, please contact the OIG’s Fraud Hotline at (800) 322-1323 or IGOFightFraud@state.ma.us, or fill out our online form.

Detecting Fraud Through Vendor Audits

October 2015 Procurement Bulletin Article

Most Commonwealth agencies and municipalities rely on vendors to supply the goods and services they need to operate. The majority of these goods and services are purchased using the Uniform Procurement Act, M.G.L. c. 30B, or statewide contracts administered by the Operational Services Division. When procuring goods or services, the state agency or municipal department typically executes a contract with the vendor to outline the scope of the parties’ agreement. Simply having a contract, however, does not ensure that a vendor will always bill at the agreed-upon rates, deliver the correct quantity or quality of materials, or perform the necessary activities required in the contract or by law. Governmental entities must vigilantly oversee their vendors to prevent fraud and waste in the expenditure of their limited financial resources. One key oversight tool is the vendor audit.

Why Conduct Vendor Audits?

There are many reasons to audit contracts with vendors and suppliers. The particular industry, the types of goods or services involved, the size and complexity of the contract, and the applicable regulatory requirements are just a few factors that can increase an organization’s risk of fraud, waste and abuse.

The four primary reasons to conduct audits of vendors and supplies are to:

- Ensure compliance with policies, procedures, rules, regulations and legal requirements.

- Identify conflicts of interest, fraudulent activities or other wrongdoing.

- Determine if billings are accurate and in compliance with contract terms.

- Ensure the agency received all of the purchased goods and services.

Foundation for a Vendor Audit

To set expectations from the outset – and to ensure that your jurisdiction has a right to audit – include a right-to-audit provision in contracts. Massachusetts Executive Order 195 outlines audit and oversight requirements related to vendor contracts. The executive order requires that every goods or services contract or agreement must incorporate an auditing provision permitting the government to audit the vendor’s books, records and other compilations of data relative to the performance of any provision or requirement of the contract or agreement.

Right-to-audit clauses should be specific, yet not overly restrictive, to allow the procuring entity the ability to interview key vendor personnel and review applicable documentation and records. Boilerplate audit clauses may inadvertently restrict the coverage of an audit or use vague terms that each party interprets differently, leading to disputes. Effective audit clauses include language specific to the individual contract – such as contract type, contract amount and time constraints. Other important aspects to consider are the audit period, access to records and personnel, format of records, time needed, failure-to-produce penalties and notification requirements (planned versus surprise reviews).

Which Vendors to Audit?

The first step in implementing a vendor audit program is determining who to audit. There are several techniques you could use to identify vendors to audit. These are largely based on the type of contract, the goals of the audit, specific management concerns and other relevant variables. To help prioritize which vendors to audit, consider the factors below

- Past performance: for example, businesses previously on state or federal suspension or debarment lists may pose a greater risk of noncompliance or poor performance.

- Volume of transactions or business: the volume of transactions or contracts alters the risk the government assumes in doing business with the vendor. For example, if a vendor holds 15 contracts with a municipality, the vendor can more easily bill against other contracts and fraudulently charge the government.

- Quality of contracts and documents: identify vendors with poorly written contracts or payment documents.

- Sole-source contractors: is the vendor really the only company who can provide a particular good or service?

- Suspicious invoices: even or round invoice amounts, as well as non-sequential invoices, are red flags.

- Benford’s Law analysis: this analysis may highlight a vendor with billing discrepancies that warrant further review.

Preparing for an Audit

The state agency or municipality should first identify the goal of the audit, which will determine the type of audit to perform. A “compliance audit” is the overarching term for ensuring that a vendor is complying with the terms of a contract. Within that broad term, common types of vendor audits (ranging from a less-narrow scope to a more-narrow scope) include process compliance audits, financial compliance audits, regulatory compliance audits, general compliance audits, and fraud audits. Process compliance audits evaluate whether the vendor is doing what it was hired to do. Financial compliance audits examine whether the vendor is billing appropriately. Regulatory compliance audits determine whether the vendor is following all of the laws and regulations relevant to the goods and services they provide (e.g., environmental regulations). Fraud audits encompass some or all of the elements of the above compliance audits, with a primary focus on the financial aspects and implications. The goal of a vendor fraud audit is to determine whether the vendor intentionally acted to defraud the contracting organization. Process, financial, and regulatory compliance audits might evolve into a fraud audit based upon the audit findings. Once the audit team selects the type of audit to perform, the team must clearly prepare an audit plan and outline the expected audit procedures. The audit scope and appropriate approach depend on the type of audit performed.

The audit team should also obtain buy-in and support from the vendor’s management before initiating the audit. The team needs the vendor’s support in order to get access to records and personnel, as well as to take action on findings. Therefore, support from potential stakeholders – senior management, the Board of Directors, department decision-makers – is important for a successful audit engagement. Most audits involve overcoming at least some animosity by parties who are resistant to having their work reviewed. While a right-to-audit clause gives the team the contractual authority to conduct the audit, getting buy-in from management will help make the audit more efficient and effective.

Prior to beginning the audit, the team should provide logistical information to the vendor in order to combat potential pushback throughout the audit. This includes setting specific requirements and expectations, providing an audit timeline, including when and where you will visit, who you will interview, and which documents you will need. When initiating an audit it is important to inform the vendor exactly which personnel and/or processes you will be auditing. If the vendor has subcontracted out any work, the audit team should also distinguish whether it will be reviewing the contractor’s or subcontractor’s performance.

Common Vendor Excuses to Deter Auditors

- “We’ve never been audited, so there are no benchmarks to assess our performance.”

- “You didn’t provide reasonable notice.”

- “Our ‘regular business hours’ are third shift.”

- “We cannot remove documents from our office.”

- “You don’t know how we operate.”

Requesting Vendor Information

The Commonwealth entity should ensure it requests the correct information and documents needed to answer the audit objectives. In order to maintain the vendor’s trust and cooperation, the team should only ask for information necessary to achieve the goal of the audit and documents that have a true business justification. Pertinent documents may include invoices, payment information, purchase orders, requisitions, general ledgers, cash disbursements, check registrars, transactional data histories and contract bid documents.

Identifying the key vendor personnel is also an important part of the audit. The audit team must explore and understand the vendor’s policies and procedures to adequately perform their assessment. As part of this information-gathering process, team members should strive to interview as many vendor employees as possible to corroborate their evidence and ensure the team has a complete understanding of the vendor’s current state. The team should consider gaining direct access to the vendor’s systems to facilitate its review. One of the biggest errors that an audit team can make is not adequately understanding the vendor’s processes, especially the transaction process. This can lead to drawing incorrect conclusions about the data and documentation available.

Potential Pitfalls and Red Flags

In most instances, a vendor audit is a collaborative effort between the vendor and the government entity. However, the audit team should be careful not to become too friendly with their auditees. Becoming overly friendly threatens the auditors’ independence in performing their review. Impaired independence can hinder an auditor’s professional judgment or create the appearance that his professional judgment has been compromised.

Auditors should also be on alert for process owners who explain steps as they “should be,” or who respond using words such as “usually,” “most of the time,” “supposed to” or “we try to.” Commonwealth auditors should be cautious of auditees who are overly inquisitive and interested in what the audit team is looking for or why the vendor was selected for the audit. Likewise, auditors and investigators should be prepared for individuals who become angry or aggressive in response to routine questions, or key vendor personnel who disappear during a critical part of the audit. These are common red flags for potential fraud and abuse.

Common Vendor Fraud Schemes

There is no sure-fire method to uncover vendor fraud; therefore, it is the audit team’s responsibility to remain alert and practice professional skepticism throughout the engagement. The smallest incongruity could lead to the discovery of a large fraud

Below are a few examples of the range of schemes that vendors may engage in.

- Labor Schemes

- Cross-charging multiple clients or departments for their staff’s work

- Billing for ghost or false employees

- Improper employee classification – e.g., junior staff hours billed at a supervisor’s hourly rate

- Pre-printed timesheets

- Overlapping time – vendor creates two or more timesheets for the employee for the same day

- Schedule manipulation – vendor routinely postpones or schedules jobs with higher overtime rates toward the end of the week

- Materials Schemes

- Over-purchasing materials for personal use

- Materials theft

- Product substitution - substituting lower-quality products for those agreed upon in the contract

- Failure to apply discounts, refunds and rebates

- Billing materials to one project but using for another project

- Contract Rate Schemes:

- Intentionally applying rates from one contract to another

- Billing time and equipment rates in lump-sum, unit or fixed-price contracts

Fraud, waste and abuse can occur even when comprehensive contracts are in place. Including right-to-audit clauses in vendor contracts and then performing effective audits can help reduce these risks.

Best Practice Tip: Check All Contract Terms and Conditions

February 2019 Procurement Bulletin Article

All public organizations rely on vendors to provide the supplies and services needed to operate effectively and efficiently. Recently in Massachusetts, a vendor offered a significant cost savings on supplies a local jurisdiction needed. The jurisdiction placed an order with the vendor for these supplies because of the competitive low per-unit price. After contracting with the vendor, however, the local jurisdiction began receiving large quantities of supplies that it had not ordered. When the jurisdiction tried to reduce the quantity of future deliveries, the vendor threatened to charge the jurisdiction a higher non-bulk rate. The vendor claimed that the lower per-unit price was only for bulk purchases. The jurisdiction became suspicious, researched the vendor and found no registration information on file with the Secretary of Commonwealth. The jurisdiction stopped making payments to the vendor and began to investigate whether it entered into some sort of bulk purchasing scheme.

Before engaging with any vendor, do your research and review your contract closely. Make sure the vendor is legitimate, responsible, has acceptable references and is properly registered to conduct business in Massachusetts. You must ensure that the vendors you are doing business with are legitimate and responsible. Remember to check debarment lists, as well as the Secretary of the Commonwealth’s business registration database or a local municipal clerk’s office to determine if a business is properly registered to conduct business within Massachusetts. If a vendor is not registered – beware. It is a red flag that the business may not be legitimate or well established. And always carefully read all contract terms before entering into any contract

Fraud Prevention Tip: Bid Manipulation

October 2018 Procurement Bulletin Article

Bid manipulation undermines fair competition, can cost your jurisdiction money and, in many instances, is illegal. Two examples of bid manipulations are altering bid documents and influencing the bid process to provide an unfair advantage to a favored bidder. Bid manipulation can also include allowing a vendor to submit bid documents after the public deadline or disclosing offers made by one vendor to another before the bids are opened publicly. Protect your jurisdiction and thwart bid manipulation by:

- Ensuring that submitted bids are sealed and secured physically or digitally until the bid opening.

- Restricting access to the submitted bids.

- Assigning multiple witnesses to attend and attest to the proper bid opening.

- After the official bid opening requiring a review of the bid submittals and verification of the bid results by a party not involved in the bid process.

- Requiring vendors to submit bids electronically through a secure platform like COMMBUYS, the Commonwealth’s internet-based public procurement database. This makes bid manipulation more difficult.

you suspect bid manipulation, contact the Office of the Inspector General’s fraud, waste and abuse hotline at (800) 322-1323. For more information about using COMMBUYS, contact the Operational Services Division at (617) 720-3300.

Use Competitive Procedures For Exempt Supplies And Services

April 2018 Procurement Bulletin Article

As you may know, under Section 1(b)(21) of Chapter 30B contracts for the “towing and storage of motor vehicles” are exempt from the Uniform Procurement Act. However, the Office of the Inspector General (Office) recommends that local jurisdictions use an open, fair and competitive process to acquire automobile towing and storage services. By applying Chapter 30B to the procurement of services that are otherwise exempt, you help ensure that your jurisdiction obtains services from responsible and responsive vendors at the best price or best value for your residents, even when your jurisdiction is not paying the vendor directly.

Your local jurisdiction creates a demand for towing services because local officials have the authority to have vehicles towed when there are parking violations on public property or drivers need emergency roadside assistance. Through a vehicle towing and storage contract with a local jurisdiction, a vendor stands to generate substantial revenue by regularly towing and storing vehicles. The public expects that the local jurisdiction protected their interests, including ensuring that the vendor is qualified and that the towing charges are reasonable; and vendors expect open and fair competitive processes when a local jurisdiction contracts for a service that it needs. As a result, your jurisdiction should consider using a competitive procurement process to ensure that there is open and fair competition with responsible vendors for these kinds of service contracts.

A local jurisdiction recently sought guidance from the Office related to the procurement of towing and storage of motor vehicles. The jurisdiction did not have any policies related to procuring services exempt from Chapter 30B and the jurisdiction did not procure automobile towing and storage services with a competitive process. In that case, the vendor offered to provide the jurisdiction with the towing and storage services at no cost. Nevertheless, the vendor generated substantial revenue from the contract because drivers had to pay the vendor for towing and storage charges. Thus, the jurisdiction created a ready market for a single vendor without ensuring that drivers were receiving a fair price for the towing and storage services. Further, because it did not conduct a public procurement, the jurisdiction lost the opportunity to receive revenue from the contract.

To avoid such pitfalls, your jurisdiction should approve and implement a policy outlining how to procure towing and storage services, even though it is exempt from Chapter 30B. The policy should be drafted with Chapter 30B principles in mind and should ensure that you allow for an open, fair and competitive process. A level and competitive playing field should exist for all service contracts, especially when a local jurisdiction creates a market for private vendors by prompting a demand. Further, a prequalification or screening process for vendors interested in providing certain services, such as towing and storage, helps ensure that the public is receiving services from a qualified vendor at a reasonable price. For more information about adopting a procurement policy for your jurisdiction, please see page 3 of the Bulletin.

Practice Alert: Checking Vendor Invoices

October 2017 Procurement Bulletin Article

Recently, our Office learned that a vendor included “administrative fees” in invoices issued to a housing authority under a revenue-generating contract. The vendor deducted the “administrative fee” from the monthly payment it made to the housing authority even though this was not part of the contract between the housing authority and the vendor. The contract did not entitle the vendor to charge an administrative fee and the housing authority rightly refused to pay it. In addition, the vendor did not notify the housing authority before adding the fee to the invoice. As part of its contract administration process, the housing authority discovered the improper charges when it reviewed its invoices closely

If you are not checking invoices carefully against your contract terms and conditions, your jurisdiction may be paying more that it should; or, in the case of a revenue-generating contract, your jurisdiction may be receiving less than it should. Vendors may charge fees and raise prices over the course of a contract, only if the contract allows for the same. If your contract does not permit the vendor to charge a specific fee, then your jurisdiction has a basis for contesting the application of any additional fee.

If you identify a fee or charge that is not accounted for in a contract between your jurisdiction and a vendor, contact the vendor for an explanation; or request a corrected invoice and a return of any improperly paid fees. If this fails, contact your local jurisdiction’s legal counsel because the vendor may have breached the contract. And always be vigilant in reviewing invoices for appropriate charges as a standard part of your contract administration process.