- Scientific name: Alosa pseudoharengus

- Species of Greatest Conservation Need (MA State Wildlife Action Plan)

Description

Alewife (Alosa pseudoharengus)

The alewife is a member of the herring family, very similar in appearance to the blueback herring, but the diameter of an alewife's eye is greater than the length of the snout, and alewives have a primarily white peritoneum with some dark spots but lacking the sooty black pigmentation of bluebacks. Sea run alewives can have a golden to brassy upper body as opposed to the “blueback” and silver sides seen in blueback herring. Adults typically range from 25–30 cm total length (10 to 12 in) in length. Young-of-the-year enter saltwater before they are 10 cm (4 in) long. Alewife are described as macrohabitat generalists because they can form landlocked populations, however, most alewife in Massachusetts are anadromous and therefore fluvial dependent while in freshwater. They are tolerant of warm waters as adults can remain in freshwater habitats until July. Juvenile alewife utilize freshwater nursery habitats for one to several months before emigrating to the sea in the summer or fall depending on water temperature, water quality and food supply.

Life cycle and behavior

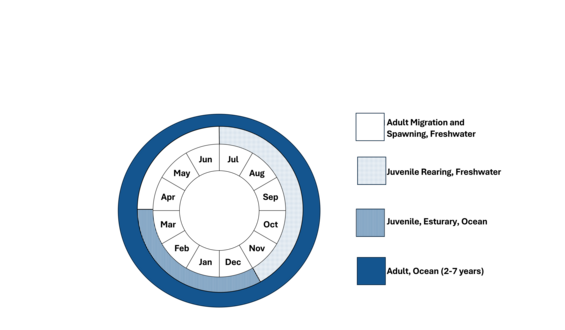

Alewives are anadromous but can establish landlocked populations. Anadromous populations spend most of their adult life in coastal marine waters and return to freshwaters to spawn in the spring. During their spawning runs, schools of alewives swim upstream, spawn numerous times over several days, and then swim downstream, often passing other schools on their way up to the spawning grounds. Spawning occurs in sluggish backwaters of rivers and in ponds. Although the annual spawning migrations are physiologically stressful, most adults survive and can repeat the process in subsequent years. After hatching, juveniles form large schools and slowly work their way downstream. They all enter saltwater before their first winter. In freshwater, young alewives feed primarily on zooplankton, and after reaching marine waters, alewives feed on a wide variety of zooplankton, small fishes, and crustaceans. They become sexually mature after three years and can reach an age of nine years.

Population status

Alewife (top) and blueback herring (bottom)

The 2024 River Herring Benchmark Stock Assessment (ASMFC, 2024) found the coastwide populations of both alewife and blueback herring were depleted relative to historic levels. The “depleted” determination was used instead of “overfished” to indicate factors besides fishing have contributed to the decline, including habitat loss, predation, and climate change.

The U.S. National Marine Fisheries Service lists alewife as a Species of Concern, meaning that it has some concerns regarding status and threats, but for which insufficient information is available to list the species under the U.S. Endangered Species Act.

Distribution and abundance

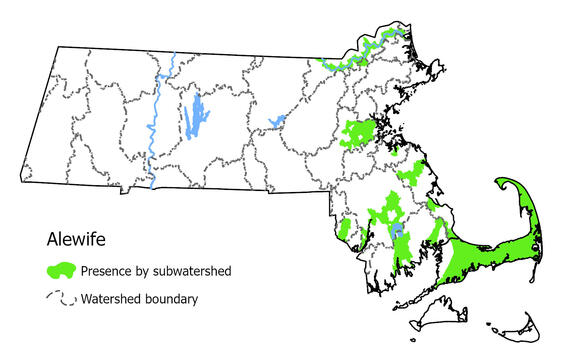

Alewives are native to the Atlantic coast of North America from maritime Canada to Florida. River herring were once common in Massachusetts and entered numerous coastal streams in the Connecticut and Merrimack rivers. Since they were often confused with blueback herring, little specific information is available regarding their historical commercial harvest, recreational harvest and metrics of population abundance. Alewife are most abundant among river herring runs in Massachusetts. Of the 170 river Massachusetts herring runs listed in the DMF coast-wide survey of anadromous fish runs (Reback et al. 2004 and 2005), 86 are listed as having alewife, 40 are listed as having blueback herring, and 44 are listed as river herring (species unknown).

Habitat

Alewives are found in shallow marine waters (<100m; 300 ft) along the continental shelf where they co-occur with blueback herring, American shad, Atlantic herring, and Atlantic mackerel. Alewives spawn in a wide range of lentic or slow-moving lotic aquatic environments. Anadromous populations require relatively easy access to the ponds in which they spawn.

Healthy habitats are vital for supporting native wildlife and plants. Explore habitats and learn about conservation and restoration in Massachusetts.

Threats

Like other river herrings, alewife populations have been reduced or eliminated in some areas by damming and pollution. Other factors that have caused the decline in this species are alteration of freshwater habitats, declines in water quality and quantity, historic over-fishing and current bycatch in other regulated fisheries.

Climate change may be a problem going forward as diadromous fish are amongst the functional groups with the highest overall vulnerability to climate change based on a recent marine and migratory fish vulnerability assessment (Hare et al. 2016). Marine habitats are affected as ocean temperature over the last decade in the U.S. Northeast Shelf and surrounding Northwest Atlantic waters have warmed faster than the global average (Pershing et al. 2015). New projections also suggest that this region will warm two to three times faster than the global average from a predicted northward shift in the Gulf Stream (Saba et al. 2016). Freshwater habitats in Massachusetts will be affected by a high rate of sea-level rise, magnitude of extreme precipitation events, and magnitude and frequency of floods and droughts (Hare et al. 2016).

Conservation

Recreational and commercial harvest of river herring was prohibited by the Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries (DMF) in 2006 out of concern over their status. As of January 2012, all directed harvest of river herring in Atlantic Coast state waters is prohibited unless states have approved sustainable fisheries management plans (SFMP). To date, two SFMP for river herring spawning run harvests have been approved.

Large cooperative aquatic restoration projects have increased in recent decades in Massachusetts. Dam removals, fishway construction and channel improvements have increased, with some documentation of spawning run abundance improvements since the harvest ban in 2006. DMF provides technical assistance to counting efforts on river herring spawning runs in Massachusetts (Nelson 2006) and annually samples biological data on spawning adults at eight of the counting stations (Sheppard and Chase 2024). Twenty-nine of the counting stations were reviewed in the recent river herring stock assessment with 11 accepted as indices of abundance (ASMFC 2024). DMF also conducts river herring spawning and nursery habitat assessments to confirm habitat suitability for river herring early life history, and document impairments and restoration potential (Chase et al. 2020). Habitat assessment reports are published in the DMF Technical Report series.

Research needs

- Information on the consequences of climate change

- Improvements to fish passage design/operation

- Greater monitoring of offshore fisheries for bycatch

- Improved information on spawning run demographics

References

This species description was adapted, with permission, from:

Karsten E. Hartel, David B. Halliwell, and Alan E. Launer. 2002. Inland Fishes of Massachusetts. Massachusetts Audubon Society, Lincoln, Massachusetts

NMFS. 2019. Status Review Report: alewife (Alosa pseudoharengus) and Blueback Herring (Alosa aestivalis). Final Report to the National Marine Fisheries Service, Office of Protected Resources. 160 pp.

ASMFC (Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission). 2024. River Herring Benchmark Stock Assessment. Washington, D.C.

Chase, B.C., J.J. Sheppard, B.I. Gahagan, and S.M. Turner. 2020. Quality Assurance Program Plan (QAPP) for Water Quality Measurements Conducted for Diadromous Fish Habitat Monitoring. Version 2.0. Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries Technical Report TR-73.

Hare, J. A., W.E. Morrison, M.W. Nelson, M.M. Stachura, E.J. Teeters, R.B. Griffis, M.A. Alexander... and A.S. Chute. 2016. A vulnerability assessment of fish and invertebrates to climate change on the Northeast US Continental Shelf. PloS one, 11(2), e0146756.

Pershing, A. J., M.A. Alexander, C.M. Hernandez, L.A. Kerr, A. Le Bris, K.E. Mills, ... and G.D. Sherwood. 2015. Slow adaptation in the face of rapid warming leads to collapse of the Gulf of Maine cod fishery. Science, 350(6262), 809-812.

Saba, V. S., S.M. Griffies, W.G. Anderson, M. Winton, M.A. Alexander, T.L. Delworth, ... and R. Zhang. 2016. Enhanced warming of the Northwest Atlantic Ocean under climate change. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 121(1), 118-132.

Reback, K.E., P.D. Brady, K.D. McLauglin, and C.G. Milliken. 2004a. A survey of anadromous fish passage in coastal Massachusetts: Part 1. Southeastern Massachusetts: Part 1. Mass. Div. Mar. Fish. Tech. Report No. 16.

Reback, K.E., P.D. Brady, K.D. McLauglin, and C.G. Milliken. 2004b. A survey of anadromous fish passage in coastal Massachusetts: Part 2. Cape Cod and the Islands. Mass. Div. Mar. Fish. Tech. Report No. 16.

Reback, K.E., P.D. Brady, K.D. McLauglin, and C.G. Milliken. 2005a. A survey of anadromous fish passage in coastal Massachusetts: Part 3. South Coastal. Mass. Div. Mar. Fish. Tech. Report No. 17.

Reback, K.E., P.D. Brady, K.D. McLauglin, and C.G. Milliken. 2005b. A survey of anadromous fish passage in coastal Massachusetts: Part 4. Boston and North Coastal. Mass. Div. Mar. Fish. Tech. Report No. 18.

Sheppard, J.J., and B.C. Chase. 2024. Massachusetts American Shad and River Herring Monitoring Report: 2019. Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries Technical Report TR-82.

Contact

| Date published: | March 3, 2025 |

|---|