- Scientific name: Anas rubripes

- Species of Greatest Conservation Need (MA State Wildlife Action Plan)

Description

American black duck (Anas rubripes)

American black ducks are moderate-size ducks, differing from most ducks in that the sexes are monomorphic with only slight differences in bill and leg color. Both sexes are dark brown with slightly lighter-colored heads and have white underwings. The males range from 53–61 cm (21–24 in) in total length, and weigh between 1,134–1,542 g (2.5–3.4 lb). Adult females are slightly smaller.

Life cycle and behavior

Black ducks are strong swimmers and will dive to evade predators and sometimes to forage. Their diet consists of plant matter, including leaves, stems, seeds, roots, and tubers found in their aquatic habitat. During breeding season, they may eat more protein-rich foods, like aquatic insects, small fish, amphibians, and crustaceans. Depending on the time of year, they may forage alone, with their mate, or in small groups.

Female American black ducks select a nest site and build the nest. She will lay 6–14 eggs and will incubate them for 23–33 days while the male defends the territory. Part way through incubation, the male tends to leave the hen. The ducklings are well-developed upon hatching and will be led by the hen to rearing areas to forage and take cover.

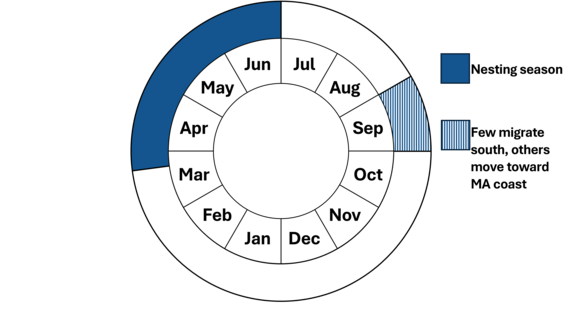

This graphic represents the peak timing of life events for American black duck in Massachusetts. Variation may occur across individuals and their range.

Population status

According to Partners in Flight, the global breeding population of American black ducks is around 700,000. As a wintering species, black ducks have remained common along coastal Massachusetts, with little evidence of an overall decline over the past 60 years (though flocks in certain areas have diminished). In recent history, an average of 19,855 black ducks have been observed on the annual Midwinter Waterfowl Survey. Although large numbers of migrants still frequent the Massachusetts coastline, numbers of American black duck nesters in the state have declined greatly.

Distribution and abundance

American black ducks were formerly much more common as a nesting species in Massachusetts than they currently are. This decline as a breeding species has occurred throughout the Northeast and the reasons behind it are unclear. Breeding Bird Atlas surveys conducted in the 1970s revealed that black ducks nested throughout Massachusetts, but more recent Northeastern States Breeding Waterfowl surveys indicate that black ducks breeding inland are rare, averaging fewer than 0.20 pairs/km2. Densities on Cape Cod were slightly higher, falling in the 0.20-0.49 pairs/km2 category. The highest densities were on salt marsh habitat where they exceeded 0.90 pairs/km2. The decline in breeding black ducks in the Northeast correlates with an increase in mallard (Anas platyrhynchos) populations. Mallards are genetically closely related to black ducks and the two species are completely inter-fertile. Hybrids were commonly observed in the 1970s and 1980s but have become less common as fewer black ducks are available for cross-breeding. Whether the mallard is displacing the black duck or merely occupying habitat vacated by black ducks is uncertain. Mallards appear to be more tolerant of human disturbance and development than black ducks.

Habitat

American black ducks utilize a variety of habitats. Breeding habitat tends to be forested wetlands, though formerly they were commonly found along major rivers and associated marshlands, from wet meadow to deep marsh, as well. Some American black ducks also nest in salt marsh areas, but because of tidal conditions, the chances of successfully achieving a successful hatch between astronomical high tides are low. Most American black ducks winter along coastal salt marsh and bay areas in Massachusetts. Both salt marsh and mussel flats are important sources of winter food, as they allow feeding across the full range of tidal fluctuation.

Healthy habitats are vital for supporting native wildlife and plants. Explore habitats and learn about conservation and restoration in Massachusetts.

Threats

The reasons behind the American black duck’s decline in the Northeast remain unclear. Loss of habitat, competition from mallards, increased human development, hunting pressure, acid deposition effects on invertebrate food supplies, and other reasons have been offered. In Massachusetts, the large decline in the number of waterfowl hunters and resulting decline in harvest makes hunting pressure an unlikely culprit. Certainly, increased development and urban sprawl have altered the habitat. Even the recent increase in beaver populations and resultant wetlands (which, in theory, should provide excellent black duck habitat) appears unable to reverse the trend of declining breeding populations. More subtle climatic changes may also be involved in the black duck’s status, as breeding populations in Canada appear to be increasing.

Conservation

Annual Mid-Winter Surveys have been discontinued but the Northeast Plot Survey and surveys by the Canadian Wildlife Service and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service continue. Cutbacks in federal funding could jeopardize future surveys.

References

Bellrose, F. C. Ducks, Geese and Swans of North America. 2nd ed. Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Stackpole Books, 1976.

Heusmann, H W and Sauer, J.R. The northeastern states’ waterfowl breeding population survey. Wildlife Soc. Bull. 28(2):355-364. 2000.

Petersen, W.R., and Meservey, W. R. 2003. Massachusetts Breeding Bird Atlas. Amherst, Massachusetts: Massachusetts Audubon Society and University of Massachusetts Press, 2003.

Contact

| Date published: | May 1, 2025 |

|---|