- Scientific name: Alosa sapidissima

- Species of Greatest Conservation Need (MA State Wildlife Action Plan)

Description

American shad (Alosa sapidissima)

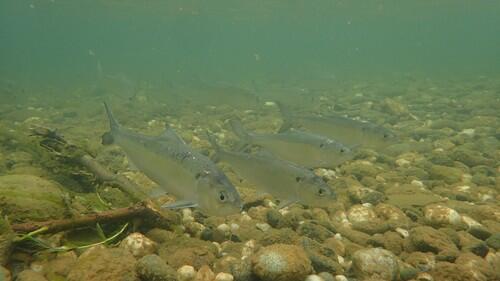

American shad is the largest member of the herring family found in Massachusetts waters, commonly reaching a length of 46-61 cm total length (18-24 in). It has more gill rakers (59-75) than all other herrings except the gizzard shad. American shad are anadromous and classified as fluvial specialists while in freshwater. They are tolerant of warm waters as adults will remain in freshwater habitats until July and juveniles spend their first summer in freshwater only entering the sea in fall as river temperatures decline.

Life cycle and behavior

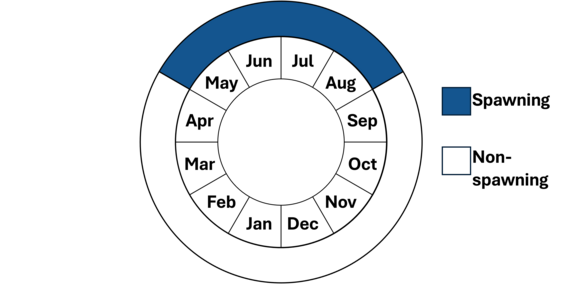

The species is anadromous, ascending coastal rivers to spawn in spring, and often migrating long distances up major rivers such as the Connecticut and Merrimack Rivers. After spawning, adult American shad migrate back to marine environments. The young form large schools and feed in freshwater until they grow to about four inches, then migrate to the sea and enter saltwater before winter. Adult American shad eat a wide variety of zooplankton, shrimp, and small fishes. In freshwater, the adults eat little and only occasionally feed on small prey. The young-of-the-year feed on small midwater copepods, ostracods, and insects while in freshwater. American shad can spawn first at the age of three, although four or five years is typical, and adults may live to 10 years of age.

Population status

The Connecticut and Merrimack River American shad populations are considered under stress due to habitat degradation, limited access to historic spawning and rearing areas, and abundance lower than management plan targets. However, the populations are considered stable enough to allow for limited recreational fisheries.

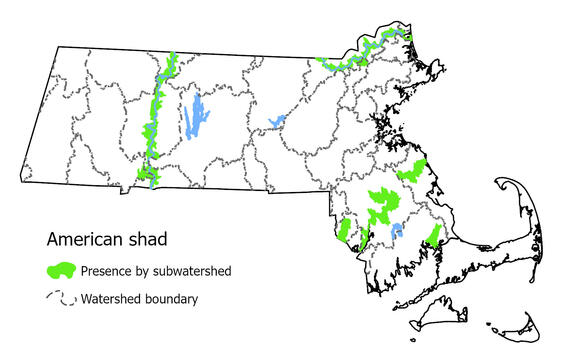

American shad are present in the Palmer, Taunton, Jones, Indian Head and South Rivers in the North River watershed, Neponset River, and Charles River in Massachusetts. The population status in these rivers is uncertain, and no fisheries are permitted.

Distribution and abundance

American shad are native to the Atlantic coast of North America from maritime Canada to Florida. Historically, American shad entered most coastal streams in Massachusetts. Damming, dredging, pollution, and other alterations of Massachusetts waters caused large declines in the mid-1800s, when American shad were eliminated from the Massachusetts portions of the Connecticut, Blackstone, and Charles Rivers. Since the mid-1950s, with new or improved fishways and fish lifts, shad numbers have increased dramatically, especially in the Connecticut and Merrimack Rivers. Repeat spawners in the Connecticut River have notably decreased from approximately 40% of the population (prior to the 1980s). Most spawning adults in a balanced New England shad population would be repeat spawners.

Habitat

Adult American shad are mostly found in waters along the continental shelf where they co-occur with river herring, Atlantic herring, and Atlantic mackerel. American shad spawn in a wide range of lotic environments connected to the ocean.

Healthy habitats are vital for supporting native wildlife and plants. Explore habitats and learn about conservation and restoration in Massachusetts.

Threats

Like other anadromous fish, American shad populations have been reduced by multiple factors such as overfishing, inadequate fish passage at dams, predation, pollution, water withdrawals, channelization of rivers, changing ocean conditions, and climate change. The Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commissions conducts a coast-wide population assessment of American shad. The last assessment found shad populations to be depleted from historical levels (ASMFC 2020).

Climate change may be a problem for American shad going forward as diadromous fish are amongst the functional groups with the highest overall vulnerability to climate change based on a recent marine and migratory fish vulnerability assessment (Hare et al. 2016). Marine habitats are affected as ocean temperature over the last decade in the U.S. Northeast Shelf and surrounding Northwest Atlantic waters have warmed faster than the global average (Pershing et al. 2015). New projections also suggest that this region will warm two to three times faster than the global average from a predicted northward shift in the Gulf Stream (Saba et al. 2016). Freshwater habitats will be affected by a high rate of sea-level rise, as well as increases in annual precipitation and river flow, magnitude of extreme precipitation events, and magnitude and frequency of floods (Hare et al. 2016).

Conservation

The Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries (DMF) assists cooperative efforts to monitor shad spawning runs in the Merrimack River and conducts an annual backpack electrofishing survey of shad in the South River and Indian Head River and a beach seine survey for juvenile shad in the Taunton River. DMF and MassWildlife are presently in collaboration with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to stock juvenile American shad in the Taunton River (Chase et al. 2022; Mattocks et al. 2022).

Massachusetts ended the commercial harvest of shad in 1987. Recreational harvest was closed for all rivers except the Connecticut, Merrimack, and their tributaries in 2014 and the creel limit was reduced from 6 to 3 at that time. Improved upstream and downstream passage of American shad at the mainstem dams on the Merrimack and Connecticut Rivers has been a priority during the federal relicensing of these large hydroelectric facilities.

Research needs

- Information on the consequences of climate change

- Improvements to fish passage design/operation

- Greater monitoring of offshore fisheries for bycatch

- Improved monitoring of spawning run demographics in small watersheds

References

This species description was adapted, with permission, from:

Karsten E. Hartel, David B. Halliwell, and Alan E. Launer. 2002. Inland Fishes of Massachusetts. Massachusetts Audubon Society, Lincoln, Massachusetts

ASMFC. Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission. 2020. American Shad Benchmark Stock Assessment and Peer Review Report. Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission. Arlington, VA

Chase, B.C., S. Mattocks, and K. Cheung. 2022. American Shad Habitat Plan for the Taunton River, Massachusetts. Prepared by Mass. Div. of Marine Fisheries, Mass. Div. of Fish and Wildlife, and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

Mattocks, S., B.C. Chase, and K. Cheung. 2022. American Shad Monitoring Plan for the Taunton River, Massachusetts. Prepared by Mass. Div. of Marine Fisheries, Mass. Div. of Fish and Wildlife, and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

NMFS. 2019. Status Review Report: Alewife (Alosa pseudoharengus) and Blueback Herring (Alosa aestivalis). Final Report to the National Marine Fisheries Service, Office of Protected Resources. 160 pp.

Hare, J. A., W.E. Morrison, M.W. Nelson, M.M. Stachura, E.J. Teeters, R.B. Griffis, M.A. Alexander... and A.S. Chute. 2016. A vulnerability assessment of fish and invertebrates to climate change on the Northeast US Continental Shelf. PloS one, 11(2), e0146756.

Pershing, A. J., M.A. Alexander, C.M. Hernandez, L.A. Kerr, A. Le Bris, K.E. Mills, ... and G.D. Sherwood. 2015. Slow adaptation in the face of rapid warming leads to collapse of the Gulf of Maine cod fishery. Science, 350(6262), 809-812.

Saba, V. S., S.M. Griffies, W.G. Anderson, M. Winton, M.A. Alexander, T.L. Delworth, ... and R. Zhang. 2016. Enhanced warming of the Northwest Atlantic Ocean under climate change. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 121(1), 118-132.

Contact

| Date published: | April 10, 2025 |

|---|