- Scientific name: Anas discors

- Species of Greatest Conservation Need (MA State Wildlife Action Plan)

Description

Blue-winged teal (Anas discors)

The blue-winged teal is among the smallest ducks in North America, weighing 230–545 g (8.1–19.2 oz). They are 36–41 cm (14.2–16.1 in) long and have a wingspan of 56–62 cm (22.1–24.4 in). The most distinguishing feature in flight is the large gray/blue patch on the wing of both sexes, a feature shared with cinnamon teal and northern shovelers. Male blue-winged teal have a distinct white crescent on the face, making it easily recognizable. Overall, both sexes have brown-plumaged bodies. Breeding males will have dark specking on the breast. Female blue-winged and cinnamon teal are nearly indistinguishable in body plumage. Cinnamon teal, however, are a western species rarely encountered in New England.

Life cycle and behavior

Blue-winged teals are commonly seen alongside other dabbling duck species, often around the edges of ponds hiding among vegetation to forage and rest. Blue-winged teals are dabbling ducks and very rarely dive. They eat aquatic insects, vegetation, and grains.

Female blue-winged teals decide on a nesting site. Nest sites are slightly above, but close to, water and covered by vegetation on all sides and above. The female will lay 6–14 eggs and will incubate them for 19–29 days. Mating pairs may split up during incubation and adults will form new bonds with other individuals in winter or spring.

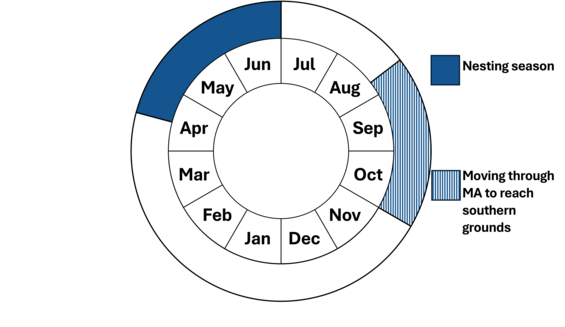

This graphic represents the peak timing of life events for blue-winged teal in Massachusetts. Variation may occur across individuals and their range.

Population status

Partners in Flight estimates the blue-winged teal global breeding population to be almost 8 million, making them one of the most abundant ducks on the continent. The blue-winged teal was likely never common as a nesting bird in Massachusetts. It was reported as breeding regularly but locally at various sites across the state in the early 1900s, a status it maintained into the 1970s, most prominently in northeastern Massachusetts, but with some evidence of breeding in the southeastern and central parts of the state. However, by the second Massachusetts Audubon Breeding Bird Atlas in the early 2000s, the species had disappeared from 15 blocks, including all of southeastern Massachusetts. A similar decline was noted in other regions of the northeastern U.S., though populations in the prairies remained high.

Distribution and abundance

The blue-winged teal has two populations. One is west of the Appalachian Mountains, with particularly high populations in the prairie pothole country of the United States and Canada, extending to California and Alaska. The other population nests along the Atlantic seaboard from New Brunswick to North Carolina. An early migrant, the blue-winged teal begins moving through Massachusetts by late August and is largely absent from the state by late October. The blue-winged teal winters along the southern Atlantic and Gulf coasts south to central Peru and Argentina. Overall, the blue-winged teal is one of the most abundant waterfowl species in North America.

Habitat

The blue-winged teal nests in shallow and deep freshwater marshes and the upper reaches of salt marshes. It frequents the same areas outside the nesting season, as well as grassy upland sites. Nests in the Concord area have been located on tussocks in shallow marshes.

Healthy habitats are vital for supporting native wildlife and plants. Explore habitats and learn about conservation and restoration in Massachusetts.

Threats

The causes for the decline in nesting blue-winged teal in the northeast is poorly understood but follows a trend for other nesting waterfowl species on the periphery of their ranges. Fall migrant populations appear little changed over the last 50 years, although annual changes in numbers are not unusual. Blue-winged teal are vulnerable to wetland habitat loss. While USDA’s Conservation Reserve Program has helped incentivize farmers to leave some of their fields for grassland nesting habitat, the program’s enrollment has decreased and has resulted in less suitable nesting habitat for blue-winged teal. Although DDT was outlawed in Massachusetts in 1970, blue-wing teal are still threatened by exposure to pesticides and insecticides.

Conservation

Surveys in northeastern United States do not detect blue-winged teal in the area as their numbers are too low. Wetland laws should aim to address habitat loss, particularly shallow marsh habitat.

References

Bellrose, F.C. Ducks, Geese & Swans of North America. Wildlife Management Institute and Illinois Natural History Survey. Stackpole Books,1976.

Griscom, L., and Snyder, D.E. Birds of Massachusetts. Peabody Museum, Salem, MA: Anthoensen Press, 1955.

Petersen, W.R. and Meservey, W.R. Massachusetts Breeding Bird Atlas. Amherst, MA: Massachusetts Audubon Society and the University of Massachusetts Press, 2003.

Sauer, J.R., Hines, J.E., Fallon, F.E., Pardieck, K.L., Ziolkowski, Jr., D.J., Link, W.A. The North American Breeding Bird Survey, Results and Analysis 1966-2013. Laurel, MD: 2014.

Veit, R.R., and Petersen, W.R. Birds of Massachusetts. Natural History of New England Series. C.W. Leahy, Ed., Massachusetts Audubon Society. 1993.

Contact

| Date published: | May 1, 2025 |

|---|