- Scientific name: Somateria mollissima

- Species of Greatest Conservation Need (MA State Wildlife Action Plan)

Description

Common eider (Somateria mollissima)

Common eiders are among the largest of all ducks. The drake (male) is black and white with a white back and head and black underneath. Drakes also have black on the top of head. Females are barred brown overall. Both sexes have notably wide and extended bill processes. Eiders are chunky-looking birds. The males range from 55–66 cm (22–26 in) in length and weigh 1.77–2.09 kg (3.9–4.6 lb). Adult females range from 53–61 cm (21–24 in) in length and weigh 1.18–1.72 (2.6–3.8 lb).

Life cycle and behavior

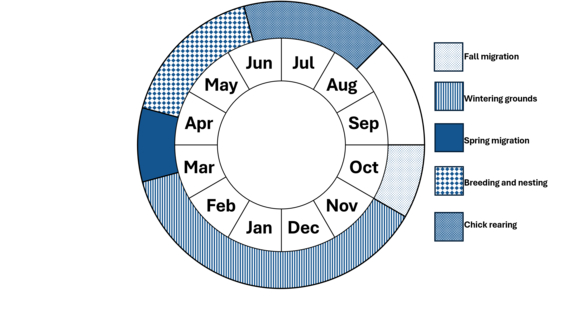

This graphic represents the peak timing of life events for common eider in Massachusetts. Variation may occur across individuals and their range.

Common eiders are migratory birds but some may stay in the same area year-round. Migration to breeding grounds happens each spring, peaking in late March and early April. In late September, adult and immature eiders flock together and prepare to migrate to their wintering grounds in the fall.

Common eider pairs can be monogamous and will sometimes breed with the same individuals for multiple seasons. Courtship and breeding begin in the spring. The males use a variety of calls to attract a female. In the summer, the female will lay one brood with 1–8 eggs (4 on average). The olive-green eggs will hatch after a 24–28-day incubation period. The young eiders often gather into larger groups called creches that are watched over by a few adult females.

Population status

Common eiders are among the most abundant of wintering waterfowl, but numbers can fluctuate greatly from year to year. Previous Mid-winter Waterfowl Survey counts had found 20,000–120,000 birds in Massachusetts, however these surveys were discontinued and there are no recent estimates for wintering eiders in the state. The number of breeding eiders have sharply declined in the historic Gulf of Maine region, but breeding colonies have been established in Massachusetts through transplants to Penikese Island in the mid-1970s, which have since expanded all the way to Cape Ann, Massachusetts.

Distribution and abundance

Common eiders are northern nesters. The American common eider (Somateria mollissima dresseri) breeds from central Labrador to southern Maine, though breeding colonies have also become established in Massachusetts. They winter from the island of Newfoundland to Massachusetts, primarily north and east of the Cape Cod Canal, but greater numbers are now wintering in Buzzards Bay.

Habitat

American common eiders nest on small and large offshore islets and islands along the northern Atlantic coast and the St. Lawrence River estuary. As island nesters, they often nest in dense colonies. Nest sites may be under shrubs, driftwood, or grasses and weeds. Eiders winter along coastal waters in bays, large estuaries, and on the open ocean. Eiders feed almost entirely on animal matter, mainly mussels. Blue mussels are especially important in the diet of the American race. Eiders typically feed in waters 1.8–7.6 m (6–25 ft) deep but can dive to twice that depth.

Healthy habitats are vital for supporting native wildlife and plants. Explore habitats and learn about conservation and restoration in Massachusetts.

Threats

Eiders have low reproductive potential, with females not nesting until 2 or 3 years old and then laying only a clutch of 4 eggs. This creates a potential for over-harvest of this game species. Uncontrolled harvesting on both breeding and wintering habitat for blue mussel and finfish, as well as aquaculture, sea urchin, and rockweed harvest, threaten the species, as does summer residential development on offshore nesting islands. Nest predation by increased populations of large gulls may limit productivity. Frequent outbreaks of epizootic diseases in nesting colonies can decimate local populations. Oil spills may pose a risk, as well as contamination of benthic food supplies. The effects of climate change may alter or amplify all of these threats.

The New England states and some Atlantic Canada provinces have taken measures to restrict the harvest of eiders by reducing bag limits. In Massachusetts, beginning with the 2017–18 season, the sea duck bag limit was reduced from 7 to 5. In the 2022–23 season, sea ducks became part of the regular duck bag limit of 4, of which no more than 3 could be eiders and only 1 could be a hen. Declining numbers of waterfowl hunters further reduce harvest pressure on eiders. Limiting access to some islands in Boston Harbor during the nesting season would be desirable. Meanwhile, the USFWS should be encouraged to resume special sea duck surveys initiated in 1991 but suspended in 2003, and the eider should be included in colonial waterbird nesting surveys in Massachusetts.

Conservation

Winter coastal surveys from the Maritime to Long Island, NY should be resumed. Additional studies could provide further insight into common eider management needs in New England. Research should be conducted to determine the threats of commercial shellfish harvesting on common eiders.

References

Bellrose, F. C. Ducks, Geese and Swans of North America. 2nd ed. Stackpole Books, Harrisburg Pennsylvania. 1976.

Heusmann, H W. “Responsive management for eiders.” Massachusetts Wildlife 49, no. 3 (1999):2-7.

Serie, J., and B. Raftovich. “Atlantic Flyway waterfowl harvest and population survey data.” U.S. Fish and Wildlife Serv. Laurel, Maryland. July 2001.

Contact

| Date published: | May 1, 2025 |

|---|