- Scientific name: Semotilus corporalis

- Species of Greatest Conservation Need (MA State Wildlife Action Plan)

Description

Fallfish (Semotilus corporalis)

Fallfish are the largest and longest-lived minnow native to eastern North America and have a moderately compressed body with large, distinct silvery scales. They have a rounded snout that is slightly overhanging and contains a small fleshy barbell in the groove between their upper and lower jaws. Their dorsal fin and anal fins both contain 8 rays, and they have 43-50 lateral line scales. During the spawning season, reproducing males develop large tubercles (protruding bumps) on their heads that are used for territory defense during reproduction.

While coloration varies slightly dependent on the waterbody and season, fallfish have an olive to golden brown dorsal surface, a black stripe along their back, and a distinctly silver side. Juveniles of this species have a black stripe from their operculum to the caudal fin base and a dark caudal spot. Adults typically are around 300 mm (12 in), with the largest recorded Massachusetts specimen measured at 480 mm (19 in).

Male fallfish springtime breeding tubercles used for territory defense.

Life cycle and behavior

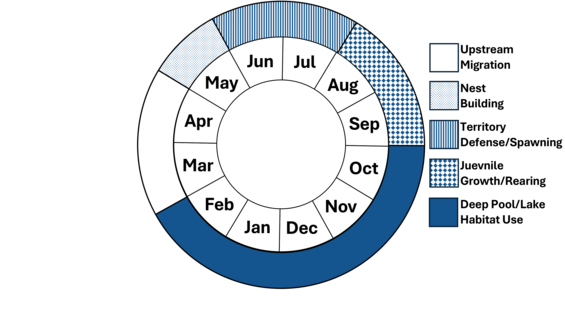

This species is considered a lithophilic spawner that seeks out gravel and rock for spawning habitat. During the spring breeding season in May, adults migrate to areas with gravel and create a pyramidal nest by moving small stones with their mouths. Some of these nests can be nearly a foot tall and are often used by several species of fish for spawning. The large size of fallfish allows them to create such large structures that others would not be able to construct. Spawning aggregations are often communal and involve complex social hierarchies based on the behaviors of male individuals. Sexual maturity is reached in males by their third spring and in females by their fourth spring. Following spawning and hatching, adults and young-of-year individuals disperse downstream where they reside for the remainder of the year. During spawning this species provides important energy transfer by producing large amounts of eggs that are consumed by multiple fish species.

Fallfish are generalist feeders, eating plankton until they are about 38 mm (1.5 inches) in total length and gradually switching to larger foods such as algae, insects, crayfish, and small fishes. It takes five years for this species to reach about 200 mm (8 inches) and almost 10 years to reach maximum size.

Population status

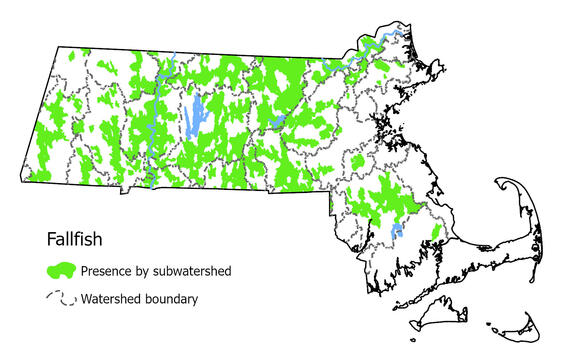

The population status of this species is unknown but historical records suggest that this species used to occur in higher abundances in the eastern part of the state, such as the Charles River basin. Currently, this species is captured during standard fish surveys in streams and rivers throughout its distribution in the state.

Distribution and abundance

In North America, this native species has a wide range spanning from northern Canada all the way south to Virginia and can be found as far west as the Great Lakes region. In Massachusetts, this species is rare in the eastern part of the state but is very common in the Connecticut River Basin and can be readily captured in the central and western parts of the state. Sampling suggests that some smaller populations remain in river and stream habitats near Cape Cod. Historical records indicate that this species used to occur in the eastern part of the state such as the Charles River basin but have not been captured for over 40 years in this basin.

Data from 1999-2024 from annual surveys.

Habitat

The fallfish is considered a fluvial specialist in Massachusetts as there are no known samples from lakes and ponds. The species is found in riverine habitat class and present in gently sloping and steep cool water rivers and streams with rock and gravel substrates. Throughout the year, fallfish occupy slow-moving waters and pools where they can easily forage away from the current. During the spawning season, this species moves upstream into tributaries containing moderate flow, clear water, and rock and gravel for spawning. Fish hatch within about six days and as they grow eventually distribute downstream to areas containing aquatic vegetation.

Healthy habitats are vital for supporting native wildlife and plants. Explore habitats and learn about conservation and restoration in Massachusetts.

Threats

Juvenile fallfish

Seasonal warming associated with climate change is likely affecting the timing of reproduction and habitat usage, and could be negatively impacting this cool water species. Increases in water temperatures and decreases in precipitation during the summertime can reduce available habitat for this species to forage, thermal moderation, and avoid predation. These impacts are exacerbated in streams that are heavily altered by water supply withdrawal. Extreme flow events during the spring can impact the availability of spawning habitat by covering gravel and rock with fine sediment, resulting in reduced reproductive outputs. Additionally, more direct threats like dams can cause sedimentation and decreases in aquatic connectivity, impacting movement to spawning grounds and the quality of these habitats. This species is meso-tolerant to pollution and has declined in aquatic systems experiencing reduced water quality associated with impervious surfaces, increased nutrients, and inadequate wastewater drainage systems.

Conservation

Survey and monitoring

Efforts to document this species and their abundance is conducted during fish community assessments and is successful at capturing individuals in multiple locations in the state. However, compared to historic accounts this species appears to be declining throughout its range in the state.

Management

Management on this species focuses on river and stream restorations improving habitat connectivity such as dam removal, culvert replacement, and reconnecting streams to their floodplains. These actions help remediate the effects of 300 years of channelization in Massachusetts and help restore access and habitat quality of spawning tributaries, as well as providing deep bend pools that are used for summertime and winter refugia during times of low water or adverse water temperatures.

Research Needs

A better understanding of the movements of this species could help update their range in the state and identify important habitat connectivity supporting this native species. Specific research on sedimentation processes in areas of urbanization and agriculture could help protect and manage important gravel and rocky spawning grounds necessary for this species to reproduce. Additionally, historic data suggest this species has declined in the eastern part of the state and requires further sampling and research to understand the reasons for these declines.

References

Hartel, K.E., Halliwell, D.B., Launer, A.E. Inland Fishes of Massachusetts. Lincoln, MA: Massachusetts Audubon Society, 2002.

Page, L.M., Burr, B.M. Peterson Field Guide to Freshwater Fishes of North America North of Mexico. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 2011.

Contact

| Date published: | April 15, 2025 |

|---|