- Scientific name: Larus marinus

Species of Greatest Conservation Need (MA State Wildlife Action Plan)

Description

Great black-backed gull (Larus marinus)

The great black-backed gull is the largest and heaviest gull in the world. They are 71-79 cm (28-31 in) long, weigh 1,300-2,000 g (46-70 oz), and have a wingspan of 146-160 cm (57.5-63 in). Adults are mostly white with a black back and wings and have a yellowish bill with a red spot near the tip. Immature gulls are checkered gray-brown and white above and have white-based, black-tipped tails, black bills, and black flight feathers. Juveniles transition to adult plumage at around 4 years. Overall, this gull appears heavy and robust with a heavy bill. In adults, there is no significant seasonal or sexual difference in plumage.

Life cycle and behavior

The great black-backed gull’s reputation is built on its apparent bullying of smaller gulls and terns, as well as its voracious appetite for the eggs and young of other birds. They are often seen foraging and roosting among other species of birds.

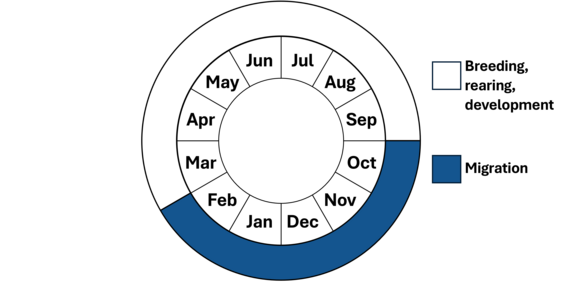

Great black-backed gulls are monogamous, and males display and call to attract a mate. The adults typically nest in loose colonies and defend the small territory around the nest. They will build their nest next to logs, bushes, or rocks to hide it from nearby gulls or predation. The pair will build multiple nests but will only use one. The female will lay 2-3 eggs and incubate them for 30-32 days. While young are mobile after 24 hours, they remain in the nesting territory for over a month and begin to fly at around 45 days. After about 8 weeks, young are fully independent.

Population status

Formerly unheard of as a breeding species in the Commonwealth, the great black-backed gull is now relatively common along coastal Massachusetts. Even so, the North American Breeding Bird Survey found that populations have an annual decline of 1.6% range-wide between 1966-2022.

Distribution and abundance

In North America, the breeding range includes coastal areas (particularly on offshore islands) extending from Labrador to North Carolina and along large inland waterbodies (e.g., Great Lakes, Lake Champlain). Historically, great black-backed gulls did not nest in Massachusetts and were first documented as a breeding bird in the state in 1931. Since that time their populations have dramatically increased, thought to be a result of increased food resources associated with a human dominated landscape (e.g., landfills). However, the Coastal Waterbird Census coordinated by the Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife revealed that the breeding population has steadily declined over the last several decades from nearly 15,000 pairs in the mid- 1990s to under 4,000 pairs in 2018, a pattern similar to that found for the American herring gull.

Habitat

Great black-backed gulls nest in a variety of habitats including small islands, rocky islets, salt marshes, dredge-spoil islands, barrier beaches, dunes on barrier islands, flat-topped stacks, and rooftops. They often breed in areas with American herring gulls, but the great black-backed gull prefers more open and higher microhabitats. They use open areas as roosting sites, including parking lots, fields, helipads, and airport runways.

Healthy habitats are vital for supporting native wildlife and plants. Explore habitats and learn about conservation and restoration in Massachusetts.

Threats

Pesticides, pollutants, storms, habitat degradation, and decline in food resources could affect local populations. Like other island nesting species, the great black-backed gull is vulnerable to sea level rise. Colonial nesting sites can be vulnerable to disturbance by people or predators. Collisions with offshore wind turbines pose a potential future threat to the species in Massachusetts. Plastic trash in the environment poses a threat as it can be mistaken as food by seabirds and shorebirds and ingested or cause entanglement. Ingested plastics, common for seabirds, can block digestive tracts, cause internal injuries, disrupt the endocrine system, and lead to death. Entanglement from fishing gear and other string-like plastics can cause mortality by strangulation and impairing movements.

Conservation

Protection of offshore colonial nesting sites and minimizing disturbance within the nesting colonies is important for the conservation of the species. Keeping mammalian predators (e.g., Norway rats) off islands that host nesting colonies is important for colony persistence. Avoid or recycle single-use plastics and promote and participate in beach cleanup efforts.

References

Good, T. P. (2020). Great Black-backed Gull (Larus marinus), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (S. M. Billerman, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.gbbgul.01

Melvin, S. 2010. Survey of Coastal Nesting Colonies of Cormorants, Gulls, Night-Herons, Egrets, and Ibises in Massachusetts, 2006-2008. Massachusetts Natural Heritage and Endangered Species Program.

Sauer, J.R., J.E. Hines, J.E. Fallon, K.L. Pardieck, D.J. Ziolkowski, Jr., and W.A. Link. 2022. The North American Breeding Bird Survey, Results and Analysis 1966 - 2022. Version 01.30.2015 USGS Patuxent Wildlife Research Center, Laurel, MD.

Walsh, J., and Petersen, W.R. 2013. Massachusetts Breeding Bird Atlas 2. Massachusetts Audubon Society and Scott & Nix, Inc.

Contact

| Date published: | May 14, 2025 |

|---|