- Scientific name: Histrionicus histrionicus

- Species of Greatest Conservation Need (MA State Wildlife Action Plan)

Description

Harlequin duck (Histrionicus histrionicus)

Drake (male) harlequin ducks are among the most unusually colored of all ducks. The basic body color is slate blue, but the head and body are covered with a series of white crescents and spots, offset by chestnut flanks and a chestnut stripe on either side of the head. Females are a nondescript brown with a whitish patch on the cheek and whitish spots in front of and behind the eye. From a distance, both sexes appear dark. Harlequins are small ducks. The males range from 34–46 cm (13.4–18.1 in) in length and weigh 590–726 g (1.3–1.6 lb). Adult females are slightly smaller.

Life cycle and behavior

Harlequin ducks are strong swimmers and are capable of diving up to 21 m (70 ft) deep. They are known for being able to weather rough water conditions. They primarily eat aquatic invertebrates or small fish they collect on their deep dives. Harlequin ducks are social and will form large groups outside of the breeding season.

While harlequin ducks will spend the winter on Massachusetts coastlines, they mate in their northern breeding grounds. Harlequin ducks are monogamous and begin pairing during the winter. Once at their breeding territory, the female will select a nest site, sometimes using an old nest site. The female will lay 4–8 eggs and incubate them for 27–29 days. The males will leave for the molting grounds after the start of incubation. Ducklings are able to forage for insect shortly after hatching and begin diving around 3–4 weeks old.

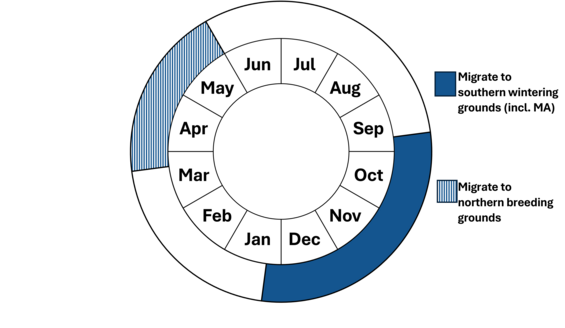

This graphic represents the peak timing of life events for harlequin duck in Massachusetts. Variation may occur across individuals and their range.

Population status

The eastern North American population likely numbers no more than a few thousand birds. In Massachusetts, harlequins are found in small numbers along Cape Ann, Plymouth, and Martha’s Vineyard with a state total of only a few hundred wintering birds.

Distribution and abundance

Harlequin ducks are northern nesters with populations in western North America, eastern North America, Greenland and Iceland. In eastern North America, they breed in Quebec, with small numbers in Newfoundland and northern New Brunswick. Radio tagging has suggested some movement of harlequins between eastern Canada and Greenland. Wintering is primarily in Maritime Canada south to Rhode Island, with some birds occurring on the Great Lakes. Concern over perceived declining numbers led to closure of the hunting season in the U.S. in 1989. In 1991, they were listed as an endangered species in Canada. Since then, more recent reviews of the literature suggest the decline was not as pronounced as originally thought, but poor recordkeeping during the early years of survey work make assessing population changes questionable. A recent increase in numbers may be attributed to better surveying and monitoring. There is scant evidence that the eastern race was ever abundant, likely due to their special habitat requirements.

Habitat

Harlequin ducks use relatively specialized habitat, breeding along fast-flowing, sub-arctic rivers and streams and wintering on turbulent coastal marine habitat, especially along rocky shorelines. They feed in somewhat shallow water, diving for food in water only 1–3 m (3.28–9.84 ft) deep.

Healthy habitats are vital for supporting native wildlife and plants. Explore habitats and learn about conservation and restoration in Massachusetts.

Threats

Threats to the eastern population come from loss of breeding habitat to hydroelectric power plant dams which inundate river breeding habitat. Mining and associated ship traffic near staging areas in Labrador and northeastern Quebec may also disrupt populations. Harlequin ducks are also vulnerable to oil spills and pollution. In Massachusetts, disturbance on wintering sites may have a negative influence. The closure of the hunting season for this species should be retained.

Conservation

Recent research involving placing satellite radios on males has revealed there are two distinct eastern Canada populations: the Eastern North American wintering population and the Greenland wintering population. Between 1997 and 2002, the eastern population estimate was only 1,575–1,800 birds, about three quarters of which winter in Maine. Annual mid-winter aerial surveys are no longer conducted, but monitoring continues with Audubon’s Christmas Bird Counts.

References

Bellrose, F. C. Ducks, Geese and Swans of North America. 2nd ed. Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Stackpole Books, 1976.

Contact

| Date published: | May 1, 2025 |

|---|