- Scientific name: Clangula hyemalis

- Species of Greatest Conservation Need (MA State Wildlife Action Plan)

Description

Long-tailed duck (Clangula hyemalis)

The long-tailed duck is a moderate-sized duck, differing from other ducks in that it has distinct winter and spring plumages as compared to the nuptial and eclipse plumages of other species. The males possess a long, attenuated tail in both plumages, while the females’ tails are more “duck-like.” Both sexes are more streamlined than other sea ducks. Males appear primarily white in their winter plumage, with a dark chest, back, wings, and tail. The face is tan with darker cheeks and throat. The color pattern is almost reversed in the summer, with the white head and neck changing to the dark brown color of the chest, and the tan of the face changing to white. The white plumage on the back also changes to a lighter brown. The contrast between the two plumages in the female is not as pronounced. The hen has a white chest and belly in the winter plumage and a mostly white head with light brown throat, back, and wings. In the summer, the brown darkens and the white face feathers are replaced by more shades of brown with smaller white patches. The males range from 40–47 cm (15.8–18.5 in) in length and weigh 650–1,100 g (22.9–38.8 oz). Adult females range from 38-43 cm (15–16.9 in) in length and typically weigh 500–950 g (17.6–33.5 oz).

Life cycle and behavior

As sea ducks, long-tailed ducks spend the majority of their time on the water. Long-tailed ducks consume mostly invertebrates like aquatic insects, zooplankton, and small crustaceans. They also eat plant matter and small fish. They can dive up to 60 m (200 ft) deep to access their food sources.

During mating season, males will defend a small pond or segment of a larger pond. After mating, the female will leave and build a nest alongside other females while males gather in molting areas. Females will lay 6–9 eggs annually. She will incubate the eggs for 24–29 days and raise the young alone.

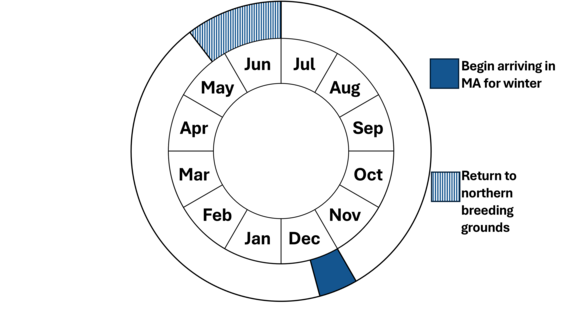

This graphic represents the peak timing of life events for long-tailed duck in Massachusetts. Variation may occur across individuals and their range.

Population status

Partners in Flight estimate the global long-tailed duck population to be slightly over 3 million.

Distribution and abundance

Long-tailed ducks are found in Massachusetts only during the winter, and then only along the coast. A few birds may be seen anywhere on coastal waters, but the largest concentrations of long-tailed ducks winter in Nantucket Sound. Flocks numbering in the tens of thousands roost in the sound overnight, then fly out to sea at dawn, returning at dusk. Because of this flight pattern, only a small portion of these ducks were counted on the annual Mid-winter Waterfowl Survey by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, which is no longer conducted. They are detected on Audubon’s Christmas Bird Counts.

Habitat

Long-tailed ducks feed offshore during the winter months spent in Massachusetts. They feed primarily on animal matter, including crustaceans, fishes, and mollusks. They are among the deepest diving ducks, reaching depths of 100 m (320 ft). Offshore shoals are important feeding sites.

Healthy habitats are vital for supporting native wildlife and plants. Explore habitats and learn about conservation and restoration in Massachusetts.

Threats

The open ocean habitats utilized by long-tailed ducks have historically made them immune to the hazards of development, but they could be disrupted by new offshore wind turbine development. Oil spills also present a threat as the birds are so concentrated at night. Disease outbreaks pose another hazard. Long-tailed ducks were the primary victims of a disease outbreak in Maryland in the 1980s. Because of their tendency to dive deep for food, many long-tailed ducks have been killed when entrapped in commercial gill netting operations. Effects from climate change on the ocean could harm long-tailed duck populations. The offshore habitat used by these ducks means scant hunting pressure is directed toward the species and only a few hundred are harvested each year in Massachusetts.

Plastic trash in the environment poses a threat as it can be mistaken as food by seabirds and shorebirds and ingested or cause entanglement. Ingested plastics, common for seabirds, can block digestive tracts, cause internal injuries, disrupt the endocrine system, and lead to death. Entanglement from fishing gear and other string-like plastics can cause mortality by strangulation and impairing movements.

Conservation

While no immediate monitoring or other actions are required at this time, tracking the diurnal activities of long-tailed ducks while wintering in Massachusetts, and determining the timing of their migration to and from Massachusetts coastal waters is advised. Audubon and USGS conducted a satellite telemetry study to gather information on nighttime roosting locations for the long-tailed duck in the Nantucket Sound, specifically Horseshoe Shoal, in the mid-2000s to assess the potential impact of an offshore windfarm development in the area. They discovered that the birds used large areas of the sound for roosting, and that the locations changed often. However, few birds used Horseshoe Shoal either for roosting or during the day. Thus, the proposed wind farm was not a direct threat to roosting long-tails. Additional research is needed to understand how climate change may affect the distribution of long-tailed ducks.

Avoid or recycle single-use plastics and promote and participate in beach cleanup efforts.

References

Allison, T.D., Perkins, S., and Perry, M. 2009. “Determining night-time distribution of long-tailed ducks using satellite telemetry.” U.S. Dept. of the Interior, Minerals Management Service, Herndon, VA. OCS Study MMS 2009-020. 22 pp.

Bellrose, F. C. Ducks, Geese and Swans of North America. 2nd ed. Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Stackpole Books, 1976.

Contact

| Date published: | May 1, 2025 |

|---|