Ice fishing and ice safety

Ice fishing is a great way to get outdoors in winter. Check out MassWildlife's guide for how-to videos, fishing techniques, and safety information.

Public hearings

Public hearings have been set for proposed deer and bear regulations. Click here to learn about the proposed changes, how to attend a hearing, and how to provide feedback.

Why you shouldn't feed wildlife this winter

Each winter, MassWildlife receives inquiries from the public regarding whether or not to feed wildlife. While people have good intentions, supplemental feeding of wildlife typically does more harm than good. Most wildlife seasonally change their behavior to adapt to cold temperatures and scarce food supplies. Supplemental feeding can alter that behavior and have detrimental, and sometimes fatal, effects. Wildlife in Massachusetts have adapted over thousands of years to cope with harsh winter weather, including deep snow, cold temperatures, and high winds.

Supplemental feed sites congregate wildlife into unnaturally high densities, which can:

- Attract predators and increase risk of death by wild predators or domestic pets;

- Spread diseases among wildlife or cause other health issues (e.g. Rumen acidosis in deer, Aflatoxicosis in turkeys);

- Cause aggression and competition over food, wasting vital energy reserves and potentially leading to injury or death;

- Reduce fat reserves, as wild animals use energy traveling to and from the feeding site;

- Cause wildlife to cross roads more frequently, therefore increasing vehicle collisions;

- Negatively impact vegetation and habitat in areas where feeding congregates animals.

Providing wildlife with food at any time of year teaches them to rely on humans for food, which puts them at a disadvantage for survival and can lead to human/wildlife conflicts. Once habituated behavior is established, it can be very difficult or impossible to change.

What can you do?

The best way to help wildlife make it through the winter is to step back and allow the animals’ instincts to take over. To help wildlife near your home, focus on improving the wildlife habitat on or near your property, by including natural food and cover (e.g., some conifer cover and regenerating forest or brushy habitat). It is also important that wildlife populations are in balance with what the habitat can support.

Bird feeding

MassWildlife biologists advise against feeding wildlife, including birds. Bird feeders may increase mortality from window strikes and predation by pet cats. Supplemental feeding also congregates wildlife into unnaturally high densities, which increases the risk of spreading diseases. Bird feeders often draw wildlife other than songbirds closer to homes, including bears, coyotes, wild turkeys, and rodents. As an alternative, consider using native plants and water to attract birds to your yard.

The legacy of a log

“If a tree falls in the forest and no one is around to hear it, does it really make a sound?”

While we may not have the answer to this age-old question, it’s clear that fallen trees make a big difference to wildlife whether someone hears it or not! This is especially true for trees that fall around brooks, streams, and rivers. Trees that grow close to water, like red maples, naturally fall into or across water over time. While it may look messy to people, dead wood in an ecosystem can create high-quality habitat conditions for both terrestrial and aquatic critters. Logs in moving water can slow down water flow, making pockets where nutrients can gather for algae and plants to grow and where fish can rest or stay cool while hiding from predators. Dead wood at the surface of water provides the perfect place for turtles to bask in the sun or for birds to perch and feed. Fallen logs spanning brooks, streams, and rivers create natural highways for wild animals of all sizes to cross and access more suitable habitat. “Tip ups”, or root structures that are exposed when a tree falls, are sometimes used by ground nesting bees and other invertebrates. Leaving fallen trees when there’s no risk to public safety can offer food, shelter, and habitat connectivity to all sorts of wildlife.

Retired science teacher, Michael V., captured the incredible influence of a fallen tree over a brook in MassWildlife’s Unkety Brook Wildlife Management Area in Dunstable. Watch the short video above to see who visited the log crossing over the last year!

Read next: Find out how wood in streams can benefit fish and aquatic ecosystems.

Video: The legacy of a log: Trail camera video at Unkety Brook WMA

Skip this video The legacy of a log: Trail camera video at Unkety Brook WMA.New England cottontail conservation

The New England cottontail, the only native rabbit in the region, thrives in dense young forests and shrublands. However, this habitat is disappearing across Massachusetts, Maine, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, Connecticut, and eastern New York, putting the species at risk. Young forests habitats are areas of dense clusters of tree saplings and sprouts that provide abundant food and shelter for a wide range of wildlife including New England cottontail.

MassWildlife, along with state and federal agencies, conservation groups, land trusts, universities, and private landowners, is working to preserve and create these vital habitats to bolster New England cottontail populations.

Through the New England Cottontail Technical Committee, partners conduct research, manage land, and raise awareness about the rabbit's challenges. The Technical Committee has set ambitious habitat goals for 2030, but achieving them depends on continued collaboration with private landowners to manage their properties to maintain young forest habitats. Within the cottontail’s range, over 75% of land is in private, land trust, conservation organization, municipal, or tribal ownership.

The young forest habitat on which the rabbits depend rapidly grows back into more mature trees that shade out the shrubs. After approximately 20 years, these growing forests no longer provide the essential cover from predators or buds and twigs for food. While it is no longer suitable for rabbits, these maturing trees become valuable habitat for other species. Therefore, young forest habitat must continually be created in different locations so rabbits and other wildlife that use it have a new place to call home.

Making progress in the Southern Berkshires

Across New England cottontail range, state biologists and other natural resource professionals work to benefit these rabbits by planning projects and connecting private landowners with financial resources and technical support. Since 2011, over 17,000 acres of habitat have been managed to benefit New England cottontails across the region on both private and public land.

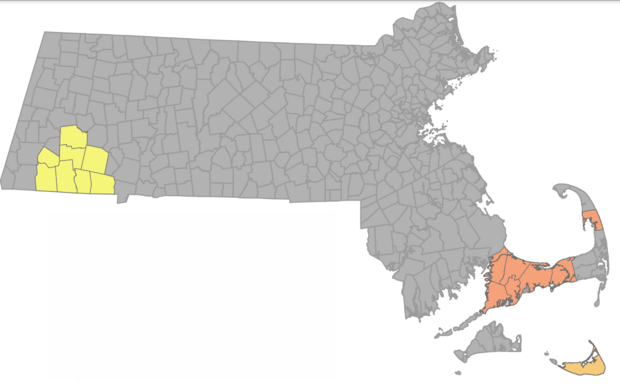

In Massachusetts, 30 landowners have conducted habitat projects on 700 acres, primarily in the Southern Berkshires. This area is home to one of Massachusetts’ few known populations of New England cottontail, with other populations on Cape Cod and Nantucket where thick areas of dense young trees and shrubs are more common. By creating patches of young forest, landowners in Granville, Tolland, Sandisfield, New Marlborough, Monterey, Otis, and Becket have made a significant contribution to the conservation effort!

New England cottontails, along with other native wildlife, are making homes in these managed habitats that are now about 10 years old. Young forest habitats provide optimal cottontail cover from about 10 and 15 years after creation, meaning new patches must be established nearby for the cottontails to survive, as they don’t travel far.

MassWildlife biologists monitor New England cottontails and engage with landowners in prime cottontail country. By linking landowners with financial and technical support, MassWildlife can help landowners plan habitat management activities that bolster cottontail and other native wildlife that thrive in young forest areas.

Landowners living in New England cottontail range can contact Marianne Piché (marianne.piche@mass.gov) to learn about options for habitat creation on their property.

Did you know? A wide variety of wildlife rely on the dense cover and abundant food provided by young forest habitats—American woodcock, ruffed grouse, white-throated sparrow, wood turtles, bobcats, and a variety of pollinating insects, to name just a few!

Click here to learn more about New England cottontail conservation and the importance of young forests.

Protecting habitats: 2,500 acres in 2024

Land acquisition staff from the Department of Fish and Game (DFG) and MassWildlife collaborated on 26 projects during the last fiscal year (July 1, 2023 – June 30, 2024) protecting nearly 2,500 acres of forests, grasslands, water frontage, and inland water access points. This brings the total amount of land under the care and control of MassWildlife to over 237,000 acres. Land acquisition projects were completed for a total cost of just under $3.5M. Most funding for land acquisition comes from bond capital, with the remaining portion provided by the Wildlands Fund, generated by a $5 fee added to each purchase of a hunting, fishing, or trapping license.

The land acquisition team focuses on properties which provide or improve public access for fishing, hunting, wildlife viewing, and other nature-based recreation. Protecting these lands improves climate resiliency by protecting forests and wetlands that absorb carbon dioxide and floodwaters in extreme weather events. Additionally, connecting large tracts of habitat allows plants and animals to adapt to changing climate conditions. By acquiring land, we conserve the rich biodiversity of Massachusetts by protecting habitats of rare and common species.

MassWildlife often works with conservation partners to help facilitate land protection projects, and this year was no exception. Special thanks go to Essex County Greenbelt Association, Mt. Grace Land Trust, and Franklin Land Trust.

Types of MassWildlife properties:

- Wildlife Management Areas (WMA) are owned by MassWildlife and are open to all for hunting, fishing, trapping, and other outdoor recreation.

- Wildlife Conservation Easements (WCE) are privately owned land where MassWildlife owns the development and recreation rights. These lands are open to all for hunting, fishing, trapping, and other outdoor recreation.

Land acquisition highlights by district

- Northeast District: Over 72 acres along Unkety Brook in Dunstable were protected and will become part of Unkety Brook WMA. The parcel provides important habitat for rare and common wildlife and has beautiful woodland with views of Unkety Brook and surrounding marshes. Much of the property is open to hunting. Eighteen acres in West Newbury were added to Crane Pond WMA, and 21 acres of salt marsh in Salisbury were protected which will simplify and enable marsh restoration activities in the area.

- Southeast District: A 25-acre inholding within Copicut WMA was protected and is now part of the large assemblage of conserved lands known as the Southeastern Massachusetts Bioreserve. The parcel, which is open to hunting, contains mixed upland forest and small grassy fields and provides important forest core habitat for both common and rare wildlife. A 15-acre parcel was protected in Mashpee and will become part of the Santuit Pond Wildlife Conservation Easement.

- Central District: Acreage was added to 5 existing WMAs and 1 new property, Templeton Brook WMA, was formed. The former Templeton Development Center property officially became part of Norcross Hill WMA increasing the size from 500 acres to approximately 2,000 acres.

- Connecticut Valley District: Williamsburg WMA has nearly doubled in size after the addition of 110 acres. The acquisition dramatically improves fishing access to the East Branch of the Mill River and protects sensitive streamside habitats and wildlife travel corridors. The new 14-acre Tekoa Narrows Wildlife Conservation Easement protects sensitive species and provides public access to the Westfield River.

- Western District: One hundred huntable acres were added to Green River WMA including beautiful, forested slopes and 1,000 feet of frontage along the Green River. The 130-acre Edge Hill Wildlife Conservation Easement, an abandoned golf course, was created and brings new opportunities for restoration and recreation.

Land acquisitions by town

| Town(s) | District | Property name | Acres |

|---|---|---|---|

| Douglas | Central | Mine Brook WMA | 20.33 |

| Hardwick | Central | Muddy Brook WMA | 38.31 |

| Lancaster | Central | Bolton Flats WMA | 34.10 |

| Petersham | Central | Popple Camp WMA | 93.00 |

| Templeton | Central | Templeton Brook WMA | 83.03 |

| Templeton,Phillipston,Royalston | Central | Norcross Hill WMA | 1,386.64 |

| Monson | Connecticut Valley | Wales WMA | 27.25 |

| Northfield | Connecticut Valley | Satan's Kingdom WMA | 12.90 |

| Westfield | Connecticut Valley | Tekoa Narrows WCE | 13.99 |

| Whately | Connecticut Valley | Mt. Esther WMA | 12.02 |

| Whately | Connecticut Valley | Great Swamp WMA | 75.00 |

| Williamsburg | Connecticut Valley | Williamsburg WMA | 110.00 |

| Dunstable | Northeast | Unkety Brook WMA | 72.50 |

| Salisbury | Northeast | Salisbury Salt Marsh WMA | 21.00 |

| West Newbury | Northeast | Crane Pond WMA | 18.04 |

| Fall River | Southeast | Copicut WMA | 25.00 |

| Mashpee | Southeast | Santuit Pond WCE | 15.24 |

| Ashfield | Western | Edge Hill WCE | 132.78 |

| Becket | Western | Shales Brook WMA | 73.71 |

| Chester | Western | Hiram H. Fox WMA | 50.00 |

| Egremont | Western | Karner Brook WMA | 17.18 |

| Savoy | Western | Savoy WMA | 4.10 |

| Williamstown | Western | Green River WMA | 100.00 |

| Windsor | Western | Savoy WMA | 41.75 |

| Total | 2477.87 |

Contact

Online

| Date published: | January 7, 2025 |

|---|