- Scientific name: Alces alces

- Species of Greatest Conservation Need (MA State Wildlife Action Plan)

Description

Moose (Alces alces)

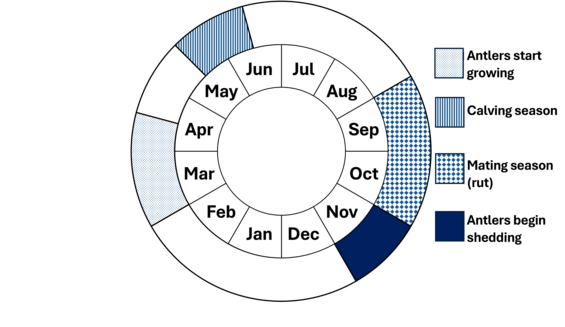

Alces alces americana, also known as the eastern moose, is the subspecies found in Massachusetts. They are the largest extant member of the deer family and are dark brown with lighter-colored legs and high-humped shoulders. Adult moose weight ranges from 270 to over 455 kg (600 to over 1,000 lb) for bulls (males) and 225–320 kg (500–700 lb) for cows (females). They can stand up to 182 cm (6 ft) tall at the shoulders and have long legs that are up to 122 cm (4 ft) in length, which allow them to walk in deep snow. Moose have a distinctive flap of skin that protrudes beneath their lower jaw called a bell, which is more pronounced in adult bulls than in cows or immature bulls. Normally only bulls grow antlers, which begin growing in March to early April and are fully grown by August when the velvet is shed. The bulls begin shedding their antlers in November after the breeding season has concluded.

Life cycle and behavior

Moose are most active at dawn and dusk. Moose lack upper incisors and so they strip off leafy browse and bark rather than snipping it off neatly. This will leave a similar rough browse line as white-tailed deer, but it will be up to 2.5m (8 ft) off the ground. Moose eat large amounts of leaves, twigs, and buds, as well as sodium-rich aquatic vegetation in the summer. Willows, aspens, maples, oaks, fir, and viburnums are their preferred foods. Winter food mostly consists of buds and twigs, needle-bearing trees, and hardwood bark. A healthy adult moose can eat 18–27 kg (40–60 lb) of browse daily.

The breeding season for moose runs from September to October. Cow moose breed at 2 or 3 years of age. In mid-May they give birth to 1 to 2 calves weighing 9–11 kg (20–25 lb). Moose offspring stay close to their mother after birth, and she will actively protect their calves against predators. Increased moose activity also occurs in April and May when the adult cow drives off her young of the past year before she calves.

This graphic represents the peak timing of life events for moose in Massachusetts. Variation may occur across individuals and their range.

Population status

Population and range expansion peaked around 2004, and the population currently appears stable at around 800–1,000 moose in the state.

Distribution and abundance

Moose have reclaimed most of their historic range in Massachusetts. Today, moose are mostly found in areas of western and central Massachusetts, with occasional sightings in eastern towns particularly in the Worcester hills. The moose density in Massachusetts is very low in comparison to more northern states like Maine, New Hampshire, and Vermont. Future trends are difficult to predict, but moose trends in nearby states are declining mostly due to winter tick-related mortality.

Habitat

Land areas recently logged or disturbed by fire, wind events, or beavers provide excellent moose habitat as these sites contain new plant growth. Moose are mostly found in these forested habitats, but in the summer, moose tend to seek food and relief from flies and mosquitoes by spending time in wetlands.

ealthy habitats are vital for supporting native wildlife and plants. Explore habitats and learn about conservation and restoration in Massachusetts.

Threats

Because of their large size and strength, adult moose have very few natural predators, which explains their general lack of fear of humans and bold behavior. However, young, sick, or injured moose can succumb to predation by black bears or coyotes. In Massachusetts, most moose die from vehicle collisions, accidents in the wild (drowning, falls, etc.), disease, starvation, and old age. In recent years, winter tick, brain-worm (a tiny parasite carried by white-tailed deer), liver flukes, and a combination of stressors have become significant factors for moose populations. Climate change has increased the risk for winter moose mortalities and summer droughts have forced moose to move more on the landscape to access water.

Conservation

Monitoring for moose in Massachusetts is presently done through passive data collection of moose-vehicle collisions, sightings by hunters, and large animal responses. MassWildlife is currently conducting regular disease surveillance for brain-worm through the collection of heads from moose that have died in vehicle collisions.

Moose hunting is statutorily prohibited in Massachusetts. The primary management related actions are currently related to public messaging about reducing moose-vehicle collisions. This includes targeted deployment of electronic signage with MassDOT during high-risk seasons along high-risk roads and highways. There is also regular coordination with the Massachusetts Environmental Police to haze moose out of suburban areas where there is increased risk to both the moose and the public. Occasionally moose that have ventured into urban areas and are unable to find their way out are chemically immobilized by the Massachusetts Large Animal Response Team and moved to proper habitat to ensure public safety.

More formal research is needed to better understand the impact of winter ticks on moose populations locally and their land use, particularly at the suburban-exurban interface.

References

Geist, V. Moose. Pages 223-254 in Deer of the World, Their Evolution, Behavior, and Ecology. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 1998.

Karns, P.D. Population Density and Trends. Pages 125- 140 in F.W. Franzmann and C.C. Schwartz (eds.), Ecology and Management of the North American Moose. Washington and London: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1997.

McDonald, J.E. “The moose question.” Massachusetts Wildlife. 50(2000): 24-35.

Vecellio, G.M., R D. Deblinger, and J.E. Cardoza. “Status and management of moose in Massachusetts.” Alces 29(1993): 1-7.

Wattles, D.W. “Status, movements and habitat use of Moose in Massachusetts.” M.S. thesis, University of Massachusetts, Amherst, Massachusetts. 2011.

Wattles, D.W. “The effect of thermoregulation and roads on the movements and habitat selection of Moose in Massachusetts.” Doctoral dissertation, University of Massachusetts, Amherst, Massachusetts. 2014.

Wattles, D.W., and S. DeStefano. “Space use and movements of Moose in Massachusetts: implications for conservation of large mammals in a fragmented environment.” Alces 49(2013): 65-81.

For more information on moose from MassWildlife, see Learn about moose.

Contact

| Date published: | May 1, 2025 |

|---|