- Scientific name: Colinus virginiana

Species of Greatest Conservation Need (MA State Wildlife Action Plan)

Description

Northern bobwhite

Northern bobwhite is a small to medium-sized quail, averaging about 20-25 cm (8-10 in) long. Males are slightly heavier than females. The tail is rounded and contains 12 retrices. Adult males have brown uppers, barred with tan and black, a white forehead and triangular patch on throat and chin. The breast, sides, and flanks are barred with black and some chestnut. Adult females are similar but with buff areas on the head instead of white.

Life cycle and behavior

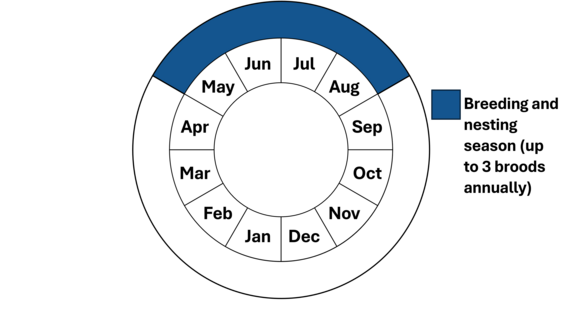

Phenology in Massachusetts. This is a simplification of the annual life cycle. Timing exhibited by individuals in a population varies, so adjacent life stages generally overlap each other at their starts and ends.

Northern bobwhites prefer to walk or run on the ground but are capable of quick bursts of flight. Northern bobwhites primarily eat seeds and plant material. They will also consume insects, especially during the breeding season. They will feed in flocks (i.e., coveys) year-round but may be on their own during breeding season.

During the late spring and summer nesting season, the male and female select a site and build a nest together. Northern bobwhite nests are located on the ground, often placed in a shallow depression among dense growth. Many will form an arch of grasses and weeds above the nest to hide it from potential predators. The hen will lay 12-16 eggs, which will be incubated by both the male and female. Eggs will hatch 22-24 days later and the chicks are immediately mobile.

Population status

Bobwhite quail are extremely limited in their distribution, inhabiting portions of Cape Cod and some coastal areas in southeastern portions of the Commonwealth. Additionally, quail are commonly stocked as a popular gamebird and for dog training purposes, consequently quail are commonly found statewide. It is likely those quail found statewide have very poor survival after being released.

Distribution and abundance

Historically in Massachusetts, Northern bobwhite probably occupied coastal areas and possibly up some of the major eastern river systems, as well. However, after significant land use change associated with colonial settlement, these quail were likely distributed nearly statewide. Their peak abundance occurred during the extensive land clearing in the 1820s to 1840s, when upwards of 80% of Massachusetts was in some form of agricultural production. Several very severe winters greatly reduced this statewide distribution of quail. Severe winter storms between the 1870s and 1898 wiped out all quail between Cape Cod and New Hampshire. After another severe winter in 1903-04, quail may have greatly reduced statewide but quickly rebounded in southeastern Massachusetts where winters were milder and plenty of suitable agricultural and brushy habitat existed. By the 1960s, rapid development and “cleaner”, more efficient farming practices were greatly altering the availability of suitable habitat for quail, and consequently populations began to plummet. At present, quail breed regularly only in Barnstable, Dukes, and Nantucket counties (and possibly in Plymouth and Bristol). Significant numbers of farm-raised quail are introduced/stocked each year across the state for hunting and dog training purposes, but none of these stockings have yielded viably reproducing quail populations.

Habitat

Northern bobwhites require early successional habitats among a wide variety of vegetation types. These include small agricultural fields with brushy hedgerows, small warm-season species dominated grasslands or pastures, oak/pine savannahs with shrub and herbaceous ground cover, and mixed areas of grass and brushlands. The best habitats include a mosaic of small patches of field, forest, and crop lands which are protected from habitat succession by grazing, burning, or active management. In all cases, because quail are a ground feeding bird, they need open space on the ground to forage for insects, seeds, and fruits, but close access to brushy escape cover to avoid predation.

Healthy habitats are vital for supporting native wildlife and plants. Explore habitats and learn about conservation and restoration in Massachusetts.

Threats

Northern bobwhite populations have been declining for 40 years. These losses are principally attributed to loss and alteration of early successional, grassland, and, most importantly, agricultural habitats at both the local and landscape level. Severe winter storms have greatly affected bobwhite distribution in the past, and will likely do so into the future, as quail in Massachusetts exist at the extreme northern boundary of the geographic range. The consequence of increased development has not only greatly influenced available habitat but also has indirectly led to increased predator levels. Often, populations of skunks, raccoon, and opossums are higher in developed areas. These nest predators can be devastating to quail nesting and production. Other predator populations including fox, fisher, weasel, and birds of prey can impact adult quail and their chicks.

Conservation

Quail continue to be detected during large-scale breeding bird surveys such as the Audubon Breeding Bird Atlas and Christmas Bird Count and through citizen-driven efforts such as e-Bird. Although relatively uncommon, breeding populations exist primarily across coastal areas in the southeastern part of the state. Managing landscapes for quail is extremely important for their long-term sustainability but has become increasingly difficult as large areas of open space are being fragmented and developed or otherwise converted and developed. Prescribed fire can be an important tool for managing quail habitat. MassWildlife and other state and NGO partners regularly conduct prescribed burns in portions of existing quail range each year, but it is likely that the size and scale of prescribed burning alone will not entirely satisfy the habitat requirements for quail. Additionally, increased predators associated with development (e.g., raccoon, skunk, opossum) are likely impacting and regulating quail numbers. It is likely that quail currently exist in areas that have relatively stable habitat composition, again primarily found in coastal areas.

References

Brennan, L.A. “Northern bobwhite (Colinus virginianus)”. In The Birds of North America, No. 397. (A. Poole and F. Gill, eds.) The Birds of North America, Inc., Philadelphia, Pa., (1999): 28pp.

Guthery, F.S., M.J. Peterson, and R.R. George. “Viability of northern bobwhite populations.” Journal of Wildlife Management 64 (2000): 646-662.

Williams, C.K., F.S. Guthery, R.D. Applegate, and M.J. Peterson. “The northern bobwhite decline: scaling our management for the twenty-first century.” Wildlife Society Bulletin 32 (2004): 861-869.

Contact

| Date published: | April 4, 2025 |

|---|