- Scientific name: Antigone canadensis

- Species of Greatest Conservation Need (MA State Wildlife Action Plan)

Description

Sandhill crane (Antigone canadensis)

Sandhill cranes are large wading birds with a heavy body, long neck, and long legs and are found in open grassland and wetland habitat. Males and females have an identical plumage; they stand about one meter (~3.3 ft) in height and have a wingspan of approximately two meters (~6.5 ft). They are omnivorous birds that mate for life, are long-lived (the oldest was at least 36 years), and have low reproductive rates. They have an elaborate and graceful courtship dance and produce an impressive, loud rattling call that can be heard for miles and was described by Aldo Leopold (“father of wildlife management”) in his best-selling book A Sand County Almanac as a “trumpet in the orchestra of evolution.”

Life cycle and behavior

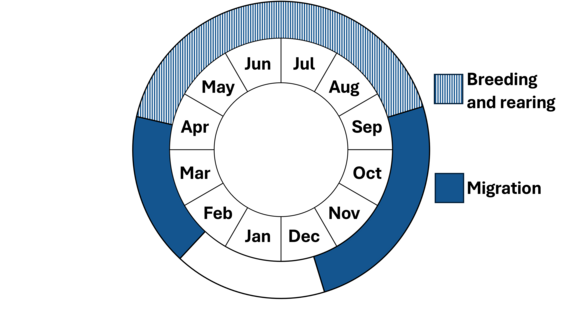

Phenology in Massachusetts. This is a simplification of the annual life cycle. Timing exhibited by individuals in a population varies, so adjacent life stages generally overlap each other at their starts and ends.

Sandhill cranes spend the winter in the southern United States or northern Mexico, with many going to Texas. They are an early spring migrant, with peak migration occurring through March. In Massachusetts they return to their breeding areas by late March or early April. The clutch size is 1-3 eggs (typically 2) for sandhill cranes, and they lay a single egg every two days. Although females do the majority of incubation, both sexes develop a brood patch and share incubation duties. The incubation period lasts for 29-32 days, and young are precocial and leave the nest within 24 hours of hatching. Brooding responsibilities are primarily completed by the female, and young chicks may take refuge on her back or under her wing. Both adults will feed the young chicks. Chicks start to feed on their own once they are about half the size of the adults, and fledging occurs around seven weeks after hatching. The family remains together through their late fall migration, and independence doesn’t typically occur until the birds' first spring migration. Sandhill cranes typically begin breeding at 2-3 years old.

Population status

The sandhill crane population crashed in the early 20th century due to extensive loss and degradation of wetland habitat coupled with unregulated hunting. The population was so reduced that only approximately 25 breeding pairs remained of the eastern subspecies (breeding throughout the Great Lakes region), known as the greater sandhill crane. However, protective legislation (e.g., Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918) and wetland protection set the stage for a resurgence of the species. Since the North American Breeding Bird Atlas was established in 1966, sandhill cranes have displayed a remarkable 5% annual rate of increase.

Distribution and abundance

The sandhill crane range includes New England, the upper Midwest, much of Canada, Alaska, and isolated populations in the western United States. In addition to the migratory populations, there are a few subspecies that consist of resident populations in the southeastern United States, including Florida and Mississippi. With an increase in numbers, there has been a concomitant range expansion that has resulted in nesting cranes in Ohio, Pennsylvania, New York, and many of the New England states.

Whether or not they historically nested in Massachusetts, the sandhill crane is now a breeding bird of the Commonwealth. The crane expansion in Massachusetts was first documented when a single crane was reported in New Marlborough throughout the summer of 2004 and a pair turned up the following year. The first nesting attempt in Massachusetts was documented at this site in 2007 and resulted in the pair successfully fledging a chick. Since that time the cranes have been returning each year to the wetlands and fields of New Marlborough, and the number of pairs and nesting locations has gradually increased. However, the state population is vulnerable due to the very low number of territorial pairs and limited nesting habitat. It is due to those reasons that the sandhill crane is included as a species of greatest conservation need in Massachusetts.

Sandhill crane (Antigone canadensis)

Habitat

Sandhill cranes are most commonly found in areas where wetlands are adjacent to areas of large grasslands. Cranes typically nest within a wetland and build a mound-style nest constructed from marsh vegetation, mud, and sticks. The birds will forage in both the wetland and grassland habitats. Cranes are found in open habitats like grasslands and agricultural fields during migration.

Healthy habitats are vital for supporting native wildlife and plants. Explore habitats and learn about conservation and restoration in Massachusetts.

Threats

Sandhill crane (Antigone canadensis)

As a ground nesting bird, sandhill cranes are vulnerable to nest predation as well as human disturbance around the nest site. Additional threats include loss and degradation of nesting habitat and collisions with artificial structures. As sandhill cranes may congregate in high numbers during the winter and migratory periods, the species also is vulnerable to diseases like the highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI).

Conservation

Protection of nesting habitat is important for the conservation of sandhill cranes in Massachusetts. Wetland habitat restoration efforts could enhance nesting habitat in some areas. Protecting important wintering grounds and migratory stopover habitat would support the full annual cycle conservation of the species.

References

Gerber, B. D., J. F. Dwyer, S. A. Nesbitt, R. C. Drewien, C. D. Littlefield, T. C. Tacha, and P. A. Vohs (2020). Sandhill crane (Antigone canadensis), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (A. F. Poole, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA.

Sauer, J.R., J.E. Hines, J.E. Fallon, K.L. Pardieck, D.J. Ziolkowski, Jr., and W.A. Link. 2022. The North American Breeding Bird Survey, Results and Analysis 1966 – 2022. Laurel, MD.

Walsh, J., and W.R. Petersen. 2013. Massachusetts Breeding Bird Atlas 2. Massachusetts Audubon Society and Scott & Nix, Inc.

Contact

| Date published: | April 22, 2025 |

|---|