- Scientific name: Lepus americanus

- Species of Greatest Conservation Need (MA State Wildlife Action Plan)

Description

Snowshoe hare (Lepus americanus) in white pelage

The snowshoe hare is the largest native lagomorph in New England. They are also one of the few mammals in Massachusetts that change their fur color seasonally. In the summer, snowshoe hares have dark brown fur on their body with white fur on their belly. In the winter, they have white fur, sometimes mottled with brown. They have black eyelids, black tipped ears, and large hind feet with well furred soles. Snowshoe hares are typically 38–52 cm (15–20.5 in) long, including a 2.5–5.7 cm (1–2.25 in) tail, and weigh between 907–1406 g (2–3.1 lb).

Life cycle and behavior

Snowshoe hare are herbivores. They eat grasses, buds, twigs, and leaves in the summer and rely on twigs, bark, and buds in the winter. They also ingest some of their own droppings, called cecotropes, to absorb as much nutrients as possible from their plant-based diet. Snowshoe hares are solitary but may have overlapping home ranges with other individuals. They’re mostly active at dawn, dusk, and at night but may be seen on days with low light.

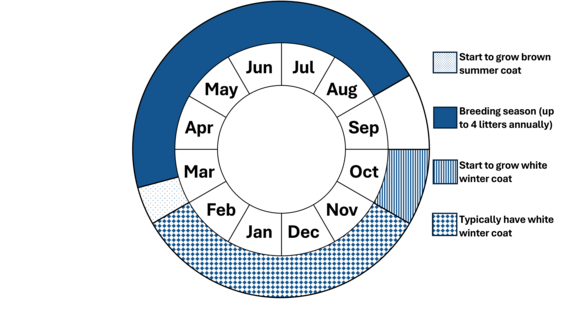

Snowshoe hare breeding season is from March through August. After a 36-day gestation period, 1–8 (2–4 on average) young, called leverets, are born. Unlike rabbits, leverets are born with their eyes open and covered in a thin layer of fur. The leverets are weaned and disperse four weeks later and will become sexually mature at 1 year old. Female snowshoe hares can produce up to 4 litters per year. Approximately 85% of young snowshoe hares do not make it past their 1st year.

This graphic represents the peak timing of life events for snowshoe hare in Massachusetts. Variation may occur across individuals and their range.

Population status

Snowshoe hare exist within relatively low population densities across the state. They are most abundant in areas with varied types of young forest and early successional habitats.

Distribution and abundance

Historically, snowshoe hare were likely limited to areas of Berkshire, Franklin, and northern Worcester counties in places where winter snowfall was highest. However, intentional stockings for hunting purposes have greatly altered that historic distribution. Although stocking of snowshoe hare ceased in the mid-1990s, they continue to be found more or less statewide, including areas of southeastern Massachusetts, Cape Cod, and even Nantucket. Abundance is still likely highest in those historic areas as that is where habitat and snowfall contribute to higher hare survival. Hare have very prominent population cycles that consist of extreme population explosions followed by collapse. These population cycles are driven by a combination of predatory-prey dynamics and impacts to vegetation caused by excessive overbrowsing by hare during population peaks.

Habitat

Snowshoe hare utilize open fields, fencerows, swamps, riverside thickets, cedar bogs, and coniferous lowlands. They can often be found in areas with dense thickets, overgrown fields, and brush that provide essential shelter, food, and protection from predators. They thrive in areas of varied young forest and early successional habitats and wetland bogs and swamps.

Healthy habitats are vital for supporting native wildlife and plants. Explore habitats and learn about conservation and restoration in Massachusetts.

Threats

The most significant threat to snowshoe hare in Massachusetts is the relatively low abundance of preferred young forest and other early successional brushy habitats. The lack of suitable habitat is typically a function of reduced natural disturbances, less timber harvesting, and generally widespread development and fragmentation of open space.

The effects of climate change, and most notably a decline in the amount and coverage of winter snowfall, may impact snowshoe hare survival. While some hares have adapted and remain brown all winter long, many continue to turn white in the winter and thus are potentially more vulnerable to predators during snowless periods.

Conservation

While no direct survey or monitoring exists for snowshoe hare in Massachusetts, they are infrequently detected during periodic surveys for New England cottontail. However, those surveys are not statewide, so they do not adequately demonstrate abundance or distribution except that hare have been and continue to be detected in portions of the state that seem inconsistent with their historical range.

MassWildlife is active in managing a variety of early successional and young forest habitats that are required by snowshoe hare including young forest and other early successional habitats found in forested areas of the state. MassWildlife collaborates with private landowners to manage habitat through partnerships and programs within the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) Farm Bill. MassWildlife also often consults and promotes early successional and young forest management beneficial to hare and numerous other species with other conservation organizations and public landowners across the state.

Better information on specific snowshoe hare distribution, habitat use and preference, and factors that affect survival will be important to continue to ensure that hare persist on the landscape in Massachusetts.

References

Gigliotti, L.C, E.S. Boyd, and D.R. Diefenbach. “Atypical Winter Coat Coloration of Snowshoe Hares Near the Southern Extent of Their Range.” Ecosphere 16, no. 3 (2025): e70217

Zimova, M., L. S. Mills, and J. J. Nowak. “High Fitness Costs of Climate Change-Induced Camouflage Mismatch.” Ecology Letters 19 (2016): 299–307.

Contact

| Date published: | May 1, 2025 |

|---|