- Scientific name: Bubo scandiacus

- Species of Greatest Conservation Need (MA State Wildlife Action Plan)

Description

Snowy owl (Bubo scandiacus)

The snowy owl is a large owl that breeds in the Artic tundra where its white plumage blends in with the environment. Males are smaller and whiter than females that on average have feathers with more brown barring. Young males have a female type plumage and do not attain their nearly all white coloration for several years. Snowy owls have yellow eyes, and their vocalizations are varied from low repeated hoots, barks, and screams. These owls can be active during both day and night.

Life cycle and behavior

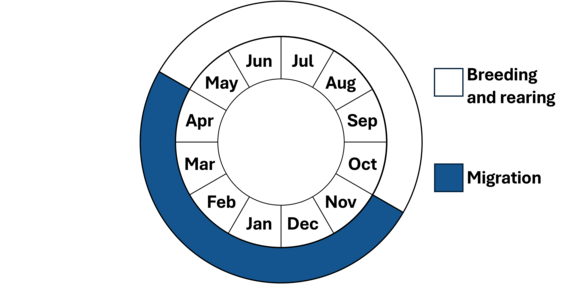

Phenology in Massachusetts. This is a simplification of the annual life cycle. Timing exhibited by individuals in a population varies, so adjacent life stages generally overlap each other at their starts and ends.

In the Arctic, the owls largely forage on lemmings and other small mammals. However, it is an opportunistic predator that will prey on birds as large as sea ducks like eiders. Snowy owls are ground nesters that are single brooded. Nesting is often linked to prey availability on the breeding grounds with birds laying up to 14-16 eggs (most large clutches range between 5-10 eggs) in a single nest when lemmings are abundant but foregoing nesting or laying smaller clutches (4-7 eggs) when prey are scarce. Some birds remain on or near their breeding territory throughout the year while others migrate south to areas across southern Canada and northern United States. The species is known as an irruptive migrant, and the numbers of individuals moving south in the winter can vary dramatically among years.

Little is known about the life span of the snowy owl due to few long-term wintering or breeding studies on the species, although individuals are known to live for over 20 years in the wild. The longevity record for a wild snowy owl comes from a female banded in Massachusetts and later recaptured in Montana was determined to be at least 24 years old.

Population status

Due to the species' nomadic habits, it has been challenging for biologists to provide a global population estimate for the species. In the early 2000s, Birdlife International estimated the entire population to include 290,000 individuals, but in 2013 Partners in Flight estimated 200,000 birds globally, including 100,000 in North America. However, more recently, an international team of researchers conducted a broad review and status assessment and revised the global estimate putting it between 14,000-28,000 breeding adults. The drop in the global population estimate is both a result of prior estimates being biased high with birds being more sparsely distributed than previously thought and a decline in the overall population (>30% over last three generations, 1996-2020). The snowy owl is classified as vulnerable by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN).

Distribution and abundance

The breeding range for the snowy owl is circumpolar and extends throughout the Arctic including areas of North America, Europe, and Asia. During the nonbreeding period, in North America some birds move south of the Arctic to spend the winter in areas of Canada and the northern United States. Snowy owls regularly winter in Massachusetts, although their numbers in the state can vary dramatically annually. In boom years when high numbers of chicks are produced, many young birds typically move south in search of food. Snowy owls wintering in Massachusetts are typically found in grassland habitat near the coast that resembles their Arctic nesting habitat. Logan Airport in Boston can host some of the highest densities of snowy owls in the country.

Snowy Owl (Bubo scandiacus)

Habitat

Snowy owl breeding habitat is located in the Arctic tundra and can occur wherever there is abundant prey. Typical habitat is in open areas with grasses, dwarf shrubs, and lichens and occur at elevations below 300 meters. Wintering habitat includes breeding habitat and areas resembling breeding habitat including farmlands, rangelands, coastal dunes and marshes, islands, and other open habitats.

Healthy habitats are vital for supporting native wildlife and plants. Explore habitats and learn about conservation and restoration in Massachusetts.

Threats

Snowy owls face many threats throughout their annual cycle. Historically the species was hunted and persecuted by humans. The native people of the Arctic would hunt adults and collect eggs for food, although this subsistence hunting is greatly reduced today. In the late 1800s and extending into the early 1900s, these owls were regularly shot on their wintering grounds in southern Canada and the United States.

Current threats to the species include a warming climate as its breeding habitat is particularly vulnerable to rising temperatures, although more study is needed to better understand the impacts of climate change on the species. Where the species exists in developed areas on the wintering grounds, birds may be threatened by rodenticide poisoning. Because these owls are often active during the day, they have become a popular attraction to bird watchers and wildlife photographers. When people consistently approach birds too closely causing them to flush repeatedly, it can result is excessive disturbance to the individuals and threaten their ability to survive. Over the last few years, a new threat has emerged, and numerous snowy owls have died from infection with highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI). The owls are disproportionately impacted by the virus as they may prey upon sick birds or forage on infected carcasses. Another threat to snowy owls is collision with aircraft as many birds are attracted to the habitat on airfields. At Logan Airport there has been a long-standing effort by Mass Audubon to trap and translocate snowy owls away from the airport to promote both aircraft safety and owl conservation.

Rodenticides (e.g., Second Generation Anticoagulant Rodenticides - SGARs) move up food chains and pose a threat to raptors when they consume prey that have ingested these chemicals. As a result, SGARs have been found in a high percentage of raptors that have been tested for them in Massachusetts, and it is well documented that they can kill individual raptors. However, their population-level impacts on raptors remain largely unknown.

Conservation

Conservation actions to benefit snowy owls in Massachusetts include protecting roosting sites from human disturbance. Continuing to relocate these birds away from airfields remains an important action to conserve the species in Massachusetts. Further investigation of the threats to snowy owls on the breeding grounds is important in developing full annual cycle conservation strategies for the species.

Conduct research to better understand the impacts of highly toxic rodenticides (e.g., SGARs) to raptor populations. Promote an integrated pest management approach that emphasizes the use of alternative pest control measures whenever possible to reduce negative impacts to wildlife. Coordinate with other state agencies to improve tracking and reporting of rodenticides found in wildlife and develop outreach materials for the public.

References

Holt, D. W., Matt D. Larson, N. E. Smith, D. L. Evans, and D. F. Parmelee (2020). Snowy Owl (Bubo scandiacus), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (S. M. Billerman, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA.

Lanyon, W.E. “Eastern Towhee (Pipilo erythrophthalmus).” 1995. The Birds of North America, No. 262 (A. Poole and F. Gill, eds.). The Birds of North America, Inc., Philadelphia, PA.

McCabe RA, Aarvak T, Aebischer A, Bates K, Bety J, Bollache L, Brinker D, Driscoll C, Elliot KH, Fitzgerald G, Fuller M, Gauthier G, Gilg O, Gousy-Leblanc M, Holt D, Jacobsen KO, Johnson D, Kulikova O, Lang J, Lecomte N, McClure C, McDonald T, Menyushina I, Miller E, Morozov VV, Øien IJ, Robillard A, Rolek B, Sittler B, Smith N, Sokolov A, Sokolova N, Solheim R, Soloviev M, Stoffel M, Weidensaul S, Wiebe KL, Zazelenchuck D, Therrien JF (2024). Status assessment and conservation priorities for a circumpolar raptor: the Snowy Owl Bubo scandiacus. Bird Conservation International, 34, e41, 1–11

Veit, R., and W.R. Petersen. Birds of Massachusetts. Lincoln, MA: Massachusetts Audubon Society, 1993.

Contact

| Date published: | April 22, 2025 |

|---|