- Scientific name: Catostomus commersonii

- Species of Greatest Conservation Need (MA State Wildlife Action Plan)

Description

White Sucker (Catostomus commersonii)

The white sucker is known for its elongated body and characteristic inferior mouth that is positioned downward to facilitate feeding off the bottom. Specifically, this species has a rounded snout that barely projects beyond the upper lip when viewed from below and its lower lip contains a deep median notch. Its lower lip is often about twice as large as its upper lip. During the spawning season, reproducing males develop large tubercles (protruding bumps) on their caudal and anal fins that are used for territory defense during reproduction. Large specimens may reach lengths of 760 mm (30 inches), but most adults are less than 600 mm (24 inches) long.

While coloration varies slightly depending on the waterbody and season, juveniles and some adults have three or more irregular lateral blotches found on their sides. They often are olive brown with a dark dorsal surface, have dark-edged scales, and clear or slightly darkened fins. Breeding males will develop a gold dorsal surface and a scarlet or black colored stripe along their sides during the spring spawning season.

Life cycle and behavior

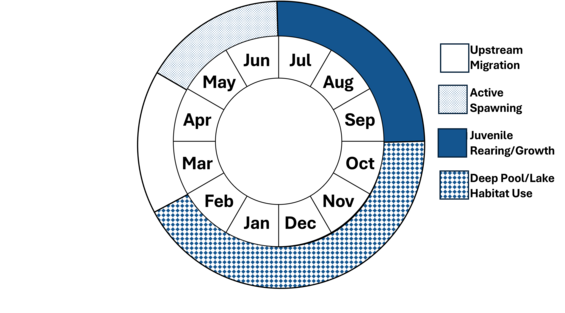

This species is considered a lithophilic spawner that seeks out gravel and rock for spawning habitat. Spawning takes place in mid-April to May during periods of high flow in Massachusetts when adults move upstream into tributaries or main river shoals containing shallow gravel substrate. Young-of-the-year grow quickly and may reach upwards of 114 mm (4.5 inches) in total length by the end of their first summer. Adults live up to 10 years and reach sexual maturity by 3-5 years. This species is a generalist benthic feeder that readily consumes invertebrates and fish eggs found on the bottom. During feeding, this species can identify different food types and expel unwanted diet items like detritus or plant material. White sucker eggs are often consumed by other fish species creating important energy transfer and foraging opportunities for multiple species. Additionally, individuals are readily captured by avian predators like bald eagle and osprey, linking important aquatic resources to terrestrial biota.

Population status

The population status of this species is unknown but is captured during standard fish surveys in streams and rivers through its distribution in the state. While no population estimates are available, essential habitat for these species has declined likely also resulting in population declines.

Distribution and abundance

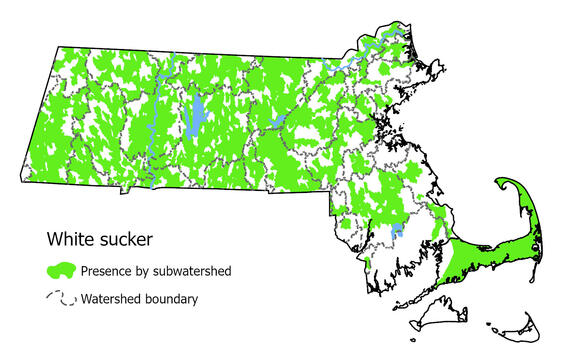

In North America this native species has a wide range spanning from northern Canada all the way south to Tennessee and can be found as far west as the Pacific drainage slope. In Massachusetts, they are found in virtually every drainage except for Martha's Vineyard, Nantucket, and several of the smaller mainland coastal streams. While this species may have a wide distribution throughout the state, highly abundant populations historically found in ideal habitats have declined or dispersed within connecting systems due to habitat losses.

Data from 1999-2024 from annual surveys.

Habitat

White suckers gather in the shallows to spawn over gravel and rock.

The white sucker is considered a cool water fluvial-dependent species typically found in the riverine habitat class and is present in gently sloping rivers and streams even in steep rivers. Larger rivers often contain adult populations, while juveniles are more readily captured in smaller streams. During the spawning season this species moves upstream into tributaries containing moderate flow, clear water, and rock and gravel for spawning. It can also be found within the lacustrine habitat class in nearshore areas in shallow drainage lakes. In this case, the fish mostly uses tributary rivers or streams for spawning and rearing and then adults use the lake for growth. This species prefers aquatic habitats that contain submergent aquatic vegetation throughout the year and can be found foraging in slow moving water like pools or breaks in the current. Deep pools or tributary junctions with a connection to groundwater are important for both summer and winter refugia from the coldest or warmest temperatures.

Healthy habitats are vital for supporting native wildlife and plants. Explore habitats and learn about conservation and restoration in Massachusetts.

Threats

Seasonal warming associated with climate change is likely affecting the timing of reproduction, habitat usage, and could be negatively impacting this cool water species. Increases in water temperatures and decreases in precipitation during the summertime can reduce available habitat for this species to forage, thermal moderation, and avoid predation. These impacts are exacerbated in streams that are heavily altered by water supply withdrawal. Extreme flow events during the spring can impact the availability of spawning habitat by covering gravel and rock with fine sediment, resulting in reduced reproductive outputs. Climate change will also enhance the variability in stream flows, reducing rearing and growth habitat in drought and flood alike. Additionally, more direct threats like dams can cause sedimentation and decreases in aquatic connectivity, impacting movement to spawning grounds and the quality of these habitats. This species is considered relatively tolerant to pollution but is sensitive to ammonia and chlorine in heavily wastewater-surcharged large rivers.

Survey and monitoring

Efforts to document this species and their abundance are conducted during fish community assessments and is successful at capturing individuals in multiple locations in the state. This species is often encountered using fish passage at dams to move upstream on larger rivers like the Connecticut River.

Management

Management on this species focuses on river and stream restorations, improving habitat and connectivity through actions such as dam removal, culvert replacement, and reconnecting streams to their floodplains. These actions help remediate the effects of 300 years of channelization in Massachusetts and help restore access and habitat quality of spawning tributaries, as well as providing deep bend pools that are used for summertime and winter refugia during times of low water or adverse water temperatures.

Research needs

A better understanding of the movements of this species could help update their range in the state and identify important habitat connectivity supporting this native species. Specific research on sedimentation processes in areas of urbanization and agriculture could help protect and manage important gravel and rocky spawning grounds necessary for this species to reproduce.

References

Hartel, K.E., Halliwell, D.B., Launer, A.E. Inland Fishes of Massachusetts. Lincoln, MA: Massachusetts Audubon Society, 2002.

Page, L.M., Burr, B.M. Peterson Field Guide to Freshwater Fishes of North America North of Mexico. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 2011.

Contact

| Date published: | April 10, 2025 |

|---|