- Division of Fisheries and Wildlife

Media Contact

Media Contact, MassWildlife

Grassland restoration offers a range of benefits that extend far beyond aesthetics. These restored grasslands, rich with native grasses and wildflowers, provide essential breeding and foraging grounds for pollinators, ground-nesting birds, and other native wildlife. Restored habitats require less intensive management and help control invasive species naturally. Keep reading to find out how MassWildlife restored these habitats and how they contribute to healthier ecosystems across the state.

What are warm-season grasslands?

Warm-season grasslands are treeless or nearly treeless areas that are dominated by native perennial bunch grasses such as little bluestem, Indian grass, switchgrass, and big bluestem. They are often rich with wildflowers such as common milkweed, butterfly-weed, wild bergamot, and countless others. Warm-season grasslands are best maintained by periodic fires, a practice that stimulates native plants and discourages many invasive species.

Why are agricultural fields being restored to warm-season grasslands?

These native grasslands provide important habitat for numerous plants and animals. Native grasses provide structure for nesting, rearing, and hunting. Sometimes they are called “bunch grasses” because they grow in distinct clumps with space between individuals and form an “umbrella” of the leaves above. The space of bare ground provides nesting areas for ground nesting bees, beetles, and other insects. Pollinators benefit greatly from the improved wildflower diversity found in warm-season grasslands.

One of the most important groups of species that benefit from the restoration efforts are grassland birds. Species such as grasshopper sparrow, upland sandpiper, bobolinks, American kestrel, and prairie warbler all depend on open grasslands for all or part of their lifecycle. For example, grasshopper sparrows eat, sleep, and nest on the ground, running between the clumps of grass while hunting for insects. It is also great wild turkey poult rearing habitat. The baby turkeys can hunt for insects moving between the clumps of grass with overhead cover, which keeps them out of sight of birds of prey. The improved cover provided by warm-season grasses is also preferred by pheasants. In the taller grasses, pheasants tend to stay on site, and many hunters prefer this experience.

How does MassWildlife restore a native grassland?

MassWildlife manages many former agricultural properties. Some may continue to be leased to farmers for hay or corn production, but for others, the leases are not renewed and MassWildlife staff maintains the open fields through regular mowing. Restoration of native species improves the habitat for native wildlife, while reducing the need for mowing. Some sites, like Katama Plains WMA or Montague Plains WMA, have already established native grasslands that only need fire to maintain and improve the composition, but they are the exception. Most sites dominated by non-native plants, and the restoration process typically begins with herbicide treatment to kill the invasive species, especially targeting the thick cool-season grasses. In recently farmed areas, herbicide may not be needed. Then, the site is burned to eliminate the thatch. Usually, the burned ground is harrowed next to create a seed bed. Then, the native seed is planted. Seed spreaders, or drills are used to plant the seed, however MassWildlife staff invented their own method using a sewer pipe and a backpack blower. Different seed mixes are used depending on the soil characteristics of the site. Some include wildflowers and a mix of grasses, while others are little bluestem alone. The seeds are always a local native genotype. Sometimes the seeds are purchased from a nursery, but other times they are harvested by MassWildlife staff using a specialized attachment on a tractor. The harvested seed is not only hyperlocal, but it also contains a diverse mix of seeds typical in native grasslands. After two or so years of growth, the site is ready to be burned again. Fire promotes growth of the native plants and helps discourage undesirable competition. During early restoration, sites are burned annually. Once well-established, they are burned every 1–3 years.

Where are grassland restoration projects taking place?

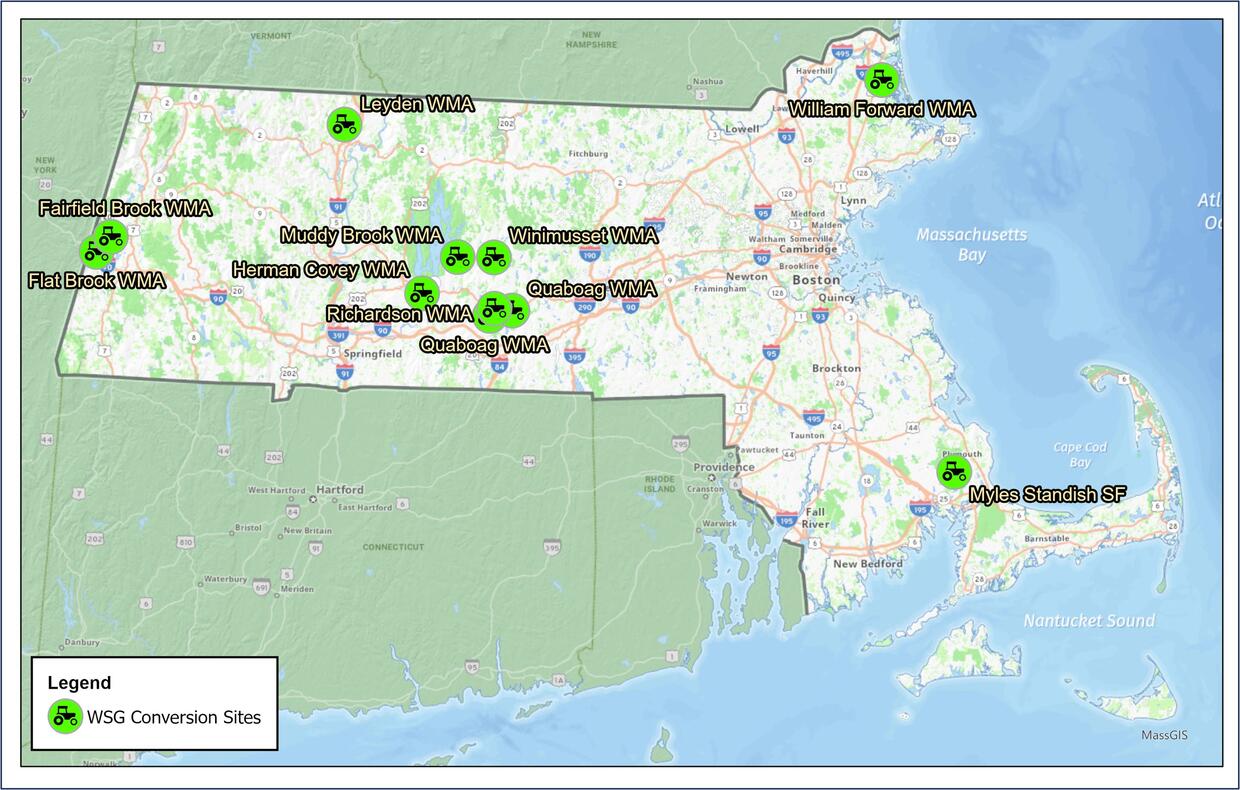

The largest grasslands at Frances Crane WMA (Falmouth) and Southwick WMA (Southwick) have been the targets of large-scale restoration for many years. Bolton Flats WMA (Bolton and Lancaster) is another larger grassland, but it seeded naturally in an abandoned gravel mine. These three large grasslands total around 750 acres. In the last four years or so, MassWildlife has begun the restoration process on many smaller grasslands as well. Currently, there is around 475 acres of grassland restoration projects across the state, as seen in the map below.