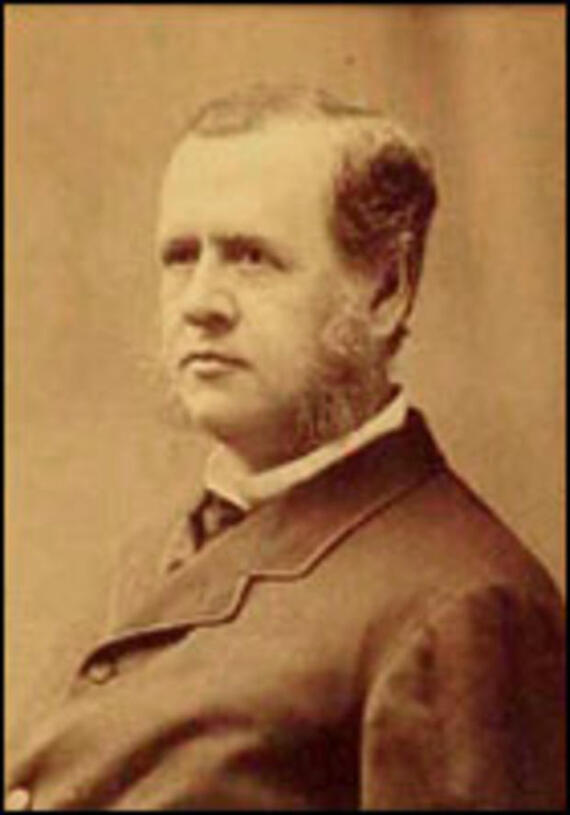

Dwight Foster

Associate Justice memorial

137 Mass. 597 (1884)

The Honorable Dwight Foster, a justice of this court from the thirty-first day of August, 1866, to the twelfth day of January, 1869, died at his residence in Boston on the eighteenth day of April, 1884. A meeting of the members of the bar of the Commonwealth was held in Boston on the twenty-first day of April, at which resolutions were passed, which were presented to the full court on the eighth day of May. Before presenting them, the Attorney General addressed the court as follows:

May it please your Honors: I have been requested by the bar of the Commonwealth to call the attention of the court to the death of the Honorable Dwight Foster, formerly one of the justices of this court, which occurred at his home in the city of Boston on the eighteenth day of April last, and to present the resolutions, which have been unanimously adopted, as an expression of their respect for and appreciation of the character of the deceased. He was born in Worcester on the thirteenth day of December, 1828, graduated at Yale College in 1848, and was admitted to the bar the following year. In 1860, he was elected Attorney General, at the early age of thirty-two, and held the office for four years. In 1860, he was appointed by Governor Bullock an associate justice of this court, which position he resigned three years later. Governor Andrew, who had an opportunity to know and appreciate Attorney General Foster during the difficult and trying times of the Rebellion, addressed him as follows: "I beg to congratulate you on the successful termination of this delicate and difficult litigation, and on the patience, discretion, and skill with which it has been conducted by you to so successful an issue. Please to accept this acknowledgment of my official and personal appreciation of your conduct of this case, as, indeed, of all the business of the office of Attorney General during the whole term of your service."

On another occasion the Governor wrote to him as follows:

"I have received, with a most grateful sense of its indulgent and generous expression toward myself, your note bidding farewell to the official relation which, for four eventful years, has united us in the administration of the executive department of the Commonwealth. The separation has been looked forward to by me with keen regret, and I feel no less its consummation. On your serenity, clearness, firmness, and intelligent judgment, both as a lawyer and friend, I have relied with the utmost confidence. Your advice, while always healing and pacific, has been always true-headed and manly. The more public professional efforts you have made, as well as the general conduct of your department, have all added new honors to an office heretofore filled by able men, some of them of unsurpassed capacity and fame. Returning word for word your friendly expressions, and looking to a better future for our country than ever its past has been, -- trusting, too, that we both may feel we have served her faithfully and zealously in whatever place we may stand, -- I am your obliged friend and obedient servant."

Judge Foster had no struggles with poverty while climbing the rugged paths of learning, but in name, ancestry, wealth, and social position he had all that heart could desire, and he appreciated and improved these advantages, graduating with the highest honors of his class. He was thoroughly equipped and qualified for the duties of his chosen profession. He was conscious of his own ability, and had confidence in himself. He did much to simplify and reform the criminal law, to avoid its technicalities, that it should be a protection to the innocent rather than a shield to the guilty. The death of such a man, half-way in the journey of life, is a great loss to the profession and the Commonwealth. His was a happy, active, useful, and eventful life, and, notwithstanding his serious and alarming illness during the winter, he was unwilling to give up his work. His last appearance and argument before your Honors, a few weeks ago, exhibited the courage and character of the man. Although emaciated and suffering from physical weakness, he argued his cause with clearness and great ability.1 You saw the great lawyer, with eye and intellect undimmed, eloquently pleading and heroically struggling against disease and physical exhaustion. He has left an example worthy of imitation, and we may be consoled by his peaceful death. At night he closed his eyes and went quietly to sleep.

"And then the dark-brow'd mother, Death, bent down her face to his, and he was born to Him."

The Attorney General then presented the following resolutions:

Resolved, That we have received with sorrow the announcement of the decease of the Hon. Dwight Foster, formerly a justice of the Supreme Judicial Court of the Commonwealth, who died at Boston, April 18, 1884, in the fifty-sixth year of his age.

By this event the Commonwealth has lost a distinguished citizen, the bar an accomplished leader and associate, and the community an adviser of eminent learning and ability.

Called to the Supreme Bench at in early age, he exhibited the highest qualities as a jurist. His opinions are models of English. He gave clear expression to the doctrines of the law, with a terseness and facility which showed his perfect apprehension of the principles of the science. Especially in the great departments of equity and commercial law, his thorough knowledge of men and affairs, gained by an extensive practice, his sound legal instinct and strong sense of justice, enabled him to give direction to the course of jurisprudence, and to form the law in those branches in which it is most susceptible of growth, and therein to do the highest work and best service of a good judge. By his early retirement from the bench, this court lost a most valuable associate and distinguished ornament.

In personal character, he was remarkable for independence and courage. He was above the reach of prejudice, and his opinions, broadly formed and strongly held, were forcibly and fearlessly as well as courteously expressed.

In his home and social relations he was generous, kindly, hospitable, and affectionate, and his loss is felt by his family and a large circle of acquaintances and friends to be irreparable.

Resolved, That the Attorney General be requested to present these resolutions, and to ask that they be entered upon the records of the Supreme Judicial Court.

Causten Browne, Esq, then addressed the court as follows:

May it please the Court: In the presence of the members of this court and of the gentlemen of the bar who are assembled here, it would be unbecoming in one whose professional intercourse with our brother Foster was as limited as my own to undertake to contribute to the record of the abilities and accomplishments which he displayed upon the bench and in his practice at the bar; but I should like to say a few words, a very few, in regard to some personal qualities in him which, during a good many years of friendly intercourse, always interested me, and, as time went on, commanded my increasing admiration, respect, and regard. I think that the nature of the mental and moral constitution of our friend was not altogether obvious; did not lie quite open to the common eye, so that he who ran might read. It was rather one which required and repaid attentive observation. It was not difficult to misunderstand and misjudge him. We may even say, that it was not his habit -- perhaps not as much so as it ought to have been -- to concern himself as to whether he was rightly understood and judged or not. Certainly he courted no man's favorable judgment; if it came to him, it was to come as his lawful due, not as the capture of a chase.

One thing which we readily remarked about our brother Foster was his easy command of all his faculties. There was no vehemence in his vigor; there was no bustle in his activity. He did not exhaust himself. He gave one, I think, very strongly the impression of having power in reserve, -- not only power of thought, but power of will. His thought and his will applied themselves to their object without apparent effort. Again, he was an uncommonly steady man under fire. He received it, we should say, not so much with firmness as with composure and cheerfulness. He seemed to be a man who would be ready for an emergency; a man not easily taken by surprise; whose faculties would come when they were called; a man of that precise combination of pluck, nerve, and self-command which make up what is called 'two-o'clock-in-the-morning courage."

Our brother Foster's judgment of men and of things, and of his own duty, was formed with singular independence and maintained with singular tenacity; not to be confounded, I think, with that stubbornness which is proof against argument; rather the intelligent tenacity of one who, having taken up a position because his judgment approves, does not surrender it until his own better judgment disapproves. He was not a hard man to reason with; but he was a very hard man to drive, or to scare, or to wheedle.

The characteristics I have mentioned, if there should be nothing added, might suggest a character more or less unamiable. Such certainly was not our brother Foster's. His independence was of that manly sort which respects independence in others. His self-reliance was without any unpleasant mixture of self-assertion. It was not restless, or pushing, but sober and dignified, as determined by self-respect and by clearness of understanding. In controversy, he was a straight and a hard hitter; but he was candid, patient, good-tempered, and courteous. Whether he was a man to make friends readily, I doubt; but that he held hard to the friends he did make, we well know. It was not in Dwight Foster to turn his back upon a friend, any more than to turn his back upon an enemy.

These are the impressions which he produced upon us among whom his professional and social life was mainly passed; but I believe it may be said that the best wine of his companionship was kept for his own home. Of how few men can we say that! And is it not high praise? Is it not the guinea stamp? It was in that home that, only fifty-five years of age, with everything in the world to live for, in the conscious possession of intellectual faculties at their very best, our friend sat down, in the midst of those whom he loved best in the world, to wait for death. During the many long days of pain and nights of restlessness, there was no impatience or repining. He was as calm and as cheerful as ever, enjoying the society of his family thoroughly, considerate of others, absolute master of himself, while all the time he watched the slowly moving shadow of the approaching end. It seems to me, sir, that nothing can exceed the pathos of that scene, unless it be its dignity.

George O. Shattuck, Esq., addressed the court as follows:

May it please your Honors: After the very warm tributes which have been paid to the memory of Judge Foster in his native city, there is very little left to be said. I shall confine myself to one or two characteristics of the man as we saw him after he came to Boston. When he came here, twenty years ago, he had already won a high place at the bar. He had proved himself equal to the demands of the office of the Attorney General, at the early age of thirty-two, in the most eventful and trying years in the history of the Commonwealth. He brought here to Boston a splendid civil courage and self-reliance which are sure to come to a man who is well born, when, with large opportunities, he has found his mental and moral powers equal to any emergency. From that day to the end of his life, he maintained a sturdy independence. He formed his opinions and expressed them with but little reference to those who were about him. He was not a man of such an active temperament that he was leader on common occasions; but, when the front rank was demoralized, he was capable of bringing up the reserve with steadiness and power. I know of no better illustration of this than his connection with the case of Lowell v. Boston.2 After the great fire, the Legislature passed an act authorizing the city of Boston to borrow $20,000,000, and lend it to the sufferers to aid them in rebuilding. All the sympathy of the community was in favor of the act. The leaders of opinion within the bar and outside of it supported it. But Judge Foster made up his mind that it was wrong. Singlehanded, with no backing except a few names, he entered upon the controversy. He argued the case against the ablest counsel the city of Boston could employ, and won it. The act was declared unconstitutional. No man to-day would question the wisdom of his judgment, or fail to recognize the value of his public services in that case. Judge Foster, although he was independent, and although he was never narrowed by any social influences, did not lack sympathy, and was never arrogant. Whether on the bench or off it, his manners were always courteous. There was nothing small or narrow in his methods of thinking, or in the judgments which he formed.

Before I sit down, I may be permitted to speak of one who has just left us, one among the few who were sent by the bar to pay the last offices of respect to Judge Foster. I refer to one who bore an honored name, -- a name, I may say, more honored and loved by the bar than any other in this Commonwealth.3 His life may remind us that not all success at the bar comes in its contests. If the value of his life is to be measured by the confidence which was felt in his sound judgment and integrity, by his fidelity to every trust, by the affection which all who were near him felt for him, it can be truly said that he worthily bore the name with which he was honored. No higher praise than that can be accorded.

Chief Justice Morton responded as follows:

Brethren of the Bar: Your full and just tributes to the memory of Judge Foster leave but little for us to add, except to declare our hearty concurrence in the sentiments of respect and regard for him expressed by you in your resolutions.

His life has been one of uninterrupted success and usefulness. He graduated at Yale College with the highest honors of his class. Those who remember him at the Law School of Harvard College speak of his great ability, and of the remarkable maturity of his powers, which made him, though one of the youngest, conspicuous among his fellow students.

He entered into practice in Worcester county, in competition with a bar noted for its ability and learning, and in a very short time gained a high standing.

At the early age of thirty-two years he was elected Attorney General of the Commonwealth, and held this office for four successive years, to the satisfaction of the people and with honor to himself. His experience as Attorney General led him to propose and procure the passage of the act of 1864, properly entitled, "An act to promote public justice in criminal cases;" a measure of reform which has proved just and beneficial in the administration of the criminal law, preventing in numerous cases the defeat of public justice by objections to complaints or indictments in no way affecting the merits, but purely technical and formal.

In 1866, he was appointed a justice of this court; a position for which he was well qualified by his native ability, by his extensive and accurate learning, and by his self-controlled and well-balanced character. It is a remarkable fact, that he was the fourth Judge Foster in a direct line of descent. His great-grandfather, Jedediah Foster, was one of the justices of the Superior Court of Judicature after the Revolution, and before the adoption of the Constitution; his grandfather and his father both served the Commonwealth as judges of probate, as well as in other high official trusts.

It was the cause of deep regret to the court and the public that he felt compelled to resign his place upon the bench after a short service of less than three years. Since he left the bench his life has been spent in your midst, filled with important and useful labors. It is not necessary that we should multiply words of praise; the achievements of his life are his highest praise; the record which he has left is his proudest monument.

He died in the full maturity of his powers, before age had dimmed his mental faculties, transmitting to his children with added lustre a name which has been held in high honor since the birth of our Commonwealth.

The death of such a man, upright, able, learned, independent, fearless, hospitable, and generous, is a public calamity. It is fitting that we with whom he was so closely associated should take suitable notice of it. Concurring in the sentiments you express in your resolutions, we cordially accede to your request, and order that they, together with a memorandum of these proceedings, be entered upon the records of the court.

The court then adjourned.

Footnotes

- The case of Attorney General v. Whitney, ante, 450.

- Reported 111 Mass. 454.

- Lemuel Shaw, Esq., a son of the late Chief Justice, died in Boston on May 6, 1884.