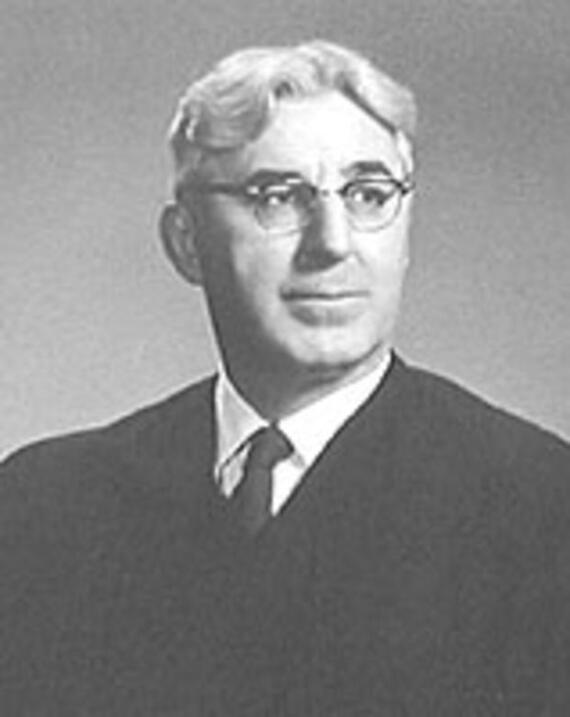

Francis J. Quirico

Associate Justice memorial

433 Mass. 1303

A special sitting of the Supreme Judicial Court was held at Boston on December 19, 2000, at which a Memorial to the late Justice Francis J. Quirico was presented.

Present: Chief Justice Marshall; Justices Abrams, Greaney, Ireland, Spina, Cowin, and Sosman; retired Justices Benjamin Kaplan, Joseph R. Nolan, and Francis P. O'Connor; and former Justice Charles Fried.

Thomas F. Reilly, Attorney General, addressed the court as follows:

May it please the court: As the Attorney General of Massachusetts, it is my honor to present, on behalf of the Commonwealth, a memorial and tribute to the late Francis J. Quirico. Justice Quirico served this court with great distinction from 1969 to 1981. He also served for thirteen years as a justice of the Superior Court. He was a model trial and appellate judge: patient and prepared; humble and humane; decisive and determined to do equal justice under the law.

Justice Quirico reached his high station from humble roots. His parents emigrated from Italy in 1905 and settled in Pittsfield. Francis Quirico was born in Pittsfield on February 18, 1911. He attended schools there and worked in his father's carpentry shop. He graduated from Pittsfield High School in 1928. He then graduated with highest honors from Northeastern University Law School in 1932. He supported himself during law school with work in a cabinet-making shop in Boston, applying the skills learned from his father and continuing his lifelong interest in furniture-making.

He practiced law in Pittsfield and served in World War II in the United States Army Air Corps, rising to the rank of Captain. He returned to Pittsfield and his law practice after the war. He served as solicitor for the city of Pittsfield from 1948 to 1952 and as president of the Berkshire County Bar Association.

Former Chief Justice Hennessey has noted the love that Justice Quirico had for his native city and region. He loved its beauty and its history. He knew the key role that the people of Berkshire County had played in the Massachusetts Constitution of 1780. He often reminded his colleagues of the Berkshire Remonstrance and other actions of the people of that county that led to the adoption of our State Constitution.

Governor Herter appointed Francis Quirico to the Superior Court in 1956. There he earned a reputation as an extraordinary trial judge. Former Justice Paul Reardon summarized his work on the trial court in these words:

"In his charges to the jury, his disposition of complicated motions, his fairness, his objectivity, his handling of the courtroom and in his logical conclusions, Justice Quirico was an obvious standout."

These skills led to his assignment as judge in two of the most difficult cases ever tried in the Commonwealth. The story of Justice Quirico's role in these cases was well told by Deirdre Harris Robbins, Gael Mahony, and Michael Keating in the Western New England Law Review in 1980. Justice Quirico sat on the so-called Small Loans trials, which ran from 1964 through 1967. These trials were the longest in the history of the Commonwealth. The trials concerned bribes paid by small loan companies to public officials. Justice Quirico ruled on hundreds of motions in the cases. His findings, rulings, and decisions in the cases covered 1,400 pages. As his law clerk, Michael Keating, put it, his conduct of the trial "preserved order in what otherwise might have been chaos." On appeal, the defendants made 700 claims of error. This court issued a 188-page opinion. It found no error -- not one -- and affirmed.

Justice Quirico also sat on the so-called Boston Common Garage trials. These cases involved larceny and conspiracy concerning the construction of a parking garage under the Boston Common. These complex trials lasted several weeks each. Both trials led to appeals to this court. Again, this court affirmed Justice Quirico in every respect.

The trials of these complex cases show not only Justice Quirico's skill but also his work ethic. His close friend Justice Paul Tamburello described Justice Quirico's "relentless pursuit of his work." As was said about another Attorney General, Rufus Choate, Francis Quirico seemed to think that the vacation of a lawyer or judge is the time between the question put to a witness and his answer. Former Chief Justice Edward Hennessey tells the story of how two defendants in a Pittsfield court, pleading guilty to breaking and entering a Pittsfield court house, complained that, on the night of the break, they had to wait until midnight for Justice Quirico to turn out the light in his office and go home.

Another former Chief Justice, Arthur Rugg, whose portrait hangs in this courtroom, seemed to have Justice Quirico in mind when he said the following:

"The competition for prizes in the legal profession is sharp and severe. Many must fail. Only those can hope to win conspicuous success who possess peculiar aptitude and large natural endowments combined with well directed and ceaseless work, . . . unflagging courage and unblemished character."

Francis Quirico had all of these traits and more.

Yet he remained a modest man. Former Justice Reardon praised his "modest spirit" -- "an exemplar of what a judicial gentleman can and should be." The Berkshire Eagle quoted former Judge Clement Ferris as follows:

"He never said a disparaging word about a fellow attorney or fellow judge; he never used language inappropriate to a gentleman, never spoke out of impatience, stress or anger." Justice Reardon said: "While others have jockeyed for preferment, he . . . moved ahead on his own merit, the best argument for his advancement being his own excellence." Thus for Justice Quirico, as for others of modest spirit, "the path of duty was the way to glory."

Justice Quirico's gentle nature showed in cases that reminded us of our imperfect natures. According to the Berkshire Eagle, Superior Court Judge Quirico, a lifelong bachelor, was asked to decide whether a man's proposal of marriage constitutes an oral contract that permitted a woman to keep the engagement ring. Judge Quirico wrote:

"What was said at that occasion may forever remain the secret of the parties. Perhaps this is as it should be and perhaps it is best that inquisitive lawyers and courts should neither pry into the thoughts of a lady and a gentleman at such a climatic moment, nor should such thoughts and words be spread upon the records of the court."

His ruling was overturned but no one can doubt the humanity that lay beneath his reasoning. Governor Francis Sargent appointed Justice Quirico to the Supreme Judicial Court in 1969, to replace Justice Arthur Whittemore. He was the first American of Italian descent to sit on the court. He first sat with the court for oral argument on December 1, 1969. His first published opinion was in MacGibbon v. Board of Appeals of Duxbury, a zoning case.

His tenure spanned a decade in which the court confronted many large public questions. During these years, the court addressed the death penalty, abortion rights, and school prayer, to name only a few. Justice Abrams, who retires this month, and other justices present here today served the court with great distinction during these challenging years. Justice Quirico, perhaps more than any other justice, was aware that the 1970's had led the court to new ground: cases filled with claims that the acts of co-equal branches of government -- the policymaking branches -- had violated the State or Federal Constitution. During this decade, Justice Quirico voiced special concern for the separation of powers and the role of the judiciary in our democratic system. Justice Greaney has stated that Justice Quirico's opinions show "an acute awareness of the separation of powers" and a justice "sensitive to the fact that the Legislature reflects the public mood to a much greater extent than the judiciary."

Deirdre Harris Robbins has detailed the majority opinions and dissents in which Justice Quirico set forth his philosophy of judicial restraint. Perhaps the most ringing dissent came near the end of his tenure in District Attorney for the Suffolk District v. Watson, a case concerning the constitutionality of the death penalty. He wrote:

"In relying on its view of contemporary morality, the court proceeds with no apparent regard for the constitutionally distinct roles of the judiciary and the Legislature . . . .

"I believe that we should not so alter the principles of judicial restraint and the constitutional requirement of separation of powers under Article 30 of the Declaration of Rights . . . according to the nature of the subject matter of the legislation being construed . . . ."

In this passage Justice Quirico invoked the Article that includes perhaps the most famous phrase in our Constitution of 1780: "to the end that it be a government of laws and not of men." In an earlier case involving veterans' preferences, Justice Quirico in dissent stated that the court "must be ever mindful that judicial inquiry does not extend to the expediency, wisdom, or necessity of the legislative judgment, for that is a function that rests entirely with the law-making department."

Despite Justice Quirico's usual deference to legislative action, he joined with other members of the court when he thought that a statute violated a clear constitutional principle. His last opinion was for the court in Moe v. Secretary of Administration and Finance, in which the court struck down a State law that denied State Medicaid funds for women seeking abortions. This ruling for a divided court was an appropriate marker for an important decade in the development of constitutional law.

Justice Quirico retired from the court at the constitutionally mandated age of 70. He later served as a recall judge in the Superior Court. In his retirement he was able to spend more time with his beloved family and friends in Pittsfield. He continued to give time and financial support to many programs supporting the youth and the poor of Berkshire County.

Justice Quirico died on October 11, 1999. The Massachusetts Senate adjourned in his memory on October 14 of that year. He was survived by his brother John and sisters Eugenia and Virginia of Pittsfield. Their great respect for their brother and the court led them to donate his papers to the Supreme Judicial Court Historical Society, where they join an oral history by Justice Quirico.

Today we gather here in Boston but our thoughts drift west to the Berkshires. We think of Herman Melville, at his home in Pittsfield, staring out at Mount Greylock, the mountain large and daunting in the twilight. We think of the lawyers and judges of Berkshire County, and all the citizens of our great Commonwealth, gazing up at the monument of public service that is the legacy of Francis Quirico. If we are daunted, we are also inspired --inspired by the example of this model judge and gentle man.

On behalf of the Commonwealth, I respectfully move that this Memorial be spread on the records of the Supreme Judicial Court.

Michael B. Keating, Esquire, addressed the court as follows:

Chief Justice Marshall and Honorable Members of the Supreme Judicial Court; may it please the court. It is my privilege to speak on behalf of Justice Quirico's colleagues in the practice of law: for the men and women who knew him as fellow attorney, a member of the judiciary, and a friend. It is a special honor for all of us to support the Attorney General's motion.

I leave to others this morning the task of describing Justice Quirico's intellectual strengths, his legendary grasp of the law, and the breadth and significance of his decisions. I would prefer to speak of a person whose gentle spirit produced the warmth, kindness, and humility which permeated all aspects of his life, both personally and professionally. Although he will be remembered for his profound insights into our laws and institutions, his greatest gift was to his fellow man whom he found a source of endless fascination and object of his unlimited affection. It was Justice Quirico's humanity, above all else, which distinguished his life.

Justice Quirico never lost touch with the Lakewood neighborhood of Pittsfield, where he was born and where he continued to reside with his two sisters, Virginia and Eugenia, until his death. Although professionally he had moved to where we assemble this morning, personally he stayed well grounded in that community throughout his life. His acts of charity and kindnesses to his neighbors were continuous and remarkable. When his mother told him that a newcomer to the community -- a lonely immigrant from Italy without prospects for employment -- had lost his place to live, Judge Quirico purchased a place for him to live throughout his life and, as if that was not enough, gave him a dog to keep him company. And at this time of the year each year, Justice Quirico took the man out for a traditional Italian holiday dinner to ease the loneliness of the holidays. His humility and common decency and his accessibility to everyone, without regard to station, made him loved and respected by everyone in his community. By everyone's account, he was never known to say an unkind or disparaging word about anyone. Upon learning of his death, the mayor of Pittsfield, Remo Del Gallo, summed it up rather well: "What a good man," he said. "What a good man," he was indeed.

One might ask what prompted this modest man from an even more modest background to aspire to be a lawyer? The short answer is that it apparently never occurred to him. Like all graduates of Pittsfield High School in 1928 he was headed for work at General Electric until one morning, much to the consternation of his mother, a probation officer appeared at his house and told young Francis that he was to be taken immediately to the school superintendent's office. The superintendent, who had been told by the high school principal that this young man had unusual promise, employed him briefly until he decided that he should be a lawyer and shipped him off to Northeastern University Law School. As the Attorney General has noted, he supported himself in law school by working as a cabinetmaker -- his father's occupation -- and graduated with highest honors in 1932 in the teeth of the Depression. He opened a law office, quite briefly -- in Boston where, he later reported, his only visitors were his landlord and other starving lawyers. Therefore, he returned to his beloved Pittsfield.

One personal trait of Justice Quirico that undoubtedly emerged in his early days as a practicing lawyer was his encyclopedic knowledge of everything around him, particularly historical information. If you asked him a question about a person or place or event, he would share its history in exhaustive detail. A casual question about a building or a road would produce a thesis-like response; no detail would escape his attention or yours. His dear friend Judge Rudolph Sacco told me that he became reluctant to ask Judge Quirico about his wartime service in the India-Burma theatre, because in response, the judge would have to take him all around the world before they got to Burma. And once, after Judge Quirico had graciously escorted Judge Sacco's niece around Boston's Freedom Trail, Judge Sacco had to assure his exhausted niece that no one had ever had a tour of the Freedom Trail like she had. But like everything else in his life, his love of history and fascination with its details was above all else a reflection of his fascination with humans and how they conducted themselves.

These traits -- the attention to detail and the importance of the historical record -- would manifest themselves when he became a judge. To lawyers who appeared before him there was something particularly reassuring to know that their matter, no matter how important or trivial, would receive the careful consideration, the painstaking creation of the record and the thoughtful analysis that Justice Quirico brought to everything he touched. Whether you were pleased with his conclusion or not, every litigant knew that nothing was ever glossed over. And, of course, there was the patience and courtesy he always projected from the bench. Shortly after his death, a letter to the editor appeared in the Berkshire Eagle. The author reported on a hearing he had attended at which Justice Quirico presided and where the attorney arguing the matter concluded his presentation by stating, "Your Honor, I have thoroughly researched the matter and I have a Massachusetts case right on point if I can find it here in my notes." Justice Quirico said, "That's fine." A few minutes of scrambling of papers took place, at which point the lawyer said, "I know its somewhere here," to which Justice Quirico said, "Take your time." Minutes went by, and the attorney became more and more distraught as he searched for the missing citation. Finally, the Justice said, "Perhaps I can help you. Are you looking for the case of Smith v. Jones?" "Oh, yes, your Honor, this is it!" the attorney replied, immensely relieved. "I think," Justice Quirico added, "you'll find the citation you are looking for at 350 Mass. 157 -- about halfway down the page." As the observer noted, there was no showmanship, it was simply Judge Quirico's gentle way of helping an attorney in distress. He had great respect for the legal profession and he believed it was a privilege for any of us to be part of it.

Mention has been made of the Small Loans trials. Justice Quirico's ability to move 144 indictments against a score of defendants from arraignment through two lengthy trials, during which the defendants took no less than 5,400 exceptions to his rulings, was accomplished with skill, patience, and an occasional light touch that kept the whole process from blowing up. It was an epic case involving at least twenty-five of the most prominent defense counsel in the city, many of whom later became judges. And certainly there was no mystery about the defendants' strategy: they intended to raise so many objections to the proceedings that somewhere along the line the trial judge would commit some error. Justice Quirico's strategy and what he saw as his responsibility was to give the defendants all the opportunity they needed to make whatever record they wanted to make so that this court could adequately assess his findings on its review.

It became sort of a war of wills as the defendants' seemingly endless objections to the proceedings met the careful and thoughtful denials by the judge each supported by extensive factual findings. Finally, the defendants launched their last motion to dismiss the indictments, this on the ground that the American flag displayed in the courtroom did not bear fifty stars on its blue field but only forty-eight, thus infecting the entire proceeding with error. As he did with all the defendants' motions, Justice Quirico listened quite carefully to defendants' argument and, without pause, reached for the Massachusetts General Laws, invited counsel's attention to G. L. c. 220, § 1, which provided that the national flag displayed in the court room need only be of a suitable dimension, which this one undoubtedly was, and calmly denied the motion. Jury empanelment began the next day.

I mean no disrespect for this court and certainly not to today's wonderful ceremony when I observe, at least for the historic record, that, although Justice Quirico was greatly honored by the privilege to sit as a member of the Supreme Judicial Court, I believe his heart was always in the Superior Court. He loved the unfolding human drama that takes place in the trial court, the ingenuity of trial counsel, the roles of the jury and the trial judge, and the uncertainty of the outcome. To him, I believe, it was a forum that put him closer to his fellow human beings. In any forum, however, Justice Quirico was a man admired by all of us who are privileged to be members of this bar. When he was first selected to be a judge by Governor Herter, Justice Quirico said to the press with his characteristic modesty, "I hope I can live up to what is expected of me." He did, indeed, in a multitude of ways embedded in the grateful memory of his colleagues at the bar who join me in supporting the Attorney General's motion.

Superior Court Judge Margot Botsford addressed the court as follows:

May it please the court: I am Margot Botsford, and I clerked for Justice Quirico in the 1973 to 1974 term. I speak today on behalf of Judge Quirico's law clerks, many of whom are here today, and also in the memory of four of Judge Quirico's law clerks who themselves died before Judge Quirico. I wish to focus on a little of what Judge Quirico meant to me and I believe to all my colleagues as his law clerks. Let me start with a story. As you have heard, Judge Quirico worked long hours in his lobby in this court house, very long hours. Not being one who felt comfortable leaving before my boss, I would often stay working in the outer office to the lobby that served as the law clerk's office. On a number of these evenings, the judge and I ended up going out to dinner, often in the North End. Going to the North End with Judge Quirico was an experience, especially in the warmer weather. Everyone on Hanover Street, it seemed, knew him, and for a law clerk, it felt like marching with royalty. But eventually we got to the restaurant. We sat at the table, and on one or perhaps two occasions, after we had ordered our food, the waiter brought a bottle of wine to the table. Now Judge Quirico did not really drink, and clearly had not ordered the wine, but when the bottle arrived, he looked around the room and briefly smiled. After the waiter had opened the bottle and left, the judge informed me that the wine was a gift from a man sitting across the room, who was someone he had sentenced to prison in a criminal case tried before him in the Superior Court years ago. This experience defined essential qualities of the judge -- a man of a remarkable memory, but more to the point, a man of such fairness and integrity that even those he had sent off to prison respected him.

For me, and I think for most, if not all my fellow clerks, clerking for Judge Quirico was a life-defining experience. I knew after about six weeks on the job, just watching and being with the judge, that what I wanted to do in life was to become a judge myself, and I spent the next sixteen years after my clerkship ended trying to figure out work experiences that would give me a chance to apply. One of his clerks, Gilda Tuoni, who teaches and practices in the field of legal ethics, believes she came to that field because of the introduction that Judge Quirico gave to her in ethics during his work as a single justice handling bar discipline matters, and his many conversations with her. For others, the clerkship has had more indirect effects on career paths, but I think we all feel that our professional and personal lives as lawyers and our approach to work has been immeasurably enriched by the year we each spent with him.

The judge had a love of law, but more than that, he had a love and fascination with the development of law in Massachusetts that was contagious. He is famous for his opinions that trace some aspect of common law back to the beginning -- his opinion tracing the origins of wrongful death as a cause of action in the Commonwealth, his decision about public rights on the Boston waterfront, his decision about degrees of murder -- but I think it's safe to say that on just about every case I and my fellow clerks worked on with the judge, the history of the law on the subject up to the point of the decision became an important building block for the ultimate opinion. When he was working on an opinion -- typing it by hand on his antique, black typewriter -- his desk and the floor around it would be piled with volumes of the Massachusetts Reports, many of them from very early days. He loved to immerse himself in the Commonwealth's legal history -- one of his clerks, Deirdre Robbins, formed an immediate bond with the judge as they poured over ancient source materials on Massachusetts law together during her interview for a clerkship -- and he also loved to talk about it. One of all of our favorite times of day as law clerks was the late afternoon, when the judge would tell wonderful stories about Massachusetts law and lawyers. His prodigious memory for detail shone. He would speak of the Small Loans cases, about which you have heard much this morning, focusing on vignettes of lawyers in that case and key moments in the trials. (An aside about the Small Loans cases: when one clerked for the judge, one had to find alternative closet space, because both the closet in his lobby and the closet in the outer room were filled to brimming with the Small Loans case trial transcripts, selected volumes of which would come out from time to time to point out a brief excerpt that would illustrate a story being told.) But beyond these cases, the judge would reminisce about his life as a lawyer in Pittsfield, and later his life as a judge on the Superior Court. He would talk about his experiences in the army. They were wonderful stories, and they were themselves wonderful lessons about the law, the legal profession, and about him.

What Judge Quirico embodied for all his clerks were qualities of humility, profound respect for others, and extraordinary patience. One of the tasks as a law clerk was to attend the single justice sessions of this court when the judge was sitting in that capacity. He could listen to the lawyers appearing before him for what seemed like hours. I would be squirming in my seat, wondering how he could still be listening to the same worn out legal argument being repeated and repeated, but he could, and he did. His core philosophy was to allow people to be heard, and to treat them with dignity and respect while they spoke. It was a lesson that I think we all needed to learn.

The judge was a man of a conservative outlook, and a man who prized tradition. It is fair to say that he and his law clerks did not always share the same views on the social issues of the day, but he was never disapproving. There were only two things I heard him grumble about. One wasn't actually a grumble, but an expression of incredulity: why would anyone who came from Massachusetts, and particularly from Berkshire County, ever want to move to another State to practice law? He didn't understand it. Among his law clerks are two who now practice in Maine, but I believe the judge found this departure completely acceptable, since in the past, Maine and Massachusetts were joined. The other complaint of the judge had to do with names. I served as a clerk in the fairly early 1970's. He was supportive of women practicing law, and of women being judges, and had no problems with many issues of so-called women's liberation. But surnames were a problem for him. He considered it a travesty, or at least a tragedy, that when people married, the woman kept her own name. Not because he saw the woman as subservient to the man, but because if this couple had two different last names, who knew what the children would be named, and tracing family lines and family history could be significantly impeded. (I must add, though, that although I strayed from the reservation on this point, the judge did not appear to hold it against me.) In his quiet way, Judge Quirico made all of us feel as though we were part of an extended family for him. Long after each of our clerkships ended, we saw him when he was in Boston, went to see him in Pittsfield, and some of us visited with him at his wonderful cottage by the lake in Hinsdale. We took spouses and children to meet him, sometimes with unexpected results -- a one year old son crawling to the Massachusetts Reports and happily tearing out yellowed pages of an ancient volume, an act of criminal vandalism that did not phase the judge. As a group, we celebrated his birthdays with him. As has been said about one of his colleagues, Judge Cutter, in a memorial some years ago, Judge Quirico was a gentleman and a gentle man. But what a strong mentor and source of guidance he was for all of us. As law clerks, we feel enormously privileged to have had the chance to serve with him.

Justice Francis X. Spina, speaking for the court, responded as follows:

Madame Chief Justice, Justices, members of the family of Justice Quirico, and friends: in accord with our tradition, we have gathered one year after the passing of one of our own to leave for others a record of our impressions of Francis J. Quirico, unadorned by eulogy. Former Chief Justice Edward F. Hennessey wrote of Justice Quirico that he "rose to his full height [on the Supreme Judicial Court] as a magnificent custodian of the common law of Massachusetts."1 He was well suited for the role, possessed of keen intellect, a phenomenal memory, a passion for history, and an abundance of common sense. Chief Justice Hennessey also referred to him having an "infinite capacity for taking pains," a trait undoubtedly enhanced by his skill as a master cabinetmaker.2 The opinions of Justice Quirico are noteworthy for their scholarly treatment of legal principles in historical context, and for their persuasive logic. Like the furniture he created, they have clean, elegant lines supported from within by mitered reasoning, and a satisfying, aged patina from the application of common sense. The final impression given by each piece is a result that is one of inevitability.

Justice Ruth Abrams has said that Justice Quirico was patient beyond belief. Who better than a patient judge would appreciate, as Chief Justice Hennessey wrote in his book, Judges Making Law, "that the common law evolves by accretion."3 The boundless capacity for patience that made him a magnificent appellate judge also served him well as a trial judge, and made him uniquely suited to preside over the Boston Common Garage trials and then the Small Loans trials. Those trials called for a judge who was capable of managing complex and protracted litigation smartly, fairly, with patience and stamina, and sensitive to the need for public scrutiny. Again and again Judge Quirico rose to the occasion.

The two Boston Common Garage trials, involving allegations of corruption in public building contracts, consumed eight weeks of trial time. On appeal there were one hundred eleven assignments of error in two appeals. The convictions were affirmed after the Supreme Judicial Court concluded that Judge Quirico had made no error.4 An error-free trial of that magnitude was, and still is, unheard of. It was a remarkable feat.

The following year, 1964, saw him assigned to the Small Loans trials. Those trials were preceded by sixty-five days of evidentiary hearings on pretrial motions. The first of the two trials spanned five months; the second, the longest trial in Massachusetts history, consumed two hundred twenty-two days over twelve months. More that twenty-five of the best criminal defense lawyers in the Commonwealth representing twelve defendants generated wave after wave of motions and objections. For a trial judge, it was the perfect storm. Judge Quirico's formidable grasp of the facts, the law, his prior rulings, and his anticipation of the issues on the horizon was utterly colossal. He stayed the course with unflappable calm, all the while making a complete record of every ruling to protect the rights of the parties and to assist the appellate court.

The consolidated appeals designated seven hundred assignments of error.5 After nineteen months of pretrial motions and trials it would have been perfectly understandable had there been an error or two, or three, or even fifty, perhaps during a moment of fatigue or a brief lapse in concentration. That would have been forgivable. After all, judges are human, too. Judge Quirico permitted himself no weakness. Seven hundred times the Supreme Judicial Court heard the cry of error, and seven hundred times it found no error. Not once did the Court have to reach the second stage of review to determine if error caused harm.

No litigant and no attorney ever heard him raise his voice or conduct himself otherwise than as a gentleman. He showed neither favoritism nor prejudice. No litigant and no lawyer ever could fairly complain that he did not receive a fair trial before Judge Quirico. The late Justice Paul C. Reardon, who served as Chief Justice of the Superior Court for over six years while Justice Quirico was a member of that Court, said that "what endeared him to everybody was not only his learning and his dedicated attention to his judicial task, but his modest spirit. He has been and is an exemplar of what a judicial gentleman can and should be. He has been patient and understanding in dealing with the lawyers before him. While others have jockeyed for preferment, he has moved ahead on his own merit, the best argument for his advancement being his own excellence."6 Justice Reardon also served with Justice Quirico on the Supreme Judicial Court for seven years, and said that "[i]t was a distinct pleasure to have him once more as a colleague and to be able to benefit from his wisdom and experience. Both in the consultations and on the committees on which we jointly served . . . I found him to be a force for good." 7

A colleague no less than Justice Benjamin Kaplan called him friend. Seldom one to intrude, but whose door was always open, Justice Quirico never stopped giving of himself. He was the personification of the motto "service above self," and in that regard he observed no distinction between duty and friendship. As a judge of the Superior Court he gave up his Saturday mornings to make himself available to the lawyers of Berkshire County to hear motions when the court was not in session, which was eight months each year. He initiated night sessions to accommodate Berkshire litigants and lawyers. It was characteristic of him to stop whatever he was doing to assist a colleague on the bench with a question.

A kind, gentle, and caring man, he was respected and loved by his law clerks. The people of his home town of Pittsfield shared those feelings. He often could be seen stopping to talk with many ordinary people he knew well, inquiring without hesitation about the well-being of particular family members. There are many anecdotes, but I would like to add one that is little known. There was an old eccentric country lawyer from Dalton, a small town near Pittsfield, who was a member of the Berkshire County Bar Association. He was dying and was spending his last days alone in a local hospital. This was back in the early 1970's, if memory serves me correctly. Justice Quirico, aware that the lawyer had no surviving family, visited him regularly in the hospital, sitting at his bedside. He did this in the name of the Berkshire County Bar Association, so the lawyer would be comforted in the thought that he had a family who were thinking of him.

On June 3, 1980, the Boston Bar Association conferred upon Justice Quirico its Award for Distinguished Judicial Service. The citation read, in part, "Massachusetts' judicial history will mark him as one of the great judges of [the twentieth] century." That, no doubt, will prove true. When Judge Quirico began his judicial career on the Superior Court in 1956, he was a virtual unknown in legal circles outside Berkshire County. When Justice Quirico retired from the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court on February 18, 1981, he returned to the Berkshires as quietly and uneventfully as when he first reported for judicial service twenty-five years before, without fanfare. His work was done. There was one difference, however. The shadow of a giant now reaches across the State and into every court room of the Commonwealth.

Madame Chief Justice, I join in support of the Attorney General's motion.

Footnotes

The court allows the motion that the Memorial be spread upon the records of the court.

- Edward F. Hennessey, A Tribute to Justice Francis J. Quirico, 3 W. New Eng. L. Rev. 164 (Fall 1980).

- Id.

- Edward F. Hennessey, Judges Making Law 9 (1994).

- Commonwealth v. Monahan, 349 Mass. 139 (1965); Commonwealth v. Kiernan, 348 Mass. 29 (1964).

- Commonwealth v. Beneficial Fin. Co., 360 Mass. 188 (1971).

- Paul C. Reardon, Justice Francis J. Quirico, 3 W. New Eng. L. Rev. 160 (Fall 1980).

- Id. at 161.