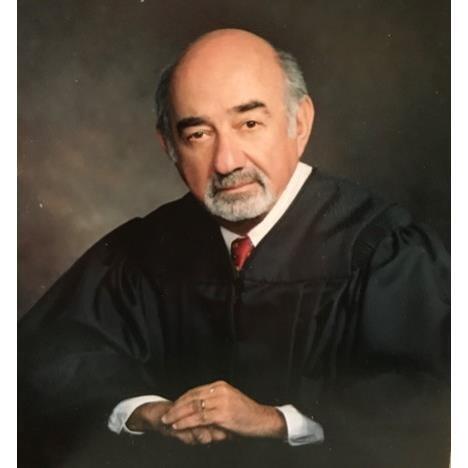

George Jacobs

Associate Justice memorial

102 Mass. App. Ct. 1127 (2023)

A special sitting of the Appeals Court was held at Boston on May 31, 2023, at which a Memorial to the late Justice George Jacobs was presented.

Present: Chief Justice Green; Justice Sacks; Supreme Judicial Court Justice Elspeth B. Cypher; retired Appeals Court Chief Justice Christopher J. Armstrong; and retired Appeals Court Justice James F. McHugh, III.

Chief Justice Green addressed the court as follows:

Good morning, and welcome to this special memorial sitting in honor of our former colleague, Justice George Jacobs. I want just very briefly to offer my own personal reflection on Justice Jacobs. When I joined this court in 2001, as part of that expansion, Justice Jacobs was among those most welcoming to me. He made special efforts to take me under his wing and mentor me, not just on the decisional work of the court but on its operations. He became a dear friend, and his presence looms so large in my memory that it is surprising for me to realize that we served together for less than two years before his constitutionally mandated retirement. It is a distinct honor for me personally to preside over this memorial sitting.

Andrea Joy Campbell, Attorney General, addressed the court as follows:

May it please the court: on behalf of the Attorney General's office and the bar of the Commonwealth, it is my honor and privilege to present a memorial and tribute to the late George Jacobs, who served as an Associate Justice of this court.

George Jacobs was born in Milan, Italy, in 1933, the only child of Jacob and Frances Jacobs who originated from Galicia, Poland (currently Ukraine). They fled religious persecution in Europe and settled in New Bedford in 1938 when George was five years old. He made lifelong friends while attending New Bedford public schools and was president of New Bedford High School class of 1951.

After attending Harvard College and the Harvard Law School, he returned to New Bedford and worked as a private practice lawyer from 1958 to 1975. He served as city solicitor for New Bedford from 1964 to 1970, under Mayor Edward J. Harrington, and then as assistant attorney general for the Commonwealth of Massachusetts from 1970 to 1974, under Robert H. Quinn.

He met Lois Bette Meyer at the New Bedford Jewish Community Center, where he had various jobs while he was a student. He told Lois that if she got into college in Boston, he would take her out to dinner. They began dating when Lois enrolled at Brandeis University as a first-year student, and he was a student at Harvard Law School. They were married on August 31, 1958. They celebrated sixty-one years of marriage and are the proud parents of Deborah Jacobs and her husband Justice Peter Sacks, daughter Sandra Jacobs and her husband Marc Friedman, and son Ronald Jacobs and his wife Judith (Marson) Jacobs, and six grandchildren, Justin, Lucas, Molly, Jake, Anna, and Jonathan.

George Jacobs had a general law practice in New Bedford, sharing an office with high school and college classmates Alan Novick and Harvey Mickelson. In the late 1960s, Justice Jacobs joined Maurice F. Downey in the first law partnership between a Catholic lawyer and a Jewish lawyer in New Bedford. He was appointed to the Probate Court by Governor Michael S. Dukakis in 1975, and then to the Superior Court by Governor Edward J. King in 1978. Justice Jacobs served on the Superior Court for eleven years until he was elevated by Governor Dukakis to the Appeals Court, in 1989, as an associate justice, where he filled seat number five, formerly occupied by the late Justice Donald R. Grant, one of the court's original appointees. He acclimated quickly to appellate work; during his fourteen years on the Appeals Court, he earned a reputation as a prolific writer of decisions and as a superb colleague and friend to every employee. He produced a total of 170 written decisions, of which 167 were signed opinions, two concurrences and one dissent.

After mandatory retirement from the court at age seventy, he became a full-time professor at what is now the University of Massachusetts Dartmouth Law School from 2003 to 2018 and a mediator at The Mediation Group in Brookline. George was active in New Bedford's Jewish organizations and served as a trustee of Southcoast Hospitals Group and St. Luke's Hospital. George was known in diverse circles for his integrity and humility, egalitarian spirit, imperturbable temperament, and sense of humor. Many considered him to be a role model for other judges for his intellect, fairness, and humanity. He was the first recipient of the St. Thomas More ecumenical medal awarded by the Fall River Diocese at its Red Mass in 1997. He is the co-author with Justice Kenneth Laurence of volume 51 -- Professional Malpractice -- of the Massachusetts Practice Series, published by Thomson Reuters West. He was quietly proud of what he accomplished as an immigrant kid from New Bedford and very proud to be an American. As he liked to say, "What a country!"

On July 7, 2020, at the age of eighty-six, he passed away peacefully at home, with family nearby.

It is an honor for me to be here today to pay tribute to Justice Jacobs, a truly outstanding judge and human being whose commitment to public service is an example to the entire legal profession. On behalf of the bar of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, I respectfully move that this Memorial be spread upon the records of the Appeals Court.

Justice Cypher addressed the court with her own remarks and then read aloud the remarks of Richard A. Pline, Esquire, as follows:

George Jacobs was a legend in Bristol County. As a longtime resident of New Bedford, he touched the lives of thousands through his work for the city, as a judge in the Probate and Family Court, and as a Superior Court judge.

I first encountered Judge Jacobs in the Superior Court, where I was trying to fend off a motion for new trial in two first-degree murder cases. It was a futile effort, as I gradually learned while Judge Jacobs questioned me. When I brought his memorandum of decision to the district attorney, which said that we had to have a new trial, and I asked whether we should appeal, the district attorney said, "No, if Judge Jacobs says that we need a new trial, then that's what we need, and that's what we'll do."

Soon after, he was appointed to the Appeals Court, and he set up his office in New Bedford with his law clerk, Richard Pline. I was always nervous when I argued in front of Judge Jacobs at the Appeals Court, because I cared very much what he thought, and if I was really terrible, or if I slipped or could not answer a question, then a discreet conversation might be had with the district attorney on the golf course.

When I joined the Appeals Court, George became a peer, but I found it so hard not to call him "Judge Jacobs." He also was my mentor, and he helped me learn how to write opinions. And, for a while, he was my driver. He would pick me up at my house at 5 a.m. in New Bedford on the mornings when we had court together. And as we went to Boston, he would give me all the secret shortcuts to the city. That was part of his mentoring.

He also patiently explained to me on the one -- and only one -- occasion that he let me drive was that I needed to go faster and that I needed to keep changing lanes or I would contribute to traffic. He had his way of driving, and I had mine, and he never let me drive again. And I do say "let" me drive, because he did express to me his opinion of woman drivers, not just me. He also always made sure that we were out of this court house by 3 P.M., preferably before 2:45, or we would be stuck on the Southeast Expressway for hours. And he also showed me the quickest way out of the city.

What I learned from George from spending time in the car that I would like to pass on, first, his family was the most important part of his life. He loved his wife, Lois, so dearly, and he often would express concern -- I would not say worry -- but concern about her happiness and comfort. That was a priority for him. He also loved his children deeply, and was very, very proud of them. And he was proud of their spouses and their children. And I know, Judge Sacks, he would have been especially proud of you being here on the Appeals Court.

One day, he told me a story about his son when he was a teenager. His son was out late at night with some friends, and George was worried. But he did not want to ruin a good time, and he did not want his son to believe that he was not trusted. So he had a local police officer drive him around the city until they located the house, peeked in the window, and saw that all was well. The police officer then returned George home, and he was able to go to sleep.

Second, George was a sincerely compassionate person. When I heard him express regret, it was usually because he had remembered something that he had said and he thought he was not understanding enough of the other person or maybe they had had a bad day, or he was too sharp with that attorney at oral argument, or maybe he should have been better with a difficult judge.

The final point that I would like to mention is that I learned from George how much he respected and cared for his longtime clerk, Richard Pline, and how much he came to cherish Cheryl Miranda and Maria Cardinale as his assistants. As retirement came closer, he had me work with Richard on a couple of cases, so that we could see whether we could work together. He wanted me to continue Richard's employment at the court, and so I did. That was, in fact, a very good deal for me, but I always felt that I was letting Richard down, because I was not George Jacobs.

George Jacobs, the man and the judge, was loved and respected. He left a major imprint on the Bristol County community and the Statewide legal community. Those of us who were able to spend time with him were given a great gift. He was always thoughtful and considerate of anyone who he was working with, be they someone who worked for him, someone he did not know, someone he might even be mad at; he was always thoughtful and considerate and kind.

George Jacobs had a brilliant legal mind and a shining, expansive heart. He is terribly missed.

The following are the remarks by Richard Pline.

I am grateful for the opportunity to add some remarks to this memorial celebration about my long relationship with George Jacobs as his law clerk and as his friend. I deeply regret that I am unable to attend in person, and I send my heartfelt regards to Lois and all of the family.

I had known George in his role as city solicitor when I worked as director of community development for the city of New Bedford. After leaving the city, I went to law school. Having passed the bar exam at the age of fifty-eight, I was doing some part-time legal work for an attorney in town. I was walking downtown on my way back from lunch one day when George wheeled up beside me in his car, rolled down the window, and said that if he was appointed to the Appeals Court, he would like to select me as his law clerk. This began the best thirteen years of my work as his clerk and a deepening of a profound friendship with one of the finest men I have ever known.

At his swearing in to the Appeals Court, George spoke of his debt to family, friends, and the area he grew up in after coming to New Bedford from Italy in 1938. Because of that commitment to the area, George immediately established that he intended for us to work from New Bedford, and he arranged to set up a modest office in the Superior Court building. George knew that the resources necessary to do his job were available locally and that it would be much more efficient to concentrate on the work rather than spend hours commuting out of town. His office raised the visibility of the Appeals Court in New Bedford and additionally provided a boost for the local legal community. He also promoted the growing trend of the Appeals Court holding hearings throughout the State outside of Boston.

George placed a high priority on developing and maintaining excellent relationships with the other justices, some of whom he considered to be giants in the formation of the court. On many occasions, he included me in conversations when he met with some of these justices, and he never made me feel out of place.

Always a champion of New Bedford, George took an active role in getting a law school established there. He asked to have his swearing in as an Appeals Court judge to be in his hometown at the then Southeastern Massachusetts University and later began teaching at what would become the UMass Dartmouth Law School. I believed George was often considered the head of the local legal community. He was asked to be the keynote speaker for the one hundredth anniversary of the New Bedford Bar Association.

It has been very difficult for me to summarize a relationship that is still deeply felt and greatly missed. I want to thank the court for holding this memorial today.

Justice Sacks addressed the court as follows:

I feel fortunate to be able to say that George Jacobs was my father-in-law, and that, after I met George and Lois's daughter Debbie in 1995, and after we married in 1997, I was welcomed into the family. George shared a lot of wisdom with me over the years. Today I will share a few things he said that had to do particularly with the law.

George was actually the first member of the Jacobs family I met, or perhaps encountered is a better word given the setting, which was when I appeared as a lawyer before him in the Appeals Court in the early 1990s. And I recall that at oral argument he had a wonderful way of inviting the sort of dialogue between the judges and the lawyers that is everyone's ideal for what an oral argument should be.

On one occasion, I was making some point that he evidently did not think held much water, and he said to me -- and it only works if one's voice has the sort of gravitas that his did and mine never will -- he said, "Come, let us reason together." He proceeded to ask a series of short and simple questions, in a very calm and conversational tone, patient, yet very much in control. He made me feel like I could -- and indeed, that I had better -- give up on some of my more aggressive arguments, because I could feel confident that, with him at least, common sense would ultimately rule the day. He just cleared away the underbrush of the case, and by the time the argument was over, I think the right answer was obvious to everyone in the court room.

So obvious, in fact, that the resulting decision was deemed unnecessary to publish, which has made it impossible for me to find after all these years. I do not remember who won the case or what it was about. What I do remember is his gentle approach, summed up in those words, "Come, let us reason together." It seemed at the time as if he was quoting some poem or proverb, but I had no idea what it might be. I looked it up recently and learned that it is from the Old Testament, the Book of Isaiah, and that the Hebrew word for "let us reason together," ya-kách, means "to decide, adjudge, prove, and argue." So it was particularly apt for the occasion, which I am sure he knew, although I did not.

Once I became a family member, we would sometimes discuss decisions of other courts, perhaps located nearby, perhaps in Washington. On one occasion I was expressing to him my admiration for what seemed to me to be the absolutely flawless logic of a decision in a criminal case. And he shook his head regretfully and told me, quietly, that he thought the author of that decision had, in his words, "no understanding of human weakness." And that really got me thinking, "so, is that essential to being a judge? You mean it's not just an intellectual exercise?" At that time, I was working in the Attorney General's office, representing State agencies, so I did not have many chances to work an understanding of human weakness into the sometimes rather bureaucratic-seeming arguments I made on behalf of my clients. But George's thought stayed with me, and I think I am a better judge and a better person as a result.

In the late 1990s, after years of seeing the green advance sheets every week with the long lists of the unpublished Rule 1:28 decisions of this court, I asked him, does it ever get old? If the decisions are not being published, how interesting can they be? And he said he always felt a sense of great anticipation when the briefs for the next month's sitting were delivered to him -- in those days, they came in tall stacks of manila envelopes -- and, as he put it, he would happily contemplate the stack and imagine what fascinating problems might await him inside each envelope. And, of course, each case was very important to the parties, even if no one else. Every case was an opportunity to solve a problem, and every case had something interesting in it. And that has certainly proved to be true in my time here.

Finally, I recall what he said to me after my first day of hearing arguments as an Appeals Court judge, in 2016. I asked if he had any advice for me. And he said, "Don't let the perfect . . ." and I thought to myself, well, okay, I know where this is going. But no, that was not it at all. He said, "Don't let the perfect be the enemy of the fair." Which he never explained further, probably because he thought I would understand it better if I figured it out for myself. I think what he meant was, yes, every case presents some intellectual puzzle, but do not fool yourself into thinking that you are doing your job just by solving the puzzle. You can come up with a beautiful logical structure, but it does not necessarily produce a result that is just or fair or that anyone should feel good about. Take account of human weakness. And remember to reason together, to listen -- not just to your own brain or your own gut -- but listen to the lawyers, and to your colleagues on the bench, and to the others here at the court who he felt so privileged to work with. And work with them to find common ground that makes common sense.

We should all be so lucky as to have someone like Justice George Jacobs in our professional as well as our personal lives.

Harvey B. Mickelson, Esquire, addressed the court as follows:

I want to sincerely thank those who were kind enough to suggest that I should be part of this memorial service honoring my good friend, George Jacobs. When I first received the invitation, I considered what I could possibly say about George that has not already been said. His various careers as an attorney, judge, educator, board member of various charities, and genuine good guy have certainly been well documented.

To be in this court room under these circumstances in the presence of justices of the court is probably the last place I would have expected myself to be saying a few words about George Jacobs. Our relationship was far removed from these circumstances.

So, who was this guy, George Jacobs? Strangely enough, I only think of him as being George Jacobs, my old friend. George, a down-to-earth, considerate, affable guy, who never attempted to impress you with his accomplishments or station in life. What he appeared to be, he was.

George and I started our relationship over eighty years ago in the school yard at the Betsey B. Winslow School in New Bedford when we both were around seven or eight years old. As we progressed through elementary school, we became close friends and together became the recognized champions of the grammar school step-ball league. Our achievements were well recognized. In case you did not know, the equipment for this game was an old tennis ball and sometimes a broken broom handle.

Those years included all of World War II, and we, as other classmates did, spent a good deal of time collecting newspapers and picking milkweed pods, which we delivered to school to be used in the war effort. Air-raid drills were also part of our grammar school experience. To me, they were just a game, but I wondered what impact they may have had on George, who had the experience of leaving his homeland while bombings were actually taking place.

As the years passed, we were good friends and playmates. As best as I can remember the tenor of that relationship lasted until we went on to New Bedford High School. At that point in our lives, I befriended a girl named Bernice, who later became my wife, and who died many years ago. Through her and the growth of our gang of friends, I began to learn more of George's background. When his mother and father and he escaped the scourge of the Nazi influence in the late 1930s and came to the United States, they were welcomed by an uncle who lived in Fall River, and they ultimately settled in New Bedford. When the family first came to New Bedford, they were befriended by Bernice's mother and father and spent a great deal of time at her family home. Her family consisted of eleven children. She was around George's age, so they became playmates. She often told me of how smart George was, how many languages he could speak; they had a bond that lasted until her death. George lost a dear friend, but he remained mine for the next forty years. I maintained a close relationship with a few of Bernice's brothers and sisters. George would always ask me how they were doing. He maintained an affection for the family and referred often to those early years in their home.

Throughout the high school years, George achieved at all levels. After school in the afternoon, he worked at the Jewish Community Center, where our gang would go to socialize. Even at that stage of his life, his leadership qualities, administrative ability, engaging personality, and basic good nature were impressive to say the least. Those who had the opportunity to be in contact with him, whether adolescent or adult, could readily see that this guy was smart -- really smart.

George, of course, went off to Harvard, which was not a shocker to anybody, and I went off to a prep school, which was not a shocker to anybody . . . but somehow, I also ended up at Harvard. Don't even ask me how. Those years went by rather quickly, and I would see George from time to time, but each time, somewhere in the conversation, there would be a reference to the old days, to high school football and step ball.

When I was admitted to the bar in 1959, George was practicing as an individual attorney and asked me whether I would like to share offices with him. We did practice together for approximately five years. During that time, George was being more and more recognized for his ability and was attracting more significant clients. Those were good, rewarding, and pleasant years.

One day, George said, "I gotta talk to you." He told me that he was approached by the then city solicitor of New Bedford to become his assistant and to join him in his law practice as a partner. George was not heavily involved in politics, but he had achieved such recognition as a practicing attorney that the addition of him to the city solicitor's office gave to it an expertise that it lacked, and his partnership in the new firm created a more powerful and respected entity. It was a huge opportunity for him. George asked me how I felt about it and whether it would interfere in our relationship and hurt my practice. I told him that for his and his family's benefit, he would have to make the change. Fairness and concern for others were always part of George's demeanor.

Onward to marriage, kids, law practices, judgeships, our relationship and basic understanding of each other and the importance of that relationship never changed. I had boats for many years, and George and Lois would stay onboard with us for a week or so every summer. George said to me one day, "I never had a bad day on the boat." And I can readily say, I never had a bad day with George Jacobs.

George never really changed. We had a mutual friend from the old gang who used to call George "Giuseppe" and continued to call him Giuseppe for years after he became a judge, and those two had the best time together just laughing. George was still Giuseppe or little George in my eyes.

As the decades passed and our children came and went and our paths and occupations developed, there were years that I did not see much of George, but we would finally bump into each other and I instantly knew that all that was important to our relationship in the formative years was still very much intact and our meetings were filled with the same concerns for each other, our families, the kids, business, and, more importantly, how are you really doing. I knew and readily told anyone that would listen that George was the only real friend I had.

I could go on for hours relating incidents that occurred in our lives during these eighty years, but each comment or story would project that George, to me, was always the kid from the playground, the close friend of our family, and the quiet, unassuming, caring, and sensitive human being who documented his life with goodness and caring.

George would often talk about how fortunate he was to have had the opportunity to be in this country and New Bedford. In his quiet, understated way, George was an achiever. He always had goals, and the opportunity to become a judge allowed him to realize his greatest goal. I believe he considered it to be an honor to his parents and family and allowed him to apply the authority that he received in that position in a positive and fair way.

I do not know whether George even thought of this, but in many ways, he was called upon within the community to join organizations that made it clear that Jews were not welcome. Entities such as the country club, the hospital, had little or no representation on their boards or membership by Jews and probably nonwhites at that time. When the walls began to come down, they sought him out and invited him to lead the way. George and one other well-respected attorney in New Bedford were the first to be invited and set the precedent for the many others who followed. Imagine little George, a Jewish immigrant, being driven out of his homeland to become instrumental in the removal of religious barriers within our community.

So, except to recognize his accomplishments, our relationship over all those years never changed, always my very dear friend.

Even in the waning years of his health, he always reached out to me and made certain that I was aware of his medical problems, the impact that it made on him, and even one night to inform me that he was going in an ambulance the next day from Dartmouth to a Boston hospital and he did not want me to worry if I could not reach him. We managed to talk to each other often after he moved to Needham with the same concerns for each other involved in every conversation. I told his son Ron that I was going to miss him, and indeed I do.

In closing, again, I want to thank those who were thoughtful enough to allow me to participate in this occasion, which, I believe, appropriately completes the career of George as a judge. Each endeavor that George participated in concluded with him leaving an outstanding reputation and fond memories of him for those who participated with him.

Ronald M. Jacobs, Esquire, addressed the court as follows:

First, my family and I want to thank the court and all those behind the scenes responsible for today and this opportunity to remember my father. As a member of the Massachusetts bar, I speak for my family members in attendance today.

My mother, Lois; my sister, Debbie Jacobs, and her husband, Justice Peter Sacks; my sister, Sandy Jacobs, and her husband, Mark Friedman; my wife, Judy, and our sons, Justin and Lucas; my aunt and uncle, Ina and John Portnoy, and their daughter, Rachel Daly, also a member of the bar; as well as four grandchildren who could not be here today, Molly, Jacob, Anna, and Jonathan -- we all thank you.

My father's accomplishments were many and varied and remarkable, even without taking into account his very humble beginnings in this country. But his remarkable accomplishments are not what sum him up for us. Rather, it was his devotion to family and his overwhelming instinct to protect us; his egalitarian spirit and distaste for pretense; his independence and self-reliance; his equanimity and imperturbable temperament; his humility and, of course, his sense of humor; and, perhaps most notably, the fact that none of his success, as far as we know, ever came at the expense of another person.

It is difficult imagining a purpose in life for which my father was better suited than being a judge -- whether in the different contexts of the Probate Court where he was first appointed at the young age of forty-two, the Superior Court next, and then this court, where he sat until mandatory retirement. The capacity, incisiveness, and versatility of his intellect, combined with his temperament, and perhaps above all his fundamental sense of fairness and reasonableness, made him perfectly suited for the role of judge.

I also think it is fair to say that my father did not set out on the path that ultimately found him. Actually, I think in his heart of hearts, he envisioned himself playing second base for the Red Sox. One of the many things that I can thank him for was having learned at a very young age the foolishness of such a goal -- I instead set out to be point guard for the Celtics. And he supported my pursuit by reminding me, appropriately, to keep studying.

What we, his family, heard the most from him about time on the different courts, and saw in practice, was how much he enjoyed the camaraderie and company of those with whom he worked -- certainly, the other judges, whose legal skill and intellect he admired, but definitely not only them. He relished and valued his relationships with the clerks and other administrative staff, court reporters, court officers, and the various court house personnel.

It sounds trite, but treating all people the same, regardless of background or station in life, was something we saw without exception and also without fanfare. Maybe this was the influence of his starting in this country as an outsider. I was particularly close to my father and was most fortunate to have spent a lot of time with him in many different contexts. His comportment in this regard was genuine and unwavering. To me, that is perhaps his greatest legacy.

He would be telling me to wrap it up at this point and land the plane already. Before I do, I want to repeat one thing that someone said to me the day before my father's funeral, now almost three years ago -- and this was a highly accomplished and respected person by any measure. He said that he could only hope, on his very best day, even for just a moment, to be just a little like my father. I could not agree more.

My father was asked dozens of times to perform weddings, deliver eulogies, give other speeches, and the like. We found one of his eulogies, and I think it is most appropriate to include his own words, which he delivered in memory of another: "If measured by the memory of those who loved him, who respected him, who worked with him, who laughed with him, and who were inspired by him, his life truly was full and everlasting."

That my father, an immigrant, found a calling to which he was so well suited -- being a judge, a position of honor and prestige -- while adhering to the ideals by which he consistently led his life, and all without any sort of advantaged beginning, exemplifies many different elements of the American Dream. Indeed, as he would say -- and often did say -- "What a country!"

Retired Chief Justice Armstrong responded on behalf of the court as follows:

George Jacobs came to the Appeals Court shortly after the start of its seventeenth court year. The Appeals Court, mired in backlog, would be without the service of Justice Donald Grant, one of the court's six original members and one of the most productive, who had submitted his resignation to the Governor in the spring of 1988, so as to give the Judicial Nominating Commission time to have a replacement in place for the start of the sixteenth court year, 1988 to 1989, but the position had lain vacant that entire court year; so the court entered the 1989 to 1990 court year with only nine judges in active service.

Then shortly after the start of the 1989 to 1990 season, an unanticipated second vacancy arose. Supreme Judicial Court Chief Justice Edward Hennessey had reached the mandatory retirement age in April and had been made to retire from the judiciary. His replacement came in June 1989: Paul Liacos, who had been an Associate Justice for eleven years, replaced Hennessey as the new Chief Justice of the Supreme Judicial Court. That elevation left an Associate Justice vacancy in that court, and the Appeals Court Chief Justice John Greaney was elevated to the position on September 5. That appointment left vacant the position of Chief Justice of the Appeals Court. Four candidates were considered, all Associate Justices of the Appeals Court. The Governor selected Joseph Warner to be the Chief, leaving, of course, a second vacancy in the position of Associate Justice.

Then, in 1988, the Legislature had recognized the court's problem of unbelievable backlog and addressed it by authorizing four additional Associate Justice positions. Thus, by autumn of 1989, the Appeals Court should have had fourteen judges in active service, but the fact of the matter was that we had only eight. We had six vacancies and a hopeless backlog of cases waiting to be heard. That was the court to which George Jacobs was appointed in November 1989. I am surprised he took the job.

From the court's point of view -- I speak here for the eight of us who were active judges at the time -- we had every reason to be optimistic about the appointment. Our new associate obviously had an extensive, well-rounded background -- a background whose breadth exceeded any the court had ever had. A background that included time in private practice, corporation counsel, Attorney General's office, probate judge, Superior Court judge -- and came with a reputation for quiet excellence. Only Allan Hale had experience as corporation counsel; no one had ever served in both the Superior Court and the Probate Court. And that, by the way, is, I think, true to this day. That was a unique qualification George had. What more could we ask?

Our hopes were more than amply fulfilled. George turned out to be all we expected and more. He took a full judicial load, was infallibly punctual with his work, was an excellent scholar and lawyer -- a book lawyer. He had very sound judgment and a contagious sense of humor, and beyond the sheer load of casework, he plunged deeply into the chronic administrative problems of the Appeals Court -- the ever-present problem of how to get current in the work -- and made creative suggestions. No one spent more time thinking through the Appeals Court's chronic problem of second panel and how to handle disagreement between panels of the court.

So far as personal qualities go, George was perfectly matched to the role he played at a difficult time in the court's history. His infallibly good nature surmounted all personal difficulties on any panel he sat on. His brilliance -- I think he was unquestionably a brilliant lawyer -- his brilliance lay in the ability to show a panel, trying to adhere to the law, how it was possible to do so and still do justice in the case.

He is remembered with enormous fondness by all of the judges on the court. We were all extremely sorry to see him go. He was just a perfect colleague, a brilliant mind, and a wise person. He was a great man, a great friend. We all deeply missed him. I, myself, had to leave the court three years later. But I am so glad I was there for the thirteen years that George Jacobs was a member of the court. It was that, coupled with the enlargement of the court, that made it my favorite time for being a judge on the Appeals Court.

Attorney General Campbell, the judges of the court have conferred, and they allow your motion, and this Memorial shall be spread upon the records of the court.