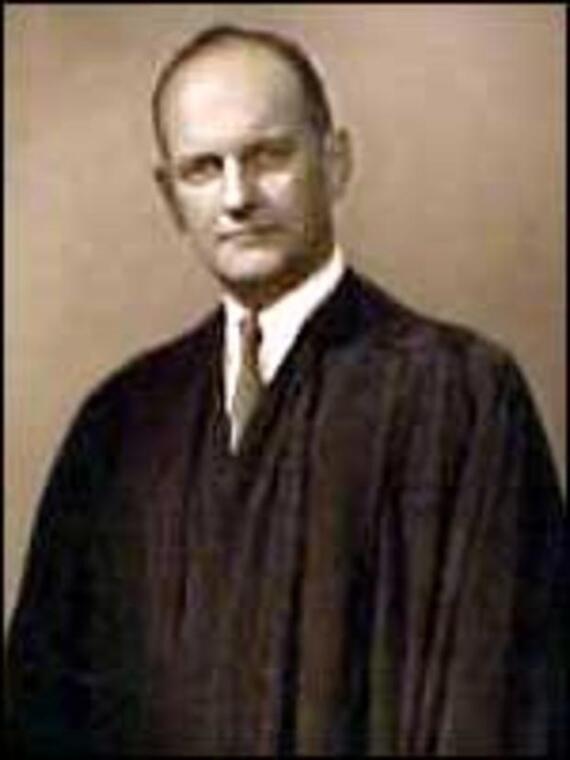

John Varnum Spalding

Associate Justice memorial

379 Mass. 931 (1979)

A special sitting of the Supreme Judicial Court was held at Boston on November 20, 1979, at which a Memorial to the late Justice John Varnum Spalding was presented.

Present: Chief Justice Hennessey, and Justices Quirico, Braucher, Kaplan, Wilkins, Liacos, and Abrams.

Francis X. Bellotti, Attorney General, addressed the court as follows:

May it please the court: As the Attorney General of the Commonwealth it is my privilege and honor to present a memorial in tribute to the late John Varnum Spalding. I present this memorial address not merely in my own name, but also on behalf of the bar of the Commonwealth and of the committee which has arranged for these proceedings and has participated in the preparation of the memorial which follows.

John Varnum Spalding was an Associate Justice of the Supreme Judicial Court from May 3, 1944, to July 1, 1971. This period of over twenty-seven years was one of the longest terms of service in the present century. He was a member of the court with four Chief Justices and wrote over one thousand opinions. Decisions in which he participated appear in forty-five volumes of the Massachusetts reports (volumes 316 to 360). His service on the court was marked by a distinction of judicial performance which places him with the foremost appellate judges in the history of this court. It is thus especially appropriate that an account of his career be stated for the records of this court.

Mr. Justice Spalding was born in Newton on December 8, 1897. He was the son of George Frederick Spalding and his wife, the former Florence Atherton Faxon, an accomplished musician. He attended the public schools of Newton and received his A.B. degree from Harvard College with the Class of 1920. His college career had been interrupted by World War I. From the Reserve Officers Training Corps at Harvard, he had gone to Plattsburg and then to the Infantry School at Camp Lee, Virginia. There he was commissioned a second lieutenant in the autumn of 1918. He returned to college after the Armistice of that year. He took his LL.B. degree at the Harvard Law School with the Class of 1923.

Mr. Justice Spalding was an able performer on the violin, an interest greatly encouraged by his musical mother. He only briefly considered becoming a professional musician, but concluded that he had started too late to achieve real distinction as a violinist. He occasionally remarked, "The second prizes in music are not very good." He, however, did pay for his law school education in large measure by forming a dance orchestra. His group was much in demand for social affairs in the Greater Boston area during his law school years. He retained a lifelong interest in serious music and was a constant attendant at concerts of the Boston Symphony Orchestra until his failing hearing prevented him from enjoying the music.

In 1923 he started practice in Boston in the office of Storey, Thorndike, Palmer, and Dodge, where he remained for two years. For a short time he was legal adviser to the local Prohibition Administrator and then had the opportunity to obtain trial experience as an Assistant United States Attorney. He held that position, beginning September 1, 1926, for three years. In this post he first served for a few months under the United States Attorney, Harold P. Williams, later his colleague on the Superior Court and on this court. As Federal prosecutor, he handled a wide range of Federal criminal matters which fortunately involved a considerable number of questions more interesting than many of the cases presented during the Prohibition period under the Volstead Act.

In 1929, Mr. Justice Spalding returned to private practice with the firm of Hale, Sanderson, Byrnes, and Morton, each of whose then members formerly had been with the office of the United States Attorney. He later formed a partnership with an older friend, A. Leslie Harwood. With both firms he engaged in an active general practice which included a substantial amount of litigation. He was appointed frequently as a master. He participated in the liquidation of banks in the Lawrence area during the depression years. For a period he served as chairman of the Newton Licensing Commission. He also, for twelve years, taught courses in the law of property and evidence at Northeastern University's law school. His law clerks here found that he continued his teaching habits in useful instruction to them.

On February 25, 1942, he was appointed by Governor Leverett Saltonstall to be an Associate Justice of the Superior Court. There for two years he encountered the usual variety of cases for a judge of that court and gained quickly a fine reputation as an effective and sound trial judge. Upon the retirement of Mr. Justice Charles Donahue in 1944, he was appointed by Governor Saltonstall to be an Associate Justice of this court.

On this court, he had occasion to write opinions on every aspect of the law. It was a period during which the law was developing rapidly and in which novel statutes required examination and interpretation. In the field of criminal law, in particular, there was substantial expansion of measures designed to afford greater protection of the interests of criminal defendants. Mr. Justice Spalding rapidly was recognized by the bar as a judge who paid proper deference to sound precedent, but who was prepared to participate in sensible innovation. It quickly became apparent that each of the Chief Justices, with whom he served could assign to him any case, no matter how complex, with confidence that the opinion would be thorough, persuasive, and in the public interest.

The Justice wrote clear and concise opinions. It was his intention to set forth as simply as possible the grounds of the decision and the reasoning by which the court reached its result. He greatly admired Chief Justice Stanley E. Qua and strove to frame his own legal writing in a manner comparable to the clarity of expression achieved by that great jurist.

For many years, Mr. Justice Spalding served on the Rules Committee of this court, and for fifteen years as its chairman. The Federal Rules of Civil Procedure had been adopted shortly prior to World War II and the changes wrought by those rules made desirable careful reexamination of State court procedure. Studies initiated by him and his committee led to various efforts to achieve for the State courts some of the advantages of the new Federal rules. Perhaps the most important of these innovations was the expansion of pretrial oral discovery by General Rule 15 in 1965. His committee also in 1958 framed a provision for suitable representation of indigent criminal defendants (General Rule 10) well before that was required by the decision in Gideon v. Wainwright, 372 U.S. 335 (1963). Other rules drafted under his direction related to contingent fees (General Rule 14, 1964) and (in 1958) the regulation of limited practice by law students for indigent criminal defendants (General Rule 11).

Upon his retirement in 1971, the Boston Globe editorially referred to the length of his service and the number of his opinions. It then went on to say that these statistics "do not begin to convey the learning, the sound judgment, the perceptive understanding, and above all the compassion and sense of justice that have distinguished Judge Spalding's decisions -- and also his dissents."

Mr. Justice Spalding had a very happy family life. In 1930, he married Jacqueline Veen, a charming lady of French and Dutch antecedents and a native of Bordeaux. She had wide literary and social interests and a lively capacity for stimulating friendships. They shared many common interests, including tennis, in which they both participated vigorously until after the Judge's retirement. In this they were great amateur competitors. It was a close question among their friendly adversaries which was the better player, although the Justice himself conceded that preeminence to his wife. Mrs. Spalding maintained close contacts with her French family and owned a share in a house in Arcachon near Bordeaux. Thus she encouraged her husband to spend their vacations in Europe whenever the heavy work of the court permitted. Their two children succeeded to the scholarly interests of their parents and each earned a degree of Doctor of Philosophy, one at Yale and the other at the University of Connecticut.

Mr. Justice Spalding was a constant reader, particularly of history and biography. He had examined carefully the available literature on the Civil War period, and the later nineteenth century history of this nation. Thus he was a natural selection for membership on the Harvard Overseers' Committee to Visit the History Department. He also for a time was a member of the committee to nominate candidates for election to the Board of Overseers, and was a fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. He was for several years a useful adviser to Professor Austin W. Scott, the reporter for the American Law Institute's Restatement of the Law of Trusts. His membership and activity in other organizations reflected the diversity of his interests, the Club of Odd Volumes, the Curtis Club, the Law Club, the Harvard Club of Boston, and the Harvard Musical Association. He served terms as president of the Badminton and Tennis Club and the Union Club.

He was awarded honorary degrees by Suffolk University (S.J.D. 1952) and by Northeastern University (LL.D. 1955). On the former occasion his citation stated that "his concise, lucid, and scholarly opinions have added dignity and respect to the" court. The Northeastern University citation referred to the "ability shown during . . . [his] career in public service," to his "adherence to the highest ideals of . . . [his] profession," and to the "personal qualities which" had brought him the affectionate regard of all who know him.

After his retirement, Mr. Justice Spalding was Chairman of the Massachusetts Judicial Council from 1971 to 1974 and frequently served this court as special master and commissioner to deal with the increasing volume of post-conviction cases initiated by prisoners in the State's correctional institutions. He wisely developed the procedure for this type of litigation on a case by case basis, thus avoiding the inflexibility sometimes found in efforts to codify this form of review.

From 1973 on, Mr. Justice Spalding, following a stroke, was not able to participate in general activities. He faced ill health with courage and cheerfulness. In this period, his interest in biography and history was to him a great resource and pleasure. He read constantly. He died in Newton on July 16, 1979.

The extent of Mr. Justice Spalding's contribution to the development of Massachusetts law and to the day-to-day administration of justice in the Commonwealth's highest court can be understood fully only by those close to the work. During all of his term of service, the volume of cases reaching the court was far greater than in most comparable State courts. The court's appellate jurisdiction, as a practical matter, was without any limit except the restraint of litigants. The Appeals Court was not created until a year after he had left the bench. There was, as at present, for each Associate Justice, in addition to the appellate work, an average of two months of service each year in the county court's "single justice" session.

Of this unremitting burden, Mr. Justice Spalding always carried more than his fair share. His appellate work was kept up to date. His single justice decisions were prompt and incisive. He was never responsible for the denial of justice by delay. With the bar he dealt always with fairness, consideration, and courtesy. Lawyers knew that their cases had received from him full, deliberate study. He deserved and received the respect of all who came in contact with him. For all his years of faithful, enlightened service, the Commonwealth will remain in his debt.

On behalf of the bar of the Commonwealth, I respectfully move that this Memorial be spread on the records of this Court.

Sumner H. Babcock, Esquire, addressed the Court as follows:

Speaking on behalf of the bar in support of the Attorney General's motion, these remarks will attempt to portray the man, John Varnum Spalding.

He was not a complicated person. On the contrary, he was direct and straightforward, and resisted complexity. Throughout his entire career as a lawyer and a judge, neither opposing nor losing counsel or anyone else ever intimated or thought that he acted other than as he deemed right, free from any improper influence or motive.

Although he was a bulwark of rectitude, he was not stuffy. He had abundant common sense -- more than most persons possess -- as well as a sense of what would be the practical result of a court decision.

He had a delightfully droll sense of humor -- earthy at times -- and enjoyed recounting anecdotes -- of which he had a vast store -- about famous personages -- legal and judicial, and about ordinary persons. At times the object of his humor was himself. As a result it could not be said that he took himself too seriously -- an unhappy characteristic if a judge has it.

He read prodigiously -- more books than anyone I know -- not fiction but non-fiction. While some seek to escape the world temporarily and vicariously by reading mysteries, detective stories, or novels, he read primarily histories, historical books and biographies. Although he was what is sometimes called a Civil War buff, his knowledge of American history was remarkable, based as it was on his study of history in Harvard College and his later extensive reading.

And what he read, he remembered. He had a remarkably retentive memory which served him in good stead in his profession and as a judge. His ability to recall the names of the parties in prior decisions of this court and cite them by book and page was perhaps equalled by none of his colleagues with the exception of Mr. Justice Ronan.

But it would not be accurate to describe him as a cloistered scholar -- he was an active man. In his younger days he rode horseback, but his first love was tennis, which he enjoyed playing several times a week practically all his life. Mostly he played doubles -- men's doubles, and mixed doubles with his attractive wife. He was left-handed and she was right-handed, and their abilities were about equal. They once won a minor -tournament in Rye, New Hampshire.

The Spaldings enjoyed dining with others and having dinners in their home. He took pleasure in club meetings and dinners. He regarded himself justifiably as being something of an authority on wines, and his views on the subject may have been influenced by his wife who came from a family of wine merchants in Bordeaux, France. He was a friendly, gregarious man, with a wide and varied circle of friends -- judges, lawyers, doctors, men of other professions, businessmen, former students, school and college friends, and others.

After law school he was a member of the Harvard Musical Association and regularly attended suppers and concerts there as well as concerts of the Boston Symphony Orchestra. His familiarity with, and fondness for music, aided by his retentive memory, is illustrated by the fact that he could hum the dominant themes in most of the movements of better known symphonies.

His outside interests never caused him to withdraw his interest in his family or diminish his participation in family affairs. He was most proud and appreciative of his wife, and the concerns of his children were his also. They were a closely knit group, and he was always a perceptive and devoted husband and father.

He possessed two other attributes which, in my opinion, were major reasons why he was an exemplary judge, both on the Superior Court and the Supreme judicial Court.

First, he was "of the people," he knew human nature; he understood, could relate to, and empathize with all kinds of people. He knew first hand their prevalent prejudices and mental attitudes. He learned these things naturally as part of his life -- as a child learns to talk. He grew up in that part of Newton known as Newton Center, which in those days was like a village, where he was known to most and most of the inhabitants knew him as well as most everything about each other. He graduated from Newton High School and in effect worked his way through Harvard Law School. He served as Assistant United States Attorney and had practiced privately in three different law offices so that he had dealt with people concerned in matters in many different areas or sectors of the law. He had been a member of the board of the City of Newton charged with the granting of liquor licenses, and he had sat as a master in a good many cases listening to parties, witnesses and expert witnesses.

As a result, learned though he was, he never lost the common touch. Listening to oral testimony or impassioned arguments of counsel -- or reading the record on appeal he could discern accurately underlying motives, probable truthfulness, or the opposite, and in general appraise what he heard or read to give it the proper weight. In discussing an argument before the full bench when Chief Justice Qua was sitting, comment was made about a ploy by counsel in argument, and Justice Spalding was heard to say that the Chief "saw right through counsel to his backbone." Justice Spalding had the same ability.

Second, he had a strong innate sense of justice -- fair play -- for all persons regardless of race, color, creed, or social or financial condition within the framework of the law. This quality manifested itself in different ways. On the trial court he treated parties, witnesses, and counsel courteously and with impartiality. In writing an opinion for this court he sought to state fairly the various contentions, and explain his decision so it would be clearly understood by attorneys on both sides. He used to say that while his opinions might not display the style of Mr. Justice Holmes, his aim was to make them clearly understandable to counsel on both sides and to the bar. Within the framework of the law he also wanted his opinions to be fair to and match the mores of society -- a cross section of which he knew so well.

It is fitting and appropriate that the motion be allowed and that we honor Mr. Justice Spalding in this manner.

John T. Noonan, Esquire, addressed the Court as follows:

May it please the Court:

As a member of the bar and a long-time friend of Judge Spalding, I would like to join the previous speaker in asking that the motion of the Attorney General now before this court be allowed.

The appraisal of Judge Spalding's life and accomplishments and a delineation of the kind of man he was have been so ably and fully presented in the statements of the Attorney General and Sumner Babcock that I will not try to add to what has been said. I would like, however, if I may, to speak of a few of my contacts with Judge Spalding which were in their way unique.

First, let me say that although I was in law school with Jack -- I find it hard to call him anything else -- only a year ahead of him -- I did not know him there or consciously set eyes on him. My first recollection of seeing him is in 1926 when he was an Assistant United States Attorney in this district. I liked him and we became friends and our families became friends, a friendship which lasted some fifty-three years. One of the things contributing to this friendship occurred early in our professional lives. I was counsel in a matter which, while not in litigation, required preparation for possible litigation. The matter was complicated and I needed help. For various reasons my own office could not furnish it. I asked Jack to associate himself with me and he agreed. We worked happily together for some months and into the summer. Jacqueline, his wife, was then returning to France, according to custom, to visit her family. Jack, also according to custom, planned later to join her for his vacation. It was clear that unfortunately we would not be finished with our work when it was time for him to leave. I urged him to go, but I left the decision entirely to him. He decided to stay and finish the job. In this case I already had an opportunity to see the penetrating quality of his mind and his ability to analyze and deal with a complex situation. I now had an opportunity to see the firm sense of obligation which he felt to carry through something he had undertaken.

Another early bond between us lay in the fact that we both taught in the evening law school of Northeastern University, Jack for twelve years, myself for five. We saw each other in this connection, attended faculty meetings together, and were happy to find that our ideas so frequently coincided. It has been said that the way to learn law is to teach it. I believe from my own experience that to be true, and during those twelve years of Jack's teaching experience, he was quietly preparing himself, I believe, for the great service he was later to render as a judge of this court.

A number of years after we both had finished our teaching at Northeastern, the school for various reasons, felt compelled to close. A number of years again after that, however, it reopened as a day school, and I was happy to be asked to serve with Judge Spalding on a committee to select the first Dean of the reopened school.

There is another relationship which I had with Jack in a field entirely foreign to the law. Beginning about 1940, or perhaps earlier, my wife and I became annual subscribers to the Tuesday Night Series of concerts of the Boston Symphony Orchestra. Our seats were directly behind the seats in the immediate row ahead occupied by Jack and Jacqueline Spalding, and so for a period of some thirty years, we four in effect attended the Tuesday Night Series of concerts together. Jack, because of the musical interests of his mother and his training as a violinist, was the one with the most musical knowledge of the four of us. He also had a great knowledge of the composers and their lives. I had the opportunity over those thirty years to see that he was not narrowly confined to the law and to see just how broadly cultured a person he was.

In his final years, when he was in a nursing home confined to a bed, his right side completely paralyzed, I visited him often and brought him books to read as long as his eyesight permitted him to read. Each time I came to see him we talked for an hour or so. I can testify to the quiet courage he showed in accepting the disasters which had befallen him, not only his own devastating stroke, but later the illness and death of his wife. I can also testify to the clearness of his mind and memory which lasted through the last time I saw him.

As a lawyer John Spalding exemplified in the highest degree all those qualities of excellence we hope to find in a lawyer; as a judge he exemplified in the highest degree all those qualities of excellence we hope to find in a judge, and as a man he exemplified in the highest degree all of those qualities of excellence we hope to find in a man.

I feel honored to have this opportunity to join in the request for the allowance of the motion before this court.

William J. Pechilis, Esquire, addressed the Court as follows:

As a former law clerk of Justice John V. Spalding, I would like to put on the record a few of my recollections of him as a teacher and as a friend.

The first impression that comes to mind is the deep sense of humility which permeated Judge Spalding's approach to the law and his relationship with his law clerks. From the outset, notwithstanding the fact that he was a member of this historic and preeminent court, he made it clear that he considered himself a student of the law and that he regarded his law clerks as partners working with him on the common task of putting together an opinion.

Equally memorable was Judge Spalding's complete lack of pedantry, a trait which is reflected in the conciseness and directness of his opinions. I can still hear his constant admonition to "go for the jugular" and to avoid issues not essential to the disposition of the case at hand. For him, going for the jugular also meant writing memoranda and opinions with language that was both forthright and precise.

With Judge Spalding's patient and sage counsel, his law clerks soon developed a proficiency in marshalling the facts of a case, identifying issues, analyzing legal precedents and writing a reasoned memorandum of law. For the Judge, however, the law was much more than legal craftsmanship; he also imparted to his clerks a deep concern for justice and the fairness of the legal process.

From their close association with Judge Spalding, his law clerks quickly came to realize that reading and writing law with him was not a cheerless endeavor. I recall, for example, his characterizing a difficult opinion as tantamount to casting a stone at a double pane window with the objective of breaking only the interior pane. I also recall that when deciding a case which was utterly without merit, he likened the construction of his opinion to the simple lines of a plain pine coffin. And when assembling and rearranging a draft opinion with scissors and paste, he would refer constantly to his "tonsorial and agglutinative" agility.

In addition to being a teacher, Judge Spalding was a friend who took personal interest in his law clerks and at all times was a resource for them with encouragement and counsel both during and after their careers as clerks.

Serving under Judge Spalding bestowed a double benefit -- first, the acquisition of legal skills in the highest professional tradition; second, and more important, the realization that one's life had been touched by a great man.

The Chief Justice said:

Mr. Attorney General, Members of the bench and bar, ladies and gentlemen:

I have asked my former associate, Mr. Justice Cutter, now retired, to reply for the court to the addresses made this morning by the Attorney General and other members of the bar.

Justice R. Ammi Cutter addressed the Court as follows:

Mr. Chief Justice: I am grateful to you and to the court for the opportunity to speak for the court at this session in memory of Mr. Justice Spalding. To him I am indebted for over sixty years of friendship and kindness. It was my good fortune to serve with him here for some fifteen years, and to receive from him, as did others, generous guidance in learning and applying the traditions and practices of this bench.

When I was appointed in 1956, Mr. Justice Spalding had been on this court for over twelve years. He had sat here with great judges, and was anxious that all who came here should share his and their high standards of judicial performance and diligence. He took pride in the reputation of this body and strove constantly to enhance it. From college days on, I had known and respected his character and qualities. Working with him here, however, gave me new appreciation of his merits. From discussions in the consultation room, I gained further admiration for his extraordinary detachment and objectivity, for his insistence on integrity of reasoning, and for his own learning and thoroughness. He had been here long enough to have seen precursors of many cases which came before the court in my day. His fine memory often enabled him to recall precedents not mentioned in briefs or arguments. Frequently he pointed out problems not sufficiently developed by counsel. At the initial discussion of a case following argument, after he had analyzed the issues, others on the court usually had an expanded understanding of the questions presented.

Reference has been made by the Attorney General and others to the Justice's concise opinions. That he wrote as he did was not accidental. He worked hard to be succinct and clear. He tried always to confine his opinion to those matters which it was then necessary for the court to decide. He used footnotes sparingly and did not like them, even in the opinions of others. This I discovered rapidly, somewhat to my chagrin because I found them useful. He recognized, however, that others were entitled to reasonable leeway in matters of literary taste.

Every appellate court should strive to conduct its business as a team and Mr. Justice Spalding was, in every respect, a team player. His colleagues found him constantly helpful when they encountered difficulties of analysis or research. In consultation, he had a sharp eye for faulty reasoning or misinterpretation of precedents. Often he suggested felicitous improvements in substance and style. When an opinion received his assent, the author could have a comfortable feeling that his handiwork had withstood scrutiny by a most competent and conscientious critic. In every respect, he was a cooperative, supportive colleague, but one who retained fully the independence of forceful dissent, when a reconciliation of honestly-held, but differing, views could not be achieved. He was a perceptive and warm friend of each one of us.

Because he had earned the respect of his colleagues, Mr. Justice Spalding's views carried unusual weight in shaping the law of the Commonwealth for over a quarter of a century. The members of the court had confidence in his judgment. They knew that the bar shared that respect. For precedent he had due deference, because he recognized the importance of stability and predictability in the law. In changing times, however, he was prepared to reexamine, and where appropriate to modify, old decisional law. In procedural matters, he led the Rules Committee in necessary changes. He had a large share in assuring that, in his time, the court moved with wisdom, flexibility, and good sense.

Memorial exercises like these are not primarily to mourn the loss of a valued colleague and beloved friend. They are designed instead to record and to express gratitude for the contribution which has been made by the one who has gone. What has been said today shows that the contribution of Mr. Justice Spalding was very great indeed.

Mr. Chief Justice, I recommend that the Attorney General's motion be allowed.

The Chief Justice said:

We allow the motion that the Memorial presented by the Attorney General be spread upon the records of the court.

The court will now adjourn.