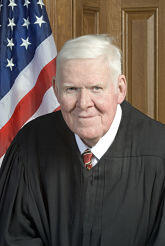

Kent B. Smith

Associate Justice memorial

84 Mass. App. Ct. 1137 (2013)

A special sitting of the Appeals Court was held at Boston on November 19, 2013, at which a Memorial to the late Justice Kent B. Smith was presented.

Present: Chief Justice Rapoza; Justices Cypher, Grasso, Kantrowitz, Berry, Kafker, Cohen, Green, Trainor, Graham, Katzmann, Vuono, Grainger, Meade, Sikora, Rubin, Fecteau, Wolohojian, Milkey, Hanlon, Carhart, Agnes, Sullivan, and Brown; Supreme Judicial Court Chief Justice Ireland; Supreme Judicial Court Justices Spina, Cordy, Botsford, Gants, Duffly, and Lenk; retired Supreme Judicial Court Justices John M. Greaney and Judith A. Cowin; retired Appeals Court Chief Justice Christopher J. Armstrong; and retired Appeals Court Justices Rudolph Kass, Raya S. Dreben, George Jacobs, Mel L. Greenberg, Kenneth Laurence, William I. Cowin, James F. McHugh, and David A. Mills.

Martha Coakley, Attorney General, addressed the court as follows:

May it please the Court: As the Attorney General of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, it is my honor to present, on behalf of the bar of this Commonwealth, a memorial and tribute to the late Kent Smith.

Justice Smith was first appointed to the Superior Court by Governor Francis Sargent in 1972 and to the Appeals Court by Governor Edward King in 1981. He served as an Associate Justice until his mandatory retirement in 1997 and then served as a recall justice until 2012.

He authored more than 1,500 appellate decisions during his long tenure and, by his own estimate in a 2010 interview with Lawyer's Weekly, screened a further 10,000 criminal cases.

Described by that publication as "A walking encyclopedia of criminal law," he authored the widely cited, three volume Criminal Practice and Procedure of the Massachusetts Practice Series. Originally published in 1970, his passion for the criminal law as "the man who wrote the book" continued through three editions and more than twenty supplements of that treatise.

He was a legal scholar known for correctness, clarity and fairness and was cited several times as a respected authority by the U.S. Supreme Court. He taught at Western New England Law School, numerous MCLE programs and received numerous awards.

Justice Smith's tenure on the Court was not only long and fruitful, but he was also highly valued and admired by those he worked with. Justice R. Marc Kantrowitz spoke for many when he stated, "I really learned a lot from him about the law, history and how to carry oneself." His co-workers especially appreciated his quick wit, sense of humor and cheerful disposition. Justice Elspeth Cypher fondly remembers, "He literally used to walk through the halls whistling and singing . . . if he saw someone he knew, he'd sing a lovely little tune to them."

Justice William Cowin remembers his former colleague as “one of the most decent human beings” he had ever encountered. On Justice Cowin’s first day at the Appeals Court, Justice Smith went out of his way to find and welcome him. Part of that welcome was a detailed recollection of a case that Justice Cowin had tried before him decades before. From that moment on, Justice Smith remained a source of friendship and support.

Justice Smith had a long and distinguished career in private practice before his appointment to the bench. After graduating from American International College and Boston University School of Law, where he was on the Law Review, he maintained a civil and criminal practice in the Springfield area from 1953 to 1972. In 1954, he became the first public defender in Western Massachusetts as a member of the Voluntary Defenders Committee, a predecessor of the current Committee for Public Counsel Services. He went on to represent more than 500 criminal defendants, including eighteen accused of murder.

He was an avid reader, particularly of spy novels and history, to the point where he would critique new releases for a Springfield bookstore which then promoted his recommendations. An enthusiastic traveler, he especially enjoyed visiting London and other European locations associated with the Second World War. In the course of this travels he met both Pope John Paul II and Paul McCartney; some have suggested he may have attempted to sell his book to both of them.

Although he was dedicated to it, Justice Smith’s life did not just revolve around the law. He was devoted to his family. With us today is his wife, Marguerite (Peg) Smith; his two daughters Barbara Carra (and husband Victor); Margaret Kennedy (and husband Thomas); brother, David Smith; grandson, Victor James Carra, II; and granddaughter, Margaret Rose Kennedy.

Justice Smith occupies a special place in the history of this court. As Chief Justice Rapoza has stated, "Regardless of the many capable justices on this court, both now and in the future, there will never be another Kent Smith."

On behalf of the Commonwealth, I respectfully move that this memorial be spread on the records of the Appeals Court.

John J. Egan addressed the court as follows:

May it please the Court: Mister Chief Justice, and Judge Smith’s brothers and sisters on the Appeals Court, and Peg, Barbra, and Margaret, my thanks to you for your kindness in allowing me to support the Attorney General’s motion on behalf of the bar and in particular the bar of the Western part of our Commonwealth.

The law for Justice Smith, Mister Chief Justice, was not merely his profession, it was his passion. It was his way to live out those principles of human dignity and justice first embedded in him at home by wonderful parents, nurtured by educators at AIC and BU Law School, and of course, encouraged by his strongest supporters, his wife Peg and daughters Barbra and Margaret. He saw being a lawyer and then a Judge as the best way to live out that passion. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., wrote that, “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.” That was the ethos by which Kent B. Smith lived his life.

Admitted to the bar in 1953, Kent Benedict Smith’s early career was marked by his firm belief in justice for all. He became the first “Voluntary Defender” in the four Western Counties. As a sea change in criminal practice and procedure took hold driven by U.S. Supreme Court cases like Gideon, Mapp, Miranda, Katz, and their Massachusetts progeny, Kent Smith stood beside countless indigent defendants as their sole advocate and protector. It was a heady time for the criminal defense bar. Often, Kent Smith was the very first lawyer to integrate what are now accepted principles of constitutional protection into the gritty reality of defending poor and friendless individuals charged with the most serious crimes.

During the time from 1953 to 1972, he also settled into a busy private practice. He and his partners, Ben, Tom O’Connor, and Tom Martinelli, were some of the finest trial lawyers in Springfield. Although his practice was substantially devoted to criminal matters, he handled a wide variety of other matters.

He was, for years, a highly respected and skillful labor lawyer and negotiator. He served as General Counsel to the Western Massachusetts Chapter of the National Electrical Contractors Association. Those companies marveled at his skill in negotiations that were often tense. His success was not simply the product of his knowledge of labor law. Rather, it was the result of the way he treated people. He had absolute credibility with the other side because they knew he was incapable of deception. He used reason and warmth to bridge gaps initially thought impossible.

Kent Smith made no secret of his desire to be a Judge. He wasn’t coy about it. He pursued it for all the right reasons. I recall a busy day in the Springfield District Court during the morning recess when he left a group of his contemporaries who were gossiping. I was, as a young public defender, allowed to hang around and listen. He said to his friends, “Now fellows, watch this.” He ascended to the Bench, sat down, peered over at them and said, “Boys, someday, someday, so get used to it.” Then he laughed at the cat calls from the group. During the later part of his private practice, he was sought out by West Publishing and asked to put his encyclopedic knowledge of Criminal Practice and Procedure into writing which became Mass. Practice Volume 30. It was a compilation of all the information he had been generously sharing with young lawyers like me as we made our way. Always dispensed graciously with a dose of practical information on how to best serve our clients. First published in 1970, it is now the bible of Massachusetts Criminal Practice and Procedure and has grown to three volumes. He was so proud that he was able to write it and then improve upon it year after year. He was quick to tell his friends to make certain they bought each new volume and supplement. He had, he would say, “kids to educate and trips to take.”

In 1972, now a seasoned trial lawyer and author of an important treatise, he was selected as an Associate Justice of the Superior Court by Governor Francis Sergeant. He settled in with grace and ease. He was a joy to try in front of: always prepared, always listened, always cordial, and always curious. His colleagues would talk of his collegiality and willingness to share his vast criminal expertise. The trial bar would pay him their highest compliment, “He hasn’t changed a bit.” He was particularly helpful to young women beginning to navigate their careers as trial lawyers. I believe his career as a trial judge is best reflected in the words of Sir Thomas Noon Talfourd, the Nineteenth Century English Judge and author. These words are engraved on the main entrance to the Hampden County Hall of Justice. I quote: “Fill the seats of Justice with good men, not so absolute in goodness as to forget what is human frailty.” He reveled in being a trial judge.

Mister Chief Justice, 1981 was a happy year for Justice Smith and a bittersweet year for the trial bar in the four Western Counties. He was appointed to the Appeals Court by Governor Edward J. King, and we lost one of our most able trial judges. Here on this Court, he joined his friend from Springfield, Justice Greaney, and he found a home -- a home for the next thirty years. He loved the collegiality of the Court. The position of an Appellate Judge suited him so well. First, he loved to read and research. He used his opinions not only to resolve the issue but to explain and teach so that the bar and trial courts could take something more from the opinion. At oral argument, he was curious and kind, probing counsel’s rationale but never embarrassing them even when it was apparent their arguments would not withstand scrutiny.

In a tribute to the high esteem in which he was held, and I believe as a reward for his scholarship and collegiality, he was appointed and reappointed as a Recall Judge. He simply couldn’t get enough of this Court and all of you. Those recall years were a special gift to him and to all who benefited from his wisdom and warmth -- fellow Justices, law clerks, staff, the bar, and the citizens of this great Commonwealth.

Mister Chief Justice, surely that remarkable professional career would be a grand legacy for any individual, but it is only one of many dimensions of Kent Benedict Smith.

As passionate as he was about the law, he was more passionate about his family. He and Peg were rightfully so proud of Barbra and Margaret as young women, as accomplished professionals, and as loving mothers. In my judgment, the tribute most important to him listed in his obituary had nothing to do with his professional achievement rather it was the phrase that he was survived by two “grateful” daughters. He wasn’t a great fan of the beach, but because of the joy it gave Peg, Barbra and Margaret, they purchased a home at Groton Long Point, Connecticut, where the family enjoyed many summers. In the summer afternoons, when the girls were with their friends and Peg would sneak out for an hour of well-earned solitude on the beach, he would sit on the porch, out of the sun, reading appellate records or drafts. If I was walking by, he was always open to some of the latest political rumors or bar gossip.

He was elated when his grandchildren, Jay and Margaret Rose, came along. He had enormous fun with the fact that his grandson was born on Christmas Day. Remarking that in all of history Jay was the second most remarkable male born on that day. He and Peg enjoyed the freedom of travel after the girls were launched. His descriptions of the battlefields and cemeteries in Normandy were riveting and reverential. Of course, he loved to read…anything, nonfiction, fiction. He enjoyed spy novels. He was such a great consumer of the written word that a bookstore in Springfield used to assign him a table on which he selected the books to be displayed. A small sign was placed on the display which read, “Recommended by Kent Smith.” He would be found there almost daily at lunch time browsing, and if you were in the store, he would dispense with his recommendations. “Hey, kiddo, you will love the tradecraft in this one.” Before Amazon, Nook, or Kindle, he spent a small fortune on actual books. Many of those once read, and perhaps with a gentle push from Peg to get them out the house, were donated to the Longmeadow Town Library, a place where he spent many happy hours.

In addition to his family, his character and values were a distinct product of his deep religious faith. He and Peg started their day at Mass. He often remarked it was a great way to start the day. He then proceeded to act on that faith for the balance of the day. But that wonderful sense of humor was always at work. If I was there for a week because one of my sons was serving the 7:00 Mass that week, on Friday, when he knew I would not be back the following week, he would say, “Jack isn’t this a great way to begin the day.” I would agree and he would continue, “You know we’re going to do it again all next week. In fact, we do it all year.” All with a big smile.

When he was selected to receive the Saint Thomas More Medal from the Saint Thomas More Society that covers the four Western Counties, I congratulated him. He was very gracious, but before we parted, he smiled and said, “Jack, tell the boys, Worcester gave me theirs two years ago.”

I believe, Mister Chief Justice, Kent Benedict Smith was an extraordinary lawyer and Judge because he was first an extraordinarily centered man with a deep understanding of the majesty and frailty inherent in each of us.

Mister Chief Justice and Members of the Court, we in the four Western Counties believe we have sent this Court our stars. Beginning with:

John M. Greaney, Associate Justice (1978-1984); Chief Justice (1984-1989);

Kent B. Smith, Associate Justice (1981-1997); Recall Justice (1997-2012);

Elizabeth A. Porada, Associate Justice (1990-2003); Recall Justice (2003-2004);

Francis X. Spina, Associate Justice (1997-1999);

Ariane D. Vuono Associate Justice (2006 - present); and

Judd J. Carhart Associate Justice (2010 - present).

That is a list of wonderful, talented men and women—our all stars.

But I believe Kent Benedict Smith to be the North Star. The one that shines brightest in the sky and the one that provides a mark by which all can navigate their way -- the way of scholarship tempered by kindness and humility.

I want to close by going to the source. Mister Chief Justice, these are the words of Kent B. Smith, Associate Justice of this Court, spoken on June 24, 2003, at the memorial session of this Court in honor of the late Chief Justice Joseph P. Warner. I will take the liberty of substituting Justice Smith’s name for Chief Justice Warner because in the last analysis Justice Kent Benedict Smith best expresses our feelings so well. So I quote from 58 Mass. App. Ct. 1115, at 1139 (2003):

My final words are these: Kent B. Smith was our dear friend, and I have struggled to find adequate words to describe this good man. There are words, however, in the Book of Daniel in the Old Testament that I believe convey my thoughts and indeed the thoughts of his brothers and sisters of the Appeals Court in regard to the life of Kent B. Smith. In Chapter 12 of the book, Daniel describes the ideal world. He wrote: ‘The learned will shine like the brilliance of the firmament and those who train many in justice will sparkle like the stars for all eternity.’ And that is what our brother Kent did -- by his life and example, he trained many in the ways of justice. Truly, he will sparkle like the stars for all eternity.

Mister Chief Justice, I and the Bar of Massachusetts, and in particular Western Massachusetts, strongly recommend that the Attorney General’s motion be allowed.

Catherine W. Koziol addressed the court as follows:

May it please the Court: Chief Justice Rapoza, Associate Justices of the Appeals Court, Mrs. Smith, the Smith family and guests, it is an honor and privilege to speak today on behalf of Justice Smith’s law clerks and in support of the Attorney General’s motion. In preparing my remarks, I sought the input of several of Justice Smith’s many law clerks and the consensus was that Justice Smith was a mentor, teacher, advisor and supporter of all of us.

In late July of 1996, when I interviewed with Justice Smith, I had been a lawyer in private practice nearly four years. At that time, he was sixty-nine years old. He offered me a job as his law clerk making sure I understood that he may no longer be an Associate Justice of the Appeals Court after March 11, 1997, when he reached the mandatory retirement age of seventy. I gladly took the job with this understanding as I couldn’t imagine anyone passing up the opportunity to work for him, even if it were just for a couple of months. Fortunately, Justice Smith remained on the bench for the next fifteen years.

As Justice Smith’s law clerks, we felt that we were doing something socially relevant and performing work that really mattered. His encyclopedic knowledge of the criminal law and procedure wowed us all. If you reached an impasse in preparing a bench memorandum and went to discuss the problem with Justice Smith, invariably he would recite the volume, page, and usually the author of a decision that, either would solve the problem immediately, or lead you directly to another case that would. His innate, spot on understanding of the frailties of human character, and his practical view of the way people work and live in the world, was infused in his decisions.

Justice Smith’s decisions are immediately recognizable by their clear language, concise and fluid style. Clearly, he was a gifted writer. Justice Smith was acutely aware that his opinions and his treatise on Criminal Procedure were his legacy. For Justice Smith, opinion writing was an enjoyable work in progress. No matter how long he worked on an opinion, he loved every second of that work, and it showed. He almost always had the radio on and often sang or whistled while he worked. It was a sheer joy to see. Each new opinion was as important to him as the last, and he took great care to work and rework those opinions until they passed his high standards. Draft upon draft, Justice Smith literally cut and pasted long before any word processing program was developed. It was his law clerk’s job to edit, Shepardize, and compare the newly typed version that his administrative assistant produced, with that draft. This process was repeated multiple times for each decision. By engaging his law clerks in this process, he taught us that it took patience, thorough research, and just plain hard work to analyze and concisely articulate the proper resolution of every issue. Once his decision was published, he kept a watchful eye on it, taking great pleasure in telling his clerks when further appellate review was denied! Whenever the press ran a story about one of his decisions, he painstakingly clipped it out of the newspaper to share with his law clerk. If the law clerk who worked for him at the time he wrote the decision was no longer working for him, he would send the clipping to that clerk, with a note concerning how the decision was playing in the local press.

Fiercely loyal to, and proud of, western Massachusetts, Justice Smith was an avid champion of all the lawyers and judges who work in our region. His care and affection for the bars in the four western counties and his devotion to the local law school meant that he selected many of his law clerks from Western New England College School of Law, or our community at large. His generosity of his time, talent for making things happen, and vision for each of us was the common thread that tied us together as his law clerks. To Justice Smith, we were all “kid,” and even though we knew we shared that moniker with all of his other law clerks, he had a special way of making you feel like it was exclusively your nickname.

One thing that I don’t think any of us were prepared for, or had even dared to imagine, was that once you became Justice Smith’s law clerk you became part of his extended legal family, for life. His law clerks, as much as his decisions, were his works in progress and he took great care to attend to us on a regular basis. He never stopped trying to help his former law clerks, seeing the potential in each of us, even when we did not see it ourselves, and encouraging us to reach the top of that potential. He reveled in each of our accomplishments, and if he thought we weren’t progressing as we should through our careers, he would give us a gentle push. Justice Smith kept his ear to the ground and would call former law clerks if he heard of any employment opportunities in the legal field that he believed suited that clerk’s abilities and career objectives. He was always accessible, ready to listen and then lend his sage advice. He was never ashamed to say he didn’t know the answer to a question that you asked, but that he would get back to you after thinking about it, which of course, he always did.

Justice Smith had an irrepressible joy for life. He loved celebrating when his law clerks passed the bar and he loved celebrating Christmas. He also loved his birthday, and because of that love, countless law clerks, staff members and Justices from the Springfield office benefited from the yearly banquet of pizza and birthday cake. Although he liked pizza, Justice Smith was most happy in his later years when Justice Vuono joined the Court and infinitely improved upon the menu by substituting the pizza with homemade pasta with Bolognese sauce. I came to realize that Justice Smith’s love for his birthday was not about him, as much as it was his way of seeing to it that we all got together as a group. He knew that doing so helped to solidify the understanding that even though we were his law clerks, we were making a contribution to the larger team endeavor that is the hallmark of the Massachusetts Appeals Court.

Justice Smith strove to ensure that the public had confidence in the judiciary and an appreciation for the work that the Court did. As a result, he was especially happy on the days that the Court was scheduled to sit in western Massachusetts at the Western New England College School of Law, or at the grand old courtroom in the Hampshire County Court House. Appeals Court sittings in Western Massachusetts made Justice Smith happy because they gave local law students, lawyers and the public the opportunity to see the court in action.

It is no secret that Justice Smith is a legend and celebrity in Hampden County, or that his gifts of quick wit and humility were disarming. Watching him in action was a lesson in civics that few people get to see, but one that most people could benefit from. People from all walks of life loved him for who he was, not what he was. As his former law clerk, Charles Stephenson so eloquently put it, “[m]ost of all, Justice Smith was the consummate judge, because he was a person first, husband and father second, lawyer third, and judge last, understanding that he, no less than the rest of us, was an imperfect soul, which caused him to treat everyone with dignity and genuine respect."

This brings me to my last and most enduring memory of Justice Smith. He possessed the gift of great faith. As a devout member of the Catholic Church, Justice Smith’s religion was the cornerstone in his life’s foundation. He was an early riser and liked to attend early morning Mass at his beloved St. Mary’s in Longmeadow, prior to going to work. As a result, it was nearly impossible to arrive at work before Justice Smith. Most mornings I would arrive to the sound of Justice Smith whistling or singing in his office either writing away, yellow legal pad in hand, or sitting back in his chair, deep in thought, renewed by his daily devotion. When I think of Justice Smith, I think of a verse from the Bible, which I believe summarizes how he lived his life. The passage is from the book of Micah, Chapter 6 verse 8: “He has showed you, O man, what is good; and what does the Lord require of you but to do justice, and to love kindness, and to walk humbly with your God?” Justice Smith did those things every day of his life. His love and concern for his fellow man was palpable, his humility was ever present, even in his carefully timed plugs for his book and his not so gentle reminders, always made with a smile on his face and gleam in his eye, that March 11, his birthday, was right around the corner, and he unquestionably made significant and lasting, positive contributions to the law and society, one decision and one law clerk at a time.

On behalf of all of Justice Smith’s law clerks, I join in supporting the Attorney General’s motion.

Justice Cypher, speaking for the court, responded as follows:

Mister Chief Justice, thank you for inviting me to speak on behalf of the Appeals Court in response to Attorney General Coakley’s motion.

Kent B. Smith, a Justice of this Court, passed from this life on October 31, 2012. These memorials are designed to record and express gratitude for the contribution which has been made by the one who is gone. In this way, future generations who did not know Justice Smith will learn by this record of the great contributions that he made to the Appeals Court and to the laws of the Commonwealth. Of course, Justice Smith’s contribution to the Commonwealth was so great that future generations will also learn of him by reading his cases, by reading his book, and by appearing before the Judges and Justices who have been educated by him. This memorial will also serve to record his fine personal qualities of compassion, kindness, humor, intelligence, and humility. Justice Smith loved his family, his friends, his court, his country, his religion, and the law. Every action that he took, every word that he spoke, served to exalt those and what he loved.

Justice Smith’s judicial scholarship was legendary and without equal. His opinions were models of organization and sharp analysis. His writing was perfect: concise, clear, and devoid of idiosyncratic vanities. In fact, while preparing for these remarks, I searched his written opinions for language of his that could serve as a quotation that expressed his essence, character, and intellect. That I could not find a single word in any of his opinions that did not directly bear on the case at hand is the best tribute that I can think of. He did not use the bench as a tool for his purposes; rather he served the purposes of Justice.

In addition to his fine appellate opinions, he literally “wrote the book.” His volumes of the Massachusetts Practice Series on criminal practice and procedure organized and explained this important and deceptively complex area of law. Justice Smith’s work has been relied on by scholars, law students, law clerks, lawyers, and judges.

As an attorney, I loved to argue before Justice Smith. Every time I did, I walked away smarter and taller, and more and more charmed by this delightful man. And, on one occasion when I overlooked an important case, he let me know about it in a gentle and teasing manner. Of course, when I joined the court, he often reminded me of this event in a good natured manner, and it became our private joke. It also served as a reminder to both of us that in that particular case we shared a deep compassion for the defendant and for his situation. Justice Smith embodied many wonderful qualities, one of which was an exquisite sensitivity.

Justice Smith was a joy to sit with. On the bench he asked the hard questions, but he never, ever used his position or quick wit in a way that embarrassed an attorney. He did not pursue pointless theoretical questions at the expense of those sitting with him or arguing before him. He did not attempt to demonstrate his superior knowledge. He did not argue with the lawyers. Instead, he used his time to skillfully elicit the important legal principles and make muddy problems appear as if they had always been completely clear. And to him, they were. He always treated the lawyers with the greatest respect, even when correcting them.

At semble, the time after oral argument when the three judges on the panel sit behind closed doors to discuss the case and its resolution, Justice Smith was always willing to listen and consider a different point of view. He was not rigid in his views and he was always polite and patient, even with those of us with far less experience and knowledge.

Justice Smith once observed that there is more to being an excellent Appeals Court justice than one’s own decisions. He believed that collegiality was an important quality. And he taught that to us all by example. Justice Smith explained that collegiality meant “more than getting along with one’s fellow justices. It means being a team player to make sure that all of the opinions issued from the court are of the highest quality.” Justice Smith was always available to anyone to discuss a difficult legal problem. He kept his politics to himself and he never publically criticized a member of the court. He personally welcomed every new member of the court and was truly happy to have them on the court and claim another friend.

Every opinion of this Court is read by all of the justices before it is published. This feedback, and the dynamic exchange that it creates among the justices, makes every opinion a better opinion. Justice Smith was one of the best contributor’s to this process. He took the time to read each opinion carefully and provided thoughtful and helpful suggestions. It was a thrill to receive a comment back from him such as “good job, kid.” It was equally devastating to receive back “what are you talking about? This makes no sense.” Of course, these comments were accompanied by helpful suggestions. If it was a really bad review from him however, it was delivered by telephone or in person. Again, his personal touch made it an educational and even enjoyable experience.

Justice Smith also contributed to the education of all of the judges of the Commonwealth, teaching with his dear friend Justice Greaney every year at a judge’s seminar. Justice Smith was also the kind of jurist who kept learning, not content to rest on already acquired knowledge. On the rare occasion during the second panel process when faced with a new term of art, even if it contradicted his frame of reference, he soon accepted it and incorporated it into his vocabulary.

Justice Smith’s presence at the Appeals Court had a far greater reach than the courtroom and the reporter’s book of opinions. Throughout his time at the Court, he frequently walked through the halls whistling lovely melodies and stopping to talk to everyone he saw. And every time he did, that person’s step was a bit lighter and their eyes a bit more bright.

When he taught me his secrets for screening the criminal cases, he insisted that one of the most important parts of the process was to personally return the briefs to the clerk’s office and greet each member of the office. He would not be happy with our computerized process that diminishes our contact with each other. To walk across the plaza with him to pick up lunch required an extra fifteen minutes to account for all of the people who stopped to talk to him. And even when he could not easily handle the walk, he insisted on picking up his own lunch so that he could see his fans.

I consider myself fortunate to have learned from him, to have worked with him, and to call him a friend, advisor, and mentor. He once shared with me one of his favorite prayers, written by Franciscan priest Father Mychal Judge, who was killed on 9/11 at the World Trade Center when he was ministering to a fallen firefighter.

Lord, take me where you want me to go.

Let me meet who you want me to meet.

Tell me what you want me to say,

And keep me out of your way.

No matter whether one shares his religion, or is of no religion, we can all appreciate these words as a window into Justice Smith’s heart.

Socrates said, “Four things belong to a judge: to hear courteously, to answer wisely, to consider soberly, and to decide impartially.” Justice Smith fulfilled these ideals. In doing so, he set an example for all of us on the Appeals Court. His portrait hangs on the wall facing us while we are on the bench. May it always remind us of the ideals he embodied and the compassion he showed to every person who crossed his path.

Mister Chief Justice Rapoza and fellow members of the panel, I recommend that the Attorney General’s motion be allowed.