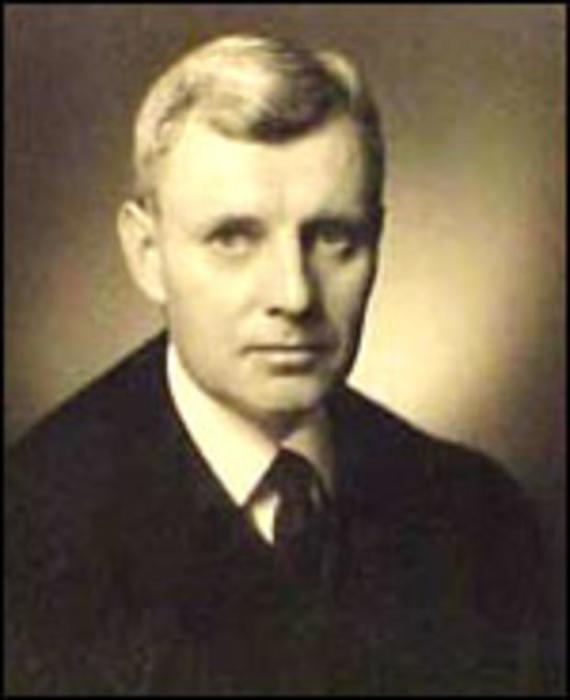

Richard Ammi Cutter

Associate Justice memorial

418 Mass. 1603 (1994)

A special sitting of the Supreme Judicial Court was held at Boston on September 14, 1994, at which a Memorial to the late Justice Richard Ammi Cutter was presented.

Present: Chief Justice Liacos; Justices Wilkins, Abrams, Nolan, Lynch, O'Connor, and Greaney; retired Chief Justice Edward F. Hennessey; retired Justices Francis J. Quirico and Benjamin Kaplan; and Chief Justice Joseph P. Warner, of the Appeals Court.

L. Scott Harshbarger, Attorney, General, addressed the court as follows:

May it please the court: As the Attorney General of Massachusetts, it is my privilege and honor to present, on behalf of the Bar of this Commonwealth, a Memorial and tribute to the late Richard Ammi Cutter, who served as associate justice of this court for sixteen years.

Richard Ammi Cutter was born in Salem on May 11, 1902, the son of Louis Fayerweather and Mary (Osgood) Cutter. He died in Boston on November 28, 1993, in his ninety-second year. He is survived by his sons Louis and Henry and his daughter Helen Maclennon. His wife Ruth predeceased him.

Ammi Cutter was graduated from Noble and Greenough School, which was then located in Boston, after which he entered Harvard College. Upon his graduation in 1922, he went on to Harvard Law School where he earned his law degree as a member of the class of 1925, serving in his final year as an editor of the Harvard Law Review.

He later served as the president of the Harvard Law School Association, as chairman of the Overseers' Committee to Visit the Harvard Law School, and as a director of the Harvard Alumni Association, as well as a member of the Board of Overseers of Harvard College. In 1979, Harvard awarded him an honorary Doctor of Laws.

After his graduation from law school in 1925, Ammi, as his parents chose to refer to him, embarked upon his legal career as an associate in the Boston firm of Goodwin, Procter & Hoar. In 1927, he began three years of service as a Massachusetts Assistant Attorney General, trying tax cases and arguing appeals before this court. For most of the years between 1930 to 1956, he maintained a diverse general practice at the firm of Storey, Thorndike, Palmer & Dodge. During World War II he left his practice to join the military. This tour of duty, which saw Justice Cutter ascend from the rank of Major in the Army to become an aide to the Assistant Secretary of War, earned him the Legion of Merit with one oak leaf cluster. His duties with the Assistant Secretary's office included planning for the military governments in Germany and Japan, researching war crimes prosecutions, and looking at issues regarding treatment of American prisoners of war in enemy hands.

After the war Ammi returned to his law practice. His work in the private sector ended in 1956 when he was appointed by Governor Christian A. Herter to this court. He sat as associate justice of the Supreme Judicial Court for sixteen years until his retirement, in 1972, at the age of seventy.

During his tenure on this court, of the 630 full opinions he authored, a mere fourteen elicited dissent from his brethren, evincing the measure of his influence. His opinions, noted for their details, depth of analysis, and often extensive footnotes, were always well focused and never ornate. One of his most important and widely cited opinions is Commonwealth v. Freeman, 352 Mass. 556 (1967). In Freeman, Justice Cutter wrote for the court that in cases in which there is a substantial risk of a miscarriage of justice, technical procedural barriers would not deny appellate relief to defendants. In his refusal to place form over substance, Ammi Cutter, in this case, as in many others, worked to ensure that our judicial system met its often hard-to-realize goal of dispensing justice.

Justice Cutter's retirement from the court in 1972 proved to be short-lived; he was appointed soon after by the United States Supreme Court as master of original jurisdiction in an action between New York and Vermont concerning alleged pollution in Lake Champlain. In 1980, at the age of seventy-eight, he was recalled to the Massachusetts Appeals Court, where he was to serve ten years. During that time he handled a workload encompassing the full legal spectrum and authored an additional 143 opinions. His exceptional contribution to the Commonwealth was recognized in 1984 when Justice Cutter was awarded the Boston Bar Association's Public Service Award.

His tenure on the bench embodies all the best aspects of public service; it demonstrates the reasons that I encourage young lawyers to enter public service; he dealt with all of the important issues of his day from defendants' rights to First Amendment rights and literary expression; he took his opportunities to right the wrongs that he saw; and he used the law -- always with a great respect for precedent, but employing his creativity to fashion innovative remedies -- to bring a little more justice to the world. In a time, such as the present, when the law has, for too many people, come to represent not simply the minimum ethics: What "Thou shall NOT do," but the maximum ethics: "it doesn't matter if it's wrong as long as it's not illegal." Justice Cutter's life and his work serve to remind us that public service and the law have a nobler purpose.

While Justice Cutter's contributions on both the Supreme Judicial Court and the Massachusetts Appeals Court merit high praise, his legacy reaches beyond simply his judicial opinions. Justice Cutter's election on February 24, 1938, to the American Law Institute was the beginning of a tenure at the Institute that was to last five and one-half decades. His responsibilities included second vice president, first vice president, and, in 1976, president of the Institute. In 1980, he became chairman of the Council, a post which he held until 1987, when at the age of eighty-five, he assumed emeritus status. Throughout his active and lengthy membership, Ammi served as an advisor on many projects of the Institute, including the Restatement (Second) of Property; the Restatement (Second) of Conflict of Laws; and the Model Land Development Code. These many years of devoted service prompted the Institute to name its First Reporter's Chair for Ammi Cutter.

Perhaps the achievement for which Justice Cutter would be most proud, however, rests in his countless efforts to advance the lives and careers of those individuals fortunate enough to know and work with him. Although examples of his efforts on behalf of others are numerous, this trait is exemplified by Benjamin Kaplan's experience with Ammi Cutter at the Pentagon, to which I understand Judge Kaplan will refer in his remarks. Similar efforts laid the foundation for the careers of numerous lawyers and judges and one Governor -- William F. Weld.

Justice Cutter's typically understated reflection on his own career that "occasionally there is a basis for feeling that one's work contributes a little to progress" is based on much more than the many judicial opinions and statutory codifications on which he has left his indelible mark. The progress advanced by the work of Justice Cutter has taken form in the careers and achievements of the innumerable individuals who, perhaps unbeknownst to them, have had their careers advanced, their lives enriched, and obstacles in their paths removed by this kind, intelligent, and decent man.

It is an honor for me to participate in this fitting ceremonial to an outstanding Justice of our Supreme Judicial Court and a man worthy of great respect.

On behalf of the Bar of the Commonwealth, I respectfully move that this Memorial be spread on the records of this court.

John A. Perkins, Esquire, of the Boston bar addressed the court as follows:

May it please the court: R. Ammi Cutter, whose active legal career extended to a remarkable sixty-five years (LL. B. 1925 - final retirement in 1990), spent by my calculation at the most twenty-three years in the private practice of law as most of us would probably understand the term. But this statistic gives no indication of the depths of his commitment and contribution in his capacity as a member of the honorable calling of the independent bar. Throughout his career in the law Ammi Cutter played an active and leading role in the institutions of the legal profession and, even apart from his judicial service, in the development of law.

Cutter's years in private practice fall into three periods. A short eighteen months as a new member of the Bar in the firm then known as Goodwin, Procter, Field and Hoar. That was followed by three years as assistant attorney general of Massachusetts. In 1930, he joined the firm then known as Storey, Thorndike, Palmer & Dodge, becoming a partner in 1931. This second period in private practice continued for twelve years, interrupted by a tour of duty as special adviser to the Governor of Puerto Rico in matters of taxation, which resulted in publication of his Report, and interrupted later for, in his own words, "some-five months of nearly complete absence from my office" in organizing the Metropolitan Division of the Greater Boston Community Fund Campaign of 1940. His third period of private practice, following an extraordinary legal service in army uniform in World War II, commenced in 1946 with his return to his firm then known as Palmer, Dodge, Chase & Davis, and continued until his appointment as an Associate Justice of this court in 1956. This ten and one-half years in private practice was, not surprisingly, interrupted for three intervals of service to the United States government: in 1951 to help negotiate an air base agreement with Portugal, in 1954 to investigate some problems of United States military purchasing in Europe, and in 1956 to take major responsibility for presenting the Foreign Aid Program to Congress for the State and Defense Departments and the International Cooperation Administration.

It was during this third period in private practice that I had the privilege of working closely with Ammi, first as an associate and then for six years as a partner in the firm. It was a time when the legal profession was beginning to learn that specialization, if not entirely a virtue, was at least a practical necessity. Ammi, like almost every lawyer, was officially in general practice and in fact was experienced and capable in many areas. But Ammi was ahead of his time. His experience in trying and arguing tax cases as assistant attorney general and his stint as tax adviser to the Governor of Puerto Rico ripened in private practice into his being, even in general practice, an expert in matters of taxation. This continued in his practice after his return to the firm in 1946. I vividly recall an occasion when he was asked by a friend at lunch one day a tax question which I recognized as presenting a difficult issue. I listened with admiration as Ammi gave his friend in simple terms a letter perfect answer to his question, which he concluded by saying: "Now, remember that answer is worth exactly what you paid for it." His friend knew better.

In private practice lawyers recognized in Ammi some of the qualities later to mark his service as a judge. On the Harvard Law Review in law school, in practice he was sharp and incisive in analysis of legal questions and given to careful and thorough scholarship. He was a consummate draftsman. Some probably thought too consummate, but his keen analysis revealed all the possibilities and the drafting task inevitably required that adverse possibilities had to be blocked off not just by inference but in Cutter style by precise and careful drafting.

Ammi practiced law with a compelling sense of personal and professional ethics. I am sure there are many others who have their own windows into this part of the Cutter tradition, I will mention only one of my experiences with it. My role in the firm at the time of at least one of Ammi's separations from the firm for service to the United States government made me the person with whom Ammi initially had to work out the details of the separation. I do not recall what, if any, Federal policies may then have applied, but this was before conflict of interest became a complex body of rules and regulations (and of course, before it became for opponents a part of the arsenal of adversary litigation). Nothing less than a formal written separation and meticulous insulation from financial interest in the firm was thinkable for him.

Ammi's years in private practice foretold another characteristic of his later service as judge -- long hours of work. Eventually, I remember that Mrs. Cutter succeeded in having his secretary, before leaving work, set an alarm clock in the bookcase at a good distance from Ammi's desk to give him the word to get home for dinner. That was still a time when lawyers normally got home for a family dinner hour -- even a late one.

But Ammi's contribution and influence as a member of the independent Bar had a much larger dimension than anything directly involved in his tours of duty in private practice. High among these contributions was his role in the American Law Institute. Elected a member in 1938 at the age of thirty-six, he became a member of the Council of the Institute in 1949. He served in active leadership roles for more than twenty years, including, as already related, President and later Chairman of the Council until assuming emeritus status at the age of eighty-five. He served as Adviser on projects drawing on rather diverse areas of expertise. My impression is that his title of Adviser ex officio on all projects while serving as President and Chairman of the Council does little to convey the background, commitment, and judgment he brought to that role. Ammi was also an ex officio member of the American Law Institute-American Bar Association Committee on Continuing Professional Education from 1976 to 1985 and served as Chairman of the Committee in 1980-1981. The American Law Institute's First Reporter's Chair was named for Ammi Cutter. The work of the American Law Institute was a demanding interest of Ammi Cutter while he was in private practice and continued while he served as a judge. I came on various occasions to know his interest and constructive and effective influence in shaping the work and the products of the Institute.

Ammi brought an unusual background to his service as Adviser ex officio to the American Law Institute Restatement (Third) Foreign Relations Law of the United States, for he in fact had a significant role in an event of seminal impact for the development of international law (including human rights law) that has since occurred in our time. In the Fiftieth Anniversary Report of his Harvard Class of 1922 he notes briefly that his service as staff assistant to the Assistant Secretary of War "involved me in London negotiations (about the then proposed war crimes' trials)." These were the negotiations that resulted in the August, 1945, London Agreement for the Prosecution of the Major War Criminals of the European Axis Powers and the Charter of the International Military Tribunal. Telford Taylor in a 1992 memoir, The Anatomy of the Nuremberg Trials at 75 (Alfred A. Knopf 1992), recounts the history and names Colonel Ammi Cutter among those who "made a major contribution to the project by developing the basic concepts and furnishing the drafts that were the basis of discussion." (Further as to Cutter's role, see 36, 41). A part of Ammi Cutter's war time service this surely was. It was an extraordinary contribution in a career in and out of uniform dedicated to the realization of the rule of law.

Cutter's ventures into affairs of State included more than his war-time experience and more than his three further interruptions of private practice for service to the United States government in 1951, 1954, and 1956, already noted. Another venture is recounted in William Marbury's 1988 memoir, In the Catbird Seat. A friendly get-together at Ammi's summer home in Randolph, New Hampshire, provided the setting at which a major foreign policy effort of the 1950's, the Committee on the Present Danger, was born. North Korea's invasion of South Korea on June 24, 1950, precipitated a new world crisis and fresh alarms over Soviet intentions. See account in David Mcculloch, Truman, at 775-779 (Simon & Schuster 1992). The occasion was a dinner during that summer with Marbury and Tracy Vorhees and their wives. Marbury was Ammi's former chief in the Legal Branch of the Contract Division of the Office of the Under Secretary of War. Some wit, as Ammi liked to recall, referred to Marbury and Cutter as "Arsenic and Old Lace." This story is confirmed in Marbury, in the Catbird Seat, at 158. Vorhees was Under Secretary of the Army at the time of the dinner. The discussion focused on the dangers of a Soviet invasion of an unprotected Europe. In this discussion the Committee on the Present Danger was born. The Committee, which included such prominent persons as former Secretary of War Robert Patterson and former Harvard President James B. Conant, pressed the need for the presence of a substantial body of United States troops in Europe backed by a program of universal service. The first was, of course, achieved and in NATO continues to this day. See Marbury, in the Catbird Seat, at 297-301.

Ammi's involvement in the Bar took a new turn after his retirement from this court in 1972, when the court appointed him special master in the petition by the Massachusetts Bar Association to organize the Bar of Massachusetts as a unified self-governing Bar with official responsibilities by rule of the Court. Cutter was appointed to frame proposed court rules on two possible bases: (a) Part I, so-called, to accomplish certain public functions without an official unified Bar and (b) Part II, to accomplish these public functions with a unified Bar. Cutter found himself sorting through conflicting positions from the Bar on both of the alternative bases and having to guide the development even while maintaining neutrality between the two basic alternatives. Cutter's draft of the Part I rules reflected his recommendation that the Board of Bar Overseers and the Clients' Security Board, each to be involved in carrying out important public functions of the Court, be appointed by the Court and accountable directly to it. See Report, par. 19, sub par. 1, Comment (B), and sub par. 6, Comment (A). In deciding to go forward on the first basis and substantially adopting Cutter's so-called Part I rules, the Court produced fundamental change in the legal profession, change that by now most of the Bar probably accepts as the way it has always been. The rules under which this change was accomplished are in a significant way the principled handiwork of Ammi Cutter.

Ammi was secretary of what he liked to call the great class of 1925 at the Harvard Law School. His devotion to the class and to Harvard Law School reflected a commitment to legal education, and to advancing the careers of promising young lawyers with whom he had occasion to work or to know. Ammi's fine hand is evident in a number of academic and judicial appointments. More public ways in which his commitment to legal education was reflected include service as President of the Harvard Law School Association in 1971 and service, on two occasions, on the Law School Visiting Committee of the Harvard Board of Overseers, serving as chairman of the Committee in 1971-1972.

Ammi's distinguished service and contributions have been recognized: He received the Legion of Merit (with cluster) in 1945 for his war time service; an honorary Doctor of Juridical Science from Suffolk University in 1960; and an honorary Doctor of Laws from Harvard College in 1979.

Especially I wish to note the esteem in which he has been held by his peers in the legal profession. In 1929, at the youthful age of twenty-seven, Ammi was elected a member of the venerable Curtis Club, honored among lawyers. Long its youngest member at the beginning, he was long its senior member at end. In 1980, following Ammi's retirement as President of the American Law Institute, a number of his former law clerks, partners, and friends commissioned a portrait of him to be painted by Gardner Cox for the Harvard Law School. Characteristically, Ammi's consent was somewhat reluctant, protesting that the money would be better spent by adding to a book fund already existing in his name.

In 1984, Cutter was honored by the Boston Bar Association with its Public Service Award. The citation, in which I confess to have had a hand, concluded in words with which I now close:

"Ammi Cutter has brought the finest traditions of the law to a distinguished career as private lawyer, government lawyer and advisor, judge, supporter of legal education and leader in the development of law -- an advocate and exemplar of the highest standards of our profession."

Retired Justice Benjamin Kaplan addressed the court as follows:

Rising to support the motion of the Attorney General, I offer some notes of long association and friendship.

I tell of a day in early April, 1942, when a Major R.A. Cutter, young, buoyant, and obviously of Boston, signed me up for service in the Army. I ventured to remark that a young woman and I were planning to get married later in the month and go off on honeymoon. The Major said that, given the general cussedness of life and the unfeelingness of the Army bureaucrats, I was sure to be called up in the midst of the honeymoon. Thus my introduction to a worldly-wise New Englander. My call-up came just two days after the marriage.

Ammi was the main organizer, deputy chief, then chief of a remarkable office in the Pentagon that came to be widely known simply as the Legal Branch. The first function of the office, according to Ammi, was to try to recognize problems in the field of military procurement before they became crises. Next came the steadier job of coordinating and guiding the legal procurement policies of the several Army services, from Ordnance to Chemical Warfare, not excepting the procurement offices of that separate fiefdom, the Army Air Force; the subjects -- contract standards, pricing, patents, labor relations, property controls, renegotiation, reconversion, and whatever else might turn up. Some of the work became codified in Procurement Regulations, some in sponsored legislation.

To all this wartime jurisprudence Ammi made important substantive contributions, enhanced by his intuitive understanding of how the Army machinery worked or could be made to work. He was notably inventive. I recall an early exploit. The Comptroller General was showing a regrettable lack of plasticity, a morbid attachment to peacetime methods. What to do? Ammi conceived the idea of wheeling up the First War Powers Act and trying to elicit an opinion from the Justice Department interpreting the statute -- this on the basis of an array of carefully calculated questions, Ammi's questions. The scheme succeeded. The man in the Justice Department responsible for a favorable outcome was George Washington, in fact a collateral relative of the President, and Ammi quite naturally inscribed on the formal opinion, "First in war, first in peace, first in the hearts of the Legal Branch." The Comptroller General became reasonably tractable.

Ammi served as manager of the day-to-day activities of the Legal Branch for nearly three years before he went on to more exotic duties with the Assistant Secretary of War. The first chief of Branch, William L. Marbury of Baltimore, was a brilliant, temperamental, sometimes choleric man. The Marbury-Cutter partnership was hailed by a local wit as "Arsenic and Old Lace." Ammi had his own methods of recruiting people, and the results were exceptional. The staff, uniformed and civilian, came from all parts of the country, from all lines of practice, and were individualistic almost to a fault. Ammi understood his associates and welded them into a team. Under daily stress and strain, Ammi remained the user of the unraised voice; only when exasperation became extreme would he invoke the antique swear words, "Hell's bells." In sum, Ammi was a first-class manager, a fact important to an understanding of his lifetime work.

Ammi was loyal without limit to his staff, and they responded in kind. His concern was long term; he looked ahead to the end of the war and set about thinking what would be the best subsequent career for the individual and what could be done to bring it about. In these matters he had a sure confidence in his own judgments. I cite my own case. One day, while improving my draft of a document by his characteristic method of studied understatement, Ammi turned to me and said, without preliminary, "You ought to teach law." This was a surprise, but a couple of years later, there I was, teaching law. Ammi had trained his sinuous powers of persuasion on Dean Griswold and President Conant. I had not been consulted. My story is typical of many others. The host of people whose careers Ammi shaped or assisted were of diverse backgrounds and makeup. And this is the place to observe that Ammi sponsored women in the profession well before it became fashionable to do so.

In 1972, twenty-five years after I was plunged into teaching, I had the honor and great pleasure of succeeding to Ammi's seat on the Supreme Judicial Court, and I pledged then to follow in his footnotes. In 1980, Ammi accepted an invitation to serve on recall in that busy court of intermediate appeal, our Appeals Court, and I joined him there in 1983.

One could see that Ammi took nourishment from his debates and worries and work with younger colleagues; in this way he was sustained in good spirits for a decade until his final retirement in 1990 at the age of eighty-eight.

The manager in Ammi came out in his shrewd advice about the efficient but scrupulous movement of cases on the heavy calendars of the court. Again the manager appeared in a poignant way when -- say in reviewing action by some branch of government -- he was heard to complain, between the lines of the opinion, sometimes with a touch of despondency -- "Don't you see? This or that was the right, the efficient thing to do. Why didn't you see?"

Ammi's grasp of the details of an appeal record was unsparing. He took seriously the maxim ex facto jus oritur, the law springs or ought to spring from the facts. As you read Ammi's opinions, you come upon those famous footnotes that cite all the decisions, relevant, nearly relevant, and sometimes only by the way. Occasionally the footnote seems an expression of a whimsical or wayward interest in the subject. More often it is intended to seal off all the exits -- "to stop up every earth," as Lord Bowen said of the older compendious style of equity pleading (From an essay, Progress in the Administration of Justice During the Victorian Period [1887], reprinted in 1 Select Essays in Anglo-American History 516, 524-525 [1907]). Yet decision is made to rest on a narrow base, so that future developments should not be unduly embarrassed.

There will be more cogent discussion today and in time to come of Ammi's style and merits as a judge, but I like to respond to the question, was he conservative or liberal? A fellow judge has suggested playfully that Ammi might be thought of as nominally a conservative but in truth a closet liberal or progressive. The point is that for a judge of Ammi's caliber the question makes an empty sound -- so various and subtle are the impulses toward decision.

To conclude: Ammi was a fine man of large sympathies and achievements. He was the conscious bearer of an ancestral tradition, but he chose not to be too much trammeled by it; he spread his wings. His unique personality -- old manners tempered to new times -- will abide in the grateful memories of the many whose lives he touched.

Governor William F. Weld addressed the court as follows:

If the Court please, my name is William Weld and I was clerk to Mr. Justice Cutter during the 1970-1971 term. I believe I may safely represent on behalf of Judge Cutter's dozens of clerks that none of us felt worthy to be his clerk -- each of us knew that, in his decades of interviewing, the Judge made one mistake. During my own terrifying job interview with him, I knew I was going to be all right only after I carelessly mentioned that my undergraduate Latin thesis consisted of eighteen pages of text and forty-six pages of footnotes.

I do not know whether Judge Cutter taught each of us more about law or about life.

On the law front, he instructed by example; there was seldom any direct pedagogy. But if you had ears to listen, you could pick up a certain amount from a muttered marginal comment, such as, in a criminal case, "This fellow is going to get cold comfort from the facts as stated by me!"

Judge Cutter never breached the secrecy of the Justices's conference on cases. Nonetheless, I gathered that not every hot new idea that was proposed made it past final cut into the opinion. If the Judge seemed in a particularly good mood -- a mood of one who had successfully excluded error -- I would occasionally ask him, "How'd things go at the conference?" And he would look out the window (he and I never addressed each other directly, only when the speaker was looking out the window), and he would intone: "The King of France, with twice ten thousand men marched up the hill, and back marched down again." That meant that he had gotten the fourth vote.

He was also a man of few words on politics. I asked him a question in 1973: "Should I join the impeachment staff against President Nixon?" Answer: "Only if you're prepared, as a Republican, to go all the way."

Another question, 1978: "Should I run against Frank Bellotti for Attorney General?" Answer: "No, he's done a pretty good job, you'd be a fool."

He was right, of course, in both cases.

Colonel Cutter was a man of no words when teaching about life. It was in the eyes; it was in the eyebrows; it was in the angle of his chin; it was in the hesitation or pause between words, it was in the grace with which he squired Mrs. Cutter -- his bride -- on evening walks around our Cambridge neighborhood in her declining years.

Ammi Cutter was a gentleman, and a gentle man, and I need hardly tell anyone here -- a great man.

Justice Herbert P. Wilkins, speaking for the court, responded as follows:

My colleagues, Governor Weld, Attorney General Harshbarger, Justice Kaplan, Mr. Perkins, members of the bar, members of the Cutter family, and guests.

Ammi Cutter served the Commonwealth and the Supreme Judicial Court with distinction and great ability for sixteen years as an Associate Justice and thereafter in a variety of ways. In 1956, he succeeded my father as an Associate Justice. In 1972, Justice Kaplan succeeded Ammi.

Ammi worked prodigiously, handling some of the most complicated cases that came before the court. During his tenure, cases were not assigned substantially in rotation, as is the case today, but rather in the freely exercised discretion of the Chief Justice. The result was that Ammi was assigned to write for the court in a disproportionate number of difficult cases in fields such as property, taxation, and constitutional law. At a time when there was no Appeals Court and the docket of this court was becoming increasingly crowded, the court and the people of the Commonwealth were fortunate to have Ammi Cutter serving as an Associate Justice. In his final year on the court, Ammi authored seventy-four opinions, forty-four of them full opinions and thirty of them rescript opinions.

Although he was almost thirty years my elder, I knew Ammi Cutter fairly well. He and my father were law partners, and I first encountered Ammi because of that association. I can recall my father, who was not profligate in the distribution of praise, speaking warmly of Ammi's skills as a lawyer. I dealt closely with Ammi for two years as an associate in what is now Palmer & Dodge before Governor Herter appointed him to this court. I recall his poise and tact, as counsel for the insurance companies, at politically charged and volatile public hearings held by the Commissioner of Insurance on the subject of compulsory motor vehicle insurance rates. I also recall the long hours that he worked, his intense focus on detail, and his commitment to high professional standards. These qualities, which I suspect he manifested at an early age, dominated everything he did of which I was aware.

Ammi's judicial opinions are famous for their careful craftsmanship and, as you have heard, often for their considerable footnotes. Other Justices derived some amusement from one oral argument here that focused exclusively on what the court may have meant by language in a particular numbered footnote in a Cutter opinion. It is true, however, that, if one found a Cutter opinion on a point of law, he or she could rely on that opinion, with its exquisite attention to detail, as a full compilation of the law and reasoning bearing on that issue, and probably on a few related ones as well. Yet a Cutter opinion focused on what had to be decided and eschewed pontificating on the likely answers to questions that might some day come before this court but were not yet here.

There is a perception, rightly held, that Ammi demanded more of his law clerks than did most, if not all, other Justices of this court with whom he served. It was not simply a matter of delegation because, while the law clerk was busily engaged, Ammi was working just as hard, or perhaps harder, in his meticulous way. Ammi told the story on himself of the occasion, when near the end of the year of service of one of his early law clerks, he asked the law clerk how the year had gone. "Well," came the reply, a bit hesitantly, "if you had known more, Judge, I would have learned less."

In the same month in 1972 that Ammi resigned from the court, correctly anticipating the people's upcoming vote in favor of mandatory retirement of judges at age seventy, the Supreme Court of the United States appointed him a Special Master to conduct proceedings in an original action that the State of Vermont had brought against the State of New York and the International Paper Company concerning pollution in Lake Champlain. See Vermont v. New York, 408 U.S. 917 (1972). Shortly thereafter a newspaper in the Lake Champlain area published an article announcing the Coast Guard's decision to reactivate one of its vessels. Ammi took particular pleasure in the headline which read: Cutter Recalled from Mothballs. Ammi heard seventy-five days of testimony in that case in 1973. The Supreme Court noted in an opinion that "[t]he Special Master has done a very difficult task well and with distinction; we are grateful for the professional services he has rendered." Vermont v. New York, 417 U.S. 270, 274 (1974). Ammi had interesting tales of his experiences as Special Master. I shall mention one. One day he took a view of a paper mill in New York. Eminent counsel for the paper company, a partner in a large New York law firm, dramatically strode to the outfall pipe of the plant, filled a glass with a brownish liquid flowing from the pipe, and drank with apparent conviction, only to be silently impeached by the obvious trepidation with which the senior partner's young associate attempted to duplicate his boss's performance.

Ammi was strongly loyal and dedicated to institutions and to persons about whom he cared. Justice Kaplan has described Ammi's successful attempt to locate him on the faculty of the Harvard Law School. It is no coincidence that many lawyers who served with Ammi in the Legal Branch in the Pentagon became actively involved in the workings of the American Law Institute. I certainly was a beneficiary in many ways of Ammi's interest in helping the careers of people who worked for him or with him. One of his former law clerks has written that "[t]ime and again for me and, I am sure, for the nearly thirty others who served him similarly, his hand has reached out, unasked and unseen, to advance our careers, open doors to us, and enrich our lives." Ammi was also dedicated to Harvard College; the Harvard Law School; his law school class of 1925; the various clubs to which he belonged; Randolph, New Hampshire, where he spent such summer vacation time as he allowed himself; the American Law Institute; and, of course, his family.

Ammi's endeavors on behalf of the American Law Institute were substantial and productive, but, because the Institute is a national organization, his inner workings for the Institute are not widely known in the Commonwealth. As is true of so many of Ammi's activities, the length as well as the breadth of his involvement with the Institute is impressive. A member of the Institute for more than fifty-five years, he served on its Council for almost forty years, became its president in 1976 at the age of seventy-four, and, in 1980, became chairman of the Council. Ammi worked hard at advancing the interests of the Institute, its finances, its membership, and its projects. He was widely respected for his judgment, integrity, and courteous treatment of others. He brought credit to this court and to the Commonwealth. It was no coincidence that the Institute's First Reporter's Chair was named the R. Ammi Cutter Reporter's Chair. Ammi's worthwhile use of the many years of life with which he was favored is impressive. In his college class's Fiftieth anniversary report, published in 1972, the year that he retired from this court, Ammi expressed the hope that he would have "further opportunities to engage in useful and interesting projects." There were indeed such opportunities, and Ammi seized them. I have already mentioned his postretirement service to the American Law Institute and his work as Special Master in the Lake Champlain pollution case. He performed various tasks for this court, among which was his monumental report as special master and commissioner on the rules to be adopted in connection with the creation in 1974 of the Board of Bar Overseers, the Clients' Security Board, and the process for the annual registration of attorneys. In 1980 he was called back to sit on the Massachusetts Appeals Court where he sat from time to time for ten years, resuming his thorough opinion writing and, by example, teaching his younger colleagues the importance of hard work and attention to detail. While a member of this court, Ammi had had a major role in the drafting of the Appeals Court's enabling statute. Despite his considerable skills and achievements, Ammi maintained a respectful, even reserved, manner in dealing with others. Bravado and self-praise were not among his personal traits. He was soft-spoken, unassuming, and courteous to others with a cautious style that showed perhaps a measure of shyness. His deferential manner toward women had a quality not often found even among his contemporaries. Yet he was supportive of women's rights, sometimes more so than many younger judges. See, e.g., Bell v. Bell, 16 Mass. App. Ct. 188 (1983) (two-to-one decision), S.C., 393 Mass. 20 (1984) (four-to-three decision). One of his granddaughters commented to me once that her grandfather had been most helpful and supportive in her career.

As his wife Ruth became increasingly afflicted with Alzheimer's disease, the task fell to Ammi to deal with the operation of their home on Sparks Street in Cambridge. In time, Ammi became responsible for what was in effect a one-person nursing home. Although it had always seemed to me that Ammi had had little experience in matters domestic, he carried out his task with his usual attention to detail and with sympathy. He told me one day that, although Ruth did not understand what he was reading, and probably did not even know who he was, he read to her because it appeared to make her more restful.

Ammi earned the respect of those who knew him because of his intelligence, scholarship, hard work, courtesy, decency, modesty, integrity, and loyalty to people and to institutions. Typical of Ammi was his restrained comment, written late in life, but well before all his good works were completed, that "occasionally there is a basis for feeling that one's work contributes a little to progress."

The court allows the motion that the Memorial be spread upon the records of the court.