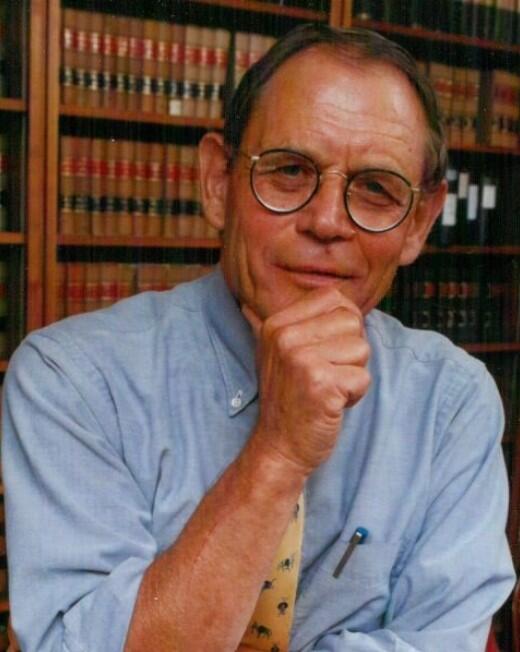

Rudolph Kass

Associate Justice memorial

104 Mass. App. Ct. 1129 (2024)

A special sitting of the Appeals Court was held at Boston on June 26, 2024, at which a Memorial to the late Justice Rudolph Kass was presented.

Present: Chief Justice Green; Justice Vuono; and retired Appeals Court Chief Justice Christopher J. Armstrong.

Chief Justice Green addressed the court as follows:

Good afternoon, and welcome to this special memorial sitting in honor of our former colleague, Justice Rudy Kass. With me on the bench for this sitting are retired Chief Justice Christopher Armstrong and senior Appeals Court Associate Justice Ariane Vuono. Chief Justice Armstrong served with Justice Kass during the entirety of his time on the Appeals Court. On behalf of the panel, and the other Justices of the Appeals Court, current and retired, who of necessity are in the well rather than joining us on the bench, I welcome the members of the Kass family, especially Justice Kass's daughter Liz, and other members of the family who cannot be with us in person today but who are with us on the livestream of these proceedings, including his daughter Sue, granddaughter Claudia, and son Peter. I also want to recognize former Supreme Judicial Court Chief Justice Margaret Marshall, former Supreme Judicial Court Justice Judith Cowin, former Appeals Court Chief Justice Phillip Rapoza, Trial Court Chief Justice Heidi Brieger, and Court of International Trade Justice (and former Appeals Court Justice) Gary Katzmann, who honor us and Justice Kass by their presence here today. Welcome as well to all of the many current and former Justices and staff of the Appeals Court, many of Justice Kass's former law clerks, and quite a number of his friends. It is fitting that we are able to hold this celebration today, two days before what would have been Justice Kass's ninety-fourth birthday.

I now formally begin this proceeding by inviting the Attorney General of the Commonwealth, Andrea Campbell, to present a motion for consideration by the court.

Andrea Joy Campbell, Attorney General, addressed the court as follows:

May it please the court: on behalf of the Attorney General's office and the bar of the Commonwealth, it is my honor and privilege to present a memorial and tribute to the late Rudolph "Rudy" J. Kass, who served as an Associate Justice of this court.

Rudy was born in Magdeburg, Germany, on June 28, 1930, and was the youngest of three sons born to Heinrich Kass and Lily Minna Cohen. During his youth, the Kass family fled Germany's Nazi rule, first moving to Tel Aviv in 1935, then to Long Island, New York, in 1937.

After completing his undergraduate studies in 1952 at Harvard College, where he was managing editor of The Crimson, the student newspaper, Rudolph Kass went to Berlin to photograph and write freelance pieces for United States publications. Once while photographing Communist-controlled East Berlin, Rudy was arrested at gunpoint and thankfully had his release secured by United States High Commissioner James Conant. His later descriptions of the experience, in fact, included some commentary by the High Commissioner (who had been president of Harvard while Justice Kass was a student there): "Kass, you are a very ill-advised young man."

Following some time abroad, Rudy returned to the United States, where he met and, in 1953, married his wife, Helen. The couple was introduced while working at the same Connecticut resort. During their marriage, Mrs. Kass worked in college admissions to support herself and her husband during his law school studies.

Following his graduation from Harvard Law School in 1956, Rudolph Kass joined and later became a partner at Brown Rudnick Freed & Gesmer (now Brown Rudnick LLP), specializing in real estate with a concentration in urban affairs. In 1965, he served as counsel to the special legislative committee that drafted a statute creating the Massachusetts Housing Finance Agency, now known as MassHousing.

In 1978, Governor Michael Dukakis appointed Justice Kass to the Appeals Court, as part of the court's first expansion. He quickly acclimated to appellate work and earned a reputation for keen attention to detail and formidable legal reasoning. During his twenty-one year tenure, Justice Kass wrote 1,600 opinions, approximately 200 of which were single justice memoranda and orders. As someone who had originally imagined a career in journalism, Justice Kass took great pleasure in authoring opinions, employing nuance, humor, and wit where perhaps unexpected, but never unwelcomed.

Justice Kass reached mandatory retirement age in June of 2000 but remained a recall judge until 2003. He lectured and wrote extensively on subjects related to real estate and was the editor and author of several chapters in Legal Chowder: Lawyering and Judging in Massachusetts. He was a mediator and arbitrator with The Mediation Group and was an adjunct professor at Boston College Law School, where he taught real estate. Justice Kass served as director of both Jewish Community Housing for the Elderly and the Legal Advocacy & Resource Center and was a trustee of Brigham and Women's Hospital and served on its ethics committee.

Justice Kass was a cherished friend and colleague within the court's walls and at any institution fortunate enough to welcome his contributions. He is celebrated for his openness, curiosity, humor, and generosity and remembered for riding his bike to and from work, his devotion to social engagement, and his iconic judicial opinions.

Rudolph Kass celebrated sixty-two years of marriage before the passing of Mrs. Helen Kahn Kass in 2016. They were the proud parents of Liz, Sue, and Peter, and grandparents of Joanna, Claudia, and Maria. On June 4, 2021, at the age of ninety, Justice Kass passed away peacefully at his home, with his family nearby.

Mr. Chief Justice, it is an honor for me to be here today to pay tribute to Justice Kass, a truly outstanding judge whose commitment to public service is an example to the entire legal profession. On behalf of the bar of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, I respectfully move that this Memorial be spread upon the records of the Appeals Court.

Retired Chief Justice Christopher J. Armstrong addressed the court as follows:

To my colleagues on the bench and off the bench, in the audience to the judges from other courts, particularly the Supreme Judicial Court -- Chief Justice Marshall, Justice Botsford, Justice Cowin -- I'm honored to be asked to speak here today and to offer some thoughts about my time with Judge Kass.

Justice Kass first came to the Appeals Court when he was appointed in 1978. The Appeals Court, at that time, had six judges. I was one of the original judges on the court and unfortunately am the only one still around to talk about it. So, without fear of being corrected, I say that I remember when, in 1978 -- this is six years after we started -- we had already fallen so far behind in our work that the Legislature authorized four additional judges to bring the complement of judges to ten. The four judges that were appointed that day in 1978 by Governor Michael Dukakis were Charlotte Perretta, Raya Dreben, Rudy Kass, and John Greaney -- a day's work that should make any Governor feel very proud indeed. These were commendably strong appointments, and the Appeals Court leaned on them for the remainder of their service on the court, which was for a very long time.

It became evident from the start that, in Rudy, the Appeals Court had picked up one of the most effortless writers of legal opinions not only in our court, but in Massachusetts and in the nation. Rudy's opinions were extraordinary. We have never had such a facile wordsmith putting sentences together. There are many instances of quotes from his opinions that appeared in statements at the ceremony where he was interred. Chief Justice Green spoke at that interment, and Bill Poorvu, who was an old, old friend of the Kasses. Later at the memorial service there were talks by the Kass grandchildren, and many of them quoted Rudy's opinions, which are a store of uniquely wonderful phraseology.

An example not mentioned at the interment, one that I particularly liked, was from his opinion in Levings v. Forbes & Wallace, Inc.1 This was about three years after Rudy came to the court. He was called on to define what it took to constitute a G. L. c. 93A violation beyond breach of contract, and he said that at least it had to be conduct "that would raise an eyebrow of someone inured to the rough and tumble of the world of commerce."2 I love that idea, "that would raise an eyebrow of . . . ." Who but Rudy would come up with that phraseology? There are countless others; frequently mentioned is a case where Rudy came to grips with what constitutes a delicatessen in Massachusetts law -- which is one of the best opinions I've ever seen!3 One picked up an opinion by Judge Kass with great anticipation and joy because unlike the more pedestrian output of his colleagues, like myself, he had a way of making the reading thoroughly enjoyable.

I want to talk not about Rudy's writings because a lot has been written about those and they are all there for people to see, but rather about the role that Rudy played in building what I think of as the enlarged Appeals Court. I begin with the story of Judge Joseph Warner, whom the Governor appointed Chief Justice of the Appeals Court after the elevation of our second Chief Justice, John Greaney, to the Supreme Judicial Court. There had been four candidates from within this court for the Chief's position. I was one, Rudy was another, Charlotte Perretta was another, and Joe Warner was the fourth. The process involved the judicial nominating commission (this is a short lesson in how judges get appointed -- many of you know because many of you here are judges and have had to go through the process). Since the time of Governor Frank Sargent and Governor Michael Dukakis, Governors from whichever party have appointed large judicial nominating commissions. In the earlier days, at least, it would often consist of twenty or twenty-five prominent lawyers, and there was a very elaborate process of long applications, comprehensive background checks, and interviews, after which the nominating commission would recommend three names to the Governor as the best qualified for the vacant position. The Governor could send the list back to them, but more often, the Governor would pick from the nominating commission's list of three.

To fill the Greaney vacancy, the judicial nominating commission met one evening and had the four of us in-court candidates for Chief Justice all in the waiting room at the same time. We went in one after another to be interviewed by the nominating commission. The nominating commission recommended three of the four in-court candidates to the Governor, who nominated Joe Warner for the Chief position. Unfortunately, quite early in his tenure as Chief, Joe Warner suffered a debilitating stroke marked by long periods of absence from the court. I, being part of the original court, was at that time the senior Associate Justice and therefore had to serve as Acting Chief when Chief Justice Warner was not there -- the same position that Judge Vuono is in now, senior Associate Justice. Luckily, she hasn't had much work to do in that position because she's had a very healthy and capable Chief present throughout, but it was otherwise with Judge Warner -- who before the stroke was a wonderful lawyer, and one of the strongest appointments to our court. It was massively unfortunate that the stroke had inflicted terrible damage and he was out so much, but the result was that for many years, I ended up serving periodically as Acting Chief Justice during extended absences.

When Judge Warner retired from the court in February of the year 2000, having become too ill realistically to have any prospect of returning to the job, the process of the judicial nominating commission never got put in motion. My colleagues, at the time, under the leadership of Judge Kass (I was not part of it; I never knew they were meeting) met and decided that, having been Acting Chief for so long, I should be the next Chief and signed a letter to that effect to then-Governor Paul Cellucci. Rudy brought the letter over to his friend Len Lewin (who was Paul Cellucci's chief legal counsel), and they decided that the appropriate thing to do when it was signed by all other judges on the Appeals Court was to finesse the nominating commission procedure. They simply didn't list the position. I remember getting word of my appointment in a very abbreviated time after Judge Warner's resignation. Thus, I came to the job in a way that got me off to a start that no other Chief Justice could have had the benefit of -- the unanimous support of all of my colleagues asking that I be their Chief. This was Justice Kass's doing.

The Appeals Court at that time was, as it perennially was, desperately far behind in its work. There were intrinsic faults with our statute that almost guaranteed that so long as our caseload was rising, as it had been since our creation in 1972, we would always be behind and that we would always have too few judges. I had come from working under Superior Court Chief Justice G. Joseph Tauro, who later became Chief Justice of the Supreme Judicial Court. The Superior Court was desperately short of judges, and he argued convincingly that there was no viable solution to court delay other than to have enough judges to do the work. More and more it became evident to me that that was the case. When I went before the judges, after I had been told of my appointment, we all agreed that we should ask for three more judges for the Appeals Court. As we were fourteen then, that would get us up to seventeen.

It was Rudy who got the process started. Judge Warner had resigned February 1 of 2000. We did not want to wait until the next Legislature in 2001 to get the bill considered by a Legislature that could enlarge the court. The only way to advance the process was through the Governor, by means of a special message, so we went, Rudy and myself, to see Rudy's friend Len Lewin, Governor Cellucci's chief legal counsel, and he, although entirely favorable to the special message proposal, suggested that it would be a mistake to ask for only three judges and that we should leave ourselves negotiating room by asking for five. Rudy and I came back and reported to our judges that, through the Governor, we would be asking for five judges now instead of three. The judges were generally pleased, although some worried about where the new judges would sit and other minutiae.

The Governor sent in his special message asking for five new judges for the court. During the pendency in the Legislature, I had a meeting with the Speaker of the House of Representatives, Thomas Finneran, who had been the Chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee, and he asked me how soon we could get caught up if we had five additional judges. Luckily, thanks to Alex McNeil, the executive secretary of our court, I had facts and figures up to my armpits and was able to calculate very quickly how many additional judges would be needed to staff enough panels to get caught up within three years, which we agreed was a reasonable and realistic time to achieve a one-year period from entry of an appeal in the court to a final decision in that appeal. In this way we arrived at a staggering figure of eleven additional judges to reach and maintain the goal of current operation. The figures made sense; they were our own calculations. It would take three years to get rid of the backlog. So I made the promise that if we got eleven judges, we'd get caught up in the sense of meeting our proclaimed target for being current, that is, hearing all of our cases that had been briefed by the end of February before we recessed for the summer. The Speaker was convinced, and the Governor's bill was reported out of the House amended accordingly.

Now it was time to sell that package. It was obviously an extraordinary jump in judges for the Appeals Court. We needed newspaper support. No lawyer knew the newspaper landscape better than Rudy, who had worked in and for newspapers, had been around newspapers his whole life ever since he graduated from Harvard as editor-in-chief of the Crimson. He got us appointments with the editorial boards of the various newspapers, all of whom knew Rudy well and were very receptive. A proposal by Rudy was presumptively sound, and the upshot was that all the major papers editorialized for the expansion. Next, we went to the bar associations, who leapt into action. The Boston Bar Association, under the energetic leadership that year of Thomas Dwyer, produced a lengthy, detailed report talking about the problem of the Appeals Court and how many additional judges it would take the court to get caught up, and not surprisingly it came out to eleven. The Massachusetts Bar Association endorsed the same position as did the major newspapers. All of this was part of Rudy's work. His leadership was crucial in that period between the resignation of Judge Warner and the time when we worked together to expand the court.

I credit Judge Kass as a major architect of the expansion of the court to its present size. The expansion has, in fact, been central to fixing the long-standing problem of the Appeals Court delay. The Appeals Court today has no backlog, astonishingly to one who spent most of his thirty-six years on the bench wallowing in backlog. I owe much of the credit to Judge Rudy Kass. His leadership in every respect in the court was exemplary. He was the Chief's strong right arm, always constructive, always sound, always persuasive. Rudy was a simply extraordinary person. The fact that he was so gifted verbally was additional frosting on the cake. He happened to be the best writer of our generation, but he brought many other talents to the court.

Obviously, I have to stop at some point. Way back in my past when Adlai Stevenson was running for President, he ended a lengthy talk by saying, "I feel like a little girl who was asked if she knew how to spell banana, and she said, 'I know how to spell banana, but I don't know when to stop.'" I think having delivered these thoughts about my memories of Rudy, I should turn the podium back to Chief Justice Green.

Retired Appeals Court Justice Raya S. Dreben submitted the following remarks:

Rudy was a brilliant judge and a magnificent writer. A judge's judge. But when I think of Rudy, my first thought of him is that of a dear friend, a warm and fuzzy one, a man who loved people and who in turn was beloved by many. I remember when we first were appointed, and I walked with him down Court Street or Devonshire Street, almost every person we passed said, "Hello Rudy." I was absolutely astounded at the number of people who knew Rudy.

Rudy and I were midnight judges, but he was even more midnight than I was. His charming wife Helen couldn't even come to his swearing in. Afterward she became an integral part of Rudy's presence on the court, for she, as did Liz Armstrong with Chris, often accompanied him to court functions and was so much a part of the court that Helen was dubbed our eleventh judge.

Rudy was not only a professional colleague but, with Helen, was socially friendly with many of the judges not only on our court but also on the Supreme Judicial Court and in the trial courts. He sailed with Judge Hale and went camping or hiking with others. I remember fondly many dinners my husband and I had with Rudy and Helen both at their house and at ours.

Rudy also was fun to sit with on the bench. I believe all of us loved to sit with him. His command of words and humor was a delight. Those of us who were fortunate enough to know him and to share so many experiences with him miss him sorely but are most grateful to have had his friendship.

Judi S. Greenberg, Esquire, addressed the court as follows:

May it please the court: my name is Judi Greenberg, and I had the privilege of serving as a law clerk to Justice Rudolph Kass. I am honored to speak today. I thank the Kass family and the court for inviting me to share reflections on behalf of his law clerks, with whom I had the pleasure of connecting ahead of these remarks.

To have the great fortune to serve as a law clerk to, and work together with, Judge Kass is to receive a gift that lasts a lifetime. He was our teacher, mentor, confidant, and life-long friend. Judge Kass engaged with passion in work he loved, a lesson all on its own. It was inspiring to see his sharp mind and quick wit, tremendous energy, discipline, and dedication applied to his cases, all the while having fun. A clerkship year provided an incredible lens through which to watch and learn from him about the law, precise and concise legal writing, sound reasoning, work ethic, and being a good colleague. Perhaps most important, by example, he modeled with dignity how to lead a meaningful and joyous life, punctuated throughout with good humor.

Judge Kass had a perpetual curiosity and desire to learn, and he immersed himself in each case. No fact or question was set aside until it was wrestled to the ground to his satisfaction. Former law clerk Kathy Rogers recalled working on a real estate case, which rested on whether a response by the defendant to a sealed bid offered by the plaintiff to purchase, in Judge Kass's words, a "choice 40-acre property," created an enforceable contract.4 The court record included this statement by the defendant to the plaintiff: "Congratulations, you've bought the farm."5

One wintry day, Justice Kass came to Kathy's desk and announced: "Get your coat and hat, we are going to do some field research." They headed to the Boston Athenaeum to determine the origin of the phrase "bought the farm." Believing it was aviation jargon, he needed to know when and where the phrase originated, whether it had multiple meanings, and any other relevant facts.

Leaving no stone unturned after several hours at the Athenaeum, Judge Kass wrote an opinion affirming the ruling for the plaintiff, and included this footnote:

"We do not know if irony was intended. The phrase 'bought the farm,' is slang for death, usually accidental. Roots of the expression are variously traced to military and early aviation usage. See Morris, Morris Dictionary of Word & Phrase Origins 80 (1977); Chapman, New Dictionary of American Slang 57 (1986)."6

In the court room, his demeanor was always kind and respectful. He was mindful of the high stakes for the individuals whose lives would be altered by a judicial opinion. Interestingly, former law clerk Marjorie Butler knows Clarissa Allen, the owner of the farm on Martha's Vineyard on which Sebastian, the tobacco-chewing sheep, was brought to life by Judge Kass in Allen v. Batchelder.7 The decision allowed Ms. Allen to keep her family farm acquired more than 200 years before, and secured her livelihood and a home for herself, Sebastian, and their descendants. Marjorie shared that Ms. Allen still expresses her gratitude to Judge Kass for his understanding of the facts and his judicial opinion. As do we all.

Judge Kass likewise was dedicated to his clerks' learning. A few weeks into my clerkship, Judge Kass told me he would be serving as single justice in the coming month, and that a better learning experience would be to work with Judge Benjamin Kaplan, a recall judge and retired Supreme Judicial Court Justice, who was also Judge Kass's teacher and mentor. I knew three things about Judge Kaplan: that Judge Kass revered him, that he seemed very intimidating, and that, after a few short weeks of clerking, he told his current clerk (who would become and remain a close friend of mine) that she had made the wrong choice of profession. I was terrified. I worked with him on a criminal case with tragic and awful facts. Between the case itself and my fear of Judge Kaplan, I had many sleepless nights. I spent those waking hours dissecting Judge Kaplan's opinions for any clues I could glean about his legal analysis, how it was structured, his use of language, even punctuation, and I wrote and rewrote my memo. Likely due to some divine intervention, Judge Kaplan seemed pleased with my work. Judge Kass was right; I did learn a lot. Having survived, however, I was eager to return to my work with him. My first happy day back, we were discussing a case about which we held differing views. As I was thinking about how lucky I was to freely exchange ideas with him, in walks Judge Kaplan. Without skipping a beat, Judge Kass said, "Why don't we ask Judge Kaplan for his opinion," and he explained the case. With a familiar pit back in my stomach, I thought, "How can this possibly turn out okay? Either Judge Kaplan finds my position flawed and/or nonsense and I will be embarrassed in front of two judges or, much less likely, he agrees with my position." But I didn't yet know Judge Kass well enough to be sure what that would mean. Against all odds, Judge Kaplan favored my argument. I looked over at Judge Kass, who had a wide smile on his face. He later told me he was proud and that I should be, too.

Each conversation with Judge Kass held something new and interesting. When discussing a case, former clerk Paul Rozelle recounted an early conversation familiar to many of us. Encouraging us to share what we were thinking because he was genuinely curious, Judge Kass said, "I already know what I think; I want to know what you think." Conversations often turned to books, our interests, current events, and our families. He spoke proudly about his family. With love and deep admiration for his wife, Helen, he told me on more than one occasion, "Helen would have made a far better judge than I." He took pride in their children, Liz, Peter, and Sue, in how they were navigating their own paths in life. Being his clerk was to witness his full participation in, and curiosity about, the world and to learn from it. He engaged in his life at full tilt.

Outside of the court house, Judge Kass went on adventures with his clerks, such as sailing and skiing. As reported by Paul, on one ski trip, Judge Kass gleefully yodeled his way schussing down the slopes. He and Helen celebrated our life events. He officiated at a few of our weddings, and they attended others, dancing together with grace and exuberance, as I can personally attest. They supported us during challenging times, through loss and illness. As a group, his law clerks were delighted to be able to celebrate his eightieth birthday at their home. Throughout his life, he was always tickled to hear from a former clerk.

Inhabiting his values, he embraced each moment he was given by living fully, intentionally, graciously, and with integrity and vigor, as both a stellar judge and as the remarkable mensch that he was.

Accordingly, Judge Kass's law clerks are joined by Sebastian, the tobacco-chewing sheep,8 sixteen barking dogs,9 a wolf in a local zoo prone to pushing "enough of his snout through his pen to bite,"10 and the owner of a deli,11 and we collectively ask that this court allow the motion of the Attorney General.

Chief Justice Green responded for the court as follows:

As many of you know, I offered reflections on Justice Kass's legacy in several settings at the time of his passing three years ago, so if some of what I am about to say sounds familiar to some of you, that is the reason.

I first met Rudy Kass, and Helen, in the fall of 1997, as we took our seats in a shuttle bus from the airport in Great Falls, Montana, to the hotel where our little group would stay before launching a canoe trip down the upper Missouri River, retracing a portion of the Lewis and Clark journey described in Steven Ambrose's book Undaunted Courage. It was one in a series of back country excursions organized by Superior Court Judge Paul Chernoff, and just four months into my time as a trial judge in the Massachusetts Land Court, I was most fortunate to be included among four other veteran Superior Court judges, and Rudy. I was as nervous as a teenager at a high school dance, which is the only explanation I can offer for my ill-advised choice to initiate small talk with a comment praising an opinion by Supreme Judicial Court Justice Charles Fried in the case of Goulding v. Cook.12 I was unaware at that time that Rudy had authored the Appeals Court opinion in the same case, and that Justice Fried's soaring rhetoric reversed the conclusion Rudy and the Appeals Court had expressed. It is a testament to Rudy's good nature and graciousness that, despite that inauspicious beginning, he took me under his wing and mentored me throughout my judicial career, and became a beloved friend. It is also a testament to Rudy's love of the outdoors -- and his sense of adventure -- that he was known throughout his tenure on the Appeals Court for riding his bicycle to work; in fact, his bicycle was his preferred mode of transportation around Boston, despite numerous harrowing experiences, until his children finally persuaded him to set it aside when he was in his mid-eighties.

My relationship with Rudy was built principally around our work as judges. We bonded over a shared love of what we both called "dirt law." Real estate is always about location, and each location has its own story. With his background as a newsman, Rudy was particularly expert at seeing and telling those stories, and doing so in ways that spoke to lawyers and lay readers alike, breaking down subtle and complex legal concepts into terms that anyone could understand. But he also invariably added a level of color often absent from dry appellate case law. I have my own list of favorites among his opinions, but there are many other contenders.

You heard Attorney Greenberg talk about Allen v. Batchelder,13 the case involving the Allen family farm on Martha's Vineyard. That opinion explained the concept of ouster -- the doctrine by which one fractional owner of property may extinguish the interest of another -- a very dry concept, but he started the opinion from an intriguing perspective: anthropomorphized livestock. He opened the opinion with the following unforgettable line: "Sebastian, the tobacco-chewing sheep, would have been disconcerted by this appeal." He went on to explain how Sebastian symbolized the open and obvious -- and long-standing -- occupation the Allen family had made of the farm they claimed now to own, free of any fractional interest held by the distant heirs of a former cotenant.

In the field of real estate law in particular, Rudy was legendary. On the sometimes murky question of when parties became bound during their progression from an offer to purchase to full agreement, Rudy offered a simple and pragmatic, but also evocative, framework for the preliminary stages of negotiation in Goren v. Royal Investments:14 "There is commercial utility," he observed, in "allowing persons to hug before they marry."15

On a question of interpretation of a noncompetition covenant in a lease, in Kobayashi v. Orion Ventures,16 the case to which Chief Justice Armstrong alluded earlier, he discussed the essential nature of a delicatessen, including a footnote recounting the classic comment by the proprietor of the Carnegie Deli in New York following a robbery: "Idiots! They took the money and left the pastrami."17 By the way, in case that reference intrigues you to look at the opinion itself, I commend to you as well footnote 9, which illustrates the circular logic of an argument advanced by one of the parties by reference to Gilbert and Sullivan.18

Rudy's style was sufficiently unique that his hand was obvious even in a brief rescript opinion, issued without authoring attribution. While I was still in the Land Court, when I opened the daily advance sheets in the morning in April of 2000 and saw the opening line of Commonwealth v. Buzzell,19 I knew immediately who had written it. The case involved a challenge in a criminal case to the sufficiency of the evidence supporting conviction under a statute that required the removal of dogs whose barking caused a nuisance. The defendant argued that there was no proof that the dogs who provoked the complaint were the same as those who remained on the property on the date he was arrested for failing to remove them. Rudy's opinion opens as follows: "Sometimes a dog's bark can be as bad as its bite."20 Continuing, he explains that "[t]he answer to the defendant's 'at least one identical dog' argument is that [the statute] recognizes the fungibility of barking dogs. The mischief to be corrected is excessive barking and whether the source of the barking on the premises is Fang or Fido is not of the essence."21 He was surely one of the most colorful and visible members of the Appeals Court in its history, and remains one of those most often cited.

Rudy also was notable for his continuing engagement in the wider community. While the Code of Judicial Conduct does not prohibit judges from engaging in their communities, the limitations often cumulatively, over time -- particularly for those in long service -- induce many judges to follow the path of least resistance and withdraw, at least somewhat. But not Rudy -- he remained active in more social clubs than I knew to exist, and he contributed generously on a wide variety of charitable and nonprofit boards. His visibility in our wider community was not merely a product of the prominence and color of his judicial writings.

As I came to know Rudy, I also came to know Helen. Theirs was an inspiring and continuing romance. It was evident in even the most casual observation of the two of them together -- and they were almost always together -- how intertwined they were. They demonstrated a comfortable and gentle intimacy, based on mutual respect, that was a model of what a marriage can be.

When I think of the attributes that most describe Rudy, three come to mind: optimism, curiosity, and adventurousness. Combined, the three capture his openness -- to new ideas, to new ways of doing things, and to new friends. He is an iconic figure in the Massachusetts judiciary, but his legacy extends beyond his work to the personal connection he made with so many. As a giant in the judiciary, and as a friend, he is greatly missed.

Attorney General Campbell, on behalf of myself and all the Justices of the Appeals Court, it is my great honor and pleasure to allow your motion, and to direct that these proceedings be spread upon the records of the court.

Footnotes

- Levings v. Forbes & Wallace, Inc., 8 Mass. App. Ct. 498 (1979).

- Id. at 504.

- Kobayashi v. Orion Ventures, Inc., 42 Mass. App. Ct. 492 (1997).

- Hunt v. Rice, 25 Mass. App. Ct. 622 (1988).

- Id. at 625.

- Id. at 625 n.3.

- Allen v. Batchelder, 17 Mass. App. Ct. 453 (1984).

- Allen, 17 Mass. App. Ct. at 453.

- Commonwealth v. Buzzell, 49 Mass. App. Ct. 902, 902 (2000).

- Alfonso v. Lowney, 11 Mass. App. Ct. 338, 338 (1981).

- Kobayashi, 42 Mass. App. Ct. 492.

- Goulding v. Cook, 422 Mass. 276 (1996).

- Allen, 17 Mass. App. Ct. 453.

- Goren v. Royal Invs. Inc., 25 Mass. App. Ct. 137 (1987).

- Id. at 142.

- Kobayashi, 42 Mass. App. Ct. 492.

- Id. at 493 n.3.

- Id. at 500 n.9.

- Buzzell, 49 Mass. App. Ct. 902.

- Id. at 902.

- Id.