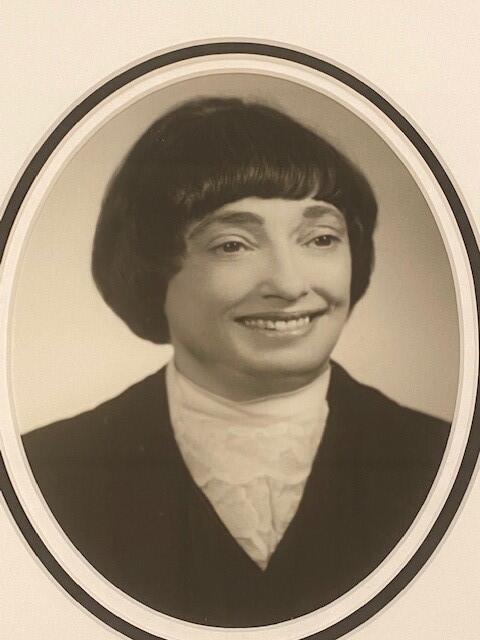

Ruth I. Abrams

Associate Justice memorial

486 Mass. 1117 (2020)

A special virtual sitting of the Supreme Judicial Court was held on November 12, 2020, originating in Boston, at which a Memorial to the late Justice Ruth I. Abrams was presented.

Present: Justices Lenk, Gaziano, Lowy, Budd, Cypher, and Kafker; and retired Supreme Judicial Court Chief Justice Herbert P. Wilkins.

Justice Lenk addressed the court as follows:

Good afternoon. On behalf of the Justices of the Supreme Judicial Court, I am pleased to welcome you to this Memorial for the Honorable Ruth I. Abrams.

We are, of course, still reeling from the shock of losing Chief Justice Gants, who was scheduled to welcome you. Even during the pandemic, Chief Justice Gants was intent on planning this special tribute to Justice Ruth Abrams. He was keenly aware of the important and historic role she played on the court, in the bar, and in the Commonwealth.

As she was for so many women, Justice Abrams was also a role model for me as I began my legal career. I am grateful that we are here together this afternoon to remember Justice Ruth Abrams and to honor her historic contributions.

In non-pandemic times, this virtual memorial sitting would have been held in the Seven Justice Courtroom of the John Adams Courthouse, but these are pandemic times. Notwithstanding the virtual nature of our coming together, the Justices are delighted to be here with you.

We especially recognize and welcome several people who are viewing today's Memorial virtually. We welcome Justice Abrams's brother, George Abrams; and Justice Abrams's sister, Susan Medalie, and her husband Richard. We also welcome her nieces Sarah and Rebecca, and Justice Abrams's nephews Samuel and Daniel, as well as their respective spouses. We welcome Justice Abrams's many cousins, their children, all members of her family, and her close friends. In this regard, we welcome two devoted friends, Mary Holbeck and former Appeals Court Justice Elizabeth Porada.

And, of course, we welcome Justice Abrams's former secretary, Joyce Hurley, a dear friend to Justice Abrams for many, many years, who has been instrumental in planning this memorial sitting.

I welcome Justice Abrams's former law clerks and many of our court staff past and present. I am also very pleased to welcome back to the court former Chief Justice Herbert P. Wilkins, as well as many members of the Massachusetts and United States judiciary. Thank you all for participating.

The court now recognizes Attorney General Maura Healey.

Maura Healey, Attorney General, addressed the court as follows:

Good afternoon, and may it please the court: Maura Healey, Attorney General, on behalf of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts.

As the Attorney General of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, it is my honor to present, on behalf of the Commonwealth, a memorial and tribute to the late Justice Ruth Abrams.

Justice Lenk, Justice Gaziano, Justice Lowy, Justice Budd, Justice Cypher, Justice Kafker, it is truly an honor to appear before you today as we recognize and celebrate the distinguished legal career of your former colleague, Justice Ruth Ida Abrams.

I know members of Justice Abrams's family are here with us today, including her brother George and her sister Susan, her nieces and nephews Sarah, Rebecca, Samuel, and Daniel, their spouses, and her grand nieces and nephews.

It is a pleasure to be here with so many well-respected members of our legal community. We have all come together to pay tribute to Justice Abrams, a dedicated jurist and a pioneer for women in the legal profession.

Justice Abrams was born in December of 1930. She was raised in Newton, Massachusetts, and graduated from Radcliffe College in 1953, where she studied government and foreign relations.

In the fall of 1953, Justice Abrams was just one of nineteen women who were starting at Harvard Law School, only the fourth class of women to do so. After graduation, she worked for her father's law practice.

Then, a former professor recruited her to become an assistant district attorney at the Middlesex district attorney's office.

In 1968, her former classmate -- and one of my predecessors -- Bob Quinn, approached her about joining the criminal division of the Attorney General's office to work as the chief of appeals.

In 1971, Justice Hennessey offered her a position as staff counsel to the Supreme Judicial Court. For a year she worked as staff counsel to the Supreme Judicial Court, before receiving a call from Governor Sargent.

In 1972, she was offered a judgeship in the Superior Court, only the second woman nominated to that bench. It was then, in 1977, that Governor Dukakis nominated her for the Supreme Judicial Court, the very first woman in Massachusetts history to sit on that bench. In her twenty-three years of service, Justice Abrams wrote over 500 opinions.

Her groundbreaking role made her an inspiration and role model for women in the legal profession.

In the words of Chief Justice Margaret H. Marshall, "She had a profound belief that the foundation of our society is equal treatment under the law, and she spent her life putting that into practice. But mostly, her impact was in influencing the number of women and minorities who were appointed to the courts. She single-handedly changed the face of the Massachusetts judiciary."

Justice Abrams occupies a special place in the history of this court. On behalf of the Commonwealth, I respectfully move that this memorial be spread on the records of the Supreme Judicial Court. Thank you.

Edward Notis-McConarty, Esquire, addressed the court as follows:

May it please the court.

Good afternoon Justice Lenk, Associate Justices of the Supreme Judicial Court, Attorney General Healey, members of the Abrams family, and fellow presenters Chief Justice Wilkins and Mary Ryan.

I am honored to speak on behalf of the bar about the extraordinary career of Justice Ruth Abrams. I bring to these remarks the perspective of the bar, as well as a personal perspective, as I served as Justice Abrams's second law clerk in 1978 and maintained a professional and personal friendship with her for the rest of her life. In connection with doing estate and personal planning for Judge Abrams, I have gotten to know her family, much to my delight.

As just highlighted by the Attorney General, Maura Healey, Judge Abrams broke an impressive series of barriers. Never one to call attention to herself, Ruth Abrams was nevertheless a shining inspiration to the bar, and particularly to the increasing numbers of female lawyers. She exemplified the talents and unique contributions which women brought to the bar and especially to public service.

Justice Abrams's roots ran deep and are the key to understanding her personal and professional gifts. She was born in 1930 into a strong Jewish family in Newton, Massachusetts. Her father's solo legal practice focused on solving clients' problems of all types. She walked into first grade in the Newton public schools hand-in-hand with her brother George, who himself has had an impressive career in the law. Together, Ruth, George, and their sister Susan, also to become a distinguished lawyer, spent summers in Hull enjoying close family and the seashore. Judge Abrams grew up in a family which valued close family connections and hard work. Her sister Susan has said that "bad grades were not allowed in our house." Their father's service to his clients was a clear model to the three children, as they worked in his law office and accompanied him to court. They learned by his example that the law is a service profession, involving practical solutions to clients' problems and contributing to the community.

Judge Abrams went on to break barriers at Radcliffe College. At Harvard Law School, she graduated in 1956, one of thirteen women among 560 men. Judge Abrams was a member of one of the earliest classes to which women were admitted to Harvard Law School. It was not an environment hospitable to women. Professors designated one class per month as "ladies day" where female students were put on the hot seat as a form of entertainment. Socially isolated from study groups and other informal networking opportunities available to male students, the women were invited to awkward "ladies night" dinners with the dean, dinners which Justice Abrams remembered as uncomfortable for all. Justice (then "just Ruthie") Abrams found that there were no women's bathrooms available. As throughout her life and her career, Justice Abrams rose above the barriers, and succeeded.

Coming from a very traditional, close family, Judge Abrams built on that foundation and, with impressive intelligence and hard work, displayed talents which could not be denied, even by those previously unwilling or unable to see the contributions women could make.

As a Justice on the Supreme Judicial Court, Ruth Abrams continued to open eyes and change perceptions. She also changed the law, particularly with respect to women and families.

In a landmark decision, written in her first year on the Supreme Judicial Court,1 Judge Abrams ruled that the Massachusetts Electric Company's disability policy constituted unlawful discrimination on the basis of sex. The disability policy excluded coverage for work time missed for pregnancy-related conditions, including hospitalization of several women due to miscarriages. The policy covered disabilities unique to men, but not medical complications of pregnancy. The company argued that discrimination on the basis of pregnancy was not the same as discrimination on the basis of sex. I can picture the twinkle in her eye when she wrote, tongue in cheek:

"Pregnancy is a condition unique to women, and the ability to become pregnant is a primary characteristic of the female sex. Thus any classification which relies on pregnancy is a distinction based on sex."

Judge Abrams's male colleagues joined her unanimously in this decision.

In Gottsegen v. Gottsegen,2 a 1986 opinion, Judge Abrams again wrote for a unanimous court in a decision holding that the trial judge in a divorce case could not enter a judgment approving a divorce agreement which punished an ex-wife for subsequent cohabitation with a new partner. The implication of the provision was that a woman with a new (assumed to be male) partner would be supported financially by that partner. Justice Abrams wrote that since cohabitation could not be assumed to affect financial support without any evidence, cohabitation could not in itself result in an automatic termination of alimony. The opinion stated:

"A divorced spouse has no right to exercise control over a former spouse's life, and the court may not attempt to create such a right through the alimony provisions of a divorce decree."

On behalf of a majority, Judge Abrams wrote the 1997 opinion in E.N.O. v. L.M.M.,3 expanding the legal definition of family when the court granted visitation rights, after a break-up, to a woman who had helped raise her female partner's biological son. The decision looked to the explicit written coparenting agreement between the women but, more importantly, to the very close relationship the nonbiological woman had to the child, who called her "mommy." Not all of Justice Abrams's male colleagues joined her in that one, as there was a spirited dissent. Justice Abrams, though, while not seeking the limelight, was tenacious when she knew she was right.

Her opinions demonstrate a clear judicial philosophy. Our common-law system looks to precedents for principles which, applied to the facts of specific cases, yield just results. Justice Abrams was adept at identifying the key elements of prior precedents and adapting them to the particular facts which gave rise to the case before the court. Coming from a traditional family, she saw how the essence of traditional precedent required new jurisprudence as views of families and of women evolved. Massachusetts led the country, and the world, in recognition of the legal basis for new families, and Justice Abrams led the way.

Judge Abrams was not, however, an ideologue. She herself said that she was not an activist, as she was more interested in reaching the right result in the case before her. Judge Abrams wrote other far-reaching decisions regarding criminal law, landowners' rights, and minority rights.

Her opinions sprang from her empathy for everyday people. As just one example, in 1979, she wrote the opinion in the Uloth4 case. There, a fifty year old man working on the back of a trash truck lost a foot which was sheared off by the heavy metal plate that dragged the trash into the truck. The jury below awarded substantial damages to the injured worker for the negligence of the truck manufacturer in failing to design a safer mechanism. On appeal, the manufacturer argued that the mechanism was obviously and inevitably dangerous and the worker should have taken more care. Judge Abrams noted that the worker hardly had the power to dictate the terms of his work on the back of the dangerous truck, and wrote the opinion upholding the lower court's judgment.

Justice Abrams was renowned for her work ethic. When she was nominated for the Supreme Judicial Court, a story circulated among the bar about one late afternoon when the Judge (then "Ruth") was working in the Social Law Library in her role as special legal counsel to the Supreme Judicial Court. She became totally immersed in her work and didn't notice that everyone else had left and that the library was closed. She found the door locked and had to call a security guard to let her out of the library. The bar was satisfied that the Commonwealth would get its money's worth in elevating her to the Supreme Judicial Court itself.

Indeed, this work ethic was a hallmark of Justice Abrams's twenty-three years on the Supreme Judicial Court, during which she authored over 500 opinions. Arthur Miller, a renowned law professor, said that Justice Abrams "dedicated her entire life to law and the legal system through public service . . . . I have never really met anyone more dedicated to her job and to doing it right than Ruth."

Justice Abrams was also known for her clear, concise opinions. Justice Margot Botsford, who served with her on the Supreme Judicial Court, considered Justice Abrams a mentor and said that her opinions were a "model of clarity, completeness, and brevity. As is well recognized, brevity requires hard work and long hours."

Professor Miller and Justice Botsford were among the many leading members of the legal community with whom Justice Abrams maintained close personal and professional ties. She made it a point to build a network of other leading women in the law, a list that reads like a "Who's Who" of the most accomplished lawyers of her day.

Judge Abrams was central to the court's evolving view of families, not only by her opinions, but in her support for Chief Justice Margaret Marshall. Chief Justice Marshall tells of the day when she was sitting at her desk in the legal counsel's office at Harvard when Judge Abrams called her and suggested that she would make a great Justice of the Supreme Judicial Court and she should apply for the job, something Chief Justice Marshall had not previously considered. Chief Justice Marshall joined the bench and built on Justice Abrams's prior decisions in authoring the groundbreaking opinion in Goodridge v. Department of Public Health5 recognizing same-sex marriage as a constitutional right. By the time Justice Abrams left the Supreme Judicial Court, a majority of the Justices were women!

Justice Abrams leaves the bar an impressive legacy. Steeped in the law from her earliest days, through intelligence, hard work, and determination, she broke barriers, paved the way for others, and authored concise, insightful opinions which produced just results and protected essential rights of Massachusetts citizens, helping to set an example to the country and the world.

Hers is an inspiring legacy to the members of the Massachusetts bar, and to the citizens of this Commonwealth.

Mary K. Ryan, Esquire, addressed the court as follows:

Good afternoon Justices, Attorney General Healey, members of the Abrams family, friends, and colleagues.

May it please the court: Today, it is my honor to speak on behalf of the forty-seven women and men who had the privilege to clerk for the trailblazing pioneer Justice Ruth Abrams during her tenure on this court from 1977 to 2000. I hope each of them will find something in my remarks that resonates and triggers a warm recollection of their time with the Judge.

What did we learn from her? What are the lessons that have endured over the passing decades?

The most obvious answer is we learned a lot about the law. She was a brilliant lawyer and an accomplished writer. Though she had extensive experience in criminal practice, she thoroughly understood the civil side of the court's business and she drew on the latest academic writing on any issue. She was always aware of the current legal thinking -- she had after all first made her mark as a lawyer masterminding appeals in the Middlesex district attorney's office and then in the Attorney General's office. Ned has done a great job telling us about some of her seminal decisions. If I had to name only one case that I remembered from my year, it would be Packaging Industries v. Cheney,6 which so clearly elucidated the standard for preliminary injunctive relief that for years, it was the only case anyone ever cited on that topic.

I echo Ned's comments about how the Judge's practicality, common sense, and sense of justice and fairness played a role in how she thought about cases. You'll probably notice that most often I refer to Judge Abrams and not Justice Abrams. It is not out of any disrespect, and perhaps this changed over time, but as I recall, that was how she preferred to be addressed. Her jurisprudence as an SJC Justice was indelibly marked by the years she spent as a trial lawyer and trial judge. She was always interested in what practicing lawyers thought of her opinions. On more than one occasion, I remember her coming back from lunch and telling me she had run into this lawyer or that lawyer she knew and what they had to say about a new case or a big issue in the trial courts.

The other thing I absolutely know I learned from the Judge -- and I suspect I was not alone -- was how to write. She was a terrific writer but as anyone who knew her also knew, she was a perfectionist -- no opinion was done until it was actually published by the Reporter. And my clerkship was at the dawn of the computer age, before word processors made "cut" and "paste" electronic commands, not involving scissors and scotch tape or glue. When I was her clerk, Judge Abrams's office consisted of a large single room with a door opening onto one of the court's main hallways. When it was open, anyone going by could see directly into her chambers. I assume many often saw the Judge and her clerks engaged in deep discussion over a draft opinion which sometimes turned into a literal cut and paste exercise when the Judge decided that the paragraph she dropped yesterday in fact had the perfect turn of phrase to describe an important point in the opinion and we would be searching among the discarded drafts for a particular page. We certainly learned about honing language and the benefit of the last minute reread for style and clarity as well as substance. We also got our exercise running up and down to the Reporter's staff office on 13M with the latest edits.

The clerkship experience was also very enjoyable. For example, there was a tradition that once a month, the law clerks would go out to lunch with each of the justices in turn. The Judge loved the chance to get to know the other clerks. When it was time for the lunch with Judge Abrams, she consulted her clerks, as usual. I recall arranging for lunch in Chinatown. I knew the Judge loved spicy food so ordered plenty of it, to the point where there was barely anything that my tepid Irish palate could eat.

Clerkships are sought after legal positions not only because of the invaluable legal training but, equally important, for the opportunity to develop a professional mentoring relationship with your judge. The professional relationship soon became personal with Judge Abrams, because she was a warm and caring woman who became a friend and supporter to me, as she did for so many of her law clerks.

The Judge always had a strong interest in her clerks' personal lives and well-being. She expected us to work hard but she knew there was another side of life for all of us. She knew about spouses and children, schools and colleges, and in my case, brothers, nieces and nephews, an ill mother and then a widowed father who came to court to hear me argue my first case before the SJC when I went into practice. She told us all about her nieces and nephews too. And of course, her trips -- oh, how she loved to travel.

And I can certainly say that for me, as well as for Ned, this was a lifelong friendship. I can't remember all the different restaurants where we -- often the three of us -- met for lunch or dinner, but I know they included the legendary Marliave's off of Tremont Street on more than one occasion and a St. Patrick's Day lunch at Amrheins in South Boston, my home town, as well as the last time the three of us had dinner at Toscano on Charles Street while she still lived on Commonwealth Avenue. And in between, she came to our houses for dinner and even visited me on Cape Cod while we were both in Wellfleet on vacation. I still cannot believe I decided that making chicken cordon bleu for the first time was the perfect thing to serve when the Judge came to dinner with Ned and his wife at my Newton apartment in the early 1980s.

But the Judge had a special place in her heart for young women lawyers, and as her law clerk, I became one of the legion of women whom she mentored, sponsored, encouraged, cajoled, and promoted -- whatever you want to call it. I first met the Judge in a chance encounter in the Superior Court law clerks' offices in the "New Courthouse" in the fall of 1978, when I was the chief clerk. Soon after, the Judge called to offer me a clerkship. I was thrilled but hesitated about clerking for another year. What she did next amazes me to this day. The Judge took the time to invite me to her office to tell me all the reasons why the job would help my career, including the fact that some of the most accomplished women lawyers she knew, who had gone on to become highly respected judges, had clerked for several years in the early days of their careers because not a single law firm would hire them. After that, I couldn't say no. I have no doubt that job changed the path of my career for the better, for which I will be eternally grateful.

And the stories she told me that day offered just a glimpse of the rich history she continued to share throughout the time I knew her. When I clerked for her, she sometimes invited me to join her for dinner with her women judge friends -- because she was generous and kind and she thought I should know these fabulous women pioneers and appreciate their history: Superior Court Judges Eileen Griffin, one of her traveling companions at the time, and Katherine Izzo, are the two I remember, though I know she often spoke of Justices Raya Dreben and Charlotte Perretta, among others -- after all, she really did know just about every woman lawyer and judge in those days. It was at these dinners that I heard many stories about the "not-so-good" old days, including how they agonized over whether they needed to wear hats and gloves to court. I gathered that was the equivalent of the "can I wear pants to court" question for women lawyers in the 80s and 90s.

Judge Abrams seldom spoke about specific instances of discrimination or barriers she had encountered in what was essentially the all-male legal world she entered in the early days of her career, but she understood very well that even decades later, it would be a lot harder for women to reach the pinnacles of professional accomplishment.

My clerkship year was when I first learned how deeply committed Judge Abrams was to opening the doors for those who followed in her path. Many of the most prominent judges in the Commonwealth have spoken of the personal encouragement she gave them to apply for the bench, including former Chief Justice Marshall, who credits Judge Abrams with transforming the face of the Massachusetts judiciary with her constant work to get more women and minorities appointed to the bench.

That's the tip of the iceberg, because much of what Judge Abrams did was behind the scenes. This was totally consistent with her modest, unassuming personality and her avoidance of the limelight. Many might consider her most memorable legacy to be the personal support she gave to women trying to establish themselves or advance in the legal profession, whether as judges, lawyers, or court clerks. She was a mentor for men as well as women, but she was passionate about breaking down the barriers to women achieving the highest echelons in the profession.

She made no bones about the fact that she thought the law was still too much of a man's profession even when she was on this court, and she became the strongest ally and supporter for women lawyers -- and indeed, all women in the legal system -- that this State has ever seen.

One way she did this was by using the power of her office to do whatever she could in her official role.

Judge Abrams cared about how the law affected the lives of every woman impacted by the legal system, not just women lawyers. Thus, she became one of the moving forces behind the Massachusetts Gender Bias Study in the late 1980s. Pat McGovern, then the Senate Chair of Ways and Means, gives Judge Abrams all the credit for securing the funding for the study and cites her critical role in making it happen. Judge Abrams went on to serve as co-chair of the study and then chair of the Committee for Gender Equality in the Courts.

Another way Judge Abrams quickly realized she could influence a woman's career was to ensure equal opportunity appointments within the courts and to prestigious committees appointed by the SJC itself, such as the Board of Bar Overseers or the Committee for Public Counsel Services (formerly Mass Defenders). Judge Abrams was justifiably proud that many women who went on to be judges or bar presidents were tapped to serve on these important committees.

I also remember many times when Judge Abrams would say that she'd been the one to ask the simple question -- why aren't there any women on this committee? Or simply, why aren't there more women? She would insist that lists of proposed candidates be sent back so that the bar associations could add more women. Or to her friends on Beacon Hill, the question was "why aren't there more women on the bench?" Hers was a much needed voice in a power structure that had never had a female voice before.

For such a tiny woman, she had a huge impact that went far beyond her circle of law clerks, colleagues, friends, and acquaintances. So, today, we remember Ruth Ida Abrams. She was a great friend and mentor to each and every one of her clerks, but she was so much more than that. She built a bridge between her generation of pioneering women and the next and future generations of women lawyers. Her name will be spoken whenever the story of how women broke the barriers to becoming full participants in the legal community is told, and for that, we are all grateful.

Retired Chief Justice Herbert P. Wilkins responded for the court as follows:

Members of the court, Attorney General Healey, Mr. Notis-McConarty, Ms. Ryan, members of the Abrams family, and guests.

Ruth Abrams and I served together on the court for twenty-two years. Relatively few Justices have served twenty-two years. Even fewer have served together for that long. I am honored to reply on behalf of the Justices.

When Ruth Abrams joined the court on the first day of February, 1977, she entered an institution that had been exclusively male for more than 250 years. By example and with quiet determination, she showed the way for women in the law generally and in the judiciary in particular. Because of the various positions she held before her arrival at the court and because the law was an important part of her family, Ruth was well qualified to meet the challenge of being the first female Justice.

That is not to say that there were no problems. There were insensitive comments from time to time. Most were thoughtless. None was appropriate. Ruth quietly endured these moments (at least within the court). In time they became less frequent.

Ruth focused on big issues that matter to women. One day I asked her whether we should do something about that provision in the ancient lawyers' oath by which new lawyers agree that they "will delay no MAN (emphasis supplied) for lucre or malice." Ruth promptly replied that there were more important matters to deal with before we got to that.

Finally there was change. More women were admitted to the bar, were appointed to court committees, became trial lawyers, argued before the court, and became lower court judges. Women became clerks of the Commonwealth court and the county court. For years, however, Ruth remained a lone pioneer on the court, setting an example and urging the cause of women generally and specifically to her colleagues. It was more than twenty years before another woman was appointed a Justice of the Supreme Judicial Court.

Discussion of Ruth's importance to women in the law of the Commonwealth should not obscure the fact that she was a fine appellate judge. She wrote carefully, clearly, and thoroughly. One year a study showed that her opinions on average were two or three pages shorter than those of most of her colleagues.

To the surprise of some, Ruth was interested in sports. She regularly attended Harvard football games. Many a Monday morning, especially in the earlier years, we commiserated about what had happened in Harvard stadium on the previous Saturday. Ruth joined the Friends of Harvard Hockey. When, in one rare year, Harvard was headed west to the national championship playoffs, Ruth received, but declined, an offer to travel on the team's chartered flight.

In conclusion, I note that it must have been with considerable satisfaction to Ruth when, at the court's September, 1999, sitting, the Chief Justice position being vacant, as the senior Associate Justice, Ruth presided. Perhaps she felt even greater satisfaction one year later when, just before her retirement and for the first time in the court's history, a majority of the Justices were women.

On behalf of the Justices of the Supreme Judicial Court, the motion of the Attorney General is allowed, and this Memorial is to be spread on the records of this court.

Footnotes

- Massachusetts Elec. Co. v. Massachusetts Comm'n Against Discrimination, 375 Mass. 160 (1978).

- Gottsegen v. Gottsegen, 397 Mass. 617 (1986).

- E.N.O. v. L.M.M., 429 Mass. 824 (1999).

- Uloth v. City Tank Corp., 376 Mass. 874 (1978).

- Goodridge v. Department of Pub. Health, 440 Mass. 309 (2003).

- Packaging Indus. Group, Inc. v. Cheney,380 Mass. 609 (1980).