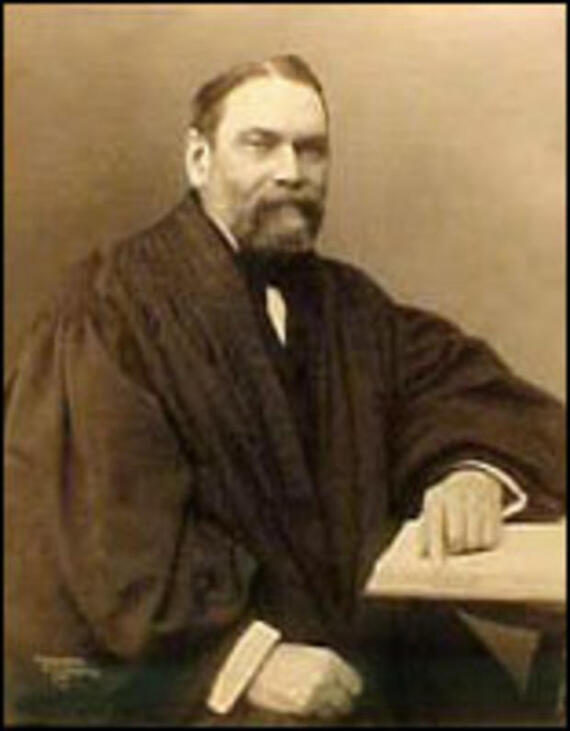

Marcus Perrin Knowlton

Chief Justice memorial

231 Mass. 615 (1919)

The Honorable Marcus Perrin Knowlton, an Associate Justice of this court from September 14, 1887, until December 17, 1902, and the Chief Justice of this court from December 17, 1902, until September 7, 1911, died at Springfield on May 7, 1918. On March 22, 1919, a special sitting of the full court was held, with all of the Justices present, at which there were the following proceedings:

The Attorney General addressed the court as follows:

May it please your Honors: I appear on behalf of the bar of the Commonwealth to present to the court the memorial prepared by a committee of the bar, in which it has been sought to embody the expression of the bar's respect for the character of Marcus Perrin Knowlton, lately Chief Justice of this court, and its appreciation of him as a man and as a magistrate.

In the discharge of this duty it is not fitting that I amplify the memorial. The details of his active life are adequately set forth therein, and there seems little to be added. In the presence of those who knew him intimately during his life, it does not become me to attempt his eulogy. That grateful duty has been appropriately assigned to others.

As an officer of the Commonwealth, however, I desire to express her gratitude for the distinguished service rendered by him, who, not long since, was the chief of her jurists. Over thirty-nine years of his life were devoted to public service. After serving in both our House of Representatives and Senate, he was appointed a Justice of the Superior Court, and from that court was elevated to the Supreme Judicial Court, where he served for twenty-four years, during over eight of which he was Chief Justice. His service was marked by industry, keen and penetrating thought, clarity and conciseness of expression, rare tact and unfailing courtesy. On the seventh day of May, last, by his death, the Commonwealth lost a beloved and distinguished citizen. On that day a life of exceptional and worthy achievement closed, a life devoted for the most part to the public service, a life whose obligations were met with courage, firmness and fidelity. It is, indeed, fitting and appropriate that the bar and the court, representing an appreciative public, should take action to commemorate such a life. Lives like his make for the betterment of the character of our people and strongly influence our civilization. His work is done; its influence lives on. His life and character will serve as an inspiration to the living.

I now have the honor to present the memorial.

The Attorney General then presented the following memorial:

Marcus Perrin Knowlton, the son of Merrick and Fatima (Perrin) Knowlton, was born in Wilbraham, February 3, 1839. He was fitted for college at Monson and was graduated at Yale in the class of 1860. His standing in scholarship was high and of even excellence in all the courses of the curriculum. In English composition he was unexcelled.

As a student he was grave, modest and reserved in his bearing, yet always kind, courteous, untiringly industrious, self-reliant and independent. He was faithful to every duty and every obligation. He was morally sound. This integrity in all things lasted without abatement to the end.

On September 24, 1862, he was admitted to the bar in Hampden County.

Thereafter his home was in Springfield. In the practice of law his success was immediate. The firm of Stearns and Knowlton and its successor, Knowlton and Long, were among the leaders in western Massachusetts. His intellectual powers matured early and knew no waning to the day of his death at Springfield on May 7, 1918.

He served in the City Council and represented his district both in the House and Senate.

As a lawyer he was an alert, prudent and sagacious counsellor with a wide knowledge of affairs, industrious and, above all, gifted with a rare common sense which gave working efficiency to his natural and acquired powers.

His conservative influence in the Legislature attracted general attention and approval, and in 1881 Governor Long with an instinctive appreciation of his fitness, appointed him a Justice of the Superior Court. He was then forty-two years of age. To the bar of eastern Massachusetts he was a comparative stranger. Hardly had he taken his seat upon the bench before, as in the case of Chief Justice Bigelow, the bar recognized in him with unqualified satisfaction those qualities that make a successful nisi prius judge. He had deep special learning and wide general scholarship.

On the bench he was amazingly quick of apprehension, patient and attentive. He was transparently impartial. He had good judgment. He was a master of clear and orderly statement. His temper was equable. He had unusual mental and physical endurance. His industry was tireless. He worked without haste and without rest. His voice was well modulated and in it there was never a fretful note. His manner was dignified but gracious, his smile attractive but with no suggestion of levity. He was serious and sincere in all things. He had an intuitive sense of propriety. He had self-reliance without aggressiveness or arrogance. He had tact without cunning. He was a reader of the motives of men. With members of the bar he was cordial and friendly but not familiar.

He learned the time-saving art of stenography and his brief trial notes in shorthand usefully corroborated his retentive memory. In his court there was no wrangling. The supremacy of the bench was self-evident.

The rare combination of all these admirable characteristics made him an ideal trial judge. His was the twenty-second appointment to the bench of that able court.

He was appointed an Associate Justice of the Supreme Judicial Court on the fourteenth day of September, 1887, and was promoted to its Chief Justiceship in 1902 which position he held till his resignation by reason of an accident impairing his eyesight, on September 7, 1911, in the seventy-third year of his age. His resignation was universally regretted.

Thereafter he lived a quiet but not an idle life till the end came on the seventh day of May, 1918, in the eightieth year of his age.

He was honored with the degree of Doctor of Laws by his alma mater Yale and by Harvard and Williams.

By birth, education and environment he was a typical New Englander. He was proud of her history and institutions. He believed in the saving common sense of her people and had an abiding faith in her future. He was a conservative influence in the Commonwealth.

His work on the supreme bench was well and properly done. He was ambitious to excel not others but himself. He strove each day to better the work of yesterday and with the passing years he grew in worth. His fame with those who are to come after us will rest upon his written opinions. They are his monument, more enduring than bronze. They are unimpeachable witnesses to his greatness as a judge. They deservedly sustain the high reputation of a court whose decisions are cited with respect wherever the common law holds its seat.

He was a good son, a good father, a good husband, a good friend, a good neighbor, and a patriotic citizen.

Such a life is worthy of commemoration.

As a deserved tribute to the memory of Honorable Marcus Perrin Knowlton, the bar of the Commonwealth prays that this memorial be made a part of the records of this court.

Honorable Charles L. Long then addressed the court as follows:

There is, in the town of Wilbraham, a range of hills, which cover an area of many square miles, and which, for a long period of time, have been honored with the dignified name of "Wilbraham Mountains." High up among them, in a poor farming section called Glendale, is a small farm, on which is an unpretentious one story house, having but two living rooms on the ground floor, and, above them, immediately beneath the rafters, such meagre sleeping accommodations as the limited area allows. In that humble dwelling, Chief Justice Knowlton was born.

When he was but five years of age, his father sold the farm on which the family had lived, and purchased one in the adjoining town of Monson, on the road leading from the village to Palmer. It was there that he spent his boyhood days; about which little is known, or can be learned, as he was the last survivor of the family.

The period of elementary study having passed, young Knowlton entered the Monson Academy, an educational institution of repute then, and now, existing in the village of Monson, where he fitted for college. His father did not finance his college course. That he accomplished himself; and nothing more forcibly shows his youthful persistency and ability than the industrious manner in which he worked his way through college. For this purpose, he resorted to teaching. He taught in the Westfield Academy one term, during his junior year, without interrupting his studies; and, during his senior year, he was instructor in mathematics in the Hopkins Grammar School in New Haven.

At college his rank was high. In his class at Yale, graduating one hundred and nine, he stood twelfth; in his junior and senior years he took third oration stand; and in his sophomore year received second prize for English composition. He was a member of a freshman society known as Gamma Nu, of the Phi Beta Kappa and of the Brothers in Unity; and for three years maintained his physical well-being by dining at an eating club called "The Mackerels."

Having for a short time after his graduation performed the duties of principal of an institution then known as the Union School and located at Norwalk, Connecticut, his career as a teacher terminated by the destruction, by fire, of that institution's educational edifice. It was then that he turned his attention to the study of that profession which was to be his life's work, and which, at the bar and on the bench, was to be crowned with abounding success.

The office chosen by him, in which to begin his work as a law student, was, indeed, a modest one. It was located in the village of Palmer, in a little one story office building such as lawyers and doctors were, in those days, apt to occupy in the hamlets of the country; and was presided over by James G. Allen, a highly honorable county lawyer of excellent character, but of limited ability and practice. Evidently, young Knowlton soon realized the advisability of studying under the guiding influence of abler and wiser minds; for he left the office of "Squire" Allen, and entered that of Wells and Soule in Springfield.

It would have been impossible for him to have chosen more wisely; both members of that firm were men of high standing for ability and uprightness; and both subsequently became justices of this court.

Judge Knowlton absorbed a knowledge of the law rapidly, and speedily gained admission to the bar. He was then of a frail constitution, inclined to pulmonary trouble, which continued to threaten him for several years and which demanded of him the most careful attention to his habits of life. To this demand he faithfully responded, with the result, that, in his subsequent years, he became possessed of a constitution and physique which enabled him to accomplish a vast amount of professional and judicial work.

His career at the bar began by opening an office and practising by himself. Within two years the firm of Knowlton and Greene was formed; but this was not of long duration; and, on being terminated, the firm of Stearns and Knowlton was established. Mr. Stearns was a brilliant lawyer, with a large practice, both civil and criminal. In the latter branch of the law he had acquired a great reputation, owing to the large number of cases he had defended, the importance of many of them, and the unusual success which had crowned his efforts. Friends of Judge Knowlton questioned the wisdom of his associating himself with Mr. Stearns by the formation of that firm. The doubt they entertained had for its foundation the radical difference, in habits, temperament and views of life, of the two men.

Notwithstanding these differences, each judged accurately of the value of the other as a business associate. The firm was a great success, professionally and financially; its field of activity was western Massachusetts; its reputation extended throughout the Commonwealth, and it continued, for many years, the leading law firm of western Massachusetts.

In the practice of the law, Judge Knowlton was exceedingly conscientious. Suits were not brought unless he was convinced that they possessed merit. He prepared his cases with great care and thoroughness; he tried them with marked ability, and all questions of law were ably argued. Clients had confidence in his judgment and uprightness, and jurors held him in high esteem.

It cannot be said that politics ever had any attraction to Judge Knowlton; and the services he rendered as a member of the Springfield city government, as a representative, and as a senator in the General Court of Massachusetts, were not the outgrowth of political ambition; but resulted from his willingness to do his share of public service and a desire to familiarize himself with the way in which those branches of government were conducted.

At the time of his appointment as a Judge of the Superior Court, he was unfamiliar with the principles of stenographic writing; indeed, he had never used a stenographer in the transaction of his business; nor had any other lawyer in his section of the State. Realizing the probable usefulness of that art in the position to which he had been appointed, he obtained a treatise thereon, plunged into the study thereof, and so speedily mastered the subject that he was, in a very short time, able to use the same in taking notes of the evidence presented in the trials of cases before him; and, later, while a Justice of this court, he would, he informed me, write his opinions in shorthand and leave them with a typist, who, being able to read his stenographic characters, would transcribe them in typewritten form.

The wisdom of the appointment of Judge Knowlton to the bench of the Superior Court was speedily manifest. His ability to analyze evidence, his mastery of the law, the absolute impartiality and clearness of his charges to the jury, his honorable and courteous treatment of the members of the bar engaged in the trial of causes before him, and his abiding love of justice, soon convinced all who knew him, that his field of judicial activity could not long remain in the Superior Court, but would be found in the highest branch of the judiciary of this Commonwealth. Little surprise was there, therefore, when he was appointed a Justice of this court; and when, later, he became Chief Justice, it was universally recognized that his ability made his appointment to that position eminently wise.

When a man enters upon the duties of a Justice of this court, he becomes famous because of the quality of the work he performs in the hearing and decision of the important cases which come before him and of the opinions he writes which appear in our Massachusetts Reports. He has little time for social matters, and becomes less and less familiar with the faces, and has less and less knowledge of the people of the community in which he lives. Indeed, his high judicial rank seems to have the effect of causing the people to refrain from that freedom of social intercourse which formerly existed, and to treat him with a reserve which they seem to feel better becomes the dignity of his high judicial position.

While a great many recognized Chief Justice Knowlton as they would, from time to time, see him upon the streets, the number whom he knew was much less; and this caused him to say to me that there were few in the city in which he lived whom he knew and to remark to another that he was acquainted with such a limited number that, if he were to die, there would be but few who would attend his funeral. He seemed absolutely to have failed to appreciate the reputation which had resulted from the work he had accomplished and the ability he possessed. Others, however, fully recognized it. The two great universities of New England, as well as Williams College, paid tribute to his greatness; and the Massachusetts Bar Association, representing the entire bar of the Commonwealth, honored his name, by resolutions, by addresses, and by presenting to the county of Hampden his life-size portrait which now adorns the walls of the Court House in Springfield.

An affliction of the eyes, from which he subsequently recovered, caused Chief Justice Knowlton to resign his judicial position. Thereafter, until his death, he resided in Springfield, surrounded by all those comforts which an abundant property could bring to a man of his advanced years. His mind remained strong until the last; and, to a remarkable degree, he retained his physical strength until his final sickness. True, there was some slight impairment of the latter; but it was only nature's way of calling his attention to the fact that he had entered the domain of old age. This impairment was not so apparent to his friends, but was noticed and referred to by him. For a few weeks prior to his death, his physical strength seemed to be yielding to the attack of time. He grew feeble, became confined to his home, and, finally, in his eightieth year, after a terminal sickness of about two weeks, passed beyond our vision, into the great and mysterious unknown.

To my mind, he was, during all of the many years it was my privilege to know him, a follower of that rule which commands us to do unto others as we would that others should do unto us. The public at large, among whom he lived for so long, will remember him for his honest, upright and useful life; and the bar of the Commonwealth, now existing, and that of generations to follow, will view with admiration, the mind of the man whose clear, logical and convincing legal views appear in the many opinions written by him during his services upon the bench of this court, and which are to be found in sixty-five of the volumes of our Massachusetts Reports.

The Commonwealth loses by the death of such a man. The example of his life, his devotion to duty, the ideals for which he stood, his universal uprightness and his industrious habits should be an inspiration to those of us who survive him and long remain a guide to those who, surviving us, shall take up the burdens of life as we shall lay them down.

Honorable Robert M. Morse then addressed the court as follows:

I made the acquaintance of the late Chief Justice in 1880. At that time we were both members of the Legislature and I had frequent opportunities to observe and admire his diligent and conscientious devotion to his important work, his legal acumen, his good sense and sound judgment and the charm of his personal intercourse. This early acquaintance ripened rapidly into warm friendship which grew still closer as the years went on and lasted throughout his long and honorable judicial career. He was a singularly likable man, modest, genial, interesting in conversation, with a ready smile and sparkling eye which lighted up his countenance and revealed the warmth of his nature. He showed himself at once equal to the serious responsibilities reposed in him as judge. If he was dealing with facts he was quick in analyzing complicated evidence and in reaching accurate conclusions. If he was considering legal propositions and hearing conflicting arguments he listened courteously and questioned intelligently. In the determination of cases he omitted no labor or research in examining not only all the authorities which had been called to his attention but all others which his ample legal learning suggested. His mind was well balanced, his industry was wonderful and his sense of justice profound. When, after weighing carefully opposing arguments in the light of all the study and examination which he had given them, he reached a conclusion, he stated it in an opinion expressed in clear and terse language and which carried with it the voice of authority. But in this presence it is as unnecessary to recount his supreme merits as a judge as it is impossible to express adequately the great sense of loss which his death has occasioned to us all.

William H. Brooks, Esquire, then addressed the court as follows:

I can add nothing of moment or interest to what has been so well expressed in the memorial just presented, the admirable biographical contribution, and the utterances of the distinguished gentlemen who have preceded me.

But, in view of the invitation extended to me by the Massachusetts Bar Association, I cannot forbear a brief individual tribute to the memory of the late former Chief Justice of our Supreme Judicial Court.

We are prone, I think, to speak of the dead, whom living we admired and respected, in terms which might appear to some of exaggerated praise. I shall endeavor to refrain from that error, for I know that Judge Knowlton would have deplored fulsome eulogy.

When I was admitted to the bar -- more years ago than I like to contemplate -- Judge Knowlton was engaged in the active practice of his profession. He did not participate in the actual trials of many causes, but he had the repute of possessing the capacity and inclination for extended intellectual labor, for research and for common sense and good judgment. He was famed as a safe counsellor. He was then at the zenith of his professional career.

The positions in public life which he then filled or to which soon afterwards he was chosen he regarded as public trusts, to be administered honestly, faithfully and conscientiously.

Before his elevation to the bench he seemed to me cold, calm, collected but courteous and considerate. He always seemed judicial. I never saw him when I thought he was either excited or perturbed. I do not remember his ever perpetrating a witticism or laughing aloud. The sense of humor was apparently absent or dormant. He had at times a smile kindly and alluring. His statements of propositions and questions in dispute were felicitous, direct and simple. After he became a judge there appeared no noticeable change in his demeanor except perhaps an additional seriousness.

In the brief time allotted, but little can here be said of the much that might well be said of him, the great magistrate. Much learning, much thought, it is said, has a tendency to cause the possessor to seem austere and unapproachable but, as I have already suggested, there was little, if any, change of characteristics from Mr. Knowlton, the practitioner, to Justice Knowlton, the judge. He was a human judge, a lover of justice and fair play; patient, tactful, helpful but ever firm and earnest.

One of his noble and endearing traits was the endeavor to render so far as was consistent with the proprieties of his position the unfamiliar pathway less arduous for the youthful and slightly experienced lawyer. But to the faults and mistakes of those of larger experience, who should have known better, he was not so complaisant.

His powers of application and concentration were proverbial, his ability for differentiation, discrimination and assimilation was well recognized.

His court opinions found in sixty-five volumes of our reports are of wide range, dealing with many intricate and diverse subjects. They are lucid and certain and of such nature that they are helpful and authoritative in cases other than the then instant case. He used language to express ideas and that did not confuse them. These opinions are treated with the utmost respect in other jurisdictions. He has added honor to our courts and learning to the law.

Mr. Webster, I think, said that he believed that "there is no character on earth more elevated and pure than that of a learned and upright judge and that he exerts an influence like the dews of Heaven falling without observation."

The subject of this memorial then, though dead, will continue to live in the impress he has left upon the law and in the masterly judicial opinions that he has written and in the influence that they do and will yield.

Moorfield Storey, Esquire, then addressed the court as follows:

My recollection of Chief Justice Knowlton goes back to the time when I first met him as a judge of the Superior Court presiding at the trial of a case in which I was counsel, and by that first experience of his quality were planted the seeds of a respect which grew with every year of his life. He was one of the best nisi prius judges that ever sat on the Massachusetts bench. His control of a trial was remarkable. He held counsel to their work, and discouraged most effectively those passages between them which take time, create ill-feeling, cloud the issue and awaken a feeling of partisanship in the jury. To him the court room was a chamber devoted to the ascertainment of truth, not "an arena for the exhibition of champions," much less a place for unseemly quarrels between officers of the court. His rulings on questions of evidence were prompt and, once made, were not changed, his instructions to the jury were clear, his manner was calm and dignified, his courtesy unvarying, his work as a judge in all respects well done.

His record in the Superior Court made his promotion to the supreme bench inevitable, but when it came the pleasure with which we all regard the recognition of great merit and distinguished service was tempered by sorrow at the great loss which the trial court had sustained.

In the Supreme Judicial Court, both as an associate and as Chief Justice, he added to his reputation and to the reputation of the court, and on his knowledge of law, his strong common sense and his keen appreciation of justice the citizens of the Commonwealth pinned their faith for years. When an affection of his eyes, fortunately less serious than was feared, led him to resign his seat, the news was received with universal regret that we had lost a judge of such character, such ability and such ripe experience.

After he had left the bench and at an age when he was well entitled to enjoy the repose which he had so richly earned, he recognized the call of duty when he was asked to undertake the tedious and thankless task of trying to reorganize the bankrupt system of the Boston and Maine Railroad. He applied himself to the work with characteristic ability and patience and with an energy and industry surprising in a man of his years, and we may well hope that the result to which he contributed so much may prove of lasting benefit to all the States which are so largely dependent on that great railroad.

A man of the best New England type, simple, sincere, direct in his methods, free from any taint of self-seeking or self-advertisement, with a high sense of duty and great public spirit, he was a model citizen as well as a great magistrate.

While he lived he enjoyed in a high degree the respect and regard of Massachusetts, and when he died he left behind him a record of distinguished public service which the Commonwealth must ever be proud to remember.

Chief Justice Rugg responded as follows:

Mr. Attorney General and brethren of the bar: It is well for the bench and bar on appropriate occasions to pause in the midst of labors and say, with the sage of old, "Let us now praise famous men, . . . . men renowned for their power, giving counsel by their understanding, . . . Leaders of the people by their counsels, and by their knowledge."

There is singular fitness in paying tribute to the memory of the late Chief Justice Knowlton. For thirty years, in high judicial position upon two courts he served the public weal. The character of his work has given distinction to his name and has added lustre to the reputation of the Commonwealth. He was fortunate in his ancestry, birth and early life. The traditions of generations of strong New England forbears were his. He was born among the hills in the valley of the Connecticut. He had the priceless patrimony of the farmer lad in the training in self-reliance, resourcefulness, manual toil, and close touch with nature. His physical and intellectual fibre were strengthened by the free life which the farm offers to the healthy boy. Fitted for Yale College at Monson Academy, he was during many of his later years a member of the board of trustees of that institution. He maintained a high rank in his college class and was among the first dozen of its members in general excellence as a student throughout his course. His professional activity and association in Springfield brought him in close contact with the able men of an exceptional bar. He came to maturity familiar with the common concerns of life and enjoying a wide knowledge of men and affairs.

After six years upon the bench of the great trial court of the Commonwealth, he was appointed at the age of forty-eight an Associate Justice of this court, on the fourteenth of September, 1887. He became Chief Justice in December, 1902, and resigned on the seventh of September, 1911. The period of his service on the Supreme Judicial Court fell seven days short of twenty-four years.

Only five members of this court under the State government have performed such duties for a longer time. It is more than fifty years since the last of these passed from the scene of his earthly labors. They are: Samuel S. Wilde, 35 years, from 1815 to 1850; Lemuel Shaw, 30 years, from 1830 to 1860; Charles A. Dewey, 29 years, from 1837 to 1866; Samuel Putnam, 28 years, from 1814 to 1842; and Isaac Parker, 24 years, from January 28, 1806, to July 26, 1830.

A mere statement of the details of Chief Justice Knowlton's labors upon this court is impressive. His written opinions are to be found in sixty-five volumes of the reports, the first being O'Keefe v. Northampton, reported in 145 Mass. 115, and the last, Ryan v. Boston Elevated Railway, 209 Mass. 292. The number of opinions written by him expressing the judgment of the court in decided cases was eight hundred and thirty-seven as Associate Justice and seven hundred and thirty-three as Chief Justice, making a total of fifteen hundred and seventy. The number of his dissenting opinions was twenty-nine, only four of which were delivered while he was Chief Justice. It is interesting to note that the opinions of Chief Justice Shaw, serving six years longer, are to be found in fifty-five volumes of our reports, beginning with 9 Pick. and ending with 15 Gray, and that the number bearing his name was twenty-one hundred and sixty-one. No other member of the court has approached very near to either of these in number of opinions written. No other magistrate in the history of Massachusetts has contributed so much to the visible fabric of our jurisprudence as did the late Chief Justice, with the single exception of Chief Justice Shaw.

Number of opinions written by itself alone is a slender measure of judicial accomplishment. It may be simply evidence of industry and ease of composition. Quality of work is the real test of achievement. Gauged by the most exacting standard the late Chief Justice was in the first rank of great judges. His knowledge of law was extensive and profound, his discernment of legal analogies was quick and accurate, his reasoning powers were of the highest order. His vision was broad, his poise unperturbed, his perception keen, and his apprehension of the ultimate reach of principles unclouded. While his memory of decided cases was not extraordinary, his grasp of fundamental doctrines was wide and sure. He saw them plainly. He appreciated to an exceptional degree their bearings in application to shifting facts and changing conditions. The motions of his mind were rapid and his intellectual processes accurate; but he was patient and painstaking. His written judgments combined in rare degree clearness of thought, lucidity of expression, and insight as to governing principles. A remarkable brevity was his: it excluded everything superfluous and omitted nothing essential. The style of his composition was a near approach to the ideal. His vocabulary was made up of plain words in common use. His sentences were not protracted and were never involved. His language was unobtrusive. His diction was pure. In reading what he has written one thinks only of the ideas expressed and never of the medium through which they are conveyed. He seldom wrote long opinions. His thought was clear and concise. He was able to express it in such luminous phrase that it could not easily be misunderstood. He compressed into narrow compass the controlling rules of law with sufficient completeness of definition for the decision of the case at hand. His statement was comprehensive in its sweep. He dealt ordinarily with main propositions and did not undertake to cover subsidiary ramifications. He realized that a short opinion is more inviting to the eye than a long one and therefore more likely to be read and to influence the currents of legal thought and action. He understood that the power of plain and terse expression of important legal doctrines is an attribute of no mean value. There was no redundancy either in his thought, his speech or his writing.

He possessed attainments in scholarship. But he was thoroughly grounded in the practical. He tested every argument by its effect upon the affairs of everyday life. The wisdom of the marketplace was his. He had insight into human nature and intuition of the secret springs which move men to action. He read the newspapers constantly and kept in touch with all that was passing In the world. Great common sense was his and it never deserted him. However much he may have enjoyed philosophical speculations or the beauties of logic, he never lost sight of the fact that the law is a practical science designed to promote the general welfare, to conserve the common happiness, to preserve public and private safety, and to protect all the people in the enjoyment of life, liberty and property. The sense of justice was instinctive with him. Of course he was no respecter of persons. Each litigant stood before him alike indifferent. He did "everything for justice, nothing for fear or favor." He recognized the necessity that the courts in performing their duties look to the present and to the future and not exclusively to the past. In a published article he expressed his own conception of the judicial function in these words: "With all the conservatism that is necessary in adapting new laws to existing conditions and the customs of the people, the courts have gone forward hand in hand with the law-making power to create a system of jurisprudence that shall be worthy of a people of the highest intelligence. While statutes have been enacted for the simplification of procedure, the courts of their own motion have often disregarded precedents in non-essentials and have sanctioned the omission of unnecessary verbiage and have encouraged the statement of facts without formality, in clear and simple terms. . . . The distinctive feature of the common law is that it is a growth, which has always adapted itself to new discoveries and changed conditions and which is still capable of boundless expansion and adaptation to meet the requirements of a changing world."

As Chief Justice his administration of the business of the court was efficient. Its work went forward with due deliberation, without friction, without haste and without delay. He had a faculty of harmonizing divergent views and of convincing differing minds.

He approached the consideration of every question of constitutional law with the comprehension of a statesman. He examined it from every point of view. His numerous opinions upon this branch of the law in general have been confirmed in their soundness by the test of experience and by analytical criticism and review. In consultation with associates the scope of his reasoning and his elucidation of the underlying foundations of the law revealed a powerful intellect, of marvelous range and incisiveness, of great quickness and precision and of wide vision and sound judgment. His attitude was that of mutual conference and helpfulness. Under his guidance discussion never degenerated into controversy. When the likelihood of further enlightenment had closed, the time for final decision had come. His impulses were generous. So far as lay in his power, everybody was accorded kindness as well as justice.

After retirement from the bench his business sagacity received signal recognition in his selection by the federal court as chairman of the board of trustees whose duty involved for several years in part the management and reorganization of the Boston and Maine Railroad.

He was a man of firm conviction and steadfast adherence to his matured conclusions. But he was open minded so long as any new arguments were available. He was of dauntless courage and never hesitated to stand alone, if need be, on what seemed to him to be the sound ground. His manner both upon the bench and elsewhere combined graciousness with dignity. His deportment toward the bar was unexceptional.

The performance of judicial work was the absorbing element of his life. He was not much given to the making of public addresses, although whenever he spoke, it was with the strength of elevated thought. The papers prepared by him for The Club in Springfield, of which he was long an interested member, manifest breadth of literary taste and intimate familiarity with the best of English literature.

The history of British and American political institutions was to him an attractive field for study. He was imbued with the spirit of Massachusetts. He knew thoroughly the annals of her colonial and provincial periods and her legal, social and industrial growth and development under the State government. When he declared her law, he spoke as one skilled in all her lore.

His sympathies were deep and broad. He enjoyed the activities of out of doors. For many years he was an habitual horseback rider. Latterly he recruited his strength on the golf links. He was of medium height, erect in carriage, of alert and elastic step. His raven hair and slightly silvered beard gave him the appearance in later life of one much younger than he was.

The great historian of European morals has said that "no character can attain a supreme degree of excellence in which a reverential spirit is wanting." The late Chief Justice was constant in his attendance upon public worship. He manifested thereby not only a firm belief in the eternal verities of religion, but an abiding reverence for whatever things are holy and of good report. His blameless character, his lofty ideals of personal, civic and official duty, and the simplicity of his life, commanded the respect of the public and endeared him to those who were privileged to have an intimate acquaintance with him.

A few years ago a justice of this court, since retired, said to a leader of our bar, whose reputation was also national, "I think the time will come when the bar will regard Chief Justice Knowlton as the equal of Chief Justice Shaw." The reply was, "That time has already come." In different generations, under widely changed conditions, each of these great chief justices in his own way with talents adapted to the times contributed in signal degree to the development of our jurisprudence.

It is with consciousness of deep veneration and profound personal obligation that I have been the voice of the court in speaking of Chief Justice Knowlton. Possibly this feeling has colored what has been said; but it seems an inadequate characterization of a mighty man and an eminent judge. He was vastly more than our words declare. Fortunate indeed is the State whose life has been enriched by the prolonged services of such a judge.

The motion of the Attorney General that the memorial be extended upon the records of the court is granted.

The court will now adjourn.