I. The Internal Special Audit Unit

The OIG is an independent agency charged with preventing and detecting fraud, waste and abuse in the use of public funds and public property. Created in 1981, it was the first state-level inspector general’s office in the country. In keeping with its broad statutory mandate, the Office investigates allegations of fraud, waste and abuse at all levels of government; reviews programs and practices in state and local agencies to identify systemic vulnerabilities and opportunities for improvement; and provides assistance to both the public and private sectors to help prevent fraud, waste and abuse in the use of public funds.

The Office’s Internal Special Audit Unit monitors the quality, efficiency and integrity of the Massachusetts Department of Transportation’s (“MassDOT”) operating and capital programs. As part of its statutory mandate, the ISAU seeks to prevent, detect and correct fraud, waste and abuse in the expenditure of public and private transportation funds. The ISAU is also responsible for examining and evaluating the adequacy and effectiveness of MassDOT’s operations, including its governance, risk-management practices and internal processes.

II. Massachusetts Department of Transportation

Created as part of Transportation Reform in 2009, MassDOT is responsible for managing the Commonwealth’s roadways and public transit systems, as well as licensing all Massachusetts drivers and vehicles. It is made up of four divisions: the Registry of Motor Vehicles (“RMV” or “Registry”), the Highway Division, the Aeronautics Division, and Rail and Transit.

The RMV is responsible for the administration of driver’s licenses, motor vehicle registrations and vehicle inspections across the state. Among its many other duties, the RMV reviews and approves applications for disability parking placards and disability license plates.

III. Obtaining a Disability Parking Placard

Massachusetts disability parking placard

A. Federal Guidelines

While state law governs parking accommodations for people with disabilities, the U.S. Department of Transportation has developed regulations to assist states to adopt uniform rules (the “Uniform System” or “guidelines”).5 Congress explained the purpose of the regulations as follows:

The purpose of this part is to provide guidelines to States for the establishment of a uniform system for handicapped parking for persons with disabilities to enhance access and the safety of persons with disabilities which limit or impair the ability to walk.6

The guidelines provide model definitions and rules regarding disability placards7, parking requirements, parking space design, and interstate reciprocity. The federal government encourages states to adopt these guidelines, but it does not require them to do so. The RMV relied, in part, on these guidelines to develop the requirements for obtaining a disability parking placard in Massachusetts.

Under the federal guidelines, only “persons with disabilities which impair or limit the ability to walk” would be eligible for a disability parking placard.8 The regulations define that phrase to mean individuals who:

- Cannot walk 200 feet without stopping to rest; or

- Cannot walk without the use of, or assistance from, a brace, cane, crutch, another person, prosthetic device, wheelchair, or other assistive device; or

- Are restricted by lung disease to such an extent that the person’s forced (respiratory) expiratory volume for one second, when measured by spirometry, is less than one liter, or the arterial oxygen tension is less than sixty mm/hg on room air at rest; or

- Use portable oxygen; or

- Have a cardiac condition to the extent that the person's functional limitations are classified in severity as Class III or Class IV according to standards set by the American Heart Association; or

- Are severely limited in their ability to walk due to an arthritic, neurological, or orthopedic condition.9

B. State Law

Like the federal guidelines, Massachusetts’ requirements for obtaining a disability parking placard primarily focus on conditions that limit an individual’s ability to walk.10

Consequently, the RMV may issue placards only to persons who need them to “minimize the distance to be traveled between the person’s parked vehicle and the ultimate destination, or to accommodate movement between the vehicle and a wheelchair or other assistive device.”11

Specifically, to qualify for a placard, an individual must meet one or more of the following medical standards:

- Cannot walk 200 feet without stopping to rest, or cannot walk without the assistance of another person, prosthetic aid, or other assistive device, as a result of a described clinical diagnosis;

- Has a cardiovascular disease to the extent that his or her functional limitations are classified in severity as Class III or Class IV by the American Heart Association;

- Has a pulmonary disease to the extent that forced expiratory volume (FEV-1) in one second when measured by spirometry is less than one liter, or requires continuous oxygen therapy, or has an oxygen saturation level of 88% at rest or with minimal exertion even with supplemental oxygen;

- Is blind to the extent that his or her central visual acuity does not exceed 20/200 (Snellen12) in the better eye, with corrective lenses, or has a visual acuity that is greater than 20/200 in the better eye but with a limitation in the field of vision such that the widest diameter of the visual field subtends an angle not greater than 20°. (The Snellen eye chart is used to measure visual acuity and consists of eleven lines of block letters that decrease in size);

- Has lost, or permanently lost the use of, one or more limbs.13

Placards allow the placard holder to park in designated handicapped spaces or at parking meters for free.14 Furthermore, the maximum time limit for parking at a meter (typically one or two hours) does not apply to a vehicle with a placard.15 Additionally, under 540 CMR 17.05(1), only the person named on the placard may use the placard. A driver who is transporting a placard holder to or from his destination may park in a meter or handicapped space; however, the meter or handicapped space cannot be more than ten minutes away from where the driver dropped off or picked up the placard holder.16 Lastly, no one may use a placard beyond its expiration date.17

C. The RMV's Application for a Disability Parking Placard

To receive a disability parking placard in Massachusetts, an individual must submit an application certifying his qualifying medical condition.18 A healthcare provider must complete and sign the application, list the individual’s clinical diagnosis, and determine whether the placard should be temporary or permanent.19 Further, the application contains a list of physical limitations and medical conditions, and healthcare providers are directed to “check all that apply” to the applicant.

Specifically, the application states:

___ Unable to walk 200 feet without assistance. List necessary ambulatory aids: __________

___ Legally Blind* (Cert. Of Blindness may substitute for professional certification) (*automatic loss of license)

___ Chronic Lung Disease (check at least one of the following criteria):

FEV1 test results___O2 saturation with minimal exertion___ (*automatic loss of license if O2 saturation < 88%)

Use of Portable Oxygen? Yes ___ No ___

Note: Asthma is not in and of itself a qualifying condition. Please describe degree and frequency of impairment (pulmonary test results required.)

___ Cardiovascular Disease

AHA Functional Classification (circle one): I II III IV* (*automatic loss of license)

___ Arthritis (please state type, severity, and location) ___________________

___ Loss of limb or permanent loss of use of a limb20

Currently, the average processing time for a placard application is four to six weeks.21 The Medical Affairs Bureau (“MAB” or the “Bureau”) is the division within the RMV that processes disability parking placards for the state. The MAB verifies that the provider who signed the application holds a valid medical license and rejects an application when the provider’s license is not current or active. The MAB can also ask for additional medical documentation, but only when “the medical certification contains insufficient information to enable the Registry reasonably to determine whether the medical qualifications have been satisfied.”22

On occasion, the MAB will reject an application with a vague diagnosis or request additional medical information to verify that an application contains the required medical criteria. Since the MAB does not employ medical personnel, however, it does not make determinations regarding medical diagnoses or question whether certain diagnoses warrant placards. Rather, the MAB approves most applications that are complete, meet the requirements on the application and have a valid provider signature.

In 2015, the MAB processed 53,996 new placard applications; of those, it rejected 8%.

| Year | Permanent Placards at Year End | Temporary Placards at Year End | Total Placards at Year End |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2011 | 338,984 | 16,790 | 355,774 |

| 2012 | 357,162 | 17,266 | 374,428 |

| 2013 | 374,819 | 17,283 | 392,102 |

| 2014 | 389,099 | 17,353 | 406,452 |

| 2015 | 399,312 | 18,760 | 418,072 |

Currently, the MAB does not require placard holders to return expired placards. Due to the volume of temporary and permanent placards in use, the MAB is not equipped to collect and dispose of all expired placards. Instead, the MAB instructs placard holders to destroy or dispose of expired placards themselves.

D. Lost or Stolen Placards

Individuals whose placards are lost or stolen may request a replacement placard from the MAB. Placard holders must submit a “Request for Replacement Placard Form” with a completed affidavit declaring the placard lost or stolen. 23 Once processed, the MAB issues the individual a new placard, which contains a new placard number. The MAB sends a copy of the replacement form to the placard holder’s local parking commission. The MAB also cancels the previous placard in the RMV’s database, thereby invalidating the prior placard number. However, cancelling a placard number in the RMV’s system does not prevent a holder from continuing to use the invalid placard itself. Finally, if a placard holder recovers a lost or stolen placard, he is required to return it to the MAB.

IV. Combatting Abuse

As previously discussed, placards allow persons with disabilities to park in designated handicapped spaces, as well as at parking meters for free, for an unlimited length of time. The prospect of free parking can incentivize individuals to misuse placards by, for instance, using another person’s placard to commute to and from work. This incentive is especially powerful in urban areas such as Boston, where parking in a garage can cost over $500 a month and buying a parking space can cost over $100,000.

A. Within Massachusetts

1. Civil and Criminal Penalties

It is illegal to use another person’s placard.24 It is also illegal to use a placard that has expired or been cancelled.25 State law also requires the placard holder to display the placard “so as to be readily visible through the windshield of the vehicle and in accordance with instructions provided by the registrar from time to time.”26 Any person who wrongfully displays or uses a placard or plate in violation of M.G.L. c. 90, § 2, is subject to a fine of $500 for a first offense, and $1,000 for every subsequent offense. The RMV will also suspend the operator’s license or his right to operate if he is found to have misused a placard; the suspension is thirty days for a first offense, ninety days for a second offense, and one year for every subsequent offense.27 Any placard holder who authorizes, permits, or allows his placard to be used by another person may have his placard revoked.28 In addition to these civil penalties, M.G.L. c. 90, § 24B, makes it a crime, punishable with a $500 fine and up to five years in jail, to falsely procure, steal, alter or counterfeit a placard. The statute also makes it a crime to possess or use a falsely procured, stolen, altered or counterfeit placard.29

2. The RMV

Since the OIG issued its 2013 report, the RMV has increased its efforts to combat placard abuse within the state. The RMV created and promoted a placard abuse hotline to encourage members of the public to report suspected abuse. The RMV redesigned placards to include a visible warning statement notifying holders of the penalties for misusing a placard. Additionally, the RMV created a joint task force dedicated to addressing and resolving issues surrounding placard abuse. The task force is comprised of representatives from the RMV, the Massachusetts Office on Disability, the State Police, the city of Boston’s Office of the Parking Clerk, the Boston Commission for Persons with Disabilities, the Boston Police Department, the Burlington Police Department, the Massachusetts Executive Office of Elder Affairs and the Office of the Inspector General. The task force is committed to increasing enforcement of the current law, amending state law to increase the penalties for placard abuse, and tightening administrative controls to prevent and detect abuse more effectively.

Finally, the RMV’s Medical Affairs Bureau frequently receives reports of placard abuse; however, it does not have the authority to investigate placard abuse or enforce placard laws. Instead, the MAB must rely on local law enforcement departments to investigate and resolve placard abuse complaints. Consequently, the MAB refers complaints to various local police departments to enforce placard laws. Moreover, the Bureau has a staff of only seven full-time and two part-time employees who process over 100,000 placards a year,30 in addition to their other duties.31 Thus, it does not have the capacity to scrutinize placard applications, follow up with medical professionals or analyze placard applications for potential misuse.

3. Cities and Towns

Law enforcement officials can issue civil citations for misusing a placard in violation of M.G.L. c. 90, § 2, as well as parking tickets for improperly using a placard. Pursuant to M.G.L. c. 40, § 8J, moreover, Massachusetts cities and towns may establish a commission on disability to benefit the disabled within their communities. Cities and towns that accept the provisions of Section 8J can receive the fines assessed for violating disability parking rules – including fines from parking tickets – and allocate those funds to their commission on disabilities.32

Waltham, Fall River and Burlington have adopted Section 8J and have implemented enforcement programs to reduce placard abuse. The Waltham Disability Services Commission created a placard abuse task force in 2006, following receipt of a $10,000 grant. The operation of the task force involves regular surveillance of targeted areas by two officers as well as managing a placard abuse hotline.

Since its inception, the task force has generated nearly $1,000,000 in revenue from placard citations and parking tickets. Waltham provides revenue from parking tickets directly to the Waltham Disability Services Commission, which uses the funds to sustain the task force and develop community projects. The commission has used these funds for projects such as building a disability accessible children’s playground, creating a scholarship fund for disabled children and creating disability accessible entryways throughout Waltham.

Fall River also has a self-funded placard program, and has issued approximately 4,300 parking tickets since 2012. Fall River’s designated officers target handicapped parking spaces at retail centers. On average, Fall River issues 150 parking tickets a month, generating average monthly revenues of $9,500. The additional revenue allows the Fall River Commission on Disability to air public service announcements about placard fraud on radio and local television stations. The commission also runs placard abuse education programs at local senior centers.

In Burlington, police have partnered with the Burlington Disability Access Commission to ensure drivers obey the laws when in parking lots and on the streets. Law enforcement officials issue civil citations and parking tickets to those who are caught improperly using a placard or who are in a handicapped parking spot illegally. These drivers may also lose their licenses and could have their vehicles towed. Burlington’s commission also pays for detail officers to conduct targeted enforcement in retail areas. In 2015, Burlington police issued 174 parking tickets for placard misuse.

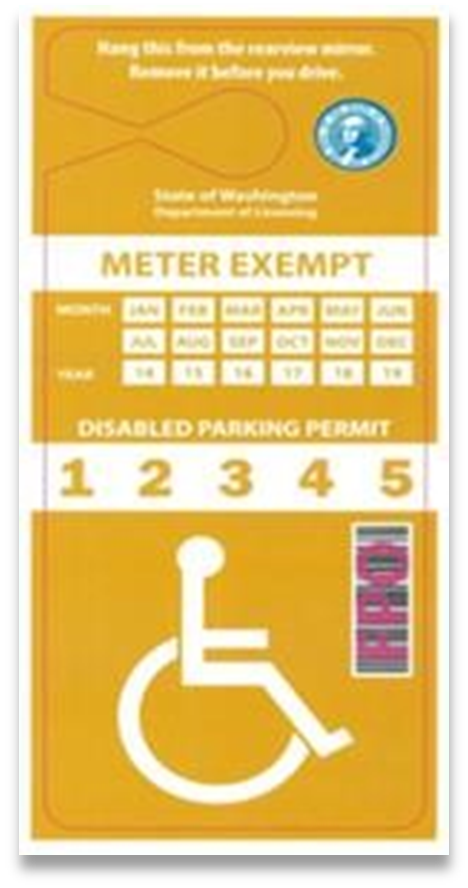

Washington state meter-exempt parking placard

B. Placard Reforms outside Massachusetts

Cities and states across the country have changed their approach to disability parking placards based on ongoing abuse, particularly in downtown metropolitan areas. Because free parking is a strong incentive for misusing a placard, many of these changes have focused on the meter-fee exemption. For example, the state of Michigan adopted a “two-tier” system in 1995, which places placard holders into two groups: (1) those who are severely disabled and cannot operate or reach a parking meter; and (2) all other applicants.33 Only severely disabled individuals qualify for a meter-fee exemption. All other placard holders may still park in handicapped parking spaces, but they must pay to park at a parking meter. After implementing this two-tier system, only 2% of previous placard holders qualified for the meter-fee exemption.

Portland, Oregon also eliminated the meter-fee exemption for vehicles with placards on July 1, 2014.34 After making this change, the number of vehicles with placards that occupied metered parking spaces decreased by 70%.35 The state of Illinois adopted a two-tier system in 2014 after the vendor operating Chicago’s parking meters determined that the meter-fee exemption cost $54.9 million over two years, which the city had to pay the vendor. Illinois’ two-tier system is similar to Michigan’s.36 Furthermore, temporary placard holders are not eligible for Illinois’ meter-fee exemption. According to the Illinois Secretary of State, only 10% of the nearly 300,000 placard holders qualified for the meter-fee exemption, based on the two-tier system.

Finally, to obtain a disability parking permit in New York City, an applicant must (1) require the use of a non-commercial passenger vehicle for transportation; and (2) have a severe, permanent disability that impairs mobility as certified by both his personal physician and a New York City physician designated by the Department of Health and Mental Hygiene (DOHMH).37 In addition, the DOHMH may require certain applicants to also have an in-person medical evaluation. The city only accepts its disability parking permits at metered spaces, designated disabled spaces and no-parking zones. New York state placards and other state placards are not valid on New York City streets.38

Additional Resources

Contact for Abuse of Disability Placards in Massachusetts: Background

Online

Phone

Address

| Date published: | February 24, 2016 |

|---|