- Scientific name: Utterbackiana implicata

- Species of Greatest Conservation Need (MA State Wildlife Action Plan)

Description

Alewife floater

Alewife floater (Anodonta implicata Say, 1829) is a medium- to large-bodied mussel that can exceed 15 cm (6 in) in length. Shells are elongate and either ovate or elliptical in shape and are laterally inflated. The beaks are prominently raised above the hinge line, which is straight or slightly curved. The shells are thin but have a distinct thickening from the anterior to posterior end that is even more pronounced in larger individuals. The nacre is typically copper, pale pink, or white. The periostracum is smooth and may vary in color from green to straw yellow, brown, or black depending on age, location and environmental conditions. The periostracum of younger animals may contain rays. Shells lack pseudocardinal and hinge teeth (Smith 1991, Nedeau 2008).

Alewife floater can be difficult to distinguish from the more widespread and co-occurring eastern floater (Pyganodon cataracta). The thinner shell on the anterior-ventral end, combined with a more pronounced dorso-posterior wing and less elliptical overall shape can help distinguish between these species. Sometimes this species can also be mistaken for larger individuals of the Massachusetts Special Concern creeper (Strophitus undulatus), particularly in stream environments. Creeper tend be more subovate to subtrapezoidal with less sculpturing around the beak. An expert should be consulted for accurate identification.

Life cycle and behavior

Alewife floaters are essentially sedentary filter feeders that spend most of their lives partially burrowed into the bottoms of rivers, streams, lakes, and ponds. alewife floater, like all freshwater mussels, have larvae (called glochidia) that must attach to the gills or fins of a vertebrate host to develop into juveniles. Reproduction occurs in August and glochidia are released the following spring (NatureServe 2014). Glochidia are triangular and possess stout hooks that aid in attachment to gill and fin tissue of fish hosts (Nedeau 2008). Reported hosts include alewife (Alosa pseudoharengus), blueback herring (Alosa aestivalis), white sucker (Catostomus commersoni), threespine stickleback (Gasterosteus aculeatus), pumpkinseed (Lepomis gibbosus), white perch (Morone americana), and striped bass (Morone saxatilis). However, rates of metamorphosis have not been reported for many of these species (Kneeland and Rhymer 2008, Nedeau 2008).

Distribution and abundance

Shell midden composed mainly of alewife floater along the Merrimack River.

Alewife floater is an Atlantic-slope endemic species, ranging from the Pee Dee River in North Carolina to the coastal plains of Quebec and Nova Scotia. Though often locally abundant, the species’ range is largely restricted to waterbodies without barriers to the Atlantic coast, or those with suitable fish passage structures.

In Massachusetts, the alewife floater occurs in the Westfield, Middle Connecticut, Nashua, Charles, Taunton, and Cape Cod watersheds. The species also likely occurs in the mainstem Merrimack River, as evidenced by middens mostly composed of alewife floater. Live individuals have not been recorded because of limited survey effort. Alewife floater is often found in relatively low abundances.

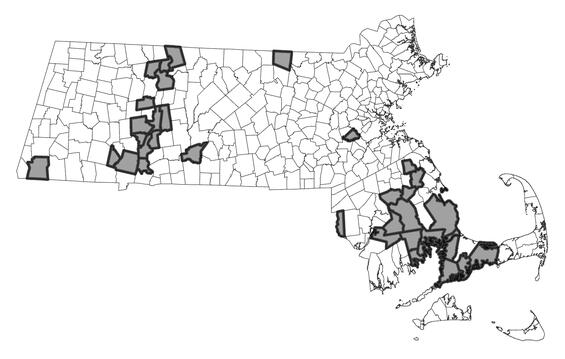

Distribution in Massachusetts.

1999-2024

Based on records in the Natural Heritage Database.

Habitat

Alewife floaters occupy various substrate types in rivers, streams and lakes, and abundances may be closely tied to host fish habitat. Alewife floater have been reported from both slow-moving depositional riverine habitats among aquatic vegetation (Nedeau 2008), and those with relatively high velocities with substrates of gravel, cobble, boulder and bedrock (Nedeau 2012). In lacustrine environments, they have been found in the littoral zone exposed to considerable wave action, as well as sandy and muddy pools at depths greater than 30 feet (Nedeau 2008).

Healthy habitats are vital for supporting native wildlife and plants. Explore habitats and learn about conservation and restoration in Massachusetts.

Big river habitat typical of alewife floater.

Threats

Exposed riverbed as a result of regulated streamflows.

Because alewife floaters are essentially sedentary filter feeders, they are unable to flee from degraded environments and are vulnerable to the alterations of water bodies. Alewife floater occurs in lakes and rivers, and the threats in these two habitats differ. Overlapping threats include nutrient enrichment, sedimentation, other forms of pollution, non-native and invasive species, and the many consequences of urbanization. River populations of alewife floater are threatened by alteration of natural flow regimes, encroachment of river corridors by development, habitat fragmentation caused by dams, and a legacy of land use that has greatly altered the natural dynamics of river corridors (Nedeau 2008). Lake populations are challenged by intense development, modification and recreational use of sensitive shoreline habitats, accelerated eutrophication, water level manipulation, and more frequent cyanobacteria blooms. Invasive plants and animals, such as European milfoil and basket clam (Corbicula fluminea), are having severe impacts on the fragile ecology of coastal plain ponds. The ultimate consequences on alewife floater and other native species are not completely known, but the prognosis is bleak. In addition, the long-term effects of regional or global problems such as acidic precipitation, mercury contamination, and climate change are considered severe but little empirical data relates these stressors to mussel populations. In combination with the above stressors (e.g., water withdrawals, eutrophication), effects from climate change, including sustained droughts and warmer water temperatures, threaten alewife floater populations by reducing water levels, and creating more suitable conditions for cyanobacteria blooms, particularly in lentic systems where these have caused mussel kills.

Likely the highest risk to alewife floater is the loss of fish hosts. Though many host species have been reported, there are limited data on metamorphosis rates and determination of the primary hosts used in Massachusetts. River herring, blueback herring (Alosa aestivalis) and alewife (Alosa pseudoharengus), are thought to be the primary hosts used in New England. Both fish species are commercially important and have been undergoing reductions in population growth throughout their range. Continued loss of river herring stocks could affect alewife floater population persistence if other suitable hosts are not recognized. Alternatively, restoration of habitat and passage for river herring and other anadromous host species could result in the expansion of alewife floater to recolonize historic distributions (Smith 1985, Raithel and Hartenstine 2006).

Conservation

Survey and monitoring

Standardized surveys are critically needed to monitor known populations, evaluate habitat, locate new populations, and assess population viability at various spatial scales (e.g., stream, watershed, state). Survey efforts should continue to search for new populations, particularly in coastal watersheds, and expand our knowledge on species distribution in extant watersheds every 5 years or to the extent feasible. Establishment of long-term monitoring sites in extant watersheds is needed to acquire critical demographic and population trend data where this species overlaps with state-listed mussel species. Monitoring these sites should occur annually in multi-year blocks or as needed.

Management

Discovery and protection of viable mussel populations is critical for the long-term conservation of freshwater mussels. Currently, much of the available mussel occurrence data are the result of limited presence/absence surveys. Coastal plain ponds and large coastal rivers are critical to the long-term viability of alewife floater in Massachusetts, and these habitats are also experiencing intense development pressure and recreational use. Understanding this threat and developing conservation and management strategies is a high priority for NHESP. Other conservation and management recommendations include: understand the effects of shoreline development and recreational use of lakeshores; maintain naturally variable river flows and lake water levels and limit water withdrawals; identify, mitigate, or eliminate sources of pollution, including excess nutrients, to water bodies; identify dispersal barriers for host fish, especially those that fragment the species range within a river or watershed, and seek options to improve fish passage or remove the barrier; maintain adequate vegetated riparian buffers along rivers and lakes; protect or acquire land at high priority sites.

Research needs

A better understanding of host fish relationships is needed; this information might help guide fisheries management at fishways. Habitat mapping of large rivers can aid in evaluation of suitable physical habitat and direct future survey effort. Climate change projections for water temperature and water levels in occupied and potential watersheds for species introduction are also needed to assess current and future population risks to drought and cyanobacteria blooms and identify potential refuges. Investigation of impacts of invasive species, particularly basket clam (Corbicula fluminea), on alewife floater is needed.

Acknowledgements

MassWildlife thanks Peter Hazelton for providing significant support to this document.

References

Nedeau, E.J. 2008. Freshwater Mussels and the Connecticut River Watershed. Connecticut River Watershed Council, Greenfield, Massachusetts. xviii + 132pp.

Nedeau, E.J. 2012. Freshwater Mussel Survey in the Connecticut River for the Turners Falls and Northfield Mountain Hydroelectric Projects: FERC PROJECT #1889, 2485. Report prepared for FirstLight Power Resources. Biodrawversity, Amherst, Massachusetts. 12pp.

Raithel, C.J., and R.H. Hartenstine. 2006. The status of freshwater mussels in Rhode Island. Northeastern Naturalist 13: 103-116.

Smith, D.G. 1985. Recent range expansion of the freshwater mussel Anodonta implicata and its relationship to clupeid fish restoration in the Connecticut River system. Freshwater Invertebrate Biology 4(2): 105-108.

Smith, D.G. 1991. Keys to the Freshwater Macroinvertebrates of Massachusetts: including the Porifera, Colonial Cnidaria, Entoprocta, Ectoprocta, Platyhelminthes, Nematophora, Nemertea, Mollusca (Mesogastropoda And Pelecypoda), and Crustacean (Branchiopoda and Malacostraca). Department of Zoology, University of Massachusetts, Amherst, Massachusetts. 236pp.

Contact

| Date published: | March 31, 2025 |

|---|