- Scientific name: Falco sparverius

- Species of Greatest Conservation Need (MA State Wildlife Action Plan)

Description

The American kestrel, formerly known as the sparrow hawk, is North America’s smallest and most colorful falcon. This species is sexually dimorphic with the smaller male having slaty-blue wings and rufous tail with a single, large subterminal black band, while the female has rufous wings and tail with thin black barring. As with other falcons, kestrels have long, pointed wings enabling acrobatic flight. It inhabits open areas where it hunts from perches or hovers above the landscape, focusing on arthropods and small mammals on the ground and insects and small birds on the wing. The American kestrel is a secondary cavity nester that readily accepts artificial nest boxes.

American kestrel

Life cycle and behavior

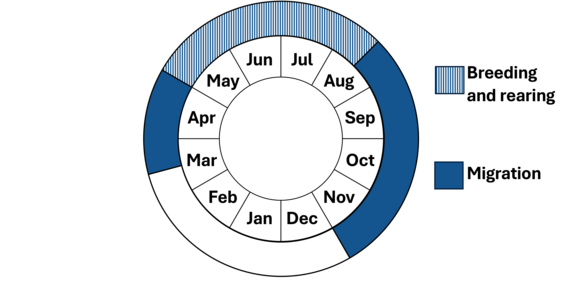

Although some of the nesting kestrels in Massachusetts may stay in the region all year if food resources allow, most are migratory and spend the winter in the southeastern states. There are several kestrels that nest in Massachusetts wintering in Florida. They are an early spring migrant with most birds arriving and moving through Massachusetts in late March and April. Nesting begins soon after arrival and once a cavity is selected. Natural nest sites are tree cavities and artificial nest sites include boxes and occasionally holes in buildings. The typical clutch size is 4-5 eggs, which are incubated for approximately 28 days, and chicks fledge from the nest between 28-31 days following hatching. Fledglings continue to be fed by adults for around two weeks after leaving the nest and until they gain independence. Kestrels may begin migrating south in late July and August, but the majority of migrants move through Massachusetts in September.

Figure 1. Phenology in Massachusetts. This is a simplification of the annual life cycle. Timing exhibited by individuals in a population varies, so adjacent life stages generally overlap each other at their starts and ends.

Population status

Breeding Bird Survey data shows that the population of the American kestrel has experienced an overall decline of 1.4 percent annually from 1966 to 2022. Of the states with kestrel declines, Massachusetts ranks as having one of the sharpest declines during that timeframe, at 4.7 percent annually. Similar declines are found throughout New England. This recent decline follows the probable population surge of the 18th and 19th centuries when large areas of eastern North America were deforested for agricultural purposes that would have benefitted the species.

Distribution and abundance

The American kestrel is the most widespread falcon in North America occurring from Alaska to Canada’s Maritime Provinces, and south through Central America. The American kestrel breeds in all regions of Massachusetts with open country, though specific breeding sites can be limited by suitable nesting cavities. The highest densities of kestrels in the state can be found along the Connecticut River Valley.

Adult American kestrel in flight

Habitat

The American kestrel uses a variety of open to semi-open habitats, including meadows, wetlands, grasslands, old-field successional communities, open parkland, and agricultural fields, as well as urban and suburban areas. Regardless of vegetative composition, breeding territories are characterized by either large or small patches covered by short ground vegetation, with taller woody vegetation either sparsely interspersed upon the landscape or altogether absent. Suitable nest trees and perches are required for breeding territories, and with the introduction of nest boxes, previously unused but otherwise suitable habitat is now being occupied. Because of the relatively large territory size of the American kestrel, there are few discrete sites that hold a significantly high percentage of the Massachusetts population.

Healthy habitats are vital for supporting native wildlife and plants. Explore habitats and learn about conservation and restoration in Massachusetts.

Threats

American kestrel chicks

The lack of suitable nesting cavities appears to be a limiting factor for this species in Massachusetts. Additionally, an overall decrease in suitable open habitat due to development or forest succession has reduced the presence and breeding success of the species in the state. American kestrel also has been proven sensitive to pesticides and other toxins, resulting in documented cases of reduced reproductive success and direct adult mortality. The increase in nesting Cooper’s hawks is another threat to kestrels as they can directly prey upon the smaller kestrel, especially recently fledged birds that are inexperienced flyers.

Rodenticides (e.g., Second Generation Anticoagulant Rodenticides - SGARs) move up food chains and pose a threat to raptors when they consume prey that have ingested these chemicals. As a result, SGARs have been found in a high percentage of raptors that have been tested for them in Massachusetts, and it is well documented that they can kill individual raptors. However, their population-level impacts on raptors remain largely unknown.

Conservation

Perhaps the easiest way to improve American kestrel habitat is to continue the placement of nest boxes in suitable landscapes. To encourage this, MassWildlife has been providing outreach materials on kestrel conservation to the public and working with conservation partners and landowners to distribute kestrel nest box plans and deploy boxes. Additionally, the use of ecological management techniques such as mechanical vegetation removal or prescribed fire to promote and maintain open habitats should be encouraged. Where suitable habitat currently exists, efforts should be made to protect the landscape from development. Over the last several years, MassWildlife has been deploying tracking transmitters on kestrels to collect data on their annual movements and survival to help guide conservation efforts.

Conduct research to better understand the impacts of highly toxic rodenticides (e.g., SGARs) to raptor populations. Promote an integrated pest management approach that emphasizes the use of alternative pest control measures whenever possible to reduce negative impacts to wildlife. Coordinate with other state agencies to improve tracking and reporting of rodenticides found in wildlife and develop outreach materials for the public.

References

Sauer, J.R., J.E. Hines, and J. Fallon. 2022. The North American Breeding Bird Survey, Results and Analysis 1966 - 2022. Version 2004.1. USGS Patuxent Wildlife Research Center, Laurel, Maryland.

Smallwood, J. A. and D. M. Bird (2020). American Kestrel (Falco sparverius), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (A. F. Poole and F. B. Gill, Editors). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA.

Veit, R., and W.R. Petersen. 1993. Birds of Massachusetts. Massachusetts Audubon Society, Lincoln, Massachusetts.

Contact

| Date published: | April 28, 2025 |

|---|