Overview

The Executive Office of the Trial Court (EOTC) was established in 1978 to help with coordination of and communication between the various entities that comprise the Commonwealth’s court system.1 This system includes, but is not limited to, seven state-level Trial Court departments,2 the Office of Jury Commissioner, the Massachusetts Probation Service, and the Office of Court Management.

According to the Massachusetts Trial Court Strategic Plan 2023–2025, EOTC’s mission statement is as follows:

The Trial Court is committed to:

- Fair, impartial, and timely administration of justice;

- Protection of constitutional and statutory rights and liberties;

- Equal access to justice for all in a safe and dignified environment strengthened by diversity, equity, and inclusion;

- Excellence in the adjudication of cases and resolution of disputes;

- Courteous service to the public by dedicated professionals who inspire public trust and confidence.

Currently, EOTC comprises the following nine divisions: the seven Trial Court departments previously referenced, as well as the Massachusetts Probation Service and the Office of Jury Commissioner. The following is a sample of audits that the Office of the State Auditor has completed during the last few years of EOTC and its divisions.

- EOTC, issued in 2021;

- the Juvenile Court Department, issued in 2022;

- the Land Court Department, issued in 2022; and

- the Office of Jury Commissioner, issued in 2024.

Additionally, the court administrator oversees the Office of Court Management, which, according to the Massachusetts Trial Court Strategic Plan 2023–2025, oversees many matters, such as those related to capital planning, human resources, information technology (IT), language access, law libraries, security, and workplace rights. In fiscal years 2023 and 2024, EOTC received appropriations of $861,538,815 and $887,242,797, respectively. During at least one point in fiscal year 2024, EOTC was staffed by 371 judges.

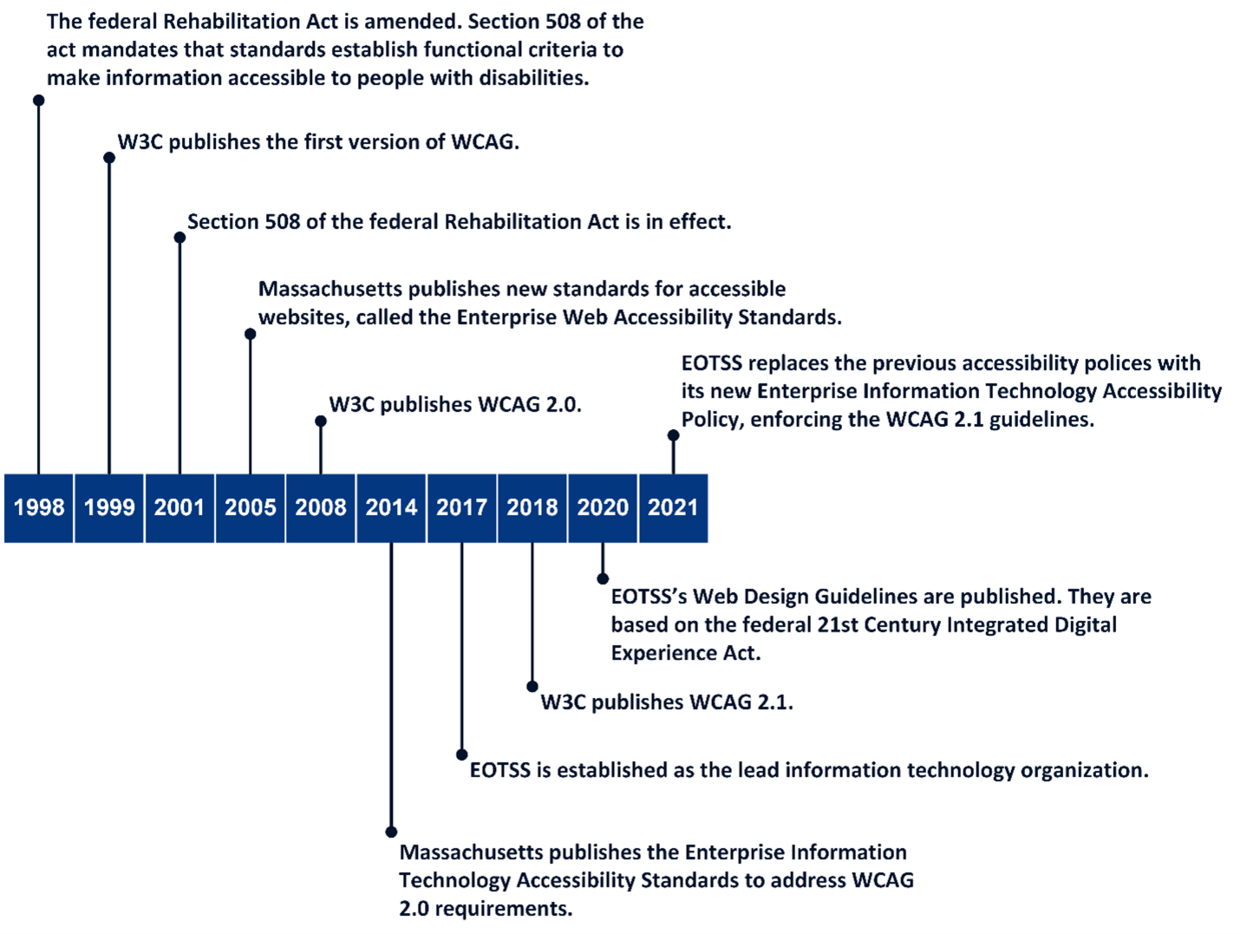

Massachusetts Requirements for Accessible Websites

In 1999, the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C), an international nongovernmental organization responsible for internet standards, published the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) 1.0 to provide guidance on how to make web content more accessible to people with disabilities.

In 2005, the Massachusetts Office of Information Technology,3 with the participation of state government webpage developers, including developers with disabilities, created the Enterprise Web Accessibility Standards. These standards required all executive branch state agencies4 to follow the guidelines in Section 508 of the Rehabilitation Act amendments of 1998. These amendments went into effect in 2001 and established precise technical requirements to which electronic and IT products must adhere. This technology includes, but is not limited to, products such as software, websites, multimedia products, and certain physical products, such as standalone terminals.

In 2008, W3C published WCAG 2.0. In 2014, the Massachusetts Office of Information Technology added a reference to WCAG 2.0 in its Enterprise Information Technology Accessibility Standards.

In 2017, the Executive Office of Technology Services and Security (EOTSS) was designated as the Commonwealth’s lead IT organization for the executive branch state agencies. EOTSS is responsible for the development and maintenance of the Enterprise Information Technology Accessibility Standards5 and the implementation of state and federal laws and regulations relating to accessibility. As the principal executive agency responsible for coordinating the Commonwealth’s IT accessibility compliance efforts, EOTSS supervises executive branch state agencies in their efforts to meet the Commonwealth’s accessibility requirements.

In 2018, W3C published WCAG 2.1, which built on WCAG 2.0 to improve web accessibility on mobile devices and to further improve web accessibility for people with visual impairments and cognitive disabilities. EOTSS published the Enterprise Information Technology Accessibility Policy in 2021 to meet Levels A and AA of WCAG 2.1.

Timeline of the Adoption of Website Accessibility Standards by the

Federal Government and Massachusetts

Executive branch state agencies must comply with EOTSS’s policies and standards. However, non-executive branch state agencies, such as EOTC, must also comply with EOTSS’s accessibility policies and standards when using an EOTSS web domain,6 as established by EOTSS’s Website Domain Policy. Part of this policy states that any government organization using an EOTSS web domain must comply with EOTSS’s Web Design Guidelines, which were published in 2020 and were based on the federal 21st Century Integrated Digital Experience Act. This law helps state government agencies evaluate their design and implementation decisions to meet state accessibility requirements.

Web Accessibility

Government websites are an important way for the general public to access government information and services. Deloitte’s7 2023 Digital Citizen Survey found that 55% of respondents preferred to interact with their state government services through a website instead of face-to-face interaction or a call center. Commonwealth of Massachusetts websites have millions of webpage views each month.

However, people do not interact with the internet uniformly. The federal government and nongovernmental organizations have established web accessibility standards intended to make websites more accessible to people with disabilities such as visual impairments, hearing impairments, and others. The impact of these standards can be significant, as the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that 1,488,012 adults (26% of the adult population) in Massachusetts have a disability, as of 2022.8 Among the estimated 26% of the adult population, 14% reported having serious difficulty with cognition, 10% reported having serious difficulty with mobility, 6% reported having deafness or serious difficulty hearing, and 5% reported having blindness or serious difficulty seeing (even when wearing glasses).9 Examples of web accessibility measures include, but are not limited to, having captioning on videos to help people with difficulty hearing understand the contents of the video; having form fields describe what data needs to be inputted into them to help people who have cognitive difficulties; and ensuring that people can interact with a webpage using keyboard commands alone to help people who have difficulty with mobility.

How People with Disabilities Use the Web

According to W3C, people with disabilities use assistive technologies and adaptive strategies specific to their needs to navigate web content. Examples of assistive technologies include screen readers, which read webpages aloud for people who cannot read text; screen magnifiers for individuals with low vision; and voice recognition software for people who cannot (or do not) use a keyboard or mouse. Adaptive strategies refer to techniques that people with disabilities employ to enhance their web interaction.10 These strategies might involve increasing text size, adjusting mouse speed, or enabling captions.

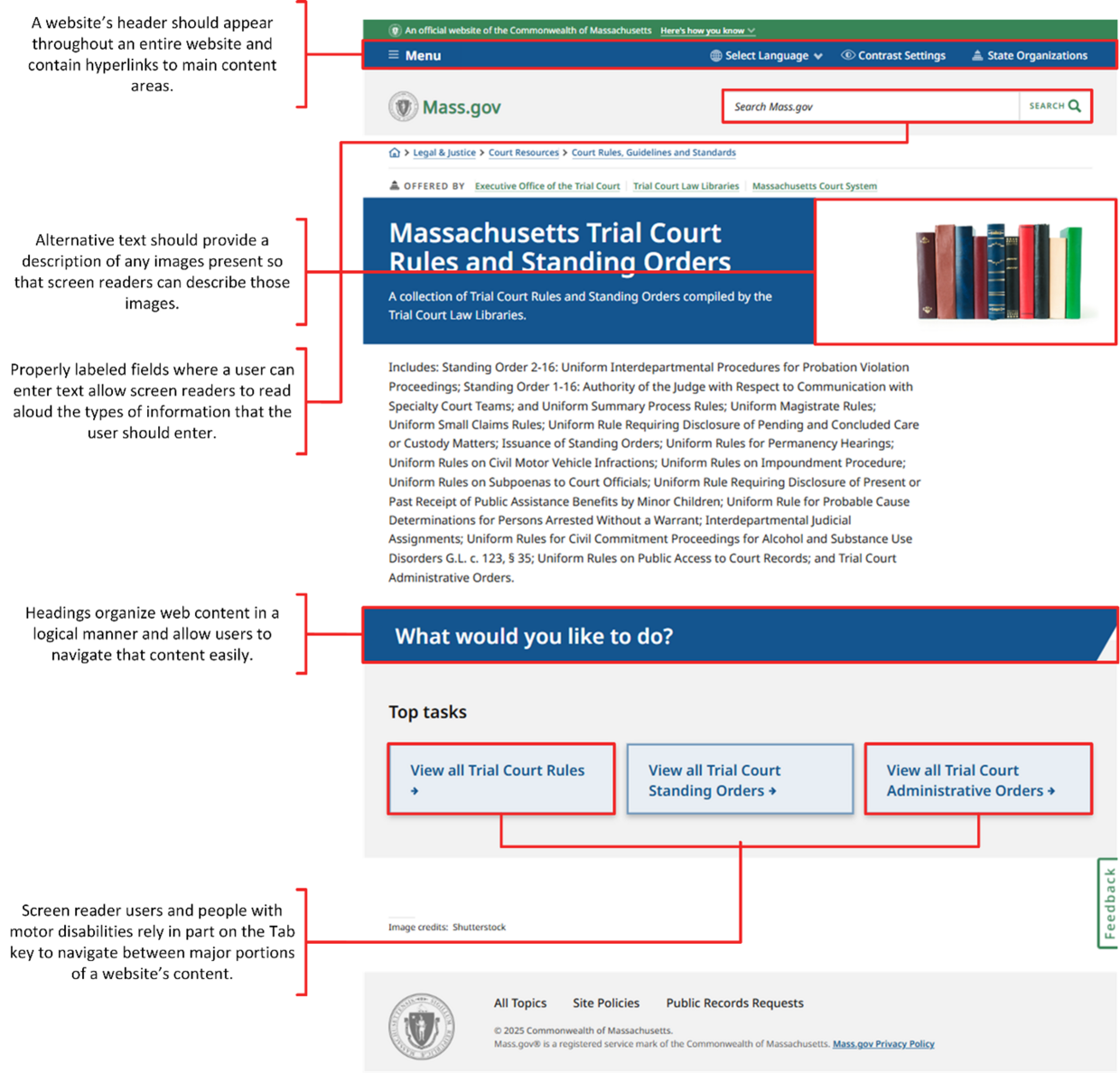

To make web content accessible to people with disabilities, developers must ensure that various components of web development and interaction work together. This includes text, images, and structural code; users’ browsers and media players; and various assistive technologies.

Accessibility Features of a Website11

| Date published: | August 6, 2025 |

|---|