- Scientific name: Eleocharis rostellata (Torr.) Torr.

- Synonymns: Scirpus rostellatus Torr.

- Species of Greatest Conservation Need (MA State Wildlife Action Plan)

Description

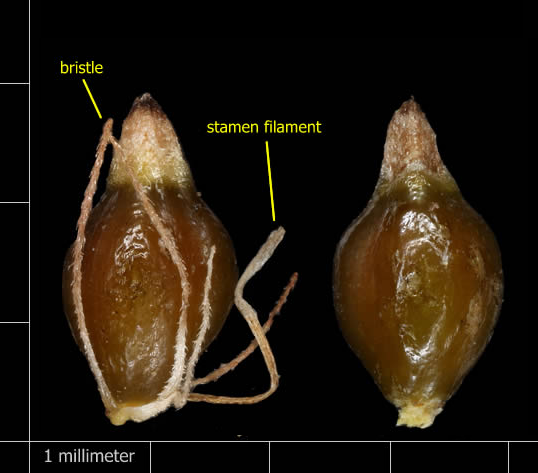

Achenes. Photo credit: Peter M. Dziuk, MinnesotaWildflowers.info

Beaked spikesedge, Eleocharis rostellata, is rare in New England. It grows in salt marshes that have some freshwater influence. The plants grow in clumps of long, tubular stems up to 2 mm (0.08 in) wide. The clumps form mats, sometimes so dense as to exclude other species.

The stems are typically 30-60 cm (1-2 ft) tall but can range from 20-100 cm (8-40 in). These stems are erect to ascending and may arch over and take root when longer.

Fruiting stems have a single spikelet 5-17 mm (0.2-0.7 in) long at the tip that’s only slightly wider than the stem. The achenes (seeds) are dark brown and shiny, 1.5-2.5 mm (0.06-0.1 in) tall and 1-1.2 mm (0.04-0.05 in) wide. On most species of Eleocharis, the tubercle at the top of the achene is obviously distinct due to its different shape and texture, and there is clear delineation between the achene body and the tubercle. However, the tubercles of E. rostellata are usually not distinct. Instead, they appear as an extension of the achene tapering to an acute point that’s lighter in color than the rest of the achene. Mature fruit can be found from early July to late August.

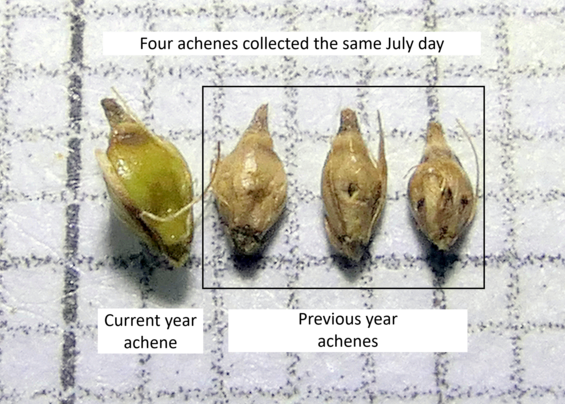

Achenes of different ages. Photo credit: Douglas E. McGrady

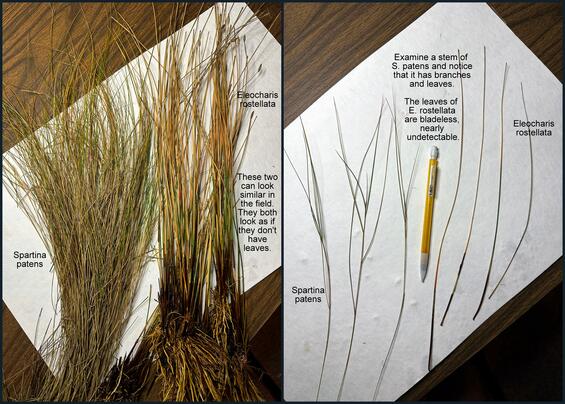

Eleocharis rostellata compared to Spartina patens. Photo credit: Douglas E. McGrady

Life cycle and behavior

The plants flower in spring and early summer, fruiting in late summer through early autumn. It is wind-pollinated. It can also reproduce vegetatively when extra-long venturesome stems arch over and root at the tip. This is a key trait to look for as there is no other species of Eleocharis in Massachusetts salt marshes that has this characteristic. Walking through a patch will break stems. Black-fruited spikesedge, E. melanocarpa, has this same trait, but is restricted to fresh water, typically in coastal plain ponds.

Two other species in our area have similar achenes: salt-pond spikesedge, E. parvula, grows in saline conditions, but it’s a tiny plant under typically under 10 cm (4 in) in height; few-flowered spikesedge, E. quinqueflora, grows in high pH freshwater conditions.

Fruiting stems can be scarce. Some plants growing in mats (patches) will produce none. Other patches of mats can have fruiting stems, but without viable achenes; the spikelets containing only rotted or aborted seeds, and these frequently include a tiny grub living in the spikelet.

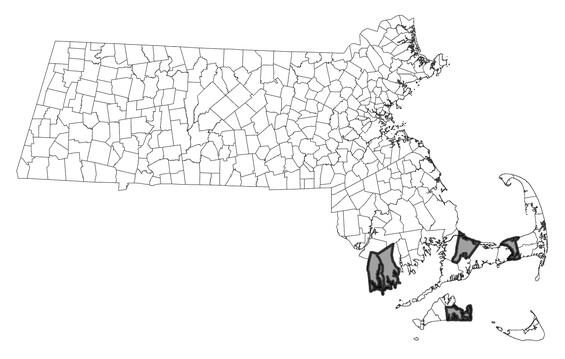

Photo credit: Douglas E. McGrady

Population status

Beaked spikesedge has recently been listed as a species of greatest conservation need (SGCN) and is maintained on the Massachusetts plant watch list. There are currently 7 known occurrences in the state verified since 1999 found in Barnstable, Bristol Dukes, and Plymouth Counties. There are 8 historical occurrences which have specific locational information in the above 4 counties and in Nantucket County.

Distribution in Massachusetts

1999-2024

Based on records in the Natural Heritage Database

Distribution and abundance

Beaked spikesedge is found across North America despite being restricted to brackish marshes along the coast in New England. Its range extends from Nova Scotia, Ontario and British Columbia south to Florida and California and into Mexico, with disjunct native populations in Argentina, Cuba, Dominican Republic and Bermuda (POWO 2025) growing in wetlands that are either brackish or have high pH. In New England, it is considered critically imperiled in Maine and Rhode Island, imperiled in Massachusetts, and is not ranked in Connecticut. The species does not occur in either New Hampshire or Vermont. Several other US states consider it imperiled or critically imperiled (NatureServe 2025).

Habitat

In New England, beaked spikesedge is typically found in the high salt marsh with other graminoids such as salt-meadow grass (Spartina patens), saltwater cord-grass (Spartina alterniflora), and saltmarsh spike-grass (Distichlis spicata). Beaked spikesedge, E. rostellata, typically stands taller than these species. Saltwater cord-grass and saltmarsh spike-grassshould not be confused with an Eleocharis: they both have flat leaves and a large inflorescence, compared to minimal leaves and a small terminal inflorescence on beaked spikesedge. From a distance, salt-meadow grass can resemble an Eleocharis. It can form large mats of what appear to be long, tubular stems. However, if one examines one plant, it is apparent that the stems have branches. Eleocharis stemsdo not have branches. When salinity is lower other species may be included such as common three-square bulrush, (Schoenoplectus pungens), twig-sedge (Cladium mariscoides), saltmarsh bulrush (Bolboschoenus robustus), and switchgrass (Panicum virgatum). When these species are present in the saltmarsh, it is more difficult to spot thebeaked spikesedge.

Healthy habitats are vital for supporting native wildlife and plants. Explore habitats and learn about conservation and restoration in Massachusetts.

Image by Doug McGrady.

Threats

The primary threat to beaked spikesedge is purple marsh crab (Sesarma reticulatum) herbivory and burrowing, destroying large areas of salt marsh, the beaked spikesedge’s habitat (Patterson et al. 2025, Smith 2024). Sea level rise due to climate change (Staudinger et al. 2024) also threatens the salt marshes where beaked spikesedge occurs and may cause permanent damage to the salt marsh where this species occurs.

Conservation

Survey and monitoring

Beaked spikesedge should be surveyed on a regular basis to track population health and size. The locations where this species has been observed historically should be resurveyed to update whether the species still occurs in those locations. This would also provide a good assessment of any changes in the habitat. De novo surveys should be completed in saltmarshes along tidal rivers and those with headlands that might seep ground water. The best time to survey this species is during the summer and into the fall.

Management

The primary management for beaked spikesedge is to protect its populations from anthropogenic activities. Salt marshes can be fragile environments and accidental damage can occur to these populations.

Research needs

Evaluate the quantity and quality of the seed to determine if collected seed is viable. Consider introducing plants from other nearby populations in Massachusetts to enhance the genetics of the existing plants and improve seed viability. The saltmarsh sparrow (Ammospiza caudacuta) favors the same habitat, so conservation of one species may serve the other as well.

Acknowledgements

MassWildlife acknowledges the expertise of Douglas E. McGrady, who contributed substantially to the development of this fact sheet.

References

Consortium of Northeastern Herbaria. 2025. Herbarium records. https://portal.neherbaria.org/portal/collections/list.php. Accessed 3/21/2025.

Gleason, Henry A., and Arthur Cronquist. Manual of Vascular Plants of Northeastern United States and Adjacent Canada, Second Edition. Bronx, NY: The New York Botanical Garden, 1991.

Jenkins, Jerry. Sedges of the Northern Forest, A Digital Atlas, Version 1.3, 21 February 2019: 288, 292.

Minnesota Wildflowers. 2006-2025. Taxonomy, descriptions, photos. https://www.minnesotawildflowers.info/grass-sedge-rush/beaked-spikerush. Accessed 3/21/2025.

NatureServe. 2025. NatureServe Network Biodiversity Location Data accessed through NatureServe Explorer [web application]. NatureServe, Arlington, Virginia. Available https://explorer.natureserve.org/. Accessed: 3/28/2025.

Patterson, Alex, Sara Grady, and Jeff King. “Developing Nature-based Solutions to Improve the Resilience of a Wellfleet Harbor Salt Marsh,” Presentation at Cape Cod Natural History Conference 2025.

POWO (2025). Plants of the World Online. Facilitated by the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Published on the Internet; https://powo.science.kew.org/ Accessed: 3/28/2025.

Smith, Stephen. “Continuing impact of crab herbivory on Cape Cod salt marshes, a synopsis of vegetation-restoration techniques to reverse vegetation losses, and the future of these ecosystems in the face of climate change." Presentation at the Cape Cod Natural History Conference 2024.

Staudinger, M.D., A.V. Karmalkar, K. Terwilliger, K. Burgio, A. Lubeck, H. Higgins, T. Rice, T.L. Morelli, A. D'Amato. 2024. A regional synthesis of climate data to inform the 2025 State Wildlife Action Plans in the Northeast U.S. DOI Northeast Climate Adaptation Science Center Cooperator Report. 406 p. https://doi.org/10.21429/t352-9q86

Contact

| Date published: | April 15, 2025 |

|---|