- Scientific name: Coccyzus erythropthalmus

- Species of Greatest Conservation Need (MA State Wildlife Action Plan)

Description

Black-billed cuckoo (Coccyzus erythropthalmus)

The black-billed cuckoo is a neotropical migrant bird that is particularly elusive due to its skulking behavior, making it much more common to hear rather than see this bird. Males and females will sing a series of toot notes on the same pitch. This slender and long-tailed cuckoo is not sexually dimorphic. Adults can be distinguished from juveniles by their red orbital ring compared to the yellowish ring in young birds. The species can be distinguished from the similar yellow-billed cuckoo by both subtle plumage and vocalization characteristics. Cuckoos are well known to be voracious predators of caterpillars (especially pest species like tent caterpillars and spongy moth larvae), and they initiate nesting coinciding with caterpillar and cicada outbreaks.

Life cycle and behavior

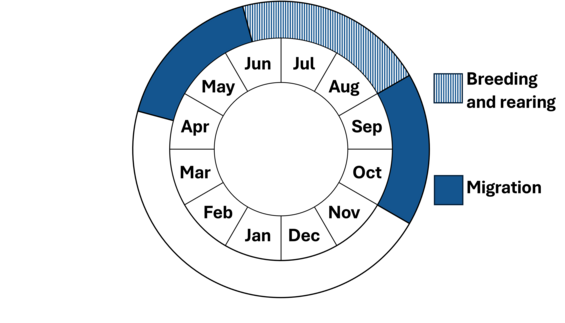

The black-billed cuckoo is a long-distance migrant songbird that spends the winter months in northwest South America, although very little is known about its precise winter areas and habitats. This species is one of the last of the migrant birds to return in the spring with peak arrivals in late May and early June. Nests are usually located in shrubs or small trees and often located along the forest edge or in shrubby areas. They are thought to be single brooded (although will renest after nest failure) with a typical clutch containing 2-3 eggs. Black-billed cuckoos have a very fast nesting cycle that includes an 11-day incubation and 7-day nestling period. Despite leaving the nest quickly, fledglings are initially restricted to jumping between branches as they do not gain flight ability until approximately three weeks after hatching. As with other life-cycle stages, little is known about the ecology of chicks once they gain flight proficiency. Fall migration starts in late August, peaks in September, but some individuals don’t appear to leave breeding areas until early October.

Figure 1. Phenology in Massachusetts. This is a simplification of the annual life cycle. Timing exhibited by individuals in a population varies, so adjacent life stages generally overlap each other at their starts and ends.

Population status

In Massachusetts, the black-billed cuckoo was at its peak abundance when farmland dominated the landscape and was thought to be particularly beneficial in orchards where they helped to control pest species. Their population declined as the majority of farmland habitat was either developed or regenerated to forest. Data from both the Breeding Bird Survey and the Massachusetts Breeding Bird Atlases indicate the decline of this species has continued over the last 45 years.

Distribution and abundance

Their breeding range includes eastern and central portions of the northern United States and southern Canada.

Habitat

Breeding habitat for the black-billed cuckoo includes areas of dense understory such as forest edges and thickets, often associated with wet areas (e.g., bogs, marshes, riparian areas). They are most common in brushy areas within deciduous or mixed forest types but are also documented nesting within coniferous forests. Although their nesting habitat is similar to that of the yellow-billed cuckoo, the black-billed cuckoo is found more frequently in areas with extensive woodlands.

Healthy habitats are vital for supporting native wildlife and plants. Explore habitats and learn about conservation and restoration in Massachusetts.

Black-billed cuckoo (Coccyzus erythropthalmus)

Threats

The primary threat to black-billed cuckoos in Massachusetts is loss and degradation of breeding habitat. Loss and fragmentation of young forest habitat is particularly acute in Massachusetts. Because of the species tendency to forage on caterpillars in orchards, they may be especially susceptible to pesticide contamination. Other threats include collisions with human-made structures and an increase in mortality associated with elevated numbers of mesopredators, including domestic cats.

An additional threat to the species is collisions with buildings and other structures, as approximately 1 billion birds in the United States are estimated to die annually from building collisions. A high percentage of these collisions occur during the migratory periods when birds fly long distances between their wintering and breeding grounds. Light pollution exacerbates this threat for nocturnal migrants as it can disrupt their navigational capabilities and lure them into urban areas, increasing the risk of collisions or exhaustion from circling lit structures or areas.

Predation by domestic cats has been identified as the largest source of mortality for wild birds in the United States with the number of estimated mortalities exceeding 2 billion annually. Cats are especially a threat to those species that nest on or near the ground.

Conservation

Habitat management is an important component to promote the conservation of this species in Massachusetts. Maintaining large forest blocks hosting a mosaic of forest types including young forest and shrubby habitat in which this species uses for nesting should benefit the cuckoo. Promote responsible pet ownership that supports wildlife and pet health by keeping cats indoors and encouraging others to follow guidelines found at fishwildlife.org.

Bird collision mortalities can be minimized by making glass more visible to birds. This includes using bird-safe glass in new construction and retrofitting existing glass (e.g., screens, window decals) to make it bird-friendly and reducing artificial lighting around buildings (e.g., Lights Out Programs, utilizing down shielding lights) that attract birds during their nocturnal migration.

References

Forbush, E. 1927. Birds of Massachusetts and Other New England States. Norwood Press. Norwood, MA.

Hughes, J. M. (2020). Black-billed Cuckoo (Coccyzus erythropthalmus), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (P. G. Rodewald, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.bkbcuc.01

Sauer, J.R., J.E. Hines, J.E. Fallon, K.L. Pardieck, D.J. Ziolkowski, Jr., and W.A. Link. 2022. The North American Breeding Bird Survey, Results and Analysis 1966 – 2022. Laurel, MD.

Veit, R., and W.R. Petersen. 1993. Birds of Massachusetts. Massachusetts Audubon Society, Lincoln, Massachusetts.

Walsh, J. and W.R. Petersen. 2013. Massachusetts Breeding Bird Atlas 2. Massachusetts Audubon Society and Scott & Nix, Inc.

Contact

| Date published: | April 28, 2025 |

|---|