- Scientific name: Piptochaetium avenaceum

- Species of Greatest Conservation Need (MA State Wildlife Action Plan)

Description

Flowering head

Black oatgrass, Piptochaetium avenaceum, is a loosely clumping perennial in the grass family (Poaceae). Black oatgrass grows 5-10 dm (50-100 cm or 20-40 in) tall. The leaf sheaths are glabrous (have no hairs), its membranous ligule is ovate and 2-3 mm (0.08-0.12 in) long, and the leaf blades are 20-30 cm (8.0-12.0 in) long and only 1-2 mm (0.04-0.08 in) wide, and usually involute (edges rolled inward). The flowering panicle is 10-20 cm (3.9-7.9 in) tall, open, and few-flowered. Each of the slender, divergent branches has only 1 or 2 spikelets.

Grass spikelets consist of specialized parts. To positively identify black oatgrass and other members of the grass family, a technical manual should be consulted. Species in this family have tiny, mostly wind-pollinated flowers. Two outer bracts on the outside of each spikelet are known as glumes. Between the glumes there are one or more florets. Each grass flower has a lemma and palea on either side of the stamens and pistil. Sometimes one or more parts will have an awn (a long, stiff, hairlike extension), or will be missing, or will be pubescent on the outside or along the veins. Measurements and characteristics of each are important in identifying grasses to species.

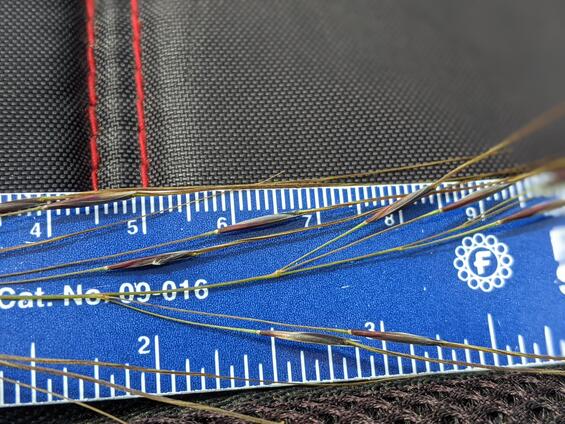

In black oatgrass, the branches of the inflorescence are in pairs. The membranous glumes are 9-13 mm (0.35-0.51 in) long and abruptly come to a point. Lemmas on the mature spikelet are dark brown, 7.5-11 mm (0.30-0.43 in) long and are villous in the bottom third, glabrous in the middle, and scabrous at the tip, with a persistent, scabrous awn that is 4.5-7 cm (1.8-2.8 in) long. Early in the summer, this awn is straight. Seeing many of these long awns together in several flowering heads is eye-catching and the easiest time to locate and identify the species. Later in the season, these awns begin bending sharply (geniculate) twice near the middle about 1 cm (0.39 in) apart and become spiraled at the base.

Mature seed

Habit of plants

Developing seed of black oatgrass close up.

Fruiting head of black oatgrass in mid-June.

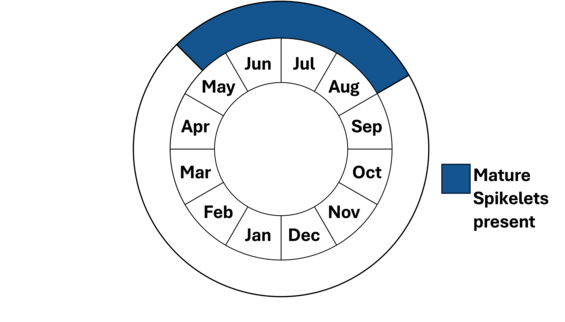

Life cycle and behavior

Black oatgrass is a perennial clumping grass species that is wind-pollinated. It is recognizable from mid-May into August. The lemma and palea fall with the seed, leaving the empty glumes on the plant. The long awn helps to distribute the seed, getting stuck in fur or feathers of passing animals. The awn is hydroscopic, sensitive to changes in air and environmental humidity, bending and spirally as the moisture levels change. If the seed lands pointing down, this bending action assists in establishing the seed’s contact with the soil, increasing the likelihood of germination.

Population status

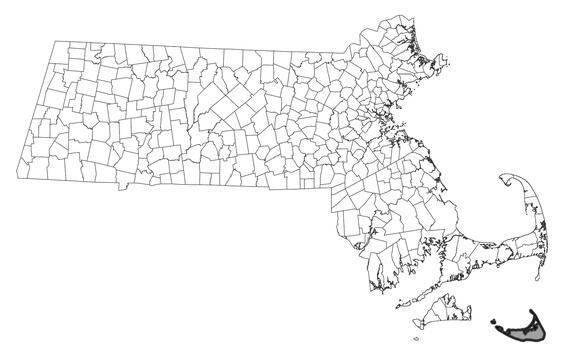

Black oatgrass has recently been listed as a species of greatest conservation need and is maintained on the plant watch list. There are only 2 occurrences in the state verified since 1999 found in Bristol and Nantucket Counties. There is 1 historical occurrence located in Barnstable County. iNaturalist contains 12 “research grade” observations from the past 5 years which have been found in Barnstable, Dukes, and Nantucket Counties (iNaturalist 2025). In addition, the Consortium of Northeastern Herbaria has 9 collections within the past 25 years from Barnstable, Bristol, Dukes, Franklin, and Nantucket Counties. It contains an additional 62 collections that were observed in Massachusetts prior to 1999 (CNH 2025).

Distribution and abundance

Black oatgrass is found over much of eastern North America. Its range extends from Ontario, south along the eastern seaboard to Florida and west to Texas and Michigan. There is a disjunct population(s) in Minnesota. It is of conservation concern in the northeastern portion of its range, including critically imperiled in Ohio and Pennsylvania, presumed extirpated in Ontario, imperiled in New York, Oklahoma, and West Virginia. In New England, it is not known in Maine or Vermont, critically imperiled in New Hampshire, and has not been given a rank in Connecticut, Massachusetts or Rhode Island (NatureServe 2025).

Distribution in Massachusetts. 1999-2024. Based on records in the Natural Heritage Database

Habitat

In Massachusetts, black oatgrass is known from sandy dry oak and pine woods or sandplain grasslands in the southeastern portion of the state.

Healthy habitats are vital for supporting native wildlife and plants. Explore habitats and learn about conservation and restoration in Massachusetts.

Many stems of flowering black oatgrass mixed with winged sumac, showing shiny appearance of long awns all together in grassy habitat in mid-June.

Threats

Black oatgrass is threatened by development, road maintenance, invasive plant species, and a lack of fire on the landscape.

Conservation

Survey and monitoring

Survey and monitoring are needed for this rare grass. Both the current and historic populations should be revisited, and information collected on the size of the population and any threats recorded and reported to MassWildlife Natural Heritage and Endangered Species Program. It is best surveyed during June and July when it has mature florets.

Management

The exact ecological needs of this species are not known. Known threats include invasive plant species, development and a lack of fire on the landscape. If possible, land protection should be included as part of the management for this species, particularly areas where prescribed fire could occur. All active management of rare plant populations (including invasive species removal) is subject to review under the Massachusetts Endangered Species Act and should be planned in close consultation with the MassWildlife’s Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program.

Research needs

As this plant is under-surveyed, more standard information is needed such as lists of associated species, comments on habitat quality and threats, and assessments of soil conditions and phenology. Research is needed to determine whether this plant can be grown in a nursery or garden setting for purposes of reintroductions. If habitat degradation accelerates losses of current populations, this strategy could prove useful to the long-term conservation of this species.

Acknowledgements

MassWildlife acknowledges the assistance of Matthew Charpentier who initiated the development of this fact sheet.

References

Fernald, M. L. 1950. Gray’s Manual of Botany, Eighth (Centennial) Edition—Illustrated. American Book Company, New York.

Gleason, Henry A., and Arthur Cronquist. Manual of Vascular Plants of Northeastern United States

and Adjacent Canada, Second Edition. Bronx, NY: The New York Botanical Garden, 1991.

Haines, A. 2011. Flora Novae Angliae – a Manual for the Identification of Native and Naturalized Higher Vascular Plants of New England. New England Wildflower Society, Yale Univ. Press, New Haven, CT.

Herbarium specimen data provided by: [Albion R. Hodgdon Herbarium (University of New Hampshire), Charles B. Graves Herbarium (Connecticut College), George Safford Torrey Herbarium (University of Connecticut), Herbarium of the Arnold Arboretum (Harvard University Herbaria), MBLWHOI Library Herbarium, New England Botanical Club (Harvard University Herbaria); The Gray Herbarium (Harvard University Herbaria), The Nantucket Maria Mitchell Association Herbarium, The Polly Hill Arboretum Herbarium; University of Massachusetts Amherst Herbarium, University of Vermont, Pringle Herbarium, New England vascular plants and Yale university Herbarium, Yale Peabody Museum] (Accessed through the Consortium of Northeastern Herbaria web site, www.neherbaria.org, accessed 4/11/2025).

iNaturalist 2025. Available from https://www.inaturalist.org. Accessed 4/11/2025

Magee, Dennis W. and Harry E. Ahles. Flora of the Northeast: a manual of the vascular flora of New England and adjacent New York. 1999. The University of Massachusetts Press, Amherst.

NatureServe. 2025. NatureServe Network Biodiversity Location Data accessed through NatureServe Explorer [web application]. NatureServe, Arlington, Virginia. Available https://explorer.natureserve.org/. Accessed: 4/11/2025.

POWO (2025). Plants of the World Online. Facilitated by the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Published on the Internet; https://powo.science.kew.org/ Accessed: 4/11/2025.

Seymour, Frank C. 1969. The Flora of New England, First edition. Charles E. Tuttle Company, Inc. Tokyo, Japan.

Contact

| Date published: | May 5, 2025 |

|---|