- Scientific name: Alosa aestivalis

- Species of Greatest Conservation Need (MA State Wildlife Action Plan)

Description

Blueback herring (Alosa aestivalis)

The blueback herring is a member of the herring family, similar in appearance to the alewife, but the diameter of the blueback's eye is less than or equal to the length of the snout, and the peritoneal lining of the body cavity is pigmented sooty-black. The blueback herring's back and upper sides tend to be a bluish color. Adults are usually 25-30 cm (10-12 in) total length in length. Young-of-the-year are generally less than 8 cm (3 in) long while in freshwater. Blueback are described as fluvial specialists because no landlocked populations exist in Massachusetts, although landlocked populations do appear elsewhere. They are tolerant of warm waters as adults can remain in freshwater habitat until July and juveniles spend one to several months in freshwater before emigrating to the sea in summer or fall depending on water temperature, water quality and food supply.

Life cycle and behavior

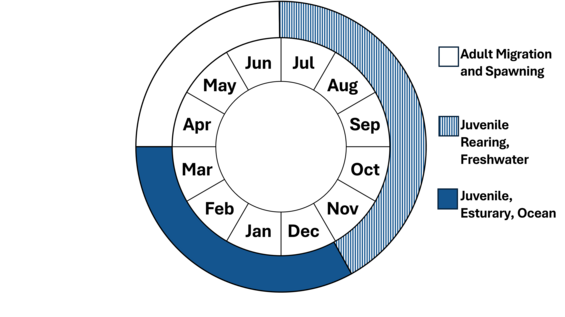

Blueback herring are anadromous but can establish landlocked populations. Anadromous populations spend most of their adult life in coastal marine waters and return to freshwaters to spawn in the spring. Spawning occurs in swift-flowing sections of rivers and streams with gravel or rocky bottoms as well as coves and backwaters of large rivers. They may also spawn in lakes and ponds with access to the sea. Although the annual spawning migrations are physiologically stressful, most adults survive, return to the sea and can repeat the process in subsequent years. The young form large schools and slowly work their way downstream. They all enter saltwater before their first winter. In freshwater, young bluebacks eat copepods and some cladocerans. In marine waters, adults feed on a variety of marine invertebrates, including ctenophores, calanoid copepods, amphipods, mysids, other pelagic shrimps, and small fish. Their first spawning migration occurs at two to four years of age. They can live to eight years.

Population status

Alewife (top) and blueback herring (bottom)

The 2024 River Herring Benchmark Stock Assessment (ASMFC 2024) found the coastwide populations of both alewife and blueback herring were depleted relative to historic levels. The “depleted” determination was used instead of “overfished” to indicate factors besides fishing have contributed to the decline, including habitat loss, predation, and climate change.

U.S. National Marine Fisheries Service lists blueback herring as Species of Concern, meaning that it has some concerns regarding status and threats, but for which insufficient information is available to list the species under the U.S. Endangered Species Act.

Distribution and abundance

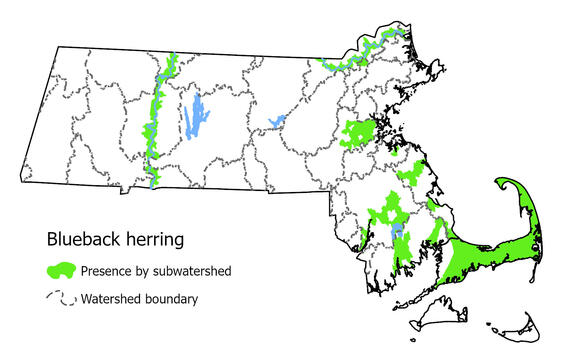

Native to the Atlantic coast of North America from maritime Canada to Florida. Blueback herring were once highly abundant in Massachusetts and entered numerous coastal streams and the

Connecticut and Merrimack rivers. Since they were often confused with alewives, little specific information is available regarding their historical commercial harvest, recreational harvest and metrics of population abundance. Blueback runs are less common than alewife runs in Massachusetts. Of the 170 river herring runs listed in the Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries’ (DMF) coast-wide survey of anadromous fish runs (Reback et al. 2004 and 2005), 86 are listed as having alewife, 40 are listed as having blueback herring, and 44 are listed as river herring (species unknown).

Habitat

Blueback herring are found in shallow marine waters (<100 m; 328 ft) along the continental shelf where they co-occur with alewife, American shad, Atlantic herring, and Atlantic mackerel. Blueback herring spawn in a wide range of lotic environments connected to the ocean.

Healthy habitats are vital for supporting native wildlife and plants. Explore habitats and learn about conservation and restoration in Massachusetts.

Threats

Like other river herrings, blueback herring populations have been reduced or eliminated in some areas by damming and pollution. Other factors that have caused the decline in this species are alteration of freshwater habitats, declines in water quality and quantity, historic over-fishing and current bycatch in other regulated fisheries.

Climate change may be a problem going forward as diadromous fish are among the functional groups with the highest overall vulnerability to climate change based on a recent marine and migratory fish vulnerability assessment (Hare et al. 2016). Marine habitats are affected as ocean temperature over the last decade in the U.S. Northeast Shelf and surrounding Northwest Atlantic waters have warmed faster than the global average (Pershing et al. 2015). New projections also suggest that this region will warm two to three times faster than the global average from a predicted northward shift in the Gulf Stream (Saba et al. 2016). Freshwater habitats will be affected by a high rate of sea-level rise, increases in the magnitude of extreme precipitation events, and increases in the magnitude and frequency of floods (Hare et al. 2016).

Further research and monitoring are required.

Conservation

Recreational and commercial harvest of river herring was prohibited in Massachusetts in 2006 out of concern over their status. As of January 2012, all directed harvest of river herring in all Atlantic Coast state waters is prohibited unless states have approved sustainable fisheries management plans (SFMP). To date, two SFMP for river herring spawning run harvests have been approved.

Large cooperative aquatic restoration projects have increased in recent decades in Massachusetts. Dam removals, fishway construction and channel improvements have increased, with some documentation of spawning run abundance improvements, since the harvest ban in 2006. DMF provides technical assistance to counting efforts on river herring spawning runs in Massachusetts (Nelson 2006) and annually samples biological data on spawning adults at eight of the counting stations (Sheppard and Chase 2024). Twenty-nine of the counting stations were reviewed in the recent river herring stock assessment with 11 accepted as indices of abundance (ASMFC 2024). DMF also conducts river herring spawning and nursery habitat assessments to confirm habitat suitability for river herring early life history, and document impairments and restoration potential (Chase et al. 2020). Habitat assessment reports are published in the DMF Technical Report series.

References

Chase, B.C., J.J. Sheppard, B.I. Gahagan, and S.M. Turner. 2020. Quality Assurance Program Plan (QAPP) for Water Quality Measurements Conducted for Diadromous Fish Habitat Monitoring. Version 2.0. Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries Technical Report TR-73.

This species description was adapted, with permission, from:

Hartel, Karsten E., David B. Halliwell, and Alan E. Launer. Inland Fishes of Massachusetts. Lincoln: Massachusetts Audubon Society, 2002.

National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS). Status Review Report: Alewife (Alosa pseudoharengus) and Blueback Herring (Alosa aestivalis). Silver Spring, MD: U.S. Department of Commerce, 2019.

Hare, J. A., W. E. Morrison, M. W. Nelson, M. M. Stachura, E. J. Teeters, R. B. Griffis, M. A. Alexander, and A. S. Chute. "A Vulnerability Assessment of Fish and Invertebrates to Climate Change on the Northeast US Continental Shelf." PloS One 11, no. 2 (2016): e0146756.

Pershing, A. J., M. A. Alexander, C. M. Hernandez, L. A. Kerr, A. Le Bris, K. E. Mills, and G. D. Sherwood. "Slow Adaptation in the Face of Rapid Warming Leads to Collapse of the Gulf of Maine Cod Fishery." Science 350, no. 6262 (2015): 809-812.

Reback, K.E., P.D. Brady, K.D. McLauglin, and C.G. Milliken. 2004a. A survey of anadromous fish passage in coastal Massachusetts: Part 1. Southeastern Massachusetts: Part 1. Mass. Div. Mar. Fish. Tech. Report No. 16.

Reback, K.E., P.D. Brady, K.D. McLauglin, and C.G. Milliken. 2004b. A survey of anadromous fish passage in coastal Massachusetts: Part 2. Cape Cod and the Islands. Mass. Div. Mar. Fish. Tech. Report No. 16.

Reback, K.E., P.D. Brady, K.D. McLauglin, and C.G. Milliken. 2005a. A survey of anadromous fish passage in coastal Massachusetts: Part 3. South Coastal. Mass. Div. Mar. Fish. Tech. Report No. 17.

Reback, K.E., P.D. Brady, K.D. McLauglin, and C.G. Milliken. 2005b. A survey of anadromous fish passage in coastal Massachusetts: Part 4. Boston and North Coastal. Mass. Div. Mar. Fish. Tech. Report No. 18.

Saba, V. S., S. M. Griffies, W. G. Anderson, M. Winton, M. A. Alexander, T. L. Delworth, and R. Zhang. "Enhanced Warming of the Northwest Atlantic Ocean Under Climate Change." Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans 121, no. 1 (2016): 118-132.

Sheppard, J.J., and B.C. Chase. 2024. Massachusetts American Shad and River Herring Monitoring Report: 2019. Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries Technical Report TR-82.

Contact

| Date published: | April 7, 2025 |

|---|