- Scientific name: Salix pedicellaris Pursh

Species of Greatest Conservation Need (MA State Wildlife Action Plan)

Description

Salix pedicellaris (bog willow) is a clonal shrub in the Salicaceae. Although identification of willows is often difficult, bog willow is one of the more distinct species (Argus 2006). The shrubs are relatively short in stature, typically about meter (3.2 ft) but can be as tall as 1.5 m (5 ft). Twigs of bog willow are smooth and lack stipules. The alternate, smooth-margined leaves are oblong, widest in the middle and more narrow toward both ends and range from 19-53 mm (0.75-2.1 in) in length and 5-20 mm (0.2-0.8 in) across. The leaves are usually bright green above and paler below, becoming leathery as they age. A whitish, waxy coating may be present on one or both leaf surfaces but it is most often on the underside. Staminate and pistillate flowers are borne on separate plants. Both male and female Salix flowers are produced in cylindrical clusters known as catkins, and those of Bog Willow are somewhat loosely flowered. (Fernald 1950, Gleason and Cronquist 1991, Argus 2020, Dodds 2022).

Life cycle and behavior

Bog willow is a shrub and generally flowers every year. Male and female flowers are on separate plants. It is likely both wind and insect pollinated. Seed dispersal is by wind and water.

Population status

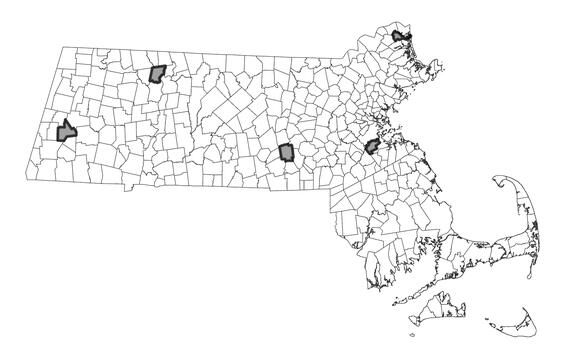

Bog willow has been tracked by MassWildlife’s Natural Heritage Endangered Species Program (NHESP) as a watch list species since 1988 and has 9 records since that time. In a 3000-hour fieldwork survey of all 26 towns in Franklin County over the prior decade, the species was found in only one town (Bertin et al 2020). The only other counties with records are Berkshire, Essex and Norfolk (Cullina et al. 2011). As of 10 April 2025, iNaturalist has only 1 research grade observations for this species in Massachusetts. Historically, there are 138 specimen records including Middlesex, Norfolk, Suffolk, and Worcester Counties but only 30 collected in the past 90 years, indicating a decline (CNH 2025, Cullina et al. 2011).

Distribution in Massachusetts

1999-2024

Based on records in the Natural Heritage Database

Distribution and abundance

Bog willow is a widespread species across northern latitudes in North America, however in the 9 northeastern most states in the U.S. it is quite rare. There are only 30 research grade observations on iNaturalist, despite this being a relatively easy willow to identify. It is more common in northern Michigan, Wisconsin, Minnesota, and Ontario. The range extends from there westward to Alberta and British Columbia with 610 research grade observations on iNaturalist for the entire range. In New England, it is ranked Ss (imperiled) in Vermont and New Hampshire, possibly extirpated in Rhode Island, S1 in Connecticut (critically imperiled), and apparently secure (S4) in Maine (NatureServe 2025).

Habitat

Bog willow is an obligate wetland species that occurs typically in sun or partial shade in swamps, bogs, fens, marshes, pond shores and wet meadows. In Massachusetts, it appears to vary in its substrate and water pH preferences from slightly acidic to calcium rich and from fertile soils to sandy, nutrient poor soils. Where it is found, other rare wetland habitat specialist plant species are also present. On at least two sites, it appears along with a wetland species that is a known pyrophyte (i.e. a plant that thrives with fire). On one site it has been found in association with the following species (a partial list) Acer rubrum (red maple), Alnus incana (speckled alder), Betula alleghaniensis (yellow birch), Bromus ciliatus (fringed brome), Calamagrostis canadensis (bluejoint grass), Carex comosa (bristly sedge), Carex hystericina (porcupine-sedge), Carex lacustris (lakeside sedge), Carex lasiocarpa (woolly-fruited sedge), Carex prairea (prairie-sedge), Carex stricta (tussock-sedge), Chamaedaphne calyculata (leatherleaf), Equisetum fluviatile (river-horsetail), and Fraxinus nigra (black ash).

Healthy habitats are vital for supporting native wildlife and plants. Explore habitats and learn about conservation and restoration in Massachusetts.

Threats

Bog willow is threatened by succession when open wetlands becoming overgrown with shrubs and trees, and by problematic invasive species such as glossy buckthorn (Frangulaalnus), purple loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria), reed canary grass (Phalaris arundinacea) and giant reed grass (Phragmites australis) which can all grow quickly and thickly, shading and crowding out lower stature plants such as bog willow. Fire suppression may be a threat. Disruption of the natural hydrologic regime is also a threat. Beaver dams causing significant water level increases in wetland basins can also create unfavorable conditions for this species. This being a species of more northerly distribution, climate warming is a potential threat. The past 130 years have seen a warming of 1.4 ⁰C, (2.5 ⁰F) in the Northeast United States (Staudinger et al. 2024). Northern species can be expected to move much further north in an attempt to occupy a habitat within their evolved climate envelope.

Conservation

Survey and monitoring

Much more survey work is needed for new populations. Given these are woody shrub species, monitoring could be done on a five-year cycle in the growing season with estimates of plant vigor and seed production and including a threat assessment. Special emphasis should be made to target known sites that are 20 or more years overdue for survey and monitoring.

Management

An important aspect to management of wetlands is to remove and reduce populations of all invasive species, especially those mentioned in the threat section. In some areas brush and shrub removal may be needed. This is typically done in winter on frozen ground. Another aspect for this species will be to watch for altered water levels from beaver activity, development, ditches, or road building. As stated above, there is some indication that if these open wetlands are managed with prescribed fire with a fire return interval of 10 years, this species may be favored.

Research needs

As this plant is under-surveyed, a serious effort should be made to conduct de novo surveys in areas where this is likely to occur or where records are over 100 years old. Additionally, standard information is needed such as lists of associated species, comments on habitat quality and threats, assessments of water levels and chemistry, phenology, sensitivity to deer browse, and response to prescribed fire. Research is needed to determine whether this plant can be grown in a nursery or garden setting for purposes of reintroductions. If habitat degradation accelerates losses of current populations, this strategy could prove useful to long-term conservation of this species.

References

Argus, George W. Page updated November 5, 2020. Salix pedicellaris Pursh. In: Flora of North America Editorial Committee, eds. 1993+. Flora of North America North of Mexico [Online]. 22+ vols. New York and Oxford. Accessed 10 April 2025 at http://floranorthamerica.org/Salix_pedicellaris

Bertin, R. I., M. G. Hickler, K. B. Searcy, G. Motzkin, and P. P. Grima. 2020. Vascular Flora of Franklin County, Massachusetts. New England Botanical Club.

CNH 2025 Consortium of Northeastern Herbaria web site, www.neherbaria.org, accessed 25 Feb 2025.

Cullina, M., B. Connolly, B. Sorrie, and P. Somers. 2011. The vascular plants of Massachusetts: a county checklist, 1st revision. Massachusetts Natural Heritage & Endangered Species. Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife, Westborough, MA.

Dodds, Jill S. 2022. Salix pedicellaris Rare Plant Profile. New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection, State Parks, Forests & Historic Sites, State Forest Fire Service & Forestry, Office of Natural Lands Management, New Jersey Natural Heritage Program, Trenton, NJ. 17 pp. https://www.nj.gov/dep/parksandforests/natural/heritage/docs/salix-pedicellaris-bog-willow.pdf

Fernald, M. L. 1909. Salix pedicellaris and its variations. Rhodora 11(128): 157–162.

Fernald, M. L. 1950. Gray’s Manual of Botany, Eighth (Centennial) Edition—Illustrated. American Book Company, New York.

Gleason, Henry A., and Arthur Cronquist. Manual of Vascular Plants of Northeastern United States and Adjacent Canada, Second Edition. Bronx, NY: The New York Botanical Garden, 1991.

Haines, Arthur. Flora Novae Angliae. New England Wild Flower Society, Yale University Press, New Haven, CT. 2011.

iNaturalist. Available from https://www.inaturalist.org. Accessed 10 April 2025

Native Plant Trust. 2025. Go Botany website. https://gobotany.nativeplanttrust.org/ Accessed 10 April 2025

NatureServe. 2025. NatureServe Network Biodiversity Location Data accessed through NatureServe Explorer [web application]. NatureServe, Arlington, Virginia. Available https://explorer.natureserve.org/. Accessed: 10 April 2025

Staudinger, M.D., A.V. Karmalkar, K. Terwilliger, K. Burgio, A. Lubeck, H. Higgins, T. Rice, T.L. Morelli, A. D'Amato. 2024. A regional synthesis of climate data to inform the 2025 State Wildlife Action Plans in the Northeast U.S. DOI Northeast Climate Adaptation Science Center Cooperator Report. 406 p. https://doi.org/10.21429/t352-9q86

Contact

| Date published: | May 12, 2025 |

|---|