- Scientific name: Sternotherus odoratus

Species of Greatest Conservation Need (MA State Wildlife Action Plan)

Description

Eastern musk turtle, showing the two stripes on its head, a common physical characteristic seen on this species.

The eastern musk turtle is placed within the turtle family Kinosternidae (mud and musk turtles). It is a small freshwater turtle species, averaging 5-12 cm (2-5 in) in carapace (upper shell) length. This species has a smooth, domed, tan, dark brown, or gray carapace that often has an irregular pattern of yellow/brown flecks or streaks on each scute (keratinous plates that form the shell), commonly covered by algae. Their plastron (underside of the shell) is small and cross-shaped with a movable plastron. The plastron is pale pink to brown in color, and the surrounding exposed underbelly skin between the scutes is white to yellowish, or pinkish in some individuals. The eastern musk turtle has gray-to-blackish colored skin, and their face and neck are tan to black, with stripes of white or yellow along with occasional spots on their lower neck and legs and heavily webbed feet. Two distinct yellow-to-white stripes are on each side of their head, one running above the eye and one below, both meeting at their pointed, triangular-shaped snout. They also sport a stripe on each side of their lower jaw and have a pair of barbels on their chin and tubercles on their throat when fully outstretched. In older individuals, these markings can be faint or obscured.

An old male eastern musk turtle with indistinct head markings, lacking the two characteristic head stripes commonly seen in this species.

Eastern musk turtles are sexually dimorphic. Males have a larger carapace than females and possess a thicker tail extending beyond the carapace's posterior edge. Males additionally have two small pads of raised scales on the interior of their hind legs, used to provide additional grip during mating. Both sexes possess musk glands at the margins of their plastron that emit a malodorous secretion when disturbed, giving them the local nickname “stinkpot.”

Eastern musk turtle hatchlings emerge from their eggs around 18 mm (0.7 in) in carapace length and appear very similar to adults outside of a few key characteristics. They have multiple keels or ridges that run along the midline of their carapace, and their vertebral (spine) scutes do not overlap like roofing slates. Hatchlings also feature yellow or white spots on the posterior half of each marginal scute, along with more distinct head markings than adults.

Similar Species: Eastern musk turtles may be mistaken for young painted turtles (Chrysemys picta) due to their similar dark carapaces and white-to-yellow striped markings on their forearms and skin. However, unlike eastern musk turtles, painted turtles have a yellow-to-orange plastron and their carapace scutes are darker black or brown, outlined in olive-green on the vertebral and costal scutes, and red on the marginal scutes. Painted turtles also have a distinctive, yellow stripe behind the eye and along their tympanum (ear), a rounded beak, and are on average, much larger than the eastern musk turtle, averaging 12-18 cm (4.5-7 in) in carapace length.

Life cycle and behavior

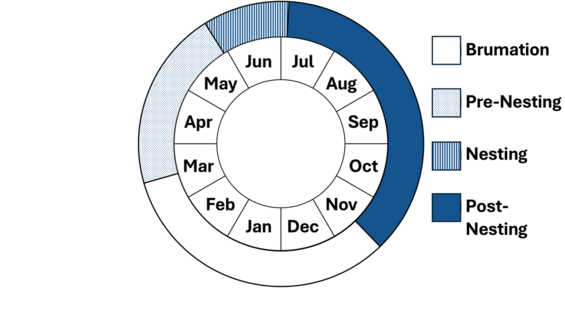

The eastern musk turtle is a highly aquatic species. In southern populations, such as those in Florida and south-central Texas, musk turtles can remain active all year-round, while northern populations are generally active from only April to October (with a longer activity season in warm years). In northern regions like Massachusetts, temperature cycles may influence their day-to-day activity, making them more crepuscular— active at dawn and dusk. During midday, they are typically inactive, aestivating or resting in the mud or detritus at the bottom of a body of freshwater. Eastern musk turtles, on average, reach sexual maturity between 4-11 years of age, with southern populations maturing faster than those in the north, and can live more than 27 years in the wild. Courtship and mating occur mainly in April and May but can occur sporadically throughout the year, with peaks in the spring and fall. Mating occurs in the water.

A male (turtle on top) and female (turtle on bottom) Eastern musk turtle courting underwater.

In Massachusetts, female eastern musk turtles nest from late May to early July, preferring to nest on an open, south-facing, steep slope close to their inhabited waterbody. Females will nest during dawn or dusk and deposit 1-8 eggs per clutch. In Massachusetts, a single female will lay 1-3 clutches a year to compensate for low recruitment levels. The average number of eggs per clutch for eastern musk turtles varies by geographic region. Many nests of eastern musk turtles are shallow, formed by scraping away debris and excavating the dirt with their hind feet. Females have also been observed laying nests under fallen logs, stumps, and even within the walls of muskrat lodges. Occasionally, female eastern musk turtles will nest communally, piling their eggs together in a single nest, though this behavior is relatively uncommon.

It takes 80-113 days before hatchlings emerge from the nest. Eastern musk turtle eggs have temperature-dependent sex-determination (TSD), with incubation temperature determining the sex of the hatchlings: higher temperatures of 28˚C (82˚F) and above produce mostly females, while an incubation temperature of 25˚C (77˚F) results primarily in males. Nest predation rate is a concern for hatchling survival. Mesopredators such as raccoons (Procyon lotor), skunks (Mephitis mephitis), and coyotes (Canis latrans) target and prey on their nests, resulting in low nest success, with mortality rates as high as 96%. If hatchlings survive, they typically head for the nearest water body, attracted to the humidity and illumination, where they hide and forage on carrion, algae, and small aquatic macroinvertebrates. By the time they mature, eastern musk turtles remain omnivorous, feeding on seeds, mollusks, carrion, and vegetation, but their diet is also adaptive to their environment. For instance, river-dwelling eastern musk turtles tend to be more carnivorous and feed mainly on carrion and aquatic macroinvertebrates, whereas lake-dwelling turtles have a preferred diet of aquatic macrophytes.

Post-nesting season, eastern musk turtles will move to areas with cooler water to avoid desiccation, for the shallow areas they occupy in the spring (coves and backwaters) tend to dry up from the late summer heat. Once the summer transitions into fall, they prepare to overwinter or brumate by feeding and rehydrating one last time. They then burrow in soft organic substrate or debris underwater or in muskrat burrows, occasionally emerging for mild weather and conserving their energy until spring.

Population status

The eastern musk turtle’s conservation status is considered secure or apparently secure in most of the regions it inhabits in North America. However, this species is designated as vulnerable, imperiled, or critically imperiled in certain states and provinces, such as the states of Iowa and Maine and the provinces of Ontario and Québec. In Massachusetts, the eastern musk turtle is listed as apparently secure, because it occurs at high densities within specific regions of the state. However, its status is unknown, and there is no formal monitoring program in place, and it is considered a data-deficient species of greatest conservation need.

Distribution and abundance

The eastern musk turtle is native to the eastern region of North America, ranging from the Canadian provinces of Ontario and Québec, south to central Texas, northward to the Great Lakes Basin, and eastward along the eastern seaboard from Florida up to Maine. The species formerly occurred in Mexico but is believed to be extirpated there. In Massachusetts, they found throughout low-elevation portions of the mainland. They are not known from any island in Massachusetts.

Habitat

Eastern musk turtles are a highly aquatic species that seldom travels on land. They inhabit a variety of permanent freshwater systems with slow currents and soft bottoms such as: lakes, ponds, swamps, canals, sloughs, streams, rivers, and even ditches. They often spend time in the littoral zones of these water bodies (near the shore) that host aquatic vegetation for foraging and deeper areas for brumation (overwintering).

Healthy habitats are vital for supporting native wildlife and plants. Explore habitats and learn about conservation and restoration in Massachusetts.

Riverine habitat (top left) and coastal plain pond (top right) habitat commonly inhabited by Eastern musk turtles.

Threats

Though locally common in some rivers and ponds of eastern Massachusetts, eastern musk turtles face numerous threats, like many other freshwater turtle species, that are impacting their population stability.

- Mesopredators: Subsidized depredation from mesopredators (e.g., raccoons, skunks, opossums), cause high annual adult and nest mortality.

- Human Recreation: Human activities including land development and road construction fragment and destroy critical habitats for the eastern musk turtle, limiting their access to vital resources and increasing isolation between populations. Musk turtles can be killed or drowned by hooked fishing lines.

- Road Mortality: In certain populations, automobiles can significantly threaten eastern musk turtles. Roads and other impervious surfaces fragment their habitats and act as barriers, forcing them to cross these surfaces to travel towards nesting or foraging sites, placing them at high risk of automobile strikes.

- Climate Change: Increased global average temperatures may affect the availability of suitable overwintering sites, as this species is intolerant of anoxic aquatic conditions. Climate change can also affect nesting phenology. But overall, because this is a southern species with a wide range of suitable, permanent aquatic habitats, it is thought to be less vulnerable to climate change than more specialized turtle species.

A comprehensive approach involving habitat protection, road mitigation, and public education is essential for addressing these challenges.

Research Needs

There is only one comprehensive graduate thesis addressing eastern musk turtle ecology and demography in Massachusetts completed by Lori Johnson at Antioch University New England, and there remains a general lack of research and knowledge on this species within the state and across New England, compared to other regions. Consequently, potential threats and vulnerabilities to their populations are poorly understood. It is important to address these knowledge gaps about eastern musk turtle ecology in Massachusetts. These efforts include establishing a more robust population inventory within Massachusetts, creating a standardized protocol for sampling and trapping assessments, and conducting detailed research on this species’ movements and habitat selection.

Management Needs

Although no current research indicates that eastern musk turtle populations are declining in Massachusetts, factors such as road mortality, predation, human recreation, and climate change pose a threat. MassWildlife maintains a strong, ongoing relationship with the Massachusetts Department of Transportation (MassDOT), where the combined goal is to oversee and manage roadways to prevent turtle mortalities. Partnering with agencies such as the Department of Conservation and Recreation (DCR) is integral in managing land use, enhancing habitat quality, and incorporating plans around navigating the impacts of climate change. The following activities are warranted:

- Spatial monitoring of eastern musk turtles to understand the potential effects of dam removals and urbanization

- Public education and outreach to promote sustainable land practices and reduce fragmentation and habitat loss

- Increased efforts to protect, and promote connectivity between, large and resilient protections

Ultimately, increased effort in monitoring and management strategies that maintain functional, connected ecosystems will not only protect the eastern musk turtle from immediate threats but also bolster population health and resilience in the face of environmental and anthropogenic challenges.

References

Ernst, C.H. and J.E. Lovich. 2009. Turtles of the United States and Canada: Second Edition. John Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, MD, USA.

Goessling, J.M., C. Ward, and M.T. Mendonça. 2019. Rapid thermal immune acclimation in common musk turtles (Sternotherus odoratus). Journal of Experimental Zoology Part A: Ecological and Integrative Physiology 331, 3:185-191.

Johnson, L.M. 2009. “Reproductive ecology, demography, and causes in mortality in a population of Eastern Musk Turtle, Sternotherus odoratus (Latreille), in Central Massachusetts. Antioch University New England.

Roberts, H.P., L.L. Willey, M.T. Jones, D.I. King, T.S. Akre, J. Kleopfer, D.J. Brown, S.W. Buchanan, H.C. Chandler, P. deMaynadier, and M. and Winters. 2023. Effects of landscape structure and land use on turtle communities across the eastern United States. Biological Conservation, 283:110088.

Contact

| Date published: | April 17, 2025 |

|---|