- Scientific name: Nannothemis bella

Species of Greatest Conservation Need (MA State Wildlife Action Plan)

Description

Male elfin skimmer

The elfin skimmer is a small, slender insect belonging to the order Odonata, suborder Anisoptera (the dragonflies), and family Libellulidae (the skimmers), the largest dragonfly family in North America. The elfin skimmer is the only member of its genus Nannothemis. The species is a miniscule dragonfly with a white face, blue-gray eyes with a vertical brown stripe. Male thorax and abdomen start as grayish-black and when mature are pruinose blueish-white. Females are striped with yellow and black markings on thorax and abdomen giving an appearance of a bee.

Adult elfin skimmers range from 18-20 mm (0.7-0.8 in) in length. Fully developed nymphs and exuviae may range from 7-9 mm (~0.3 in). This is the smallest dragonfly in North America.

In Massachusetts, the species is most similar in appearance to whitefaces (Leucorrhinia) and eastern amberwing (Perithemis tenera). Elfin skimmer is smaller than these species, and does not have wing color patches, among other features. See keys in Tennessen (2019) for identification of nymphs and exuviae.

Life cycle and behavior

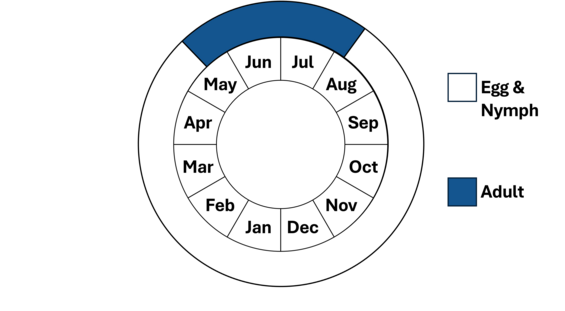

Note, nymphs are present year-round.

The egg and nymph life stages of the elfin skimmer are fully aquatic. The cryptic nymphs are predators likely feeding on smaller invertebrates. Nymphs undergo several molts (instars) for at least 2 years until they are ready to emerge as winged adults. Nymphs emerge up onto emergent vegetation primarily in late May. When the nymph reaches a secure substrate, the adult begins to push itself out of the exoskeleton. As soon as the abdomen and wings are fully expanded, the adult takes its first flight. This maiden flight usually carries the individuals up into surrounding forest or other areas away from wetlands, where they spend several days maturing and feeding and are somewhat protected from predation and inclement weather. Adult male elfin skimmers spend most of their time over breeding wetlands defending small territories from other males. Females occupy mostly wetland edges in riparian areas. Adults perch on shrubs and emergent vegetation often with their wings pushed forward. Like all dragonflies, elfin skimmers are predators feeding on small insects.

Breeding in Massachusetts probably occurs in June and July and has been rarely observed. Following mating, the female oviposits eggs in small open pools within sphagnum-dominated wetlands intermittently tapping the surface of water, while the male is guarding nearby.

Elfin skimmers emerge in late May and are on the wing until early August. Height of adult activity is likely in June.

Distribution and abundance

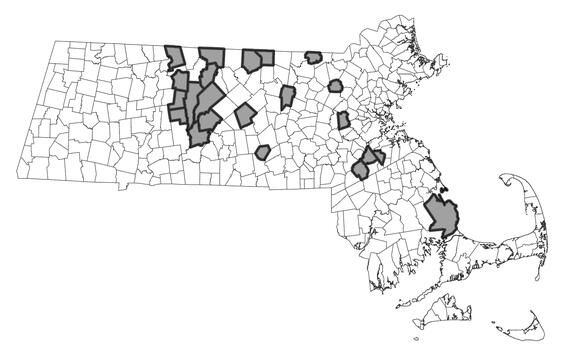

The elfin skimmer range extends from Florida and Alabama, north to Great Lakes region, and east into New England, New Brunswick and Nova Scotia. The species occurs in all New England states and supports some of the most suitable habitat in its range (Chandler et al. 2024). In Massachusetts, the species occurs in the Middle Connecticut, Millers, Chicopee, Nashua, Blackstone, Concord, Charles, Neponset, Taunton, and Cape Cod watersheds. Species occurrences are scattered across central and eastern MA watersheds often at watershed boundaries where bogs and fens may form or along the edges of pond and streams. The species have been found in low and high abundances. The species status remains uncertain in Massachusetts.

Distribution in Massachusetts.

1999-2024

Based on records in iNaturalist, Odonata Central, and Natural Heritage databases.

Habitat

Elfin skimmer inhabits sphagnum-rich wetlands including bogs, fens, and lakes and ponds and streams with boggy edges. Wetlands can have thick or floating spaghum mats, abundant silt, abundant graminoid vegetation, and minimal open water (Brown 2020). The adults also inhabit fringes of surrounding forests but are mostly observed over wetlands.

Healthy habitats are vital for supporting native wildlife and plants. Explore habitats and learn about conservation and restoration in Massachusetts.

Bog habitat suitable for elfin skimmer.

Threats

The primary threat to elfin skimmer is wetland, riparian, and upland habitat destruction through physical alteration or pollution. In some portions of its range, the elfin skimmer habitat is under pressure from development, logging, peat mining, and resulting sedimentation. Permanent changes in water level from anthropogenic or beaver sources, invasive aquatic plant species, and various forms of pollution, such as road and agricultural runoff, septic system failure, and insecticides, are also potential threats. Climate change is likely major threat to this species. Models project a severe loss of high-quality suitable habitat and its distribution over the next 30-50 years (Chandler et al. 2024).

Conservation

Survey and monitoring

Standardized and targeted surveys for elfin skimmer are needed to determine its status in Massachusetts. Surveys should target historical and new wetland sites to determine species occupancy and population status. Surveys for adults are likely to be more effective for detection compared to nymph or exuviae surveys because of their small size and difficult to sample habitat. Adult surveys should target bog and fen habitats during their flight period at standardized weather and time windows to maximize species detection. Multiple site visits (e.g., ≥3) may be required to detect this species. Routine monitoring of prioritized sites is needed estimate occupancy trends overtime.

Management

Protection and restoration of wetlands and its surrounding upland habitat is crucial for elfin skimmer persistence in Massachusetts. Upland habitats adjoining the breeding sites should be maintained for roosting, hunting, and for newly emerged adults that are more susceptible to mortality from predation and inclement weather. Development of these areas should be discouraged, and the preservation of remaining undeveloped uplands should be a priority. Alternatives to commonly applied road salts should be tested to minimize freshwater salinization. Other actions to improve or prevent habitat degradation include reduction of nutrient, agricultural and road runoff; minimization of water level alteration and groundwater withdrawals; prevention and management of nonnative aquatic vegetation species; limitation and enforcement of off-road vehicles in wetland habitat; and connection between wetlands.

Research needs

Through standardized surveys, effort is needed to define habitat requirements, distribution, relative abundance, and potential breeding sites in Massachusetts. Research effort is needed to estimate detection and occupancy rates and how other environmental variables (e.g., sample timing, weather) affect these rates. Other research efforts include projections of species distribution under climate change scenarios and climate vulnerability analysis in Massachusetts, since this species occupies bog habitats.

References

Brown, V.A. 2020. Dragonflies and Damselflies of Rhode Island. Rhode Island Division of Fish and Wildlife, Department of Environmental Management, West Kingston RI.

Chandler M., D. Davis, L. Newton, A. Goodman, J. Ware. 2024. Looking out for the little guy: species distribution modeling and conservation implications of the elfin skimmer Nannothemis bella (Odonata: Libellulidae). International Journal of Odonatology 27:232-241.

Lam, E. Dragonflies of North America. Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press, 2024.

Nikula, B., J.L. Ryan, and M.R. Burne. A Field Guide to the Dragonflies and Damselflies of Massachusetts. 2nd ed. Massachusetts Natural Heritage and Endangered Species Program, 2007.

Paulson, D. Dragonflies and Damselflies of the East. Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press, 2011.

Tennessen, K. Dragonfly Nymphs of North America: An identification guide. Springer, 2019.

Contact

| Date published: | April 8, 2025 |

|---|