The development process

Residential development—especially multifamily residential development—is a complicated endeavor that involves numerous regulatory processes and players that vary with the size, type, location, and financing of the project. The diagram below provides a simplified overview of the steps involved in developing housing.

Site Control

To build housing, developers must begin with a site. When considering whether to pursue a parcel of land, a developer will assess physical site conditions (e.g. environmental hazards, topography, utility access) and the regulatory framework that determines what can be built on the site (e.g. zoning). They will assess what kind of housing and how many units could be built. Even at this early stage, they conduct a detailed feasibility analysis to determine whether a project at the location will be sufficiently profitable to proceed. A developer may achieve “site control” by acquiring a parcel outright or through an option contingent on successful permitting. Securing an option on a parcel allows a developer to move forward with relatively little capital at risk as they identify, evaluate, and pursue potential opportunities for a site. In some cases, especially with the disposition of public land for housing, the owner may solicit multiple proposals and select a developer that provides the most advantageous response.

Predevelopment

Predevelopment is all the activity that takes place to get the site ‘shovel ready’ for new homes. This includes site feasibility assessments, architecture and engineering, permitting, contract negotiation, and assembly of project financing. This phase can take less than a year for small projects, those with as-of-right zoning, and/or those on uncomplicated sites. However, for large projects with any degree of complexity, predevelopment takes years. This phase consists of three large and interconnected workstreams:

- Entitlements and permitting. The developer secures the necessary permits from the municipality and the state to construct housing on the site. This may include zoning variances or special permits, wetlands, wastewater disposal, roadway, and building permits, among others. The timeline and impact on feasibility depends on factors including: whether the project can be built by right or needs a special permit, which entity must issue approvals, if any MEPA thresholds are triggered, if the development will use a Comprehensive Permit, neighborhood support or opposition, and legal challenges to permitting decisions.

- Design. An architect works with a team of engineers and other consultants to determine where on a site buildings will be located, what those buildings will look like, and the layout of the units within. The team prepares detailed structural and system designs that are reviewed by local building officials.

- Financing. The developer secures a range of resources to pay for the project. Rental developments must arrange two different types of loans: Short-term construction loans to pay for the work; and long-term permanent mortgages that consolidate all other loans when the project goes into operation. (For-sale projects do not need permanent financing.) Loans will not cover the entire cost; developers must also seek equity investors who have a long-term financial stake in the project. In addition to conventional bank loans and equity investors, developers of affordable housing tap into a range of local, state, and federal subsidies. This allows for long-term affordability, but also entails long waits and laborious processes.

Work throughout this stage is iterative; for example, a change to the unit mix or building design that is requested as part of the permitting process will then impact the design and financing approach. During the predevelopment process, the developer is working “at risk”: if the development does not move forward, they will lose the time and money invested in staff time and consultants. Many pieces of the development puzzle, such as securing financing, finalizing construction drawings, and bidding the project to general contractors, cannot be finalized until entitlements are in place, further stretching out the development timeline.

Construction

Once all permits and financing are secured, construction can commence. There are a wide variety of arrangements for managing the construction. Commonly, a general contractor is selected by the developer and is responsible for mobilizing subcontractors to deliver a completed building. Some developers may “self-contract,” serving as the general manager of all subcontractors and suppliers. Construction timelines vary significantly based on project size and site conditions but can easily be one to two years for moderate or large-scale multifamily projects on complex sites. In addition to managing the physical building construction, during this phase a developer must also prepare for building occupancy. Multifamily housing development is expensive: based on data provided by multifamily residential developers, on average it costs $550,000 per unit for ground-up construction of buildings with 100 or more apartments.

Operations

This is the first stage in a project’s life cycle — typically years after conception — that a project begins to generate revenue. Developers typically begin to market units for sale or lease well before construction is complete. However, depending on building size and market conditions, it can take more than a year for a building to be fully sold or reach full occupancy. After this point, the building is considered “stabilized” and the developer can take the necessary steps to transition to long-term operations. With for-sale developments, this means transferring operational management to the condominium/homeowners’ association. For rental developments, it includes converting construction financing to permanent financing or selling the development to an entity who will hold and maintain it for the long term. Affordable housing may have more services provided, depending on whether the development includes supportive housing. The development will also need to remain compliant with affordability requirements, which may involve income tracking for residents of affordable units, calculation of rents or sale prices to ensure affordability, and coordinating with local, state, or federal governments to prove compliance.

What is development feasibility?

To finance the construction of new homes, developers must demonstrate to lenders and investors that the project is financially feasible: anticipated rents or sales revenue will be sufficient to cover the cost of development and operation and also provide a satisfactory financial return. The analysis of financial feasibility begins early in the housing development process, generally before a site is acquired or optioned. Developers utilize a tool called a pro forma that tabulates development costs, anticipated income, and forecasted operating expenses to estimate net revenue and/or profit. Key variables for each of these items include the following:

Development Costs

- Land acquisition: Acquisition costs vary more than any other piece of the development puzzle: in rural areas of Western and Central Massachusetts, land costs may amount to less than $20,000 per unit, whereas in Metro Boston land costs generally equate to $40,000 - $60,000 per unit. A sample of developments in Metro Boston found that land costs generally constitute 7% - 10% of total development cost

- Soft costs: This category includes surveys, architectural drawings, zoning and environmental permitting, engineering reports, and legal expenses. Survey responses from private sector developers indicate soft costs are in the range of 10 – 12% of total project costs. These can be much higher if a developer faces a lengthy permitting process, must produce multiple revisions of the design, or must address complex engineering issues.

- Hard costs: Actual construction comprises approximately 75% of total development costs for the projects in EOHLC’s survey. This includes general contractors, site work, infrastructure, materials, foundation construction, framing, systems, interior finishes, and landscaping. These costs average $370 per square foot for mid-rise (4-6 stories) wood-frame buildings. Hard costs vary greatly depending on the construction type, location, building height, unit size, and many other variables.

- Impact fees or mitigation: Payments to municipalities or utilities to upgrade infrastructure or provide community benefits. Based on extensive case law, such impact fees can only be used for capital improvements to mitigate impacts exacerbated by the new development.

- Construction insurance: Also known as Builder's Risk Insurance, this is special insurance product that covers a building and its materials while it is under construction. Construction insurance premiums are higher than commercial property insurance for completed buildings since the latter have fully-operational fire detection and sprinkler systems and are occupied which reduces the risk of vandalism.

- Construction loan interest: Developers secure a construction loan to pay for materials and contractors. Interest on this loan accrues during the development period and this debt is then rolled into the permanent financing after project completion. This “capitalized interest” is an average of 4% of total development costs for the projects in EOHLC’s survey. The longer it takes to construct the building, the more interest accrues during that process.

- Developer Fee: Payments to cover the staffing and overhead costs the developer incurs throughout the predevelopment and development phases. This fee accounts for an average of 3% of total development costs in EOHLC’s survey.

Revenue

- Rents or sale prices: These are forecasted during predevelopment but ultimately determined by market conditions at the time of sale or rent

- Rents from deed restricted units: This will depend on the bedroom count and AMI level of the unit

- Permanent operating subsidy: This includes project-based housing vouchers and other ongoing supports.)

- Nonresidential income: Income from commercial space, parking, etc.

Operating Expenses

- Property tax

- Utilities

- Insurance

- Maintenance

- Janitorial services and snow removal

- Fair housing marketing and affordability compliance costs

- Capital reserve funds: money set aside to address expected and unexpected future expenditures

- Resident services

- Supportive services

As each of these variables change—for example, as construction costs decrease or interest rates increase—profitability goes up or down. If the anticipated profitability falls too low, lenders and investors may consider the project too risky or too unprofitable to pursue.

Even if a pro forma shows that a development can turn a profit, there is also considerable uncertainty. Housing development is extremely risky, and the likelihood of unanticipated complications is high. Construction costs keep rising, rent growth may slow down, and rates for utilities and insurance are spiraling upward. Any one of these can hamper a development’s feasibility. Depending on their risk tolerance, developers and their equity investors may see a wide range of returns. Some projects generate significant profit, others barely break even, and some never see it to construction. Developers incorporate contingencies to reflect the unpredictable nature of development, but too many unforeseen complications, from a permit appeal to an increase in interest rates or a change in the price of lumber—could cause a developer, or their investors, to put a project on hold or walk away from it entirely. Anecdotal evidence from interviews with developers highlights that the lengthy discretionary local permitting processes increase the overall risk for housing development in Massachusetts. The higher number of public meetings and board decisions results in more “twists and turns” that impact the development process and diminish feasibility. These challenges affect both for-profit and nonprofit developers, with one difference: delays and escalating costs for nonprofit developers don’t impact a profit margin. Instead, they must be covered by additional subsidy or donations or the project cannot proceed.

What determines land costs?

Land costs are not predetermined and fixed—they are the result of a negotiation between buyer and seller, so they are one of the few items that developers may have options and leverage. Unlike interest rates or legal fees or the cost of building materials, a developer can negotiate a price that they believe will work for a project, or failing that, can decline to purchase the parcel and seek opportunities elsewhere.

One way to value land is to look at comparable sales, if there are enough. Another way is to calculate the “residual cost of land” by running a pro-forma in reverse: starting with the desired return on investment and project idea, then working backwards through income and costs to arrive at the maximum amount one could pay for the land and achieve the desired return.

Rezoning has a complex influence on land costs. Upzoning increases the potential yield on the site and may therefore increase the residual cost of land. If more parcels are zoned for multifamily housing, developers can shop around for the most motivated seller. Some sellers simply have an amount they want to get and a willingness to wait for it.

In developed suburbs and urban areas, most parcels are already in some beneficial or income-generating use on them, whether that’s a single-family home or a commercial development. Undeveloped sites suitable for large-scale housing development are scarce, and underutilized land zoned for dense housing is rare, so sellers of these properties can set high prices knowing they don’t have much competition.

When a developer seeks to acquire multiple adjacent parcels to enable a larger-scale project, there are transaction costs (both time and money) associated with each acquisition, driving up the impact on development costs.

The presence of challenging site conditions that could drive up cost, reduce yield, or necessitate complex permitting and entitlement processes will generally have the effect of driving land costs down. Examples of such conditions include lack of access to centralized sewer, which necessitates onsite wastewater disposal or extensions of sewer systems; proximity to nitrogen-sensitive embayments requiring advanced wastewater disposal; sites with steep slopes, shallow bedrock, contaminated soils, and odd shapes are likely to be more expensive to develop and may reduce the potential yield when compared to an unconstrained site of comparable size.

The cost of permitting

Where current as-of-right zoning doesn’t allow for a given proposal, developers may seek approvals for a project through special permits, variances, or the Comprehensive Permit process. All of these add time and unpredictability to the entitlement phase. Discretionary review processes generally provide local officials and residents with an opportunity to react to a development proposal, request changes, and ultimately approve or reject it. Opposition to a development may result in reduced unit count, which may negatively affect feasibility. Delays can cause developers to miss market cycles, lose out on financing options, or experience cost increases in the project. When discretionary review processes involve public hearings, community opposition can significantly stall a project or even kill it altogether.

Often there may be multiple local boards reviewing a given proposal, and multiple requests for changes to program and design. When a developer provides repeated rounds of substantive revisions in response to community concerns, the result sometimes offers better community benefits, but it always drives up costs in the form of architecture and engineering fees. Local zoning, design, and environmental regulations that set clear, consistent, and achievable standards for development can speed this process while increasing predictability and benefits for both the community and the developer.

The Comprehensive Permit process (aka 40B development) allows developers to circumvent local zoning in municipalities that have not achieved certain housing stock benchmarks (10% of homes on the Subsidized Housing Inventory, and more). For developers pursuing this route, zoning and the discretionary review process are no longer major constraints; but the Comprehensive Permit does require extensive local hearings and often results in long legal battles that stretch out over years before a permit is issued. A 2007 study found that only 55% of proposed 40B developments made it to construction.

Chapter 8 of the Acts of 2021: An Act Creating a Next-Generation Roadmap for Massachusetts Climate Policy applies extra scrutiny to development projects inside of or within one mile of any portion of an Environmental Justice community. Any such project subject to baseline MEPA review (such as those involving more than 100,000 gallons of sewage per day, more than 300 new parking spaces, or any alteration of urban renewal plans and developments), is required to submit an Environmental Impact Report (EIR) in accordance with 301 CMR 11.06(7)(b), in addition to the Environmental Notification Form (ENF) that would necessarily be required. These EIRs must provide advance notification, enhanced public participation, and enhanced analysis of impacts on EJ communities. This process may result in changes that provide greater benefits to the neighborhood, but it may also increase the cost and delay the delivery of development consistent with already-established community goals for housing.

Where do developers get their financing?

During the predevelopment phase, developers must assemble the project’s financing. All multifamily market-rate and affordable housing developments obtain a commercial mortgage from a bank—a long-term loan with fixed payments that uses the property as collateral. For market-rate projects, loans often comprise around 65% of the total project funding, whereas affordable housing developers use conventional loans for only 25% of total project funding. All-affordable developments don’t generate enough income to repay a loan that covers a majority of development costs, so they must rely on sources that don’t require repayment.

Development financing also requires equity investments that are essentially an ownership stake in the development. For small projects by local developers, the equity may come from the developer’s own resources. Very few market-rate developers have enough cash on hand to cover 35% of development costs for projects of a significant scale. For example, a 200-unit market-rate development with a development cost of $500,000 per unit requires $35 million of equity investment that is paired with $65 million of loan funding. For deals at this scale or larger, a developer must pitch their project to regional or even national investment teams. This equity investment is not secured by any rights to the property (as the mortgage is) so equity investors assume substantial risk in project development, meaning that they stand a greater chance of losing their investment should anything go awry, and they may experience low returns if the rent and sale prices fall below expectations. Accordingly, they require higher returns than the interest that a bank would charge for a conventional mortgage.

For the most part, financing terms are set by the mortgage lender and the project’s equity investors, not the developer. EOHLC focus groups with industry representatives revealed that major equity investors are seeking a financial return that, after accounting for the risk involved in the development, is comfortably above the return for a reliably safe investment such as a ten-year treasury bond. If forecasts show the development can’t meet that rate of return given current assumptions about construction costs, operating costs, or rental income, then equity investors may choose to invest elsewhere. That means the development can’t get built unless the financial picture improves, or the developer can find another source of equity with lower return expectations.

Interest rates have an enormous impact on project viability. Even a change as small as a tenth of a percent can result in a shortfall (or surplus) of millions of dollars. In a period of rising or volatile interest rates, a years-long entitlements period can substantially change a project’s financial outlook even if rents and construction costs are constant.

Many banks and investors require developers to assume a certain developer fee, so that if costs unexpectedly increase beyond project contingencies, the shortfall will come out of the developer fee before the banks or investors’ returns are impacted.

How is affordable housing financed?

Rents and sales prices of affordable units are generally not sufficient to cover the cost of building and operating a development. In buildings subject to inclusionary zoning, the market rate-units generally offset the lost income from the affordable units. But for all-affordable units or mixed-income developments with deeper affordability, external resources are needed to close the gap. The greater the number of affordable units or the depth of affordability, the more resources are needed; a fully affordable housing development might utilize resources from more than ten different federal, state, local, and private sources.

A typical affordable rental project will include funds from most, if not all, of the following sources, each of which have their own program and documentation requirements.

- Federal Low Income Housing Tax Credits (LIHTC) (federal tax credits administered at the state level). These programs allow investors to make equity investments in affordable housing development in exchange for credits that reduce their tax obligation. Massachusetts gets a certain amount of these tax credits and EOHLC allocates them to developments. Federal LIHTC typically comprises the largest share of the subsidy in an affordable housing development. They are highly competitive, and developers typically must apply in at least two annual funding cycles before they are awarded funds. Because of per-unit caps and other restrictions, tax credits are most effective in mid-sized projects of 40-60 units.

There are two forms of federal tax credits: a so-called 9% credit which is competitively awarded by EOHLC; and a 4% credit which is available to all projects that meet certain requirements. 9% credits typically take a long time to apply for and receive – a developer may have to apply multiple times for the same project. The 9% credit raises around 70 percent of a project’s equity, while the 4% credit raises roughly 30 percent of the equity. A single project cannot receive both; as a result, developers will break a development into two different “deals,” each of which comprises a different set of buildings or even different floors within the same building. - State LIHTC: Massachusetts’ state LIHTC program is modeled after the federal 9% credit to supplement the low supply of federal credits. The credit applies for state tax liability only and is valid for 5 years rather than 10 years. State LIHTC-funded projects must be affordable to households with 60 percent AMI or less. Generally, the credit covers ~10% of funding for an affordable housing project. Governor Healey increased state LIHTC through the 2023 tax relief bill.

- State housing subsidies: EOHLC and its quasi-public partners (MassHousing, CEDAC, MHP) make capital funds available for affordable housing development through a variety of financial products and subsidies. Many of these are so-called “soft debt”: loans with minimal repayment requirements and loan forgiveness after a specified period of time. The most significant programs are the Massachusetts Affordable Housing Trust, the Housing Stabilization Fund, and the state’s allocation of federal HOME funds. The legislature has also created certain bonding authorizations intended to support specific populations. These funding programs include the Housing Innovations Fund, Facilities Consolidation Fund, and the Community-Based Housing Program. Target populations include veterans, formerly homeless individuals, seniors, or clients of the Department of Developmental Services. There are also specific bonding authorizations related to transit-oriented development, climate resilience, and other purposes. EOHLC administers more than a dozen separate loan programs, and almost every project receives funding from multiple EOHLC sources. The Affordable Homes Act authorized record levels of capital investment in these programs.

- Project-based vouchers: EOHLC and Local Housing Authorities assign some mobile vouchers to specific subsidized housing developments to create units with deeper affordability than would be possible with tax credits and soft debt alone. By doubling up the affordability provided by tax credits and soft debt with ongoing subsidy in the form of a rental voucher this is a key tool to enable deep affordability in tax credit projects.

- Home Investment Partnerships (HOME) Program (federal, administered locally or regionally). Municipalities above a certain population receive their own allocation of federal HOME funds, while smaller municipalities may join a multi-municipal consortium that receives and administers federal HOME funds for member municipalities.

- Affordable Housing Trust Fund (local). Municipal Affordable Housing Trust Funds are enabled by state legislation for the purpose of collecting and utilizing funds for local initiatives to create and preserve affordable housing.

- Community Preservation Act (CPA) Funds (local). The Massachusetts CPA law allows municipalities to collect funds for public investments in specific categories, including affordable housing, through a property tax surcharge and matching state funds. While the CPA requires that municipalities dedicate at least 10% of their CPA funds to housing, a 2023 report prepared by the Center for State Policy and Analysis found that 70 municipalities have failed to hit the 10% benchmark.

Public funding is constrained and competitive. Applying for sources like 9% LIHTC, state soft debt, and local sources can take multiple years and can be denied at the first application. Even with subsidies, funding constraints can lead to decisions that aren’t ideal, like breaking projects into multiple phases. LIHTC increases transaction costs by slowing down development, necessitating a large amount of legal work, and requiring careful work throughout the development process to make sure a development complies with regulations. For this reason, small projects generally cannot use LIHTC funds because the increased soft costs are more than the subsidy. To be eligible for federal LIHTC, developments must have: a) 20 percent of units affordable to households at 50 percent of AMI; b) 40 percent of units affordable to households at 60 percent of AMI; or c) 40 percent of units affordable to households at an average of 60 percent of AMI, with all affordable units targeted to households at or below 80 percent AMI.

Combining funding streams from multiple of these sources takes far longer than a conventional project that might require only two or three private sources, increasing carrying and staffing costs and increasing the risk of a change in interest rates or construction costs. Applying for and administering this array of public and private sources also takes a substantial amount of time and legal assistance, and may involve requirements on use or service provision, which could further drive up costs. These costs are difficult to quantify, but the Terner Center estimates that each additional funding source is associated with a cost increase of roughly 1.7 percent per unit, or a 10 percent increase in soft costs. This can quickly add up to several hundred thousand dollars for projects that require five or more funding sources.

Most funding sources require entitlements to be in place before a project can be considered eligible for an award. Since the application process itself can take years, this further extends the predevelopment timeline and associated costs.

As challenging as it is for any developer to acquire land, mission-based affordable housing developers face additional challenges. The first is availability of liquid capital: land deals often happen quickly, and affordable housing developers rarely have the cash on hand to make a quick offer. Even if they do, limited resources make it difficult for affordable housing developers to compete with offers from market-rate developers who have the capacity to take risks on a site. Because of this, affordable housing developers often acquire more difficult-to-develop sites that see less competition from market-rate developers. State housing agencies have worked to address this through programs like MassHousing’s BILD (Bringing Innovation to Lending and Development) program and the $50M investment in the Momentum Fund included in the 2024 Affordable Homes Act. The Affordable Housing Overlay in Cambridge sought to level the playing field by allowing affordable developments to exceed zoning height limits and thereby spread the land cost over more units, and the pipeline of projects using the AHO includes nearly 1,000 total units as of August 2025.

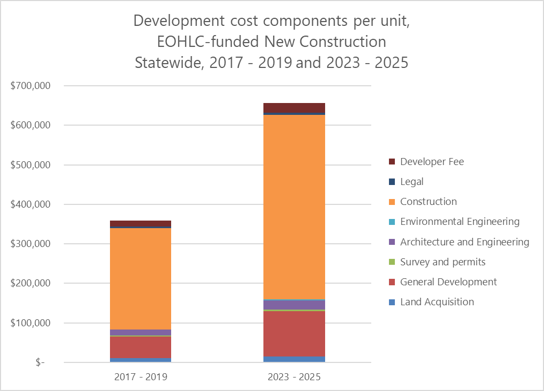

As a result of all these factors, total development cost per unit for EOHLC-funded new construction statewide exceeded $650,000 in 2024. This is due to a variety of factors including longer permitting timelines, more complicated funding streams, labor requirements, energy efficiency standards. Due to the complexity of working in older, existing buildings, the costs of adaptive reuse are comparable to new construction.

Per-unit development costs for EOHLC-funded developments rose 78% over a six-year period, driven by increases in construction (up 82%) and 'general development' costs (up 110%).

What’s the impact of sustainable building requirements?

Massachusetts has been rapidly adopting efficiency, decarbonization, and resiliency policies that require changes in building design and construction practices. The importance of these policies for a sustainable future is incontrovertible, but their impact on construction cost and overall production is unclear. Evidence on the impact of energy efficiency requirements varies by source, time period, type of project, and type of requirement. When surveyed, developers often cite a 5-10% cost premium to reach net-zero. Some general contractors estimate a cost premium as high as 15%, whereas many architects estimate a more optimistic 2-3% premium. The Massachusetts Green Energy Center Passive House Design Competition achieved passive house standards with under a 3% incremental cost, and data collected in 2020 – 2021 by the North American Passive House Network shows incremental costs of 1-8% for building passive houses.

It's understandable that new standards may increase complexity and costs, at first. Adopting passive house standards requires builders to become experts in new building code applications, new certification processes, and new materials and appliances. Local governments are sometimes unfamiliar with green building materials, practices, and appliances, further slowing down construction as code enforcement relies on officers who must learn about materials and practices before certifying compliance. As time passes and more energy-efficient residences are constructed, builders and other actors in the development process gain experience and costs fall. Developers learn more about the design process for energy-efficient homes, reducing the need to fix problems during construction caused by mistakes in design.

Some developers report that adapting a project’s design to meet current building and energy codes is challenging and costly, given the timeframe of the entitlement period. Given the long lag between when design is complete and all entitlements are finalized, building and energy codes can change and come into effect before a building permit can be applied for, which creates the need for costly redesigns, early release of equipment, and updates to critical infrastructure to meet new code requirements. These designs can sometimes impact the overall project (unit count, etc.), which can cause a circular re-permitting effort.

What’s the impact of inclusionary zoning?

Inclusionary zoning (IZ) is a tool to produce deed restricted units without public subsidy. IZ requires developers to set aside a portion of units for low-income households, usually at 50% - 80% AMI, in exchange for variances, density bonuses, parking reductions, or other relaxations of zoning regulations. The creation of inclusionary units has little to no direct impact on the construction cost of the development, since deed restricted units must be effectively identical to the market rate units. The financial difference emerges during operation, since the inclusionary units produce less income than do the market rate units. Over time and for developments with higher-priced apartments, this discount can add up to a significant reduction in projected revenue. If affordability standards are set too high, the rents from the market-rate units might not be sufficient to offset the lost income and meet investor expectations, and the development becomes financially infeasible.

How does parking affect feasibility & affordability?

Parking spaces are expensive to build—as much as $40,000 per space for ground floor parking and $15,000 for surface parking. It is also expensive to maintain, up to $800 per space per year for covered parking, and $200 per space per year for surface parking. The cost of building and maintaining that parking is passed directly onto residents in sales or rent prices. Moreover, parking often takes up space that could otherwise be occupied by additional residential units. Almost a third of parking spaces in recently developed multifamily development go unused. Reducing or eliminating minimum parking requirements may reduce construction costs and allows for higher unit yield at many sites, improving development feasibility.

Because parking is so expensive to build, direct parking fees don’t make parking construction break even. Therefore, some portion of the cost of parking is written into sales price/rents, leading car-free residents of multifamily buildings to subsidize parking spaces for those who have cars.

How much does labor cost?

Wage rates are a major component of the construction budget. Many developers choose union labor which provides high quality construction, but at a cost premium relative to comparable nonunion workers. Many public funding sources in Massachusetts are subject to prevailing wage requirements, which sets a minimum wage for each class of laborers and mechanics in a certain geographic area. Projects built on municipally-owned land or on land owned by a local housing authority are subject to prevailing wage restrictions.

A 2024 Terner Center study found that in California in 2020 to 2023, LIHTC developments cost an estimated $94,000 more per unit to build if they planned to use prevailing wages. However, some studies have found that union labor is more productive than non-union labor, sometimes eliminating differences in total construction costs between union and non-union labor.

Density and dimensional regulations

Dimensional regulations such as allowable density or FAR, setbacks, or building height limit the scale or design of a project, so they limit the total scale of a potential project. Generally, larger developments of a given type have lower per-unit costs because fixed costs can be spread out over more units. For example, a height limit of 60 feet might allow for a five-story building, whereas an additional 5 feet of height could allow a sixth story, increasing the number of units by 20% or more without substantial changes in soft costs, acquisition, or site work/infrastructure. That difference in revenue could determine the financial feasibility of a development. Minimum parking requirements also reduce unit yield and drive up construction costs; and surveys have shown that a quarter of this parking generally goes unused. For affordable developments, LIHTC, bond financing, and mortgages all have high overhead due to legal, accounting, consulting, and other fees, pushing up fixed costs for publicly funded housing in particular.

Hard costs also vary by building height. Buildings of 6 stories or below can use wood frame construction (often referred to as 5-over-1). At 7 stories or higher, building codes require steel construction throughout, which is much more expensive than wood-frame construction. As a result, there is a very high marginal cost for the 7th floor. For that reason, developers rarely move forward with 7-story projects and will prefer to either build a 6-story building or to build 10 stories or higher. Where land costs are low, it may be cheaper to build a large but short project by expanding horizontally. In areas with high land costs, developers are more likely to want to build vertically to increase project size.