- Scientific name: Catostomus catostomus

- Species of Greatest Conservation Need (MA State Wildlife Action Plan)

- Special Concern (MA Endangered Species Act)

Description

Longnose sucker (Catostomus catostomus)

Longnose suckers are torpedo-shaped fish with a snout that extends beyond the subterminal mouth. They can grow to over 500 mm (~20 in); however, in New England they are generally smaller and reach lengths of 300-400 mm (12-15 in). They are silvery-gray to yellowish in color and sometimes have darker blotches or saddles along their sides. During the breeding season mature individuals have a red lateral stripe and tubercles on their head and fins.

Longnose suckers and white suckers (Catostomus commersoni) can be easily confused. Longnose suckers have finer scales and have >85 lateral line scales, compared to <75 for white suckers. This characteristic has lead to one of their alternate common names the finescale sucker. The lateral line pores can sometimes be easily seen in the longnose sucker whereas in the white sucker the pores are not visible. The distance between the edge of the snout and the leading edge of the upper lip is noticeably longer in longnose sucker compared to white sucker. Also, longnose sucker’s lower lips look like two square flaps, whereas in the white sucker, the lower lips are more tapered.

Life cycle and behavior

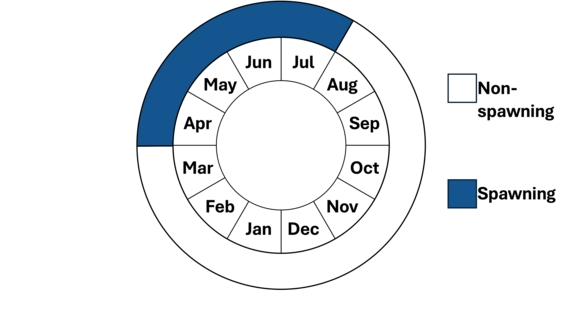

Longnose suckers grow slowly and start spawning at 5-7 years (Harris 1962, Geen et al. 1966). The species has a relatively long lifespan reaching up to ~20 years (Scott and Crossman 1973), with adults spawning multiple times (Geen et al. 1966). Spawning migrations occur from mid-April to July (Scott and Crossman 1973, Montgomery et al. 1983) after water temps reach 5° C (41°F and/or after peak high water (Geen et al. 1966, Barton 1980, Montgomery et al. 1983). Peak spawning is short, lasting between 5-10 days (Montgomery et al. 1983). Spawning is often in currents of 30-45 cm/s (0.98–1.48 ft/s) and over gravel substrates 5-100 mm (0.2-3.9 in) diameter (Geen et al. 1966). Longnose suckers do not make nests but release adhesive, demersal eggs (Scott and Crossman 1973). Eggs hatch after 8-14 days and young-of-year can be found in midwater feeding on plankton with their terminal mouths which becomes subterminal as they grow. Adult longnose suckers feed primarily on benthic invertebrates, specifically Gammarus, Daphnia, and a variety of insect larvae as well as algae. Longnose suckers are vulnerable to predation during spawning by a variety of animals, such as chain pickerel, black bears and other mammals, and ospreys.

Population status

The longnose sucker is listed as special concern in Massachusetts. As with all species listed in Massachusetts, individuals of the species are protected from take (collecting, killing, etc.) and sale under the Massachusetts Endangered Species Act.

Distribution and abundance

White sucker (top) and longnose sucker (bottom) can co-occur in streams and identification can be difficult. The more numerous lateral line scales in longnose sucker are clear from these similar-sized individuals.

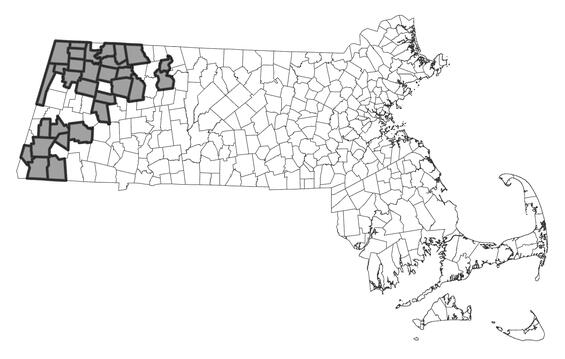

The longnose sucker range extends from Alaska and Canada south to Colorado, east to the Great Lakes region and into the northeast region. In New England, longnose sucker occurs in Massachusetts, Vermont, New Hampshire, and Maine. In Massachusetts, the species occurs in the Hoosic, Housatonic, Deerfield, Westfield, and Middle Connecticut River watersheds. Massachusetts represents the species most southeastern distribution in its range. The most viable populations are represented in the Deerfield, Hoosic, and Housatonic watersheds; however, these populations are fragmented by dams, and exposed to altered streamflows, stream bank hardening, agricultural and industrial runoff and discharge. Longnose suckers once apparently occupied the mainstem Connecticut River and the lower Westfield River, but the range has likely contracted because of water quality degradation and habitat loss. The species has only been recorded in a few smaller tributaries in the Middle Connecticut River watershed.

Distribution in Massachusetts. 2000-2025. Based on records in the Natural Heritage Database.

Habitat

In Massachusetts, longnose suckers are characterized as a fluvial specialist found mainly in clear, cold-water small to medium-sized streams of low to moderate gradient and well-oxygenated water. Substrates are typically dominated by clean gravel and cobble. In other parts of their range they are also found in lakes including the Great Lakes. Overwintering habitat is likely in low-velocity habitats, such as deep pools, backwaters, or under woody debris (Cunjak 1996).

Healthy habitats are vital for supporting native wildlife and plants. Explore habitats and learn about conservation and restoration in Massachusetts.

Longnose sucker habitat from small to larger-sized streams (left to right).

Threats

Habitat alteration is a major threat, especially through erosion and sedimentation, flow alterations, industrial discharge, agricultural runoff, road salts, loss of riparian vegetation, and increased water temperatures from climate change. This species relies on clean, well-oxygenated gravel substrates for their eggs to develop and these threats can severely decrease their reproductive success. In addition, dams can prevent their migration to preferred spawning habitats and reduce population connectivity.

Conservation

Longnose suckers are monitored through routine fish community surveys, which are successful at detecting the species in its riverine habitat.

Management

Management for this species focuses on habitat protection and restoration such as improvements to streamflow, dam removal, culvert replacement, and riparian and streambank restoration. Protection of forested riparian zones and watersheds is critical for maintaining high water quality and cooler water temperatures.

Research needs

Effort is needed to establish long-term monitoring sites to detect temporal trends in population size, survey new and historical sites, determine spawning sites and refine spawning date range, determine potential seasonal migration behavior, identify potential dispersal barriers, determine population genetic structure and variation to determine gene flow and compare with more northernly core populations, evaluation of critical swimming thresholds to inform dam and culvert design, and assess the species risk to climate change impacts including increased stream temperature and extreme flows.

References

Barton, B.A. 1980. Spawning migrations, age and growth, and summer feeding of white and longnose suckers in an irrigation reservoir. Canadian Field Naturalist 94(3): 300-304.

Brown, R.S., G. Power, and S. Beltaos. 2001. Winter movements and habitat use of riverine brown trout, white sucker and common carp in relation to flooding and ice break-up. Journal of Fish Biology 59:1126-1141. (A01BRO02MAUS)

Cunjak, R.A. 1996. Winter habitat of selected stream fishes and potential impacts from land-use activity. Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 53(Supplement 1):267-282. (A96CUN01MAUS)

Geen, G. H., et al. 1966. Life histories of two spp. of catasotmid fishes in Sixteenmile Lake, B. C., with particular ref. to inlet stream spawning. J. Fish. Res. Board Can. 23(11): 1761-1788.

Harris, R.H.D. 1962. Growth and Reproduction of the longnose sucker, Catostomus catostomus in Great Slave Lake. Journal Fisheries Research Board of Canada. 19(1): 113-126.

Hartel, K.E., D.B. Halliwell, A.E. Launer. 2002. Inland fishes of Massachusetts. Massachusetts Audubon Society. Lincoln, MA.

Montgomery, W.L., S.D. McCormick, R.J. Naiman, F.G. Whoriskey, and G.A. Black. 1983. Spring migratory synchrony of salmonid, catostomid, and cyprinid fishes in Riviere a la Truite, Quebec. Canadian Journal of Zoology 61:2495-2502.

Scott, W. B. and E.J. Crossman. 1973. Freshwater fishes of Canada. Fisheries Research Board of Canada Bulletin 184, 966 pp.

Contact

| Date published: | April 10, 2025 |

|---|