- Scientific name: Enallagma laterale

Species of Greatest Conservation Need (MA State Wildlife Action Plan)

Description

Male New England bluet

The New England bluet is a small, semiaquatic insect of the order Odonata, suborder Zygoptera (the damselflies), and family Coenagrionidae (pond damsels). Like most damselflies, New England bluets have large eyes on the sides of the head, short antennae, and four heavily veined wings that are held folded together over the back. The male’s thorax (winged and legged section behind the head) is mostly blue with black stripes on the “shoulders” and top. The New England bluet has a long, slender abdomen composed of ten segments. The abdominal segments are blue with black markings on segments 1 through 7. Segments 1 through 5 are mostly blue and segments 6 and 7 are almost entirely black on top. Segments 8 and 9 are entirely blue, except segment 8 has a horizontal black dash on each side of the segment. This mark is always present but varies greatly in size. The top of segment 10 is black. Females have thicker abdomens than the males, and are generally brown where the males are blue, though older females may become quite blueish. New England bluets average 25-28 mm (just over 1 in) in length.

The bluets (genus Enallagma) comprise a large group of damselflies, with more than 20 species in Massachusetts. Identification of the various species can be very difficult and often requires close examination of the terminal appendages on the males (Nikula et al. 2007) or the mesostigmal plates (located behind the head) on the females (Westfall & May 1996). The New England bluet is most similar in appearance to the pine barrens bluet (E. recurvatum), a Threatened species in Massachusetts. Both species are found in coastal plain ponds and co-occur together with similar flight periods. The two species are most safely distinguished by the shape of the terminal appendages on the male and the mesostigmal plates of the females. The black dash on the sides of segment 8 is generally larger in the New England bluet; however, this feature is highly variable and should not be used for definitive identification.

Life cycle and behavior

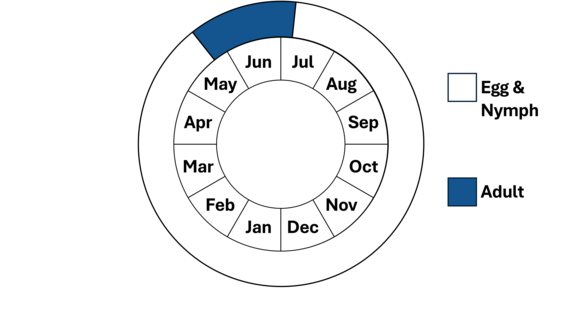

Note adult life stage is synonymous with fight period.

Although little has been published specifically on the life history of the New England bluet, it is likely similar to other, better-studied species in the genus. All odonates have three life stages: egg, aquatic nymph, and flying adult. The nymphs are slender with three leaf-like appendages extending from the end of the body which serve as breathing gills. They have a large, hinged lower jaw which they can extend forward with lightning speed. This feature is used to catch prey, the nymph typically lying in wait until potential prey passes within striking range. They feed on a wide variety of aquatic life, including insects and worms. They spend most of their time clinging to submerged vegetation or other objects, moving infrequently. They transport themselves primarily by walking, but are also capable of swimming with a sinuous, snake-like motion.

New England bluets have a one-year life cycle. The eggs are laid in the early summer and probably hatch in the fall. The nymphs develop over the winter and spring, undergoing several molts. In early to mid-summer the nymphs crawl out of the water up onto emergent vegetation and transform into adults. This process, known as emergence, typically takes a couple of hours, after which the newly emerged adults (tenerals) fly weakly off to upland areas where they spend a week or two feeding and maturing. The young adults are very susceptible to predators, particularly birds, ants, and spiders; mortality is high during this stage of the life cycle. The adults feed on a wide variety of smaller insects which they typically catch in flight.

When mature, the males return to the wetlands where they spend most of their time searching for females. When a male locates a female, he attempts to grasp her behind the head with the terminal appendages at the end of his abdomen. If the female is receptive, she allows the male to grasp her, then curls the end of her abdomen up to the base of the male’s abdomen where his secondary sexual organs (“hamules”) are located. This coupling results in the heart-shaped tandem formation characteristic of all odonates. This coupling lasts for a few minutes to an hour or more. The pair generally remains stationary during this mating but, amazingly, can fly, albeit weakly, while coupled.

Once mating is complete, the female begins laying eggs (oviposits) in emergent grasses and rushes, and floating-leaved plants by using the ovipositor located on the underside of her abdomen to slice into the vegetation to deposit eggs. Although the female occasionally oviposits alone, in most cases the male remains attached to the back of the female’s head. This form of mate-guarding is thought to prevent other males from mating with the female before she completes egg-laying. The adult’s activities are almost exclusively limited to feeding and reproduction, and their life is short, probably averaging only three to four weeks for damselflies like the New England bluet. The flight season of the New England bluet is somewhat longer than that of the closely related pine barrens bluet, although most records are also restricted to the month of June. Emergence generally occurs during the last week of May and adults can be seen into early July.

Distribution and abundance

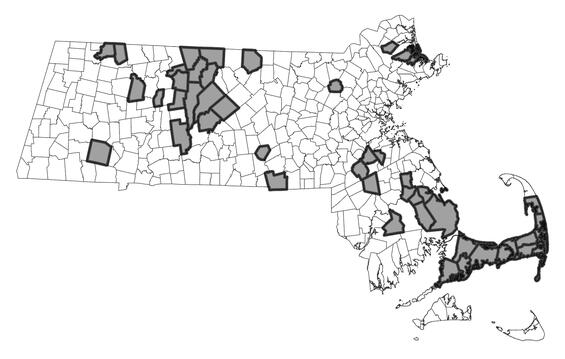

The New England bluet is a regional endemic and has a range restricted to scattered locations in the northeastern United States, from southwestern New Brunswick to New Jersey and Pennsylvania. In New England they have been found in every state but are most common from eastern Massachusetts southwestward to Connecticut. In Massachusetts, the species occurs in Deerfield, Westfield, Middle Connecticut, Millers, Nashua, Concord, Parker, Ipswich, Blackstone, Neponset, Taunton, and Cape Cod with most observations from the southeast.

This species was once considered rare in the state, detected only on the southeastern coastal plain. With more sampling effort over the past 30 years, new and apparently viable sites have been observed across Massachusetts leading to its delisting under the Massachusetts Endangered Species Act. The species has undergone a possible range expansion within the northeast (Hunt 2012, Butler et al. 2019) including into sites in central and western Massachusetts, although survey effort has not been consistent.

Distribution in Massachusetts.

1999-2024

Based on records in iNaturalist, Odonata Central, and Natural Heritage databases.

Habitat

New England bluets have been found in a variety of acidic lentic habitats with moderate to abundant emergent and floating aquatic vegetation. Occupied wetlands include swampy open water in north-central Massachusetts, impoundments, and sandy coastal plain ponds where they are most common. These systems tend to have high shoreline and littoral habitat integrity (i.e., limited shoreline development) (Butler and deMaynadier 2008). The species is closely associated with floating-leaved aquatic vegetation including Brasenia, Nymphaea, and Nuphar (Gibbons et al. 2002, Butler and deMaynadier 2008). The nymphs are aquatic and live among aquatic vegetation and debris. The adults inhabit emergent vegetation in wetlands and fields and forest near wetlands.

Healthy habitats are vital for supporting native wildlife and plants. Explore habitats and learn about conservation and restoration in Massachusetts.

Coastal plain pond habitat with an abundance of floating-leaved and emergent vegetation.

Threats

The major threats to New England bluet are shoreline and wetland degradation and loss. Shoreline development may eliminate nearshore/littoral zone and riparian vegetation and harden shorelines through construction of buildings, roads, and other human constructions. Further, shoreline development facilitates increased nutrient and contaminant inputs (e.g., road salts, septic, fertilizer), sedimentation, surface and groundwater withdrawals or water level alteration (e.g., winter drawdown), pesticide use, introduction and spread of invasive species (aquatic vegetation and animals), and recreational activity (e.g., off-road vehicles, boat wakes). These activities lead to wetland/pond degradation that accelerates eutrophication, degrades water quality, and alters or eliminates aquatic vegetation composition required for New England bluet including floating-leaved vegetation. Invasive species including Phragmites can replace native vegetation creating unsuitable habitat conditions for New England bluet. In addition, climate change may create unfavorable conditions, including prolonged drought and high-water events, that in combination with ongoing habitat degradation (water withdrawals, nutrient inputs) can increase cyanobacteria blooms, reduce habitat, and alter aquatic vegetation composition unsuitable for the species. Since this species occasionally occupies impoundments, unmanaged dam removals may locally extirpate the species from sudden dewatering and habitat loss. High-impact recreational use, such as off-road vehicles driving through pond shores which may destroy breeding and nymphal habitat, and motorboats whose wakes swamp delicate emerging adults, are also threats. Since New England bluets, spend a period of several days or more away from the pond maturing, it is important to maintain natural upland habitats adjoining the breeding sites for roosting and hunting. Without protected uplands the delicate newly emerged adults are more susceptible to predation and mortality from inclement weather (Hunt et al. 2020).

Conservation

Survey and monitoring

Since New England bluet is a regional endemic species and has clear association with relatively intact undisturbed shoreline habitat, tracking this species remains important for species and habitat conservation. This species should be recorded when targeting associated state-listed damselfly species including E. pictum, E. recurvatum, and E. daeckii. Standardized surveys should target known sites and new wetlands to determine New England bluet occupancy and population status. Surveys for adults are likely to be more effective for detection compared to nymph or exuvia as this life stage is extremely difficult to find and identify. Adult surveys should target nearshore, open-water, and riparian habitats during their flight period during standardized weather and time windows to maximize species detection. Multiple site visits (e.g., ≥3) are likely required to detect this species because of its typical low abundances and ephemerality. Effort should also be devoted to surveys at potential suitable sites to document potential range expansion (e.g., western MA) and update the species distribution and status in the state.

Management

Protection and restoration of shoreline/littoral zone, riparian, and upland habitat is critical for New England bluet persistence in Massachusetts. Actions that can improve or prevent habitat degradation include: reduction of nutrient, agricultural and road runoff; minimization of water level alteration that impacts native aquatic vegetation; minimization of groundwater withdrawals particularly during drought periods; prevention and management of nonnative aquatic vegetation species; development of best practices for herbicide use; limitation and enforcement of off-road vehicles on shoreline habitat; management of dam removals to mitigate for potential habitat and population loss; and connection between ponds and other pond complexes.

Research needs

Research effort is needed to estimate detection and occupancy rates and how other environmental variables (e.g., sample timing, weather) affect these rates. Identification of source and sink wetland sites and general population dynamics within and across pond complexes is needed in Massachusetts to prioritize site conservation. Other needed research efforts include estimation of physiological tolerances to insecticides and herbicides; impacts of non-native fish and aquatic vegetation on populations; and projections of species distribution under climate change scenarios and climate vulnerability analysis.

References

Brown, V.A. 2020. Dragonflies and Damselflies of Rhode Island. Rhode Island Division of Fish and Wildlife, Department of Environmental Management, West Kingston RI.

Butler, R.G., H. Mealey, E. Kelly, A. St. Pierre, L. Wadleigh, and P.G. deMaynadier. 2019. Status, Distribution, and Conservation Planning for Endemic Damselflies of the Northeast: Maine. Report to Maine Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife. University of Maine, Farmington.

Gibbons, L.K., J.M. Reed, and F.S. Chew. 2002. Habitat requirements and local persistence of three damselfly species (odonata: coenagrionidae). Journal of Insect Conservation 6:47-55.

Hunt, P.D. 2012. The New Hampshire Dragonfly Survey: A Final Report. Report to the New Hampshire Fish and Game Department, New Hampshire Audubon, Concord.

Hunt, P. 2020. Conservation planning for endemic damselflies of the northeast: A report to the Sarah K. deCoizart Article TENTH Perpetual Charitable Trust. Concord, NH. 18 p.

Hunt, P., V. Brown, R. Butler, P. deMaynadier, L. Harper, L. Saucier, R. Somes, E. White. 2020. A conservation plan for the endemic damselflies of the northeast. 20 p.

Lam, E. 2004. Damselflies of the northeast. Biodiversity Books, Forest Hills, New York, 96 p.

McAlpine, D.F., H.S. Makepeace, D.L. Sabine, P.M. Brunelle, J. Bell, and G. Taylor. 2017. First occurrence of Enallagma pictum (Scarlet bluet) (Ononata: Coenagrionidae) in Canada and additional records of Celithemis martha (Martha’s Pennant) (Odonata: Libellulidae) in New Brunswick: possible climate-change induced range extensions of Atlantic Coastal Plain Odonata. J. Acad. Entomol. Soc. 13: 49-53.

Nikula, B. 2019. A survey for five species of Enallagma (bluet) damselflies in southeastern Massachusetts. Report to Natural Heritage and Endangered Species Program, Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife, Westborough, MA.

Nikula, B., J.L. Ryan, and M.R. Burne. 2007. A Field Guide to the Dragonflies and Damselflies of Massachusetts. Massachusetts Natural Heritage and Endangered Species Program.

Walker, E.M. 1953. The Odonata of Canada and Alaska, Vol. I. University of Toronto Press.

Westfall, M.J., Jr., and M.L. May. 1996. Damselflies of North America. Scientific Publishers.

Contact

| Date published: | April 7, 2025 |

|---|