- Scientific name: Glaucomys sabrinus

Species of Greatest Conservation Need (MA State Wildlife Action Plan)

Description

Northern flying squirrel

Northern flying squirrels have large black eyes and thick, soft fur with a rich brown-gray color above and white below. They have belly fur that is white at the tips and gray at the base to the skin. The tail is dark brown above and white below with a flattened appearance. A membrane or folded layer of loose skin exists between their forelegs and hindlegs, giving them the ability to glide through the air between trees. They have been known to cover more than 45 m (150 ft) in a single glide. Northern flying squirrels are slightly larger than the southern flying squirrel at 25-30 cm (10-12 in) in length.

Similar species: The northern flying squirrel is larger on average than the southern flying squirrel (Glaucomys volans, 20-25 cm [8 to 10 inches] in length). The belly fur of northern flying squirrel is white at the tips and gray at the base to the skin, distinguishing it from southern flying squirrel, which has white belly fur throughout.

Life cycle and behavior

Northern flying squirrels are nocturnal and highly arboreal, spending most of their lives in trees. Unlike other squirrels, they do not jump from tree to tree but instead glide using a patagium, a membrane stretching between their limbs. They can control their glides with their tail and limbs, making mid-air adjustments to land on tree trunks (Wells-Gosling & Heaney 1984).

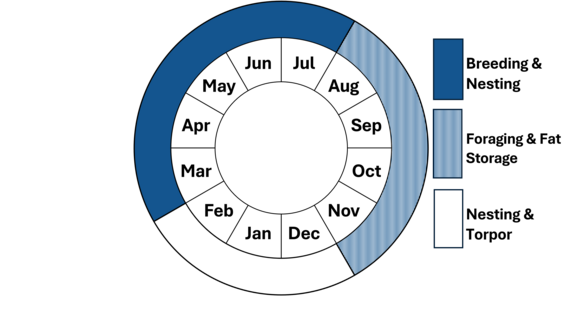

These squirrels do not hibernate but may enter torpor during extreme cold periods. They nest in tree cavities, abandoned bird nests, or leaf nests. They are social creatures, sometimes sharing nests with other flying squirrels to conserve body heat in winter.

Breeding occurs in late winter or early spring, with one litter of 2-4 young per year. The young are born blind and helpless, relying on their mother for warmth and food. They begin to glide at about 6 weeks old and are independent at around 3 months (Weigl 2007).

Population status

The northern flying squirrel was listed as a Species of Greatest Conservation Need (SGCN) in Massachusetts during the 2015 update to the Massachusetts State Wildlife Action Plan (SWAP). This plan identified 570 species, including the northern flying squirrel, as requiring conservation attention. The species has likely experienced range contraction due to habitat loss and competition with the expanding population of the southern flying squirrel (Weigl 2007).

Their population is stable in other parts of their range, particularly in mature boreal and coniferous forests of the northern U.S. and Canada. However, the species is highly sensitive to forest fragmentation and climate change (Iverson & Prasad 2001).

Distribution and abundance

Northern flying squirrels may still occur in northern portions of Massachusetts but have not been confirmed in over 60 years. The current distribution of the species in Massachusetts is unclear. Massachusetts is considered the southernmost limit of the low elevation portion of the northern flying squirrel range. Its range continues farther south at higher elevations, terminating in a few isolated mountaintop populations in the southern Appalachian Mountains of North Carolina and Tennessee. The last preserved specimen from Massachusetts was from Northampton, Hampshire County in 1964. There have been a few more recent reports of northern flying squirrels, but without documentation. Unfortunately, since the southern flying squirrel has spread and is now common statewide, except for the islands, it is not possible to know which species was seen without good photos or a specimen. The northern flying squirrel probably does still occur in Massachusetts but is probably restricted to the northern tier of the state in Franklin and northern Berkshire counties.

Habitat

A gliding northern flying squirrel.

Northern flying squirrels prefer mature coniferous and mixed forests with old dead trees that provide nesting holes. They live in snags, woodpecker holes, nest boxes, and abandoned bird or squirrel nests. Their diet includes a wide variety of plant and animal items, but a large portion of their diet includes fungi and lichens, especially truffles (Weigl 2007). They are often preyed upon by barred owls.

Healthy habitats are vital for supporting native wildlife and plants. Explore habitats and learn about conservation and restoration in Massachusetts.

Threats

The northern flying squirrel is closer to being an old-growth specialist than any other Massachusetts mammal. Historically, the extensive clearing of mature forests that peaked in Massachusetts around the 1860s, probably extirpated the northern flying squirrel over portions of its Massachusetts range. The more recent northward expansion of the southern flying squirrel’s range throughout nearly all the northern hardwood forests with acorn-producing oaks, resulted in more contact between the two species of flying squirrels. Southern flying squirrels often carry the intestinal nematode (Strongyloides robustus). The southern flying squirrel and this parasite have co-evolved so the southern flying squirrel is seldom harmed, but when the northern flying squirrel is exposed, the infection may be fatal (Pauli et al. 2004). The loss of mature forest habitat and exposure to a new parasite from increasing southern flying squirrels, may explain the apparent decline in numbers and range contraction of northern flying squirrels in Massachusetts over past decades. In the face of climate change, if the remaining, northern and boreal, forest habitats shift north only a short distance out of Massachusetts, northern flying squirrels may disappear with them (Iverson and Prasad 2001, Weigl 2007).

Conservation

Survey and Monitoring

Since the northern flying squirrel has not been documented in Massachusetts for decades, surveys are needed to determine whether small populations still persist. Methods such as nest box surveys, camera traps, and live trapping could provide crucial data (Wells-Gosling & Heaney 1984).

Management

Protecting northern hardwood conifer forests is critical for maintaining potential habitat. Conservation of snags and dead trees is particularly important for nesting. The spread of threadworm (Strongyloides robustus), a nematode parasite carried by southern flying squirrels, may threaten the northern species. Monitoring the impact of this parasite and potential mitigation measures should be considered (Pauli et al. 2004).

References

Iverson, L.R., and A.M. Prasad. 2001. Potential changes in tree species richness and forest community types following climate change. Ecosystems 4:186-199.

Pauli, J.N., S.A. Dubay, E.M. Anderson, and S.J. Taft. 2004. Strongyloides robustus and the northern sympatric populations of northern (Glaucomys sabrinus) and southern (G. volans) flying squirrels. Journal of Wildlife Diseases 40:579-582.

Weigl, P.D. 2007. The northern flying squirrel (Glaucomys sabrinus): A conservation challenge. Journal of Mammalogy 88:897-907.

Wells-Gosling, N. and L.R. Heaney. 1984. Glaucomys sabrinus. Mammalian Species 229:1-8.

Contact

| Date published: | March 10, 2025 |

|---|