- Scientific name: Lanthus parvulus

Species of Greatest Conservation Need (MA State Wildlife Action Plan)

Description

Male northern pygmy clubtail

The northern pygmy clubtail (Lanthus parvulus) is a small, slender insect belonging to the order Odonata, suborder Anisoptera (the dragonflies), and family Gomphidae (the clubtails). The clubtails are a large, diverse group of dragonflies named for the lateral swelling at the tip of the abdomen that produces a club-like appearance which varies greatly among species. Clubtails are further distinguished from other dragonflies by their widely separated eyes, wing venation characteristics, and behavior. The northern pygmy clubtail is a member of the genus Lanthus (pygmy clubtails) that are characterized by their overall small size, reduced club, green eyes, yellow and black thorax, and dark abdomens. The thorax is black dorsally with pale stripes and two black lateral stripes fused in the middle. The abdomen is mostly black with small lateral pale-yellow spots. Females are similar to males but stockier overall, possess thin pale-yellow dorsal marks and more extensive lateral marks on the abdomen.

Adult northern pygmy clubtails range from about 33-40 mm (1.3-1.6 in) in length. Fully developed nymphs range from 19-21mm (~ 0.75 in). This species is one of the smallest clubtails in Massachusetts.

The northern pygmy clubtail shares the Lanthus genus with one other species in North America and overlaps in general distribution, the southern pygmy clubtail (L. vernalis). The species are similar in appearance as adults but can be distinguished by two lateral thoracic stripes in northern pygmy versus one stripe in southern pygmy. The species also resembles eastern least clubtail (Stylogomphus albistylus) but lack pale abdominal rings. The nymphs and exuviae can be identified using keys by Tennessen (2019).

Life cycle and behavior

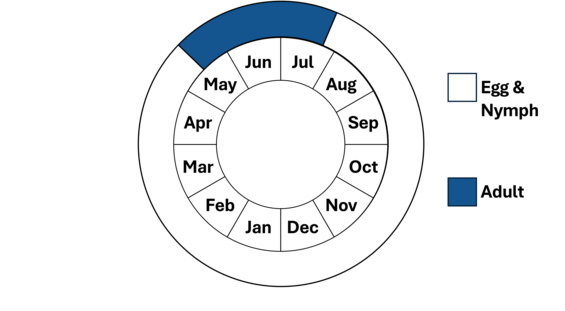

Note, nymphs are present year-round.

Northern pygmy clubtails are elusive and little is known about their life history. The egg and nymph life stages are fully aquatic. The nymphs are predators, feeding on a wide variety of aquatic insects. Nymphs spend much of their time burrowing in the bottom sediment in depositional habitats that provide them protection from predators and camouflage to catch prey. Nymphs undergo several molts (instars) for at least 2 years until they are ready to emerge as winged adults. When ready to emerge, typically in late May, the nymphs crawl out onto exposed rocks, emergent vegetation, partially submerged logs, or the steeper sections of riverbanks, where they undergo transformation to adults (a process known as eclosion). The cast nymphal exoskeletons, known as exuviae, are identifiable to species and can be a reliable, useful means to determine the presence of a species.

As soon as the freshly emerged adults are dry and the wings have hardened sufficiently, they fly off to seek refuge in the vegetation of adjacent uplands. Here, they spend several days or more feeding and maturing, before returning to their breeding habitats. During this time of wandering and maturation, clubtails are found in forest clearings, sometimes far away from the breeding site, perched horizontally on sunlit vegetation. When the maturation process is complete, the adults return to the stream to breed. In Massachusetts, the northern pygmy clubtail probably breeds from early June through late July. Upon returning to the stream, males can be found perching on rocks in the middle of the streams. From these exposed perches they make swift patrols out over the water, often returning to the same or a nearby rock. During these patrols, the males are primarily searching for mates and driving off any potential competitors. Females spend little time around the breeding habitat, often in trees, except during the brief time when they are ready to mate and lay eggs. When mating is completed, the female returns to the water to deposit her eggs in the water.

Northern pygmy clubtails have a rather short flight season with emergence beginning in late May and early June and the adults flying into July.

Distribution and abundance

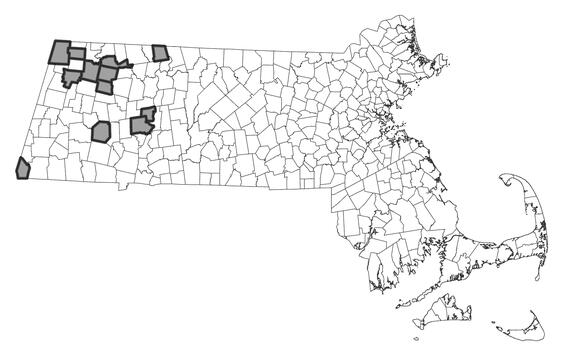

The northern pygmy clubtail has a northeastern range from Nova Scotia to Quebec south to Virginia and Tennessee. In New England the species is found in Maine, Vermont, New Hampshire, and Massachusetts. In Massachusetts, the species occurs at relatively higher elevations and occupies the Hoosic, Housatonic, Deerfield, Westfield, and Middle Connecticut watersheds. Occurrences for this species are very few including both adult and exuviae observations ((e.g., <15) and may reflect limited survey effort in its suitable habitat (e.g., forested, moderate-high gradient streams), low detection rates, potentially small population sizes, or lack of suitable habitat. The species status remains uncertain in Massachusetts.

Distribution in Massachusetts.

1999-2024

Based on records in iNaturalist and Natural Heritage databases.

Habitat

Northern pygmy clubtail inhabits small to medium sized streams of low to high gradient, cool to cold water, and often with forested riparian areas. Substrates are a mix of sand to boulder, and nymphs tend to inhabit sandy or finer deposits with organic matter in pools or along stream edges. The adults inhabit riparian areas and forested uplands, and when mature, near riffles.

Healthy habitats are vital for supporting native wildlife and plants. Explore habitats and learn about conservation and restoration in Massachusetts.

Small, cold-water, and rocky stream suitable for northern pygmy clubtail.

Threats

Degradation of water quality, alteration of streamflows, and upland habitat loss are primary threats to northern pygmy clubtail. Potential threats to water quality include pollution and sewage overflow, salt and other road contaminant run-off, and siltation from construction or erosion. The disruption of natural flow regimes by flow regulation projects, damming, and stream channelization may have a negative impact on populations. Warming stream temperatures from climate change is projected to severely reduce suitable habitat and may be the most vulnerable to climate change (Collins and McIntyre 2017). Additional threats illegal or accidental industrial discharge and hardening of channel banks and siltation that creates unstable stream habitat.

Conservation

Survey and monitoring

Standardized and targeted surveys for northern pygmy clubtail is needed to determine its status in Massachusetts. Surveys should target historical and new stream sites to determine species occupancy and population status, particularly in western Massachusetts. Surveys for exuvia and adults are likely to be more effective for detection compared to either alone. Exuviae surveys should target the species emergence period in late May to maximize detection. Adult surveys should target stream and streambank habitats during their flight period during standardized weather and time windows to maximize species detection. Multiple site visits (e.g., ≥3) may be required to detect this species. Routine monitoring of prioritized sites is needed estimate occupancy trends overtime.

Management

Upland and stream habitat protection is critical for the conservation of northern pygmy clubtail. Protection of forested upland borders of these river systems are critical in maintaining suitable water quality and are critical for feeding, resting, and maturation. Development of these areas should be discouraged, and the preservation of remaining undeveloped uplands should be a priority. Alternatives to commonly applied road salts should tested to minimize freshwater salinization. Hardened and channelized stream segments should be restored to promote natural sediment dynamics.

Research needs

Through standardized surveys, effort is needed to define habitat requirements, distribution, relative abundance, and potential breeding sites. Research effort is needed to estimate detection and occupancy rates and how other environmental variables (e.g., sample timing, weather) affect these rates. Other research efforts include projections of species distribution under climate change scenarios and climate vulnerability analysis in Massachusetts, since this species occupies cool and cold-water streams.

References

Collins S.D., and N.E. McIntyre. “Extreme loss of diversity of riverine dragonflies in the northeastern U.S. is predicted in the face of climate change.” Bulletin of American Odonatology 12,1 (2017):7-19.

Dunkle, Sidney W. Dragonflies Through Binoculars. Oxford University Press, 2000.

Lam, E. Dragonflies of North America. Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press, 2024.

Needham, J.G., M.J. Westfall, Jr., and M.L. May. Dragonflies of North America. Scientific Publishers, 2000.

Nikula, B., J.L. Ryan, and M.R. Burne. A Field Guide to the Dragonflies and Damselflies of Massachusetts. 2nd ed. Massachusetts Natural Heritage and Endangered Species Program, 2007.

Paulson, D. Dragonflies and Damselflies of the East. Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press, 2011.

Soltesz, K. Identification Keys to Northeastern Anisoptera Larvae. Center for Conservation and Biodiversity, University of Connecticut, 1996.

Tennessen, K. Dragonfly Nymphs of North America: An identification guide. Springer, 2019.

Contact

| Date published: | April 8, 2025 |

|---|