- Scientific name: Arenaria interpres

Species of Greatest Conservation Need (MA State Wildlife Action Plan)

Description

Ruddy turnstone (Arenaria interpres)

A squat, medium-sized member of the plover family, the ruddy turnstone is 21–26 cm (8-10 in) long, with a wingspan of 50–57 cm (19.7-22.4 in) and a mass of 84-190 g (3-6.7oz). The breeding plumage is a harlequin pattern of russet on the back and a unique black and white pattern on the face and breast. They have short orange legs and a short black bill. Young birds and winter adults are duller but retain enough of the basic pattern to be recognized.

Life cycle and behavior

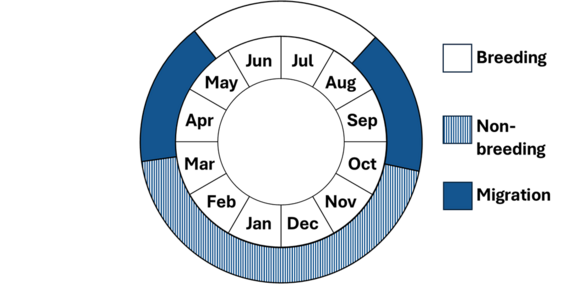

Phenology in Massachusetts. This is a simplification of the annual life cycle. Timing exhibited by individuals in a population varies, so adjacent life stages generally overlap each other at their starts and ends.

Ruddy turnstones are migratory shorebirds. They primarily breed in the high and low Arctic, with a small population extending along coastlines in Northern Europe. Individuals arrive on their breeding grounds in late May and early June. Pairs are monogamous and lay one four-egg clutch per season. Incubation is 21–24 days with both adults sharing incubation duties. Chicks are precocial and mobile within a few hours of hatching. The young self-feed, but both adults stay with chicks, guarding and leading them to high density food sources. Females depart prior to fledging, while males remain to finish parental care. Chicks are capable of first flight at 19–21 days and are fully independent of adults shortly afterwards. Migration to non-breeding habitat is quick, starting in August and throughout most of September. Sexual maturity and age at first breeding are typically 2 years. Annual survivorship is high (>65%) and varies between migratory populations. Average longevity is unknown, but the oldest individual on record was 19 years old.

Turnstones are named for their foraging behavior of using their slightly upturned bills to turn over rocks, pebbles, and other items while foraging.

Population status

The global population of ruddy turnstones is unknown but estimated at 750,000 – 1,750,000 mature individuals. While specific population trends are variable and unknown, evidence suggests a global level decline over the previous 18 years. The North American population is considered stable, but there is insufficient data on population status.

Distribution and abundance

Ruddy turnstones are distributed globally. The eastern and central North American breeding populations winter along the coasts of western Europe and coastal North and South America, respectively. The western North American and eastern Siberian population migrates to southeastern Asia, Australia and the west Pacific. The eastern and central Russian population winters in the eastern Mediterranean, the Red Sea, Persian Gulf, and Indian Ocean. The European population winters in Morocco and western Africa. Patterns of abundance are unknown.

In Massachusetts, the ruddy turnstone is a locally abundant migrant and is locally uncommon in winter along coastal shorelines. Migration concentration areas in Massachusetts include the Monomoy Islands and South Beach in Chatham, and the mouth of the North River in Scituate.

A ruddy turnstone flips over a clam on the shoreline, using its beak like a tool to forage for food on the sand.

Habitat

Breeding habitat consists of rocky coasts and tundra. Ruddy turnstones breed in a variety of habitats, including marshy slopes, well-drained clay tundra flats, and sparsely vegetated habitats along coasts. Even with the documented range in habitat types, food availability exerts a strong influence on breeding areas. Ruddy turnstones typically breed near wet areas, such as marshes, streams or beaches, and breeding season diets and movements are often dictated by the emergence of dipteran insects. Diets during the breeding season are supplemented by spiders, beetles, Lepidoptera larvae, Hymenoptera, and some fruits and berries.

Non-breeding habitat is coastal, although some populations will frequent inland, freshwater lake beaches and shorelines during migration. Ruddy turnstones may form critical staging sites at habitats with phenological food sources (e.g. horseshoe crab egg-laying in mid-Atlantic states). Non-breeding diets are incredibly diverse, and they are efficient, opportunistic feeders and scavengers. In Massachusetts, migrant and wintering ruddy turnstones inhabit sand, gravel, or cobble coastal beaches, intertidal areas, and islands. They consume gull and tern eggs throughout their non-breeding range and regularly exert predation pressure on Massachusetts common (Sterna hirundo) and roseate tern (Sterna dougallii) colonies in the early and mid-egg laying period.

Healthy habitats are vital for supporting native wildlife and plants. Explore habitats and learn about conservation and restoration in Massachusetts.

Threats

Ruddy turnstones are not globally threatened but are listed as near threatened by the International Union for Conservation of Nature. Anthropogenic habitat loss or degradation of winter grounds and along migratory routes are a significant concern for this species. Economic development, pollution, and hunting threated ruddy turnstones on a global scale, but the extent of impacts is unknown. As with many migratory shorebirds, the loss of important migratory stopover habitats and food resources would be detrimental to the population.

Disturbance caused by human recreational activities (pedestrians, off-road vehicles, dogs) and oil spills are threats to ruddy turnstones in Massachusetts.

Conservation

MassWildlife’s Natural Heritage Endangered Species Program (NHESP) does not track occurrences of ruddy turnstones in Massachusetts. Ruddy turnstones are included in the National Audubon Society’s Christmas Bird Count. These surveys have indicated a positive trends of winter populations in Massachusetts.

Hunting and the millinery trade, particularly in New England, significantly decreased the migratory population of ruddy turnstones in the late 19th century. Ruddy turnstones in Massachusetts have likely benefitted from protections awarded by the Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918.

Effective management for this species would include habitat conservation measures throughout its range. Additionally, further monitoring is needed for ruddy turnstones in many aspects of their biology and ecology. This species would benefit from annual productivity monitoring, survival studies, threat assessments, as well as migratory tracking and research identifying critical migratory food resources and habitats.

References

BirdLife International (2024). Species factsheet: Ruddy Turnstone Arenaria interpres. https://datazone.birdlife.org/species/factsheet/ruddy-turnstone-arenaria-interpres

Mass Audubon. State of the Birds: Ruddy Turnstone Arenaria interpres. N.d. https://www.massaudubon.org/our-work/birds-wildlife/bird-conservation-research/state-of-the-birds/find-bird-groups?id=RUTU

Nettleship, D. N. (2020). Ruddy Turnstone (Arenaria interpres), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (S. M. Billerman, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi-org.silk.library.umass.edu/10.2173/bow.rudtur.01

Veit, R., and W.R. Petersen. 1993. Birds of Massachusetts. Massachusetts Audubon Society, Lincoln, Massachusetts.

Contact

| Date published: | April 3, 2025 |

|---|