- Scientific name: Calidris alba

Species of Greatest Conservation Need (MA State Wildlife Action Plan)

Description

Sanderling (Calidris alba)

The sanderling is a relatively small, active sandpiper of the outer beaches. Adult sanderlings are about 18-20 cm (7-7.9 in) in length and weigh 40-100 g (1.4-3.5 oz). Birds in spring are bright rusty about the head, back, and breast. Fall and winter birds are very pale, with pale gray back, white underparts, and black shoulder. Sanderlings have bold white wing stripes in both plumages. Sexes are alike except males average brighter than females in breeding plumage, but individual variation and feather wear often obscure these differences as the breeding season progresses.

Life cycle and behavior

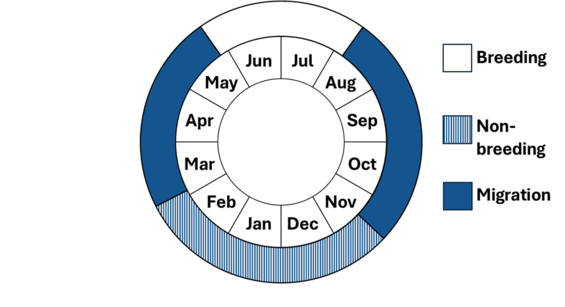

Phenology in Massachusetts. This is a simplification of the annual life cycle. Timing exhibited by individuals in a population varies, so adjacent life stages generally overlap each other at their starts and ends.

Sanderlings are migratory shorebirds. They breed on Arctic tundra and primarily overwinter on sandy beaches on the Pacific and Atlantic coasts. Both sexes arrive on their breeding grounds in late May and early June. Clutch size is usually four eggs and incubation lasts 23-27 days, with both adults sharing incubation duties. Chicks are precocial and downy. Within two days after hatching, attending parent leads offspring to marshy swales associated with ponds or lakes, where they feed on surface-dwelling insects. Parents are known to remain with offspring up to and at least the age of near-sustained flight (15 days). At 17-21 days, most tending adults leave their offspring, and juveniles gather in small flocks (4-15 individuals). Yearling sanderlings molt and migrate to breeding grounds later than adults and likely most do not breed until the second year, although quantitative data are lacking. The longest life span reported is at least 13 years.

During the breeding season, sanderlings feed on insects, spiders, and crustaceans. When animal prey is not available, they will take plant material (buds, shoots and roots of certain species, grass seeds, algae, and mosses). During migration and in winter they feed on a wide range of prey, depending on the area. This includes hippid crabs, isopods, polychaete worms, small bivalve mollusks, horseshoe-crab eggs, and small crustaceans. Sanderlings feed by picking and probing. While running, they will skim food from shallow pools by dipping their bill to the surface.

Sanderlings are gregarious. They arrive on the breeding grounds in mixed-sex flocks of 10-20, occasionally singly or in pairs. In winter and on migration, they associate with almost any other small shorebird and typically forage in intraspecific flocks. When foraging on sandy beaches, sanderlings move quickly, running ahead of incoming waves and chasing after receding ones, probing the sand for food.

Population status

Global population size is unknown. Based on broad-scale surveys, the North American population is estimated to be 300,000 individuals, with roughly 140,000 on breeding grounds in the Canadian Arctic. In winter, the highest densities are on the Pacific coast of North America and South America. Sanderlings are common migrants and common wintering birds in Massachusetts. The Monomoy Islands and South Beach in Chatham support the largest numbers of migrating sanderlings, although peak numbers have declined since the 1950s.

A sanderling forages along the shoreline, its pale plumage blending with the sandy beach.

Distribution and abundance

Sanderlings are migratory shorebirds. Their breeding range is circumpolar, with the highest numbers in the Canadian Arctic archipelago, Greenland, and high-arctic Siberia. During the non-breeding season, they are a cosmopolitan bird and can be found throughout almost all temperate and tropical marine sandy beaches.

Habitat

On the breeding grounds, sanderlings nest in tundra habitat in relatively close proximity to wet areas for young to forage. In Massachusetts, sanderlings inhabit sandy coastal beaches, sandspits, and intertidal flats. To a lesser extent, the species occupies sand- and mudflats, lagoons, and intertidal rocky shores.

Healthy habitats are vital for supporting native wildlife and plants. Explore habitats and learn about conservation and restoration in Massachusetts.

Threats

Regional populations are in rapid decline, with the apparent cause being habitat degradation and increasing recreational use of sandy beaches. Disturbance associated with human recreation on beaches, including off-road vehicle use and dog-walking, loss or degradation of sandy beach habitat caused by human development or construction of hard structures, such as seawalls, jetties, armored coastal banks, and oil spills are all threats to sanderlings in Massachusetts. Continent-wide data suggest significant declines on the Atlantic coast of U.S. could be due to chronic disturbance by human activity at migration staging areas.

Apparent reduction in horseshoe crab populations along the U.S. mid-Atlantic coast, where the species is harvested for use as bait, could impact migrating sanderlings, which feed on the horseshoe-crab eggs. Ongoing research, however, shows sanderlings are less affected than other shorebirds, in part due to their more diverse diet and the greater mass buffer when they arrive.

Climate change is a threat as predicted increases in temperature in the high Arctic might eliminate almost all sanderling nesting habitat and alter topography at such a rate that invertebrate prey populations will be adversely affected.

Plastic trash in the environment poses a threat as it can be mistaken as food by seabirds and shorebirds and ingested or cause entanglement. Ingested plastics, common for seabirds, can block digestive tracts, cause internal injuries, disrupt the endocrine system, and lead to death. Entanglement from fishing gear and other string-like plastics can cause mortality by strangulation and impairing movements.

Conservation

Various regulations and conservations efforts have been put into place. Regionally, in 1985 the lower estuary of Delaware Bay declared a reserve for shorebird conservation and New Jersey's Division of Environmental Protection established emergency procedures to be used in the event of chemical spills during critical migratory periods. Since 1992 the Western Hemisphere Shorebird Reserve Network expanded to form Wetlands for the Americas, which focuses on protecting against loss of key habitat and chronic disturbance at sites traditionally used by sanderlings. In New Jersey, harvesting of horseshoe crabs has been prohibited along certain Delaware Bay beaches, shoreline, and adjacent waters year-round, and elsewhere it has been limited and requires a permit. MassWildlife’s Natural Heritage and Endangered Species Program (NHESP) does not track occurrences of sanderlings in Massachusetts.

Research on sanderlings has been focused largely during the nonbreeding season. Therefore, the sanderling mating system, population dynamics, and other aspects of the reproductive season are significantly understudied.

Avoid or recycle single-use plastics and promote and participate in beach cleanup efforts.

References

Macwhirter, R. B., P. Austin-Smith Jr., and D. E. Kroodsma (2020). Sanderling (Calidris alba), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (S. M. Billerman, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi-org.silk.library.umass.edu/10.2173/bow.sander.01

Veit, R., and W.R. Petersen. 1993. Birds of Massachusetts. Massachusetts Audubon Society, Lincoln, Massachusetts.

Contact

| Date published: | April 3, 2025 |

|---|