- Scientific name: Egretta thula

- Species of Greatest Conservation Need (MA State Wildlife Action Plan)

Description

Snowy egret (Egretta thula)

A medium-sized white heron, the snowy egret is 50-68.5 cm (20-27 in) in length, weigh about 370 g (13 oz), and have a 100 cm (39.4 in) wingspan. They have a slender black bill, black legs, yellow feet, thin neck, and a yellow patch in front of their eyes. Adult snowy egrets have long, white plumes on the neck, back, and breast during breeding season. Their voice is a low croak. Although this species is generally distinctive, it can be confused with juvenile little blue herons and the larger great egret.

Life cycle and behavior

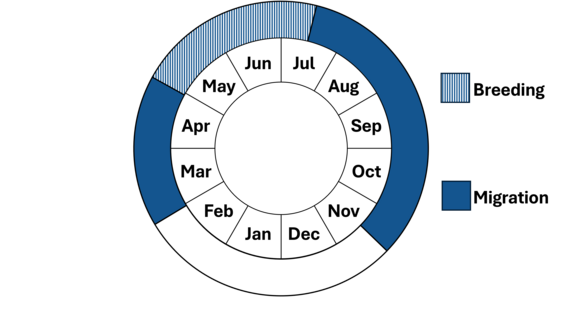

Figure 1. Phenology in Massachusetts. This is a simplification of the annual life cycle. Timing exhibited by individuals in a population varies, so adjacent life stages generally overlap each other at their starts and ends.

Snowy egrets use their long, yellow feet and sharp beak to forage in the mud for fish, amphibians, crustaceans, worms, and insects. When searching for food, they can be observed swaying their head, vibrating their bill, and flicking their wings. Snowy egrets are social birds, often seen foraging and nesting in colonies with a mix of species including herons, ibises, and other egrets.

During breeding season, males will perform elaborate, vocal courtship displays to attract a female. Males select a nesting site and start to build the nest prior to securing a mate. Once the snowy egrets pair up, they will finish building the nest and continue to defend the area from predators like raccoons, birds of prey, and reptiles. The female will lay 2-6 eggs and both adults will incubate them for 24-25 days.

Population status

Using data from the North American Breeding Bird Survey, Partners in Flight estimates the breeding population at just over 2 million. A 1994-95 comprehensive census in Massachusetts reported 746 nesting pairs at 9 colonies. In 2008, 456 nesting pairs were identified in the state. Though several small colonies showed some increases, and 3 new colonies were located, there were large losses at 3 sites in Salem, Boston Harbor, and Hingham. The species has continued to decline with 325 nesting pairs documented in 2013 and 308 pairs in 2018.

Distribution and abundance

Prior to the 1900s, snowy egret populations suffered significant losses due to the killing of birds for their breeding plumes for women’s hats. In the early 1910s, plume hunting was restricted, and populations have since rebounded. The snowy egret was considered a rare vagrant from the south until the late 1940s. Its breeding range has expanded northward into Massachusetts during the last 50 years. Snowy egrets nest colonially on coastal islands, and the first reported nesting in Massachusetts was in 1955 in Dennis.

Habitat

Snowy egrets nest in mixed colonies with other species of egrets and herons. The nests are in trees or patches of shrubs on coastal islands, presumably to reduce the likelihood of mammalian predation. Snowy egrets forage in marshes and ponds near their breeding colonies for small fish, snails, and aquatic invertebrates.

Healthy habitats are vital for supporting native wildlife and plants. Explore habitats and learn about conservation and restoration in Massachusetts.

Snowy egrets nesting

Threats

The nation-wide loss of wetlands is an ongoing threat to snowy egret populations. Predation and human disturbance at nesting colonies are threats to snowy egrets in Massachusetts. Loss of nesting trees due to storm damage, physical deterioration caused by years of exposure to bird excrement, or human cutting and clearing may also be threats; these will certainly cause breeding populations to relocate. Oil spills and ingestion of plastics and contaminants can be a threat to this species.

Conservation

Protection and management of nesting colonies is important for the conservation of snowy egrets. At some sites, habitat restoration efforts could improve conditions for colony persistence or establishment, especially at sites that formerly hosted colonies but where the habitat is no longer suitable. Identifying and protecting important wintering ground habitat would support the full annual cycle conservation of the species.

References

Sauer, J.R., J.E. Hines, and J. Fallon. 2019. The North American Breeding Bird Survey, Results and Analysis 1966 - 2019. Version 2019.1. USGS Patuxent Wildlife Research Center, Laurel, Maryland.

Parsons, K. C. and T. L. Master (2020). Snowy Egret (Egretta thula), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (A. F. Poole and F. B. Gill, Editors). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.snoegr.01

Veit, R., and W.R. Petersen. 1993. Birds of Massachusetts. Massachusetts Audubon Society, Lincoln, Massachusetts.

Contact

| Date published: | April 24, 2025 |

|---|