- Scientific name: Clemmys guttata

- Species of Greatest Conservation Need (MA State Wildlife Action Plan)

Description

The spotted turtle is placed within the third-largest turtle family, Emydidae. It is one of North America’s smallest turtle species, averaging 8.0–12.5 cm (3–5 in) in carapace length. This cryptic species is named for the bright yellow circular spots that dot its smooth, keelless black carapace (upper shell). The number of spots varies significantly among individuals, and these unique patterns can help identify individual turtles.

Hatchlings generally have one spot per scute (keratinous scales that cover the shell), although some may lack spots altogether. In adult turtles, the spots may be sparse or absent entirely, and individuals may be stained with tannins or iron oxide. The plastron (bottom shell) is creamy yellow with dark blotches along its edges. The skin is usually gray to black, with occasional yellow or orange spots on the head, neck, and limbs. The undersides of the limbs and other soft parts can appear in shades of pink, orange, or salmon-red.

Adult spotted turtles are sexually dimorphic and dichromatic, meaning there are distinct physical characteristics between sexes. Males typically have a relatively long, thick tail and a concave plastron. Males often have flatter carapaces, brown irises, and a gray chin. In contrast, females tend to have a more domed carapace, a flat or convex plastron, yellow-orange irises, a pinkish-orange chin, and a thin, shorter tail. Across their geographic distribution, females tend to be larger in body size than males.

Hatchlings emerge from their eggs around 2.8 cm (1.1 in) in length, and their carapace is blue-black or black-grey, as noted above, with a yellow spot on each scute. Some hatchlings may lack spots on some scutes or entirely. Their yellow to light-orange plastron typically has a central black blotch, and their head is spotted, sometimes extending to the neck

Similar species

Spotted turtles could be mistaken for young Blanding’s turtles (Emydoidea blandingii) due to their similar dark carapaces and yellow markings. Indeed, some Blanding’s turtles are prominently spotted. However, Blanding's turtles typically have reticulated, pale yellow, wormy lines that radiate out from the center, compared to the distinct round yellow spots characteristic of spotted turtles.

Additionally, Blanding’s turtles are significantly more massive, with a carapace length ranging from 17.5-23 cm (7–9 in). Darker spotted turtles with fewer spots could resemble bog turtles (Glyptemys muhlenbergii). However, bog turtles are much rarer and can be distinguished by the distinctive yellow or orange splotch near their tympanum and on the side of their neck. Road-killed specimens of spotted turtle could easily be confused with Eastern box turtle (Terrapene carolina), wood turtle (Glyptemys insculpta), Blanding’s turtle, or bog turtle.

Life cycle and behavior

Female spotted turtle nesting in loamy substrate.

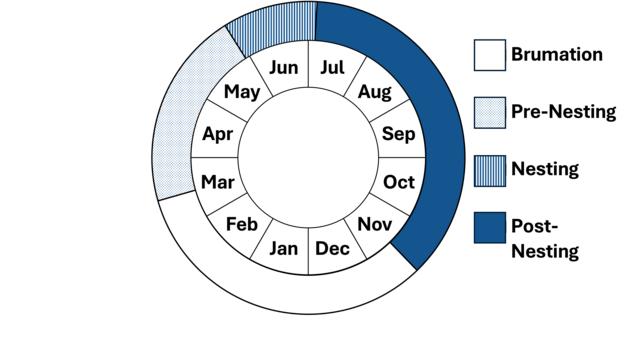

Spotted turtles are a relatively diurnal species, being active during the daylight hours and seeking shelter in a hibernacula mid-day to evening. However, during the nesting season, females remain active after dusk. Early spring (around May–March) is the peak activity season for spotted turtles, where both males and females will emerge from their overwintering hibernacula and spend much time basking. This is done singly or in groups and occurs on partially submerged logs, rocks, tussocks of sedge, or on the shoreline. Generally, spotted turtles bask more on cold, sunny days than warm, cloudy ones when they feed more often. During the late summer, they are not easily found; to avoid desiccation and high temperatures, they will enter a short period of dormancy, also known as aestivation. spotted turtles aestivate in cooler and more humid areas, such as the mud bottom of waterways like vernal pools, inundated deer trails, muskrat burrows or lodges, or within moist sphagnum mounds.

Spotted turtles mature at about 8–10 years of age. Courtship and mating occur from March–May before nesting season and generally occur in water. The timing of this process varies geographically but generally occurs after they emerge from overwintering and reoccur in the fall. In their more northern distributions, researchers have documented them copulating under ice during the winter months. Courtship of the females involves a long (up to one hour) and frantic chase by the male. Several males pursue a single female simultaneously, biting each other and sometimes the female in the process.

In Massachusetts, female spotted turtles primarily nest in June, usually during the late afternoon or evening, as mentioned previously. They select various nesting sites, including the inside of hummocks in moist sphagnum mounds, grassy tussocks, or well-drained loamy soil near transmission line towers or on rail edges above adjacent wetlands. The female digs a 5 cm (2 in) deep hole, taking up to one hour or more to finish depositing her eggs. She positions each egg in the nest with her hind feet during the egg-laying process. When finished laying, she scoops the excavated earth back onto the eggs and smooths over the covered nest by dragging her plastron over the site to minimize nest predation. spotted turtle clutch size also varies geographically, with populations at higher latitudes typically laying more eggs per clutch (~4–7), while southern populations tend to have fewer eggs per clutch (~3–4). Female spotted turtles lay eggs characterized by their smooth, white, elliptical shape and have temperature sex-dependent determination (TSD). Typically, the eggs incubate for 10–12 weeks. Hatchlings emerge from the nest in August or September for food and shelter on the edges of grassy, wet meadow areas and bogs. They may over-winter in the nest. Hatchlings are particularly carnivorous, hunting small land and water insects, worms, and snails. As they sexually mature, spotted turtles transition to an omnivorous diet, selecting various resources ranging from aquatic vegetation to larval amphibians, slugs, snails, insects, and worms.

In post-nesting season, spotted turtle activity dwindles as they return to their overwintering sites. They aestivate during warmer summer temperatures (>32°C) to avoid desiccation and predation. In the late season, their movements are confined to wetlands until they enter their hibernacula, where they overwinter communally.

Spotted turtles select overwintering sites deep in the muck, or in submerged tree roots, where they remain insulated from freezing temperatures. During winter months, they enter a state called brumation, slowing their physiological processes and lowering their metabolic rates to survive the cold. If temperatures rise during winter, they may briefly emerge to feed, rehydrate, or even copulate under the ice. They then return to their hibernacula when temperatures drop again and re-emerge in the spring.

Population status

The spotted turtle occurs in small, localized populations that typically number fewer than 100 individuals in Massachusetts. Geographically, this species’ population is declining primarily due to adult mortality and lack of successful reproduction. Although this species is relatively well-studied, long-term research on population sizes remains limited, with most studies focusing on single generations. However, studies that have monitored population sizes over time, including in Massachusetts, have reported a nearly 50% decline over a 25–30 year period.

In 2006, the spotted turtle was delisted from Massachusetts’s special concern, threatened, or endangered species status. However, this does not imply an abundance of the species; instead, it reflects that populations are generally found in isolated occurrences. At the turn of the century, spotted turtles were considered one of the most common turtle species in Massachusetts, if not the most common. They have been documented in over 200 towns across the state, with more than 800 occurrences reported to the MassWildlife’s Natural Heritage and Endangered Species Program (NHESP). Despite this widespread presence, many of these populations contain fewer than 12 individuals, which is insufficient to maintain sustainable populations for the species’ future.

Distribution and abundance

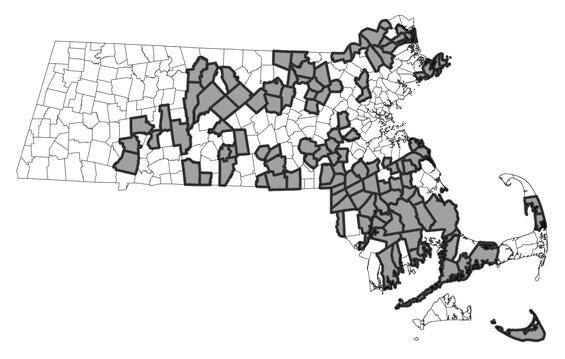

Spotted turtles have a broad geographic distribution, from southern Ontario, southward along the northeastern seaboard from Maine to northern Florida. Their range extends westward through Ontario, New York, and several midwestern states, including southern and western Michigan, northeastern Illinois, northern Indiana, and central Ohio. In Massachusetts, they are found throughout the state in all 14 counties, with smaller and more restricted populations in the Housatonic and Connecticut River Valleys.

Distribution in Massachusetts.

2000-2025

Based on records in the Natural Heritage Database.

Habitat

Spotted turtles exhibit seasonal patterns in their habitat selection, inhabiting a variety of wetland environments throughout Massachusetts. Spotted turtles are found primarily in Palustrine Wetlands, including forested, scrub-shrub, emergent, and non-forested wetlands. Their movement between wetlands is most pronounced during the spring and early summer when they are commonly found in marshy meadows, bogs, fens, small ponds, brooks, ditches, and other shallow, seasonal (ephemeral) pools and emergent marshlands. As summer progresses, their movements become less frequent, and they often aestivate in upland forests or open upland habitats.

This species requires soft substrates and prefers areas with aquatic vegetation. They often bask cryptically along the water's edge, in brush piles, overhanging vegetation, sphagnum mats, or hide in muck and detritus to avoid predation or desiccation.

Healthy habitats are vital for supporting native wildlife and plants. Explore habitats and learn about conservation and restoration in Massachusetts.

Threats

The spotted turtle faces numerous threats that have significantly impacted their populations. This species is particularly vulnerable due to its life history traits and the following challenges listed in the “Status Assessment and Conservation Plan for the spotted turtle in the Eastern United States” (Willey et al. 2022):

- Habitat fragmentation and loss: Human activities such as land development and road construction fragment their habitats, limiting access to critical resources and increasing isolation between populations. Within the Northeast, development has stripped away 16.2% of known spotted turtle sites.

- Illegal collection: Humans have commercially marketed spotted turtles for the pet trade for the last 50 years. In recent years, authorities and researchers have identified illegal collection and poaching as significant concerns, with spotted turtles being among the most frequently confiscated species in the United States. This illegal activity is occurring at a global scale that is threatening the long-term viability of their populations.

- Elevated Adult Mortality: Spotted turtles do not reproduce until they are approximately 7–15 years old in the wild, resulting in slow population growth rates, population recovery, and adaptation.

- Mesopredation: With a high mortality rate among hatchlings, juveniles, and nests due to subsidized depredation from mesopredators (e.g. raccoons, skunks, opossums), populations struggle to rebound from elevated mortality.

- Road Mortality: These turtles travel widely across landscapes, often crossing roads while searching for nesting or foraging sites, which increases their risk of being killed by motor vehicles. Roads also contribute to habitat fragmentation, making it difficult for turtles to find mates or suitable habitats.

- Invasive Species: Invasive species disrupt native ecosystems, creating competition for food, space, and even encroaching nesting habitat. Invasive plants can alter and destroy wetlands, which these species depend on.

- Beaver Activity: Beaver activity can push spotted turtles into marginal habitats by damming up rivers and flooding their native habitats, completely altering the hydrology and geology of the surrounding landscapes.

Climate change exacerbates these risks (Willey et al. 2022; Staudinger et al. 2024):

- Temperature shifts impact nesting success, as spotted turtles are highly sensitive to temperature fluctuations that affect egg development.

- Change in sex ratio: Studies report a lower proportion of males in the warmer parts of their range, indicating that these extreme shifts in temperature cannot only affect egg development but also lead to climate-induced, temperature-dependent sex ratio shifts.

- Changes in precipitation patterns can alter wetland water table levels, negatively altering the hydrology of turtle habitats, particularly for overwintering and foraging.

- Sea level rise: The Commonwealth of Massachusetts has a few unique spotted turtle populations located along coastal areas and islands. Consequently, rising sea levels pose a threat due to the accelerating global increase in mean sea levels. With higher sea levels and intense storm surges, concerns such as coastal overwash and flooding, as well as the conversion of freshwater ecosystems into saltwater systems, make these environments intolerable and unsuitable for this species. Additionally, floods can destroy nests and damage critical habitats, further threatening populations.

A comprehensive approach involving habitat protection, road mitigation, and public education is essential for addressing these challenges.

Conservation Action Plan

Conservation Planning

As mentioned, the state of Massachusetts delisted the spotted turtle from its state's endangered species list in 2006, but this does not mean that the decline of the species is no longer a cause for concern, nor should it be ignored in conservation planning and management.

In 2019, the Spotted, Blanding’s, and Wood Turtle Conservation Symposium was held in West Virginia, where 48 experts presented on conservation monitoring and management techniques, genetics, and methods to combat illegal collection, with a specific focus on spotted turtles. Surveys of these experts identified significant threats to the spotted turtle, which varied by region. In the Northeast, experts identified the top three threats out of six listed categories: Habitat Loss/Fragmentation, Illegal Collection, and Elevated Adult Mortality (see Willey et al. 2022). In response to these threats, they ranked the necessary conservation actions, with Land Protection, Addressing Illegal Collection, and Reducing Road Mortality as the top three, out of seven categories listed (see Willey et al. 2022).

The Eastern Spotted Turtle Working Group (ESTWG) developed a multifaceted conservation plan, known as the ‘Status Assessment and Conservation Plan for the spotted turtle in the Eastern United States’ in 2016 to address these pressing issues within the Eastern United States (Maine to Florida). This conservation plan includes regional monitoring, habitat management, and the protection of key sites.

Based on the regional fundamental goal of maintaining and conserving self-sustaining populations throughout the extent of the current occupied range, which emphasizes 'Focal Core Areas'—areas that are representative of the ecological, genetic, and political context in which the species currently lives—the ESTWG formed a Conservation Action Plan (CAP) that focuses on five objectives:

Objective 1: Minimize net degradation/loss of site quality within “Focal Core Areas” identified in the Conservation Area Network (CAN)

Objective 2: Reduce major threats besides habitat loss

Objective 3: Maintain adaptive capacity of known spotted turtle populations

Objective 4: Address data gaps

Objective 5: Continue collaboration and coordination

From this status assessment and CAP, state of Massachusetts must implement these objectives with proper inventory and monitoring protocols to address research needs and management actions which are further elaborated below.

Inventory and Monitoring

There are many factors within spotted turtle habitat’s that influence their population abundance, viability, and age structure. Gathering inventory on their habitat is important to identify key focal areas for conservation management.

Effective monitoring is critical to conserving the spotted turtle (Clemmys guttata). For conservation efforts to be successful, the ESTWG created a “Regional Spotted Turtle Assessment Protocol” to outline a standardized and flexible methodology for sampling spotted turtles in the eastern part of their range (see Willey et al. 2022). This protocol involves two levels of trap-based assessments, Rapid and Demographic. This protocol is applied regionally utilizing mark-recapture studies to assess the current demographics and size of extant populations.

Radiotelemetry is another form of survey and monitoring of animals to gather information on home range size, movement, and habitat selection. Researchers monitor spotted turtles using telemetry techniques range wide, providing information on population isolation, insight on habitat corridors and connectivity, nest site selection, home range size and movement patterns. Results from these studies can provide implications for habitat management through comprehension of species’ habitat selection. By monitoring spotted turtle populations and their habitats, we can gather the data needed to prioritize conservation efforts, secure vital habitats, and ensure the long-term survival of this iconic species.

Research Needs

Ongoing scientific research is necessary to fill knowledge gaps about spotted turtle ecology, population dynamics, and the effects of environmental changes. Key research priorities include:

- Population genetics: To assess genetic diversity, connectivity between populations, and to understand dispersal patterns.

- Habitat selection and use: Identifying the factors that influence habitat use across seasons, including changes in wetland hydrology and vegetation.

- Dispersal studies: Understanding corridors and barriers to movement, particularly in fragmented landscapes, to identify strategies for improving connectivity.

- Road ecology: Investigating how roads impact spotted turtle populations and developing effective mitigation measures to reduce road mortality.

- Climate change impacts: Studying the effects of shifting weather patterns, temperature fluctuations, and extreme weather events on nesting success, habitat availability, and overall population health.

Management Needs

MassWildlife is dedicated to the oversight of conservation and monitoring of the spotted turtle within the state of Massachusetts. Partnering with agencies such as the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (including the Eastern Massachusetts National Wildlife Refuge), Department of Conservation and Recreation (DCR), and other large landowners should continue to protect larger known populations. Effectively managing spotted turtle populations begins with prioritizing the restoration and maintenance of their habitats. Habitat management, through techniques like prescribed burning, invasive species removal, and the protection of wetlands, plays a pivotal role in ensuring the long-term survival of this species.

The use of telemetry and standardized trapping additionally provides researchers and managers valuable insights into the behavior and spatial ecology of spotted turtles, enhancing our understanding of their habitat needs. Researchers collecting data on spotted turtles can use these methods to form strategies that assist in the improvement of habitat quality and connectivity.

Active habitat management through MassWildlife and partnering organizations are required in large populations and data deficient populations. This may include:

- Improvement of overwintering and nesting habitat to reduce road mortality and predation

- Periodic re-evaluation of the spotted turtle’s conservation status in the state of Massachusetts

- Spatial monitoring of populations to understand and improve habitat and population connectivity

- Public education and outreach to promote sustainable land practices and reduce fragmentation and habitat loss

Ultimately, targeted habitat restoration and management strategies that maintain functional, connected ecosystems will not only protect the spotted turtle from immediate threats but also bolster population health and resilience in the face of environmental challenges.

References

Buchanan, S.W., B. Buffum, and N.E. Karraker. 2017. “Responses of a spotted turtle (Clemmys guttata) population to creation of early-successional habitat.” Herpetological Conservation and Biology 12, 3:688–700.

Coury, M. 2022. “Spatial ecology and habitat selection of a spotted turtle (Clemmys guttata) population in southwest Michigan.” Scholarworks: Grand Valley State University.

Ernst, C.H. 1976. “Ecology of the spotted turtle, Clemmys guttata (Reptilia, Testudines, Testudinidae), in southeastern Pennsylvania.” Journal of Herpetology 10, 1:25–33.

Ernst, C.H. and J.E. Lovich. 2009. turtles of the United States and Canada: Second Edition. John Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, MD, USA.

Garrison, J.C., L.L. Willey, and M.T. Jones. 2023. “Nesting ecology of spotted turtles (Clemmys guttata) at an anthropogenic site in Massachusetts.” Herpetological Conservation and Biology 18, 3:560–568.

Howell, H. J., and R.A. Seigel. 2019. “The effects of road mortality on small, isolated turtle populations.” Journal of Herpetology 53, 1:39–46.

Jones, M.T., and S.L. Koch. 2024. “Spotted turtles (Clemmys guttata) on a Morainal Island Affected by Coastal Erosion.” Northeastern Naturalist 31, 12:C48–C56.

Litzgus, J.D. 2006. “Sex differences in longevity in the spotted turtle (Clemmys guttata)." Copeia, 2:281–288.

Milam, J.C., and S.M. Melvin. 2001. “Density, habitat use, movements, and conservation of spotted turtles (Clemmys guttata) in Massachusetts.” Journal of Herpetology 35, 3:418–427.

Pelletier, S.K., L. Carlson, D. Nein, and R.D. Roy. 2005. “Railroad crossing structures for spotted turtles: Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority–Greenbush rail line wildlife crossing demonstration project.” UC Davis: Road Ecology Center.

Rasmussen, M.L., and J.D. Litzgus. 2010. “Habitat selection and movement patterns of spotted turtles (Clemmys guttata): effects of spatial and temporal scales of analyses”. Copeia, 1:86–96.

Staudinger, M.D., A.V. Karmalkar, K. Terwilliger, K. Burgio, A. Lubeck, H. Higgins, T. Rice, T.L. Morelli, and A. D'Amato. 2024. “A regional synthesis of climate data to inform the 2025 State Wildlife Action Plans in the Northeast US DOI Northeast Climate Adaptation Science Center Cooperator Report.”2024: 1–406.

Willey, L.L., M.K. Parren, M.T. Jones and the Eastern spotted turtle Working Group. 2022. Status Assessment and Conservation Plan for spotted turtles in the Eastern United States. Technical Report to the Virginia Dept. of Wildlife Resources and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

Contact

| Date published: | March 6, 2025 |

|---|