- Division of Marine Fisheries

Longfin squid (formerly Loligo) represent an important species for local and regional commercial and recreational fishermen, as well as marine predators and seafood enthusiasts. Year-round demand exists and shoreside processing, shipping, and marketing infrastructure have been bolstered in recent decades. A recent economic study found that an average year for the commercial longfin squid fishery created over 2,500 full-time jobs, nearly $100 million in total income and over $240 million in total economic output (Scheld 2020). The longfin squid fishery generally consists of an offshore fishery in the fall-winter months and an inshore fishery in the spring-summer months. While over half of annual longfin squid catch is landed in Rhode Island ports, Massachusetts state waters host an important inshore fishery from late April through early June each year.

Due to the importance of squid as a forage species and the fishery’s inshore presence, fishery stakeholder groups have expressed concern over the impacts of the squid trawl fishery. In response to a request from Massachusetts state legislators, a report describing the spring longfin squid fishery in Nantucket Sound and adjacent waters was commissioned in 2019. The resulting report, Characterization of the Massachusetts Spring Longfin Squid Fishery, was completed this spring and presented to the Marine Fisheries Advisory Commission in May. This report, available on the DMF website, summarizes biological information, presents historical landings, profiles the fishing fleet, details the extensive sea sampling dataset, and discusses concerns that have been raised by scientists, stakeholders and managers alike.

The fleet of bottom trawl vessels that pursues longfin squid in Massachusetts state waters is managed both by the Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries and the Mid-Atlantic Fishery Management Council at a federal level. Properly-permitted vessels may target squid with the following restrictions, no longer than 72 feet overall, towing nets with ground-gear no larger than 12” in diameter, and nets with codend meshes no smaller than 17/8” may target longfin squid in the squid trawl exemption zone from April 23-June 9 each year. The DMF Director may also extend the squid trawl season beyond June 9. The “Squid Report” found that this fishery is primarily composed of 40-65 foot trawlers landing in Massachusetts and Rhode Island ports. The Massachusetts boats were usually “day boats” while the Rhode Island-based vessels conducted trips of 3-6 days on average. Landings from Nantucket Sound in the 2013-2017 time period studied in the Squid Report averaged 1.05 million pounds each spring season, ranging from a low of 70,000 pounds in 2013 to 1.78 million pounds in 2016. Average annual price for squid sold by fishermen in MA was $1.56/lb, ranging from $0.97/lb to $2.32/lb in 2013. Landings data clearly showed that 2013 was a very poor year for squid fishing in MA state waters. In addition to longfin squid, the top four most valuable species landed during squid trips were scup, summer flounder (fluke), butterfish and black sea bass.

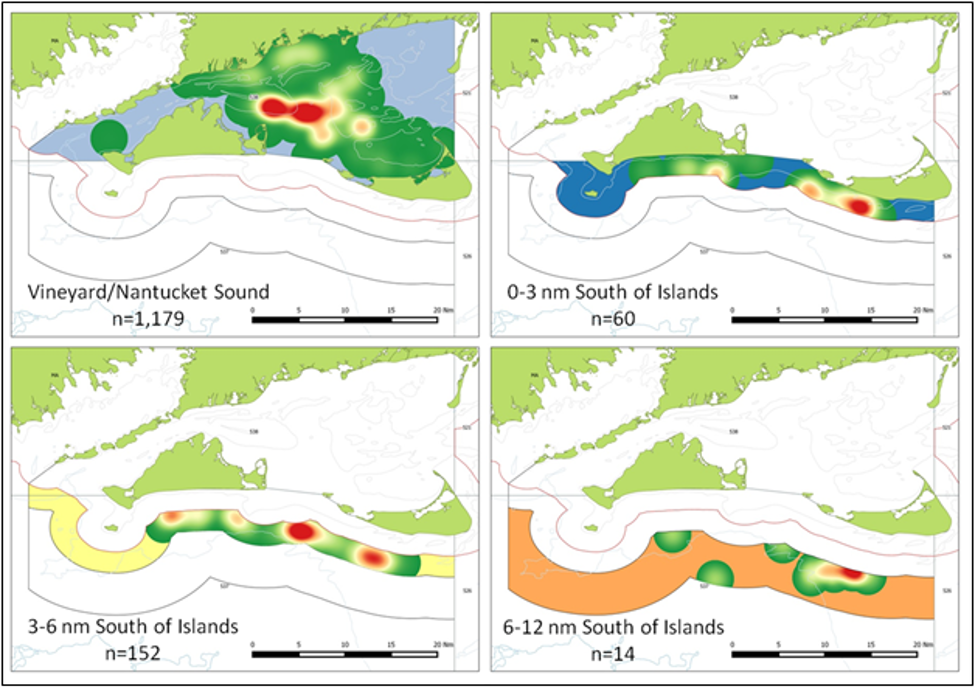

In order to describe and evaluate bycatch and discard levels in this fishery, all observed squid hauls conducted in MA state waters or within 12 nautical miles of Martha’s Vineyard or Nantucket islands were queried from the NOAA Fisheries observer database. When combined with DMF sea sampling, over 1,400 hauls from nearly

200 individual trips were observed in this area during the squid seasons of 2013-2017. Most of these trips (169) and hauls (1,179) came from Vineyard/Nantucket Sound. Sixty hauls from nine trips came from state waters south of Martha’s Vineyard or Nantucket islands, and 166 hauls from 21 trips came from federal waters within 12nm of the islands. This extremely robust dataset allowed for analysis of catch and discard trends, as well as time of year trends, for each distinct area.

The overall discard rate (discarded lb/total catch lb) was 28.6%, which is comparable to other regional small-mesh fisheries, and was fairly consistent between areas. However, annual discard rates were more variable; as high as 54% in 2013 and as low as 8% in 2015. This was likely a result of a smaller available squid biomass in 2013, a theory supported by the low squid catch rates observed in that year (63 lb/hour towing in 2013 vs. 382 lb/hour for all years). Squid catch per hour of towing (i.e., Catch per Unit Effort or “CPUE”) increased as the fishery moved south, likely due in part to larger vessels fishing in the southerly federal waters areas (3-6nm and 6-12nm south of islands).

Other trends were exposed when the catch and discard rates of commercially and recreationally important species were examined by area and year. For example, scup discard rates saw a large increase in 2016 and 2017, as did black sea bass rates in 2014 and 2016. Recent stock assessments for these species revealed all-time high year classes in preceding years which explains the more frequent interactions. Additionally, fluke discards were low in state waters hauls, but increased in federal waters as effort moved south.

Conservation concerns exist in regard to significant squid trawl fishery bycatch species that are overfished (e.g., Atlantic mackerel, winter flounder, bluefish, red hake) or are experiencing overfishing (e.g., Atlantic mackerel, striped bass, red hake, Atlantic cod). Of these, only mackerel, winter flounder and bluefish show catches exceeding one-tenth of one percent of overall catch, but remain below 1% of overall catch. Both mackerel and winter flounder have had stock rebuilding plans initiated and have not exceeded overall quotas in recent years. Mackerel quotas have even been increased in recent years. Striped bass bycatch is low (0.1%) and not concerning in the context of recreational and commercial release mortality. Concerns about removing forage for important predator species are dispelled by studies that suggest striped bass in Nantucket Sound have a varied diet (consisting of 3.3% squid by weight, Nelson et al. 2003) and are adaptable to many prey species.

Finally, longfin squid have been shown to be a biologically resilient species capable of large biomass booms and occasional busts. Spawning throughout the year, these cephalopods create “micro-cohorts” that have various growth rates and migration timings. Squid become mature adults in about 5 months, and live roughly 9 months. In general, offshore spawning in the fall-winter months will create the adult biomass that is harvested in inshore waters during the spring-summer months. Correspondingly, the inshore spring-summer spawning events create the adult biomass fished in offshore waters in the subsequent season. Longfin squid quota is federally managed in trimesters, with paybacks for exceeding the quota coming within the same year. These realities buffer both stock components from overharvest and lasting biological damage.

One aspect of the fishery where biological concerns remain unanswered is the catch and discard of squid egg clusters called “mops”. While no local studies have been conducted, squid eggs reared in laboratory settings have been shown to hatch early when disturbed, leading to incomplete yolk sac absorption (Boletzky and Hanlon 1983). Egg mops were caught and returned to the water on about 15% of observed hauls, occurring in all areas. While the impact this bycatch has on the overall spawning ability of the inshore biomass is unknown, it is believed that multiple mobile-gear closure areas, untowable bottom and fixed-gear presence create a level of refuge that minimizes any negative impacts. However, this topic would benefit from further local research.

The DMF Squid Report paints a picture of a valuable fishing opportunity for vessels that may not otherwise be fishing during the spring season. The fleet of Massachusetts squid boats makes over 20% of their annual income from the month and a half fishery. Groundfish, fluke, scallops, and monkfish make up the majority of remaining incomes.

For more information about the DMF Squid Report, please contact Brad Schondelmeier at brad.schondelmeier@mass.gov or (978) 282-0308 x123. You can also watch the full presentation at: https://www.mass.gov/characterization-of-massachusetts-spring-longfin-squid-trawl-fishery

By Brad Schondelmeier, Fisheries Biologist